Nicky Lopez, Caught Red-Handed

In the 1980s, the stolen base was king. Rickey Henderson and Vince Coleman were absolute terrors on the basepaths, giving pitchers no time to breathe. They each stole 100 or more bases three different times, with Henderson’s 130-steal season standing atop the single-season leaderboard, unlikely to ever be matched. They were hardly the only speedsters, either; Tim Raines stole at least 70 bases in six straight seasons, for example.

That need for speed made a delicious baserunning omelet, but it also cracked its fair share of eggs. In 1980 alone, players were caught stealing 1,602 times. That’s the cost of doing business when you’re going to steal so frequently. If you only attempt to swipe a bag in the 50 best spots to run in a given year, you’ll be successful at a higher rate than if you go 150 times.

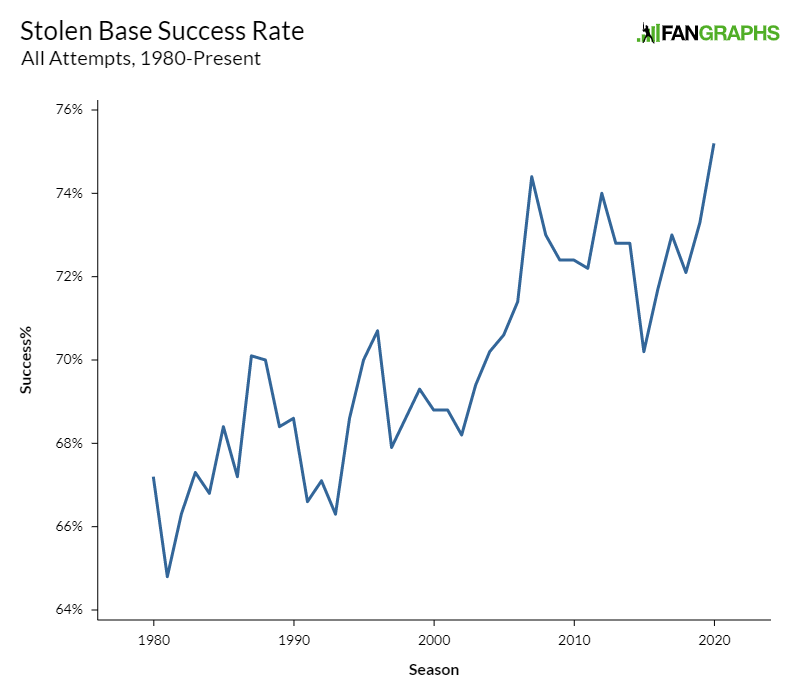

As baseball tactics changed, the steal lost favor. First, home runs decreased the value of steals. Put one over the fence, and it doesn’t matter which base the runner was on. Second, teams started to better understand the value of avoiding outs. The exact math varies based on context, but as a rule of thumb, you need to steal three bases for every time you’re caught to provide neutral value. Succeed less than 75% of the time, and you’re costing your team runs in expectation.

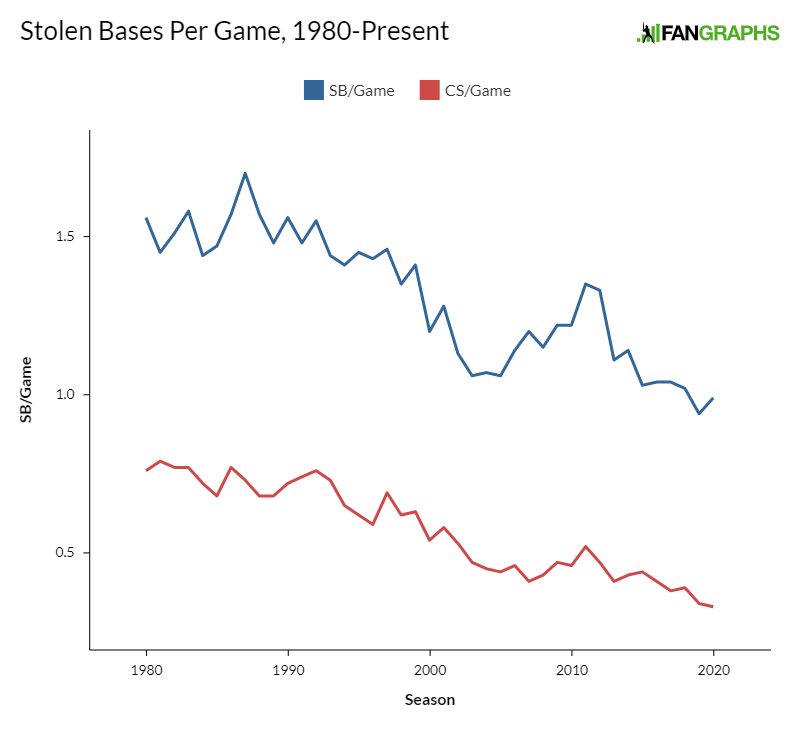

These two effects led to a predictable change in behavior. Stolen bases have been in steady decline, while success rate on the attempts that remain heads inexorably higher. In 1980, the average game featured roughly 1.5 steals, and the league-wide stolen base success rate was 67%. In 2020, there was less than one steal per game for the second straight season:

On the other hand, the success rate crested 75% for the first time:

Is this a good development? It all depends on your point of view. Steals are exciting, whether they’re successful or not; they punctuate the stilted and ponderous pace of the game with a jolt of pure adrenaline. On the other hand, there’s nothing more frustrating than seeing your team run themselves out of an inning or seeing a baserunner caught directly before a home run.

Luckily, those vibe-killing outs happen far less frequently these days. A rising success rate and decreasing attempt rate both lower times caught stealing, which means the number of unsuccessful steals per game has plummeted even more.

Yes, the modern game is littered with efficient base-stealers. Mike Trout has a sterling 84.4% success rate, comfortably ahead of Henderson’s 80.8% and Coleman’s 80.9%. In the 11 years from 2010 to 2020, a whopping 23 players stole 100 bases with a success rate above 80%. Only 15 players could say the same from 1980 to 1990, despite all the emphasis on speed. Trout and Mookie Betts both have a shot at retiring as the most efficient base-stealers of all time.

That doesn’t mean modern players are better at the act of stealing than the 80s speed demons, merely that they’re more judicious in their attempts. Lefty on the mound? No feel for the pitcher’s pickoff move? Might as well stay put. Those marginal steal attempts were never great plays, anyway.

Don’t tell any of what I just said to Royals second baseman Nicky Lopez. Before this year, he seemed like the same diffident kind of baserunner I’ve been describing. In 2018, he stole 15 bases while being caught six times, close to breaking even. He started off slightly better in 2019 — he went 9-for-12 on steal attempts in a brief minor league stint. Then he made the major leagues and jammed on the brakes; in 402 plate appearances, he attempted only two steals.

Essentially, that’s playing the percentages. He wasn’t an overwhelming stolen base threat in the minors, and major league catchers and fielders are better than their junior varsity counterparts; stealing more would have been counterproductive. The cold, hard math says that for someone like Lopez, discretion should be the better part of valor. It’s better to attempt no steals at all than to run yourself into a pile of outs.

That was the backdrop going into 2020: Lopez was an inexperienced and infrequent base-stealer, and there’s nothing at all wrong with that. He could simply sit back and wait for the best times to go for it. A high-leverage run with two outs against a fancy-delivery reliever? That sounds great, and he found that spot in only the second game of the year:

James Karinchak is absolutely the kind of guy you want to steal on. He’s slow to the plate, he’s more likely than your average pitcher to bounce one, and stringing two hits together against him is essentially impossible. Getting to second turns any hit into a run, which is a huge upgrade. Bad outcome, but good process!

You can’t win them all, and that one wasn’t such a bad one to lose. This is exactly what I mean by picking your spots around steals. For the next two weeks, Lopez played it close to the vest — no steal attempts. Teams still treated him as a threat to steal, because he’s fast and the Royals run a lot. On August 8, Lopez decided he’d seen enough. After Mitch Garver bluffed a back-pick and Jake Odorizzi threw over twice, it was time to hit the gas:

Hoo boy. That’s about as poor an attempt as you’ll see without someone falling down. His best chance might actually have been retreating after he got off so poorly, but you don’t often see someone come up so short that their slide doesn’t reach the base. Two attempts, two times caught; maybe it was time to cool it with the steals.

Yeah, about that. The next day, Lopez got another shot. With the Royals leading 4-2 in the bottom of the 8th, Lopez drew a one-out walk. The Twins were on guard; Cory Gearrin threw over to check on him before he threw his first pitch to Cam Gallagher. That’s all he needed to see; it was time for another high-stakes heist:

Not great! That little stumble out of the blocks proved decisive, and you never want to be so obviously out on a steal that you pop up from your slide and immediately run back to the dugout looking like this:

At this point, there was no salvaging an efficient year on the basepaths. Just to break even, Lopez would need to steal nine bases in a row without getting caught, and time was ticking away on the season. More realistically, it was time to stop attempting so many steals. He was out by a mile on the last two of those. Reaching base is great! Maybe just stand there for a while, you know?

For the better part of three weeks, Lopez just stood there. It was station-to-station time, and hey, at 0-for-3 on steals, there’s nothing wrong with that. You can only keep the demons asleep for so long, however, and Lopez clearly itches to run. On August 28, he drew a leadoff walk in the top of the fourth inning. Leadoff baserunners are incredibly valuable, and in a one-run game, they’re even more dear. Great work, Nicky! And then, well:

In theory, Lopez is too fast to get thrown out on a one-hopper that Yasmani Grandal released from his knees. In practice, the combination of a bad jump and an intervening foot did him in again. Strike ‘em out, throw ‘em out, do not pass go, do not collect $200. The Royals came up empty in the inning and eventually lost the game by a run.

If I got caught stealing four times in a row to start a campaign, I wouldn’t go for a fifth. It’s self-preservation more than anything else. I’m not a professional athlete, however, and you probably can’t get far in baseball without overarching confidence in yourself. Lopez was right back on the horse two weeks later. He led off the third inning of a tied game by singling into center — yet again, a valuable leadoff runner. Stop me if you’ve seen this one before:

It’s a closer play, no doubt — without a perfect tag there, he would have been safe. Francisco Lindor made a great tag though, and it was time to pull a sad Charlie Brown walk back to the dugout:

This, mercifully, was his last attempt of the year. He finished 0-for-5 on steals, a perfectly futile season. We may never know if the team gave him a red light, but they would have been well within their rights. He essentially turned five hits into outs, doing the defense’s job for them.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this isn’t the first time a player has recorded a “perfect” zero stolen base with a pile of caught stealings. Lopez is only tied for the fourth-most times caught stealing without a successful steal since 2000:

| Player | Season | SB | CS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jose Offerman | 2000 | 0 | 8 |

| Oscar Robles | 2005 | 0 | 8 |

| Aubrey Huff | 2009 | 0 | 6 |

| Albert Belle | 2000 | 0 | 5 |

| Todd Walker | 2001 | 0 | 5 |

| Nick Hundley | 2010 | 0 | 5 |

| Nicky Lopez | 2020 | 0 | 5 |

It felt, for a while, like the days of aggressive and inept base-stealers might be over. No one been caught five times without a successful steal since 2010, and that’s hardly a surprise; Albert Belle and Todd Walker aren’t known for being particularly fleet of foot. It was mostly people who weren’t as fast as they thought they were, the kind of inefficient steal attempts that have been squeezed out of the game in the last 20 years.

Next year, Lopez might reclaim his successful base-stealing form from the minors. I can flat guarantee you that he knows he had a poor year on the basepaths, because you simply can’t be that bad and not realize it. Whether he does or not, however, he likely won’t match this year’s futility. These perfect shutouts are getting less and less common over the years, even if the occasional brutal baserunning season still happens.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Love this! There is something to be said about steals just being *fun.* Is there a way to encourage them again without unbalancing the game? Like, what if, when you steal second, you get to put a runner on first? OK, that makes it *too* valuable — but you see what I mean.

Also: Francisco Lindor make a great tag though –> Francisco Lindor made a great tag though or Francisco Lindor did make a great tag though

Fixed, and my vote would be for bases that were slightly closer together, because I also love a good steal.

Moving the mound back or requiring the catcher to maintain a certain minimum distance behind the plate would have a similar effect without the need to alter the dimensions of the infield. Additionally, making the bases slightly closer together would also reduce the distance that the catcher is required to throw the ball.

I wonder if they ever will be forced to move the mound back. With the advances in technology, it seems that in the last few years every single pitcher is adding velocity. I could imagine, without rule changes that K % continues to increase and increase year over year. You would think that if changes continue, eventually a change will have to be made. Some people think that moving the mound back would be tougher on hitters since pitches would move more, but I disagree. More reaction time is most clearly the most important thing. Not saying I want to move the mound back, but do we really want a league where people are striking out 30% of the time?

I wonder how much of that K% issue is really on the hitters (I think a lot of it). Hit the ball hard; it’s okay to K, etc.. “Chicks dig the longball!” 😉

Maybe a lot of it. But every twitter video is of some unsigned free agent working out in Washington throwing 101 mph. Reaction time I feel is a big thing, and the amount of guys hitting 100 is increasing. It wasn’t that long ago that basically no one hit 100, now multiple pitchers hit 100 every game.

IMO moving the rubber back two feet would have a dramatically negative effect on pitchers, who already struggle to stay healthy. If the rubber were to be moved back, try one foot and do this experiment at some level below mlb.

Two feet, raise the mound back to 1968, when injuries were far fewer and starters threw 300 innings.

If you get a steal, the current batter gets a ball added to the count.

My idea was that 3 unsuccessful pick off attempts counts as a balk. It incentivizes the players to take bigger leads, it incentivizes the pitchers to not waste pick off attempts. Plus it makes the pick off move actually interesting from a strategic perspective.

Oooh I like this one too.

@MLB Commissioner’s Office

You could increase the relative value of steals by moving the fences back. Fewer homers and more singles would increase the benefit you’d gain by going from first to second. Also, you’d have more triples, which are another one of the funniest plays in baseball.