Michael King Has Four Pitches and One Earned Run

Michael King is really good. If you’ve been following the Yankees or the American League this season, you probably already knew that. He’s carving hitters up, to the tune of a 0.51 ERA over 17.2 innings so far. He’s striking them out (39.7% strikeout rate) and avoiding walks (4.8% walk rate). He’s doing it in long stints (six of his eight appearances have lasted two or more innings), but he’s excelled in short bursts too.

If you’ve watched King pitch lately, what he’s doing won’t be a surprise to you. His new breaking ball – a slider/curve thing he learned from Corey Kluber last year – is the star of the show. It’s a horizontally-sweeping curveball, or perhaps a slider with unique spin characteristics, or perhaps… look, maybe you should just see one:

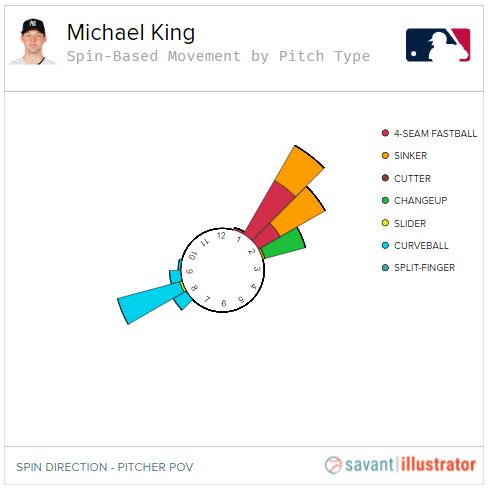

For all the buzz around the sweeper, which the Yankees call a “whirly”, that’s not what King is doing. He’s throwing a curveball – he gets quite a bit of transverse spin on the pitch, which most sliders don’t, and uses Kluber’s curveball grip. Due to his low-slot delivery, however, “downward” break relative to his hand works out to more or less horizontal movement. Take a look at the direction of the spin he imparts on his pitches at release:

The blue lines are what we’re after – for a righty, that’s pure glove-side spin. You can think of it as sidespin. But look at his fastballs – sidespin in the other direction. How does that work? You can try it for yourself at home. Put your arm out straight sideways, then bend your elbow at 90 degrees, so that your hand is up above your head. Imagine an arrow pointing straight down from the bottom of your palm towards your forearm. If you impart spin on the ball that makes it move in the direction of that arrow – downward from the palm – it will break nearly straight downwards.

Next, drop your arm until your elbow is hardly bent. That same downward arrow from your palm would now produce something like pure sidespin – slight downward movement, to be sure, but mostly sideways relative to the ground. That’s what King is doing, more or less – taking a curveball that would be pure 12-6 if he had an over-the-top delivery and throwing it from a low arm slot.

Regardless of how he produces that shape, hitters have been helpless against it. The horizontal break plays well off of his sinker, the fastball he uses more often. The two pitches diverge by nearly two feet horizontally on their path to the plate, which is a lot of real estate to cover.

More than that, King’s usage of his sinker sets up his breaking ball tremendously well. He likes to spot the sinker inside to righties, a natural location given its arm-side run. That’s not a King thing – that’s what almost every right-handed pitcher in baseball likes to do. Righties have located 63% of their sinkers inside of the middle of the plate against righty batters, as compared to only 41% of their four-seamers. A sinker is a naturally arm-side edge pitch.

That’s a perfect complement to a sweeping breaking ball, because the initial flight path of a sinker inside compared with the strong glove-side movement of King’s breaking ball results in something just off the plate away. Expecting a fastball that will jam you and ending up with a pitch you have to reach for results in some uncomfortable, flailing swings:

Sinker/slider relievers are hardly a new development in baseball. King’s sinker has always played well, so pairing that fastball with a breaking ball that mirrors its movement is a no-brainer. But there’s a problem: King’s sinker isn’t an ideal pitch against lefties. The pitch shape he likes most – start it over the middle and run it towards the right-handed batter’s box – is easier to track for left-handed hitters.

What’s more, the Yankees are frequently shifting behind King (more than half the time against lefties over the last two seasons), and throwing a grounder-inducing pitch to the outer edge of the plate results in a pile of opposite-field grounders. An overly-specific way of quantifying that: when a left-handed batter hit a grounder on a fastball from a right-handed pitcher, they pulled the ball 44.6% of the time (2021-22). That’s for all fastballs, regardless of location. When the fastball was on the outer third of the plate, though, they pulled only 24.9% of grounders. In other words, King’s sinker shape is a poor fit for a shift. He’s going to generate grounders, and if he throws the sinker where he likes to, those grounders will be harder to field.

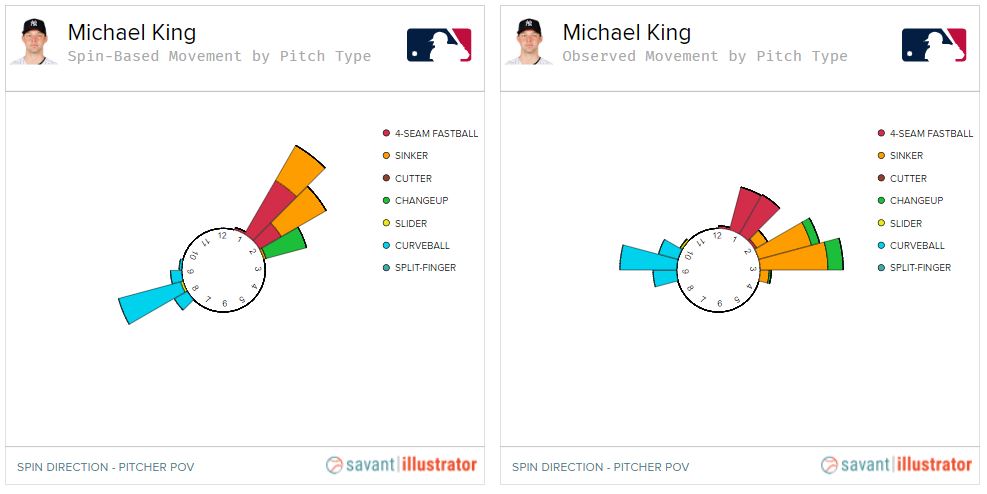

As Grant Washburn of Pitcher List noted, King has an ingenious solution to this: he ditches his sinker and breaking ball. Instead, he relies on his four-seam fastball and a big, horizontally-sweeping changeup. Let’s go back to the Baseball Savant spin charts again, but this time add the observed spin direction, in other words the movement that the ball takes on its way to home plate. That often diverges from the initial angle:

Against righties, King is playing an east/west game, with a speed differential that creates vertical separation to boot. Against lefties, it’s more north/east; his changeup dips and fades off the plate away while his four-seamer rides and hugs the top of the zone. My hangup about pitches away leading to opposite-field grounders isn’t as worrisome with King’s changeup; he rarely throws it in the zone, and if batters do swing, they hardly ever make contact.

That plan has worked well so far this year – to the tune of literally a zero wOBA against lefties – but that’s not enough of a sample to be certain of anything. Throughout his career, he’s struggled against opposite-handed hitting and adjusted his pitch mix in an attempt to cope. This year, the four-seamer is his new innovation. In his career before this year, he threw it to lefties around 12% of the time. This year, he’s at 44%.

It might work! His four-seamer has been spectacular against lefties so far this season. They’re coming up empty on 40% of their swings against it. It’s a fascinating pitch; the combination of his arm slot and delivery give it an extremely shallow approach angle, and there just aren’t many pitchers who throw riding four-seam fastballs from a similar spot. He’s changed the shape of the pitch quite a bit this year – he subtracted nearly two inches of arm-side fade while adding more than an inch of ride. That makes it look even stranger to hitters – the more vertical and the less horizontal movement you can get when you’re releasing the ball from a low arm slot, the more hitters will be fooled. It doesn’t hurt that he sits 95-96 mph with it, either.

In fact, I think a lot of King’s pitches would work well even if he used them more extensively against hitters on both sides of the plate. That four-seamer isn’t some uniquely challenging puzzle for lefties to solve; I suspect it would work well against righties, particularly righties trying to solve the sinker/sweeper puzzle he poses on every pitch. That’s just a hard pitch to hit, for anyone.

Maybe he can’t use the breaking ball quite as often to lefties – even at his peak, Kluber shied away from the pitch when he was at a platoon disadvantage in favor of a cutter – but as a back-foot breaking ball that preys on hitters sitting on his four-seamer, I think it shows promise. King has dabbled with it more of late – he threw three of them in a single at-bat to Kyle Isbel a few days ago, and if he’s as adept at locating it off the plate inside to lefties as he is keeping it low and away to righties, it can function as a put-away pitch when he needs it.

That’s a starter’s arsenal, and King was a starter in the minors. He even took a brief turn in the rotation last year when New York was dealing with a rash of injuries. I suspect the Yankees will give him another chance at a full-time starting job at some point this year; their bullpen is one of the deepest in baseball, and several of their current starters carry injury concerns.

For now, though, King is doing his best fireman impression, appearing when he’s most needed and making innings vanish for the opposition. I don’t think he’ll keep it up to this extent, but I don’t think anyone does – he has a 0.51 ERA, after all. It’s barely May, and the season started late this year. Anyone can do anything for 17 innings. Usually when I write an article like this about a reliever, it comes with a caveat. “Hey, this guy is doing a neat thing, and doing it in a small sample by maxing out on his best pitches, so he might be in for an adjustment.”

But this isn’t some early-season mirage, or at least I don’t think so. King has a ton of plus pitches. He learned Corey Kluber’s breaking ball and has a knack for locating it. He pumps 96 mph fastballs with either plus rise or huge horizontal run. What are hitters supposed to sit on? Every time I look at another pitch he throws, I’m convinced that could be his best pitch. The fun never stops. The Yankees might need pitching less than any other team in baseball – and now they have someone who could be a dominant reliever or a plus starter. Sometimes it’s good to be King.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

I had been patiently awaiting for this breakdown. He’s been so good. I think the Yankees keep him where he is for the time being and go to other options (like Schmidt) in a spot start, unless there is an extended injury in the rotation. I would expect his transition to the rotation to happen next year instead.

I wish more teams would use their young pitchers as long relievers @ MLB level and transition into the rotation over time as endurance, repertoire, etc builds. Else, they transition to back of the pen where a pair of good pitches at max effort can play up.