MLB’s Winning and Losing Efforts to Conquer TV, Part I: The Strike

When massive television dollars from broadcast giants ABC, CBS, and NBC stopped flowing directly into baseball owners’ pockets 25 years ago, the downturn in revenue helped to cause a strike that the sport took years to recover from. In the earlier part of this decade, a similar specter loomed in the form of a cable bubble, the bursting of which threatened to take away the millions that teams receive to broadcast local games on Regional Sports Networks (RSNs) like the Yankees’ YES Network or the Cardinals’ Fox Sports Midwest. Due to a diversification of revenue, an emphasis on developing streaming technology with a impact felt beyond the sport, and an increasing number of bidders, both traditional and non-traditional, that want to broadcast baseball games, Major League Baseball has been able to avoid a bubble similar to the one that severely damaged the sport 25 years ago. But, as exemplified by the recent Sinclair acquisitions of RSNs and the Blue Jays’ decision to remove Canadian access to their games on MLB.TV, a short-sighted approach could undo their victory in the long-term.

First, how we got here.

In 1988, CBS won the right to broadcast Major League Baseball’s marquee events, including the All-Star Game and World Series, beginning in the 1990 season. The network would spend $1.08 billion over the following four years for those games, reportedly beating the offers of rival networks ABC and NBC by as much as $400 million. While the deal was massive in its size, its importance was outweighed by a smaller but more significant deal signed the same year.

One concern with CBS’ new deal was the dramatic decrease in the number of regular season games broadcast nationally, moving from more than 30 games per season down to just 12 beginning in 1990. Commissioner Peter Ueberoth laughed off those concerns, noting teams’ ability to sell local broadcast rights. Around the same time as the CBS deal, the New York Yankees announced one such deal:

The prime example was the recent sale of television rights by the Yankees, who will collect $500 million over a 12-year period from the Madison Square Garden cable network for as many as 150 games a season by 1991. The 12 others are reserved for the national television package, now owned by CBS. The Yankees thereby became the first baseball team to award its local broadcast package entirely to cable television, which could set the pattern for other teams in the future.

At the time of that deal, teams like the Brewers and Indians were making around $3 million for their local broadcast rights; league-wide estimates pegged the average as between $4 million to $5 million per year. Factoring in the first national deal with ESPN for $100 million per year, teams made roughly $14 million per year off of those contracts. Local TV deals accounted for roughly 10% of MLB revenue, while national contracts with CBS and ESPN amounted to roughly one-third of total MLB revenue, with the latter effectively providing the sport with de facto revenue sharing. Today, the local and national television numbers are pretty close to equal at about 15% of MLB revenue each. But that didn’t happen until after the network money bottomed out and helped cause a strike.

Those who warned that CBS would lose a lot of money on baseball in the early 90s were proved correct; CBS lost hundreds of millions on the baseball contract. When it came time to accept bids for a new deal, CBS wasn’t willing to guarantee more than $120 million per year, less than half the prior contract in what would amount to a significant loss in revenue. In the end, MLB went with a shared revenue agreement with ABC and NBC that they hoped would provide $140 million in 1994. With ESPN’s annual commitment dropping to $42 million, MLB revenues were set to drop by more than 10% because there weren’t enough suitors for a national baseball package.

Back in 1991, after the first full year of the new television contracts, major league payrolls jumped by 50% compared to the previous season and continued to rise, more than doubling between 1990 and 1993. Because CBS didn’t want to pay much for baseball after its massive losses, and ABC and NBC didn’t want to pay for baseball after their previous losses, there was nowhere for baseball to go. Fox was still months away from making a billion dollar plunge into the NFL. So MLB did the best it thought it could at the time. Set to see a big loss in revenue in 1994, owners cut back on payroll, leading to failed negotiations over a new Collective Bargaining Agreement followed by a strike and the lockout that carried into 1995.

The strike and lockout actually benefited the owners when it came to television contracts because it meant that advertising targets weren’t met, which allowed MLB to leave the deal and pursue a contract with the now more legitimate Fox network. A combined Fox/NBC deal, along with a new ESPN deal contract $290 million per year from 1996-2000, an increase over the previous disaster, but still significantly less than what the owners made before the strike. The next deal with Fox for $2.5 billion over six years, along with $150 million per year from ESPN, represented regular growth and the first time baseball topped pre-strike television revenues.

Since the strike, the national broadcast deals have continued to grow, with the recent deal with Fox going through 2028 with an average annual value over $700 million and an increase of more than 30% over the current contract. However, even as the national deals have gotten better and better, they have continued to matter less to the financial health of the sport.

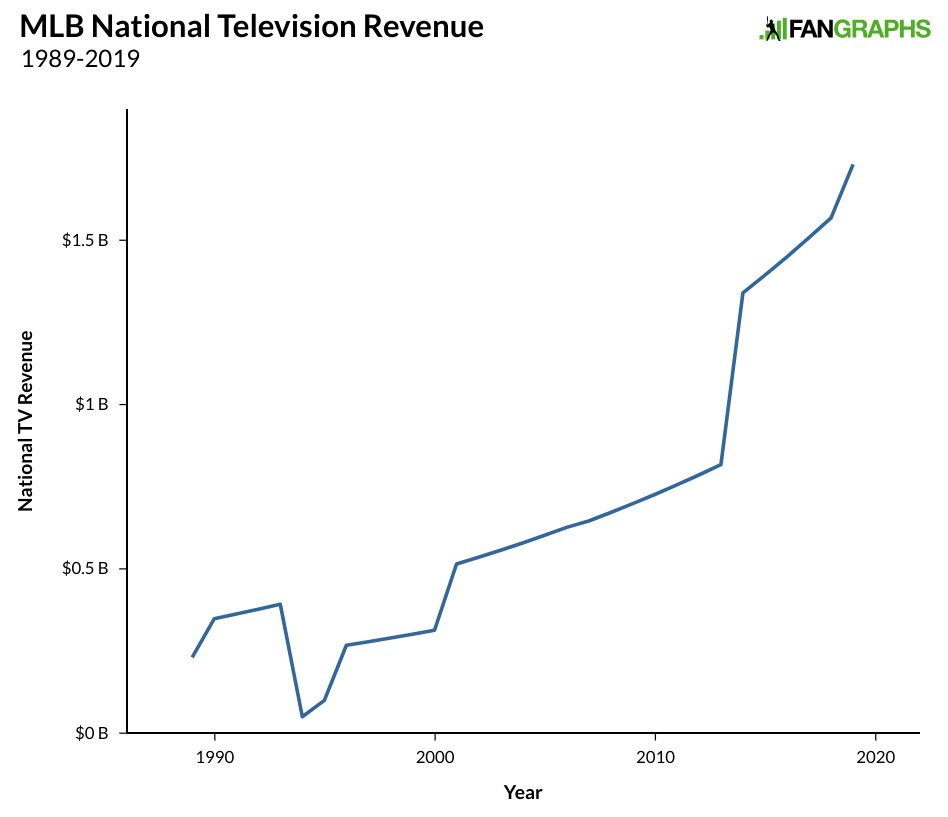

The graph below shows an estimate of the money MLB generated on their national television deals since 1989, with the 1994 and 1995 estimates particularly rough and all long-term deals expected to rise by 4% annually:

We see the dip around the strike and lockout in 1994 and 1995, with the ill-fated Baseball Network followed by a weak deal, before revenues recovered in the last couple decades and growing even bigger the last few years. This money, along with new contracts from DAZN and other MLB activity provides every team with around $90 million.

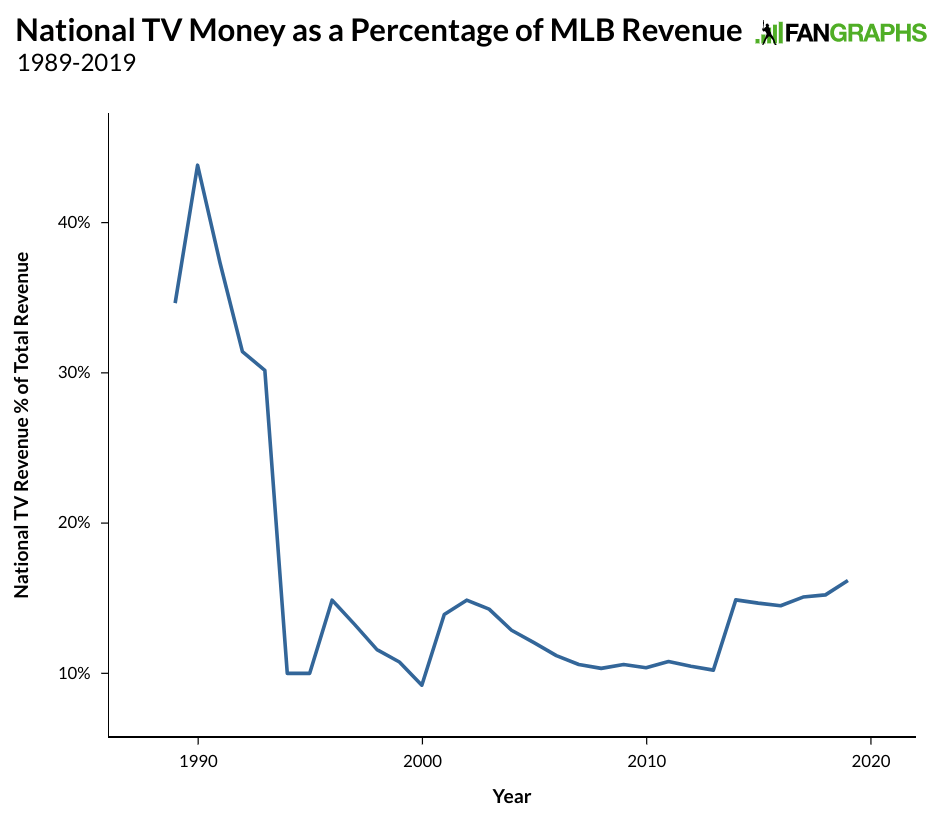

Now, let’s take these national television deals as a percentage of MLB’s total revenue. Estimates for revenue in 1994 and 1995 are rough – just understand that they were terrible. For 1989-1991, the estimate was created based on a percentage of player payroll, with payroll expected somewhere between 55% and 67%. All other revenue estimates are from the now gone bizofbaseball sites operated by Maury Brown and numbers published by Forbes:

The national deals were a huge part of MLB revenue before the strike. For a decade after the strike, they didn’t constitute a terribly high percentage, but that was mainly due to the low value of the deals. As the TV contracts increased far beyond pre-strike measures (even after inflation, the CBS deal brought in only half the money of the current contract), they never got much higher than 15% of total MLB revenue until 2017 and we’ve seen two more raises since then.

Major League Baseball found other ways to increase revenue throughout the 2000s, but recent history has found the sport slightly more reliant on those big television contracts. With the current CBA expiring at the same time as deals with ESPN and Turner Sports, MLB has gotten itself in a bit of a pickle, hence the ridiculous playoff proposal meant to eke out more money in those negotiations. The diversification that has helped an explosion in MLB revenues (which caused less reliance on big television contracts) has been very good for business, but attempts to further increase revenues at the same clip could cause vulnerabilities in the long-term. Up next, we’ll explore how MLB diversified its revenues and where its vulnerabilities lie.

Craig Edwards can be found on twitter @craigjedwards.

Craig, fantastic article! I didn’t know that the expiration of CBS’ very generous deal and the overspending on players that it caused was the cause of the 1994 strike/lockout. Maybe the coming expirations of the ESPN & Turner deals contributed to team reticence to sign FA’s in the 2017 & 2018 off-seasons and thus drive the MLBPA share of league revenues below 50%. (I’d still say most of the reticence was due to weak FA classes and reluctance to give long-term contracts to 30+ yo’s.)

This is really nice work.

I think we’re gonna get into it in part two, but the RSN apocalypse is coming. Comcast is just refusing to carry them in some markets (woo Denver, who kicked altitude to the curb and barring something crazy will do the same with the Rockies RSN) and others are at least talking about doing the same.

It’s not really a refusal to carry an RSN, it’s a refusal to carry the RSN in a basic tier. In short, the RSN’s business model had been built around revenue from cable customers who have no interest in the RSN, thus making the RSN monthly price appear to be a bargain to the customer who DO want to watch the RSN.

It’s going on right now in Chicago where the Cubs’ RSN is having difficulty getting carried on any of the larger platforms. And it’s almost comical how the RSN’s – the Cubs’ Crane Kenney in particular – go out of their way to avoid honestly telling people what the RSN business model is.

Comcast is refusing to carry Altitude in any tier (DISH is the same). DISH is playing hardball with a lot of sports providers right now, weirdly enough.

From what I know, Comcast (et al) would carry Altitude if the RSN would accept being sold as a premium channel (a la HBO). Otherwise it’s about how much of a monthly charge Altitude expects Comcast to pass on to customers in any tier, and how much Comcast thinks they can charge without customers dropping to a lower tier or dropping TV service entirely. The RSN’s are betting the platforms will blink first, but I think they’re going to lose that bet in the long run.

KSE makes this hard to figure out too. It’s assholes all the way down. I mean, the thing is, I can get all of KSE’s offerings online with league pass or…… whatever it is MLS does (ESPN plus).

Now there’s a huge lawsuit. I don’t mind the rockies, but I don’t know how they’re going to keep their RSN on tv unless they take a huge hit to fees.

Ultimately RSN’s are going to have to accept lower fees to get on the low tiers, but more likely they will get pushed (back) to operating as a premium channel. When that happens, they’re going to either lose casual fans (over time) or they will have to get a couple dozen free games on TV somehow.

I am curious what Sinclair does with ATSC 3.0 and if they use RSN’s to draw interest. Chicago’s RSN began as an over-the-air PayTV (scrambled) premium channel before cable TV expanded like crazy, and they would offer an occasional free (unscrambled) broadcast. What’s old may be new again.

Yeah, DISH is still blocking Fox Sports Midwest here in St. Louis as well.

Marquee is on Direct TV ( a large platform) as well many smaller cable systems. The key platform that is a holdout is Comcast. Both sides indicate they will strike a deal by Opening Day, but I’m not so sure.

Also, is it Crane Kenney’s responsibility to educate consumers on how RSNs work? Don’t consumers have a responsibility to educate themselves?

Just echoing that I also had no idea about the relation of those TV contracts to the ’94 players’ strike, which was devastating to me as a young baseball fan. Very much looking forward to your follow up article(s).