Omar Narváez Puts it All Together

Who’s the best catcher in the NL Central? Before the season, this was a good way to start an argument between Cardinals and Cubs fans. Was it Willson Contreras, the cannon-armed, cannon-batted Chicago backstop who has worked hard to improve his framing of late? Was it Yadier Molina, the stalwart St. Louis lifer with legendary defense who continued to hit long past when most thought he’d fade?

Neither! The best catcher in the NL Central this year is Omar Narváez, and it hasn’t been particularly close. By WAR, his 3.0 mark is nearly double Contreras, and that undersells it; he’s played in nine fewer games and has 64 fewer plate appearances. His 137 wRC+ is the second-best among catchers, trailing only Buster Posey’s incandescent season. He’s sixth in baseball in framing runs and third in total defensive value for catchers. A year after his worst offensive season, he’s turned it all around, and the Brewers are reaping the rewards.

Narváez came to Milwaukee with a reputation as a defensive butcher who could hit. He popped 22 homers in 2019 in only 482 plate appearances, his lone season in Seattle. Not only that, but he also struck out only 19.1% of the time — with a walk rate of nearly 10%. More walks than average, fewer strikeouts than average, plus power … he sounded like a match made in heaven.

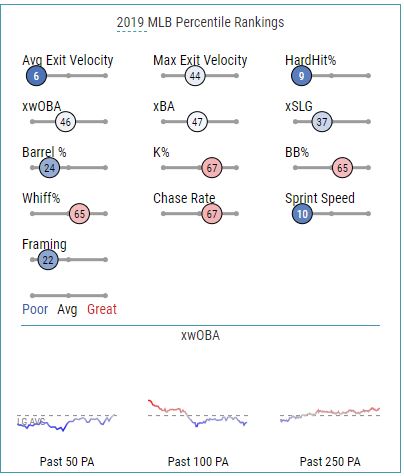

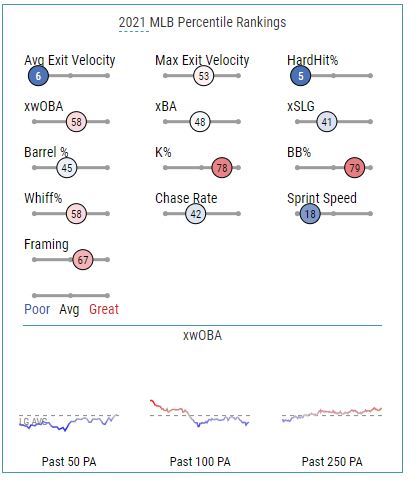

But Narváez’s power has always been a hard-to-quantify commodity. Even in that powerful 2019 season, he put up uninspiring raw power numbers. Take a look at his percentile rankings as compiled by Baseball Savant:

Sixth percentile exit velocity? Ninth percentile hard hit rate? Twenty-fourth percentile barrel rate? That doesn’t sound like a power hitter, and nothing that Narváez did in his abbreviated 2020 — a .269 slugging percentage and two homers — made the numbers seem more real. How did he get back to his power-outcome ways?

If you’re guessing that he improved his raw power output, think again. Here are those same percentile rankings, this time for 2021:

Yup, he’s still substantially below average when it comes to exit velocity and hard hit rate. He’s also slugging .469, with eight bombs and a .300 batting average. So yes, this article will be about Omar Narváez. But it will also be about how average exit velocity and even hard-hit rate can mislead you about a player’s offensive output.

What is average exit velocity? It’s about as straightforward as it gets. Take all the fair batted balls a player hits, add up the exit velocities, and divide by the number of batted balls. Boom, you have average exit velocity. The names you’d expect are where you’d think they are; Giancarlo Stanton leads the league and Jarrod Dyson is in last.

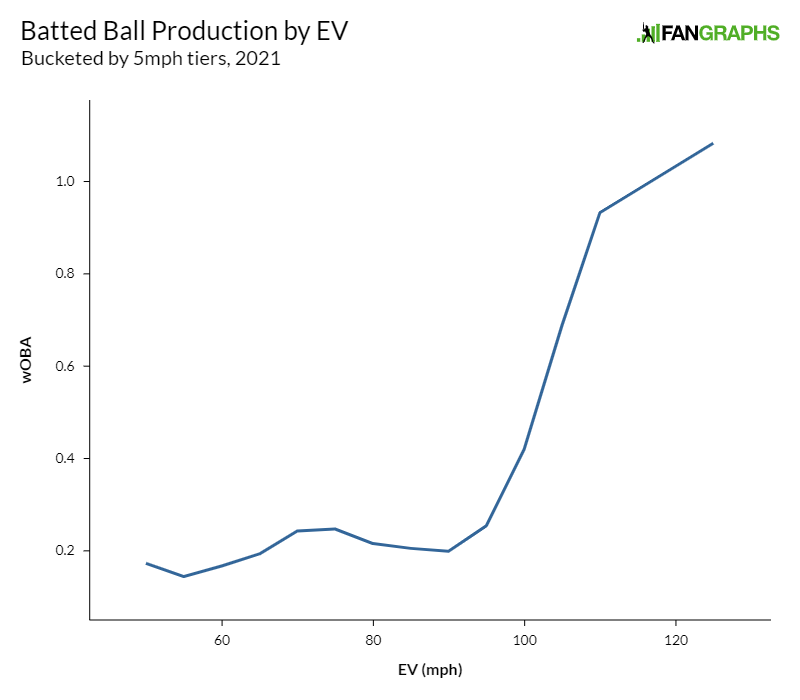

That obscures a big problem with this statistic: namely, that averages are kind of stupid when used in this context. Think of a player who hits a crappy 50 mph pop-up and then a majestic 110 mph home run. That’s an 80 mph average exit velocity, basically Dyson’s 2021 mark. Now imagine he hit that same crappy pop-up at 80 mph. Now that’s a 95 mph average exit velocity, which looks a lot like Stanton’s 2021. But batted balls with 50 mph and 80 mph exit velocity are worth roughly the same on average (roughly is doing a lot of work in this sentence). Here’s roughly how it looks so far this year:

Hit the ball over 100 mph, win a prize. Everything else is just noise, though there’s a fun band in the 70s where soft line drives and fly balls tend to land in front of outfielders. Average exit velocity just throws all of this in a blender, and that clearly won’t work. Look at that line and you’ll see why.

Narváez’s average exit velocity is no big deal. He can dink and dunk all he wants as long as he has some juice at the top end. But, uh, take a look at those percentile charts again. He’s also below average when it comes to hard-hit rate, and that doesn’t sound good. Hard-hit rate ignores the bottom of the scale, so it doesn’t suffer from the same problems we’ve just discussed.

Can I make that seem less relevant? I can at least try! Statcast hard-hit rate considers batted balls to be anything hit 95 mph or harder, and while that’s not a perfect match for our graph, it does a pretty good job of it. Again, using a blanket definition obscures what’s going on, though in a different way.

First, I’m going to make a slight change in definition. Statcast uses 95 mph as a cutoff, but I’m going to use an even 100, because that’s where the values really start to tick up. Let’s look at those batted balls. The average wOBA on those batted balls is .774, which is downright great. But hey:

| Batted Ball Type | wOBA |

|---|---|

| Grounder | .363 |

| Line Drive | .807 |

| Fly Ball/Pop-up | 1.293 |

Ground is bad. Air is good. When you’re hitting the ball this hard, it’s as simple as that. Narváez is a fly ball hitter, which means that when he hits it hard, it usually goes somewhere useful. Think of it this way: He’s in the eighth percentile when it comes to the rate at which he hits batted balls 100 mph or harder, which is quite close to his fifth-percentile hard-hit rate.

That’s not the relevant question. What we want to know is how often he does good things, like putting the ball in the air when he hits it hard. There, he’s better; he’s in the 20th percentile of all players. That’s hardly elite, but it’s a far sight better than eighth.

You might realize that I’m getting closer and closer to barrel rate as I refine my definition. Barrels are a different subset of hard-hit balls; they’re hit very hard and at very dangerous angles, such that their average result is extremely positive. You can read up on the official definition here, or see Alex Chamberlain’s delightful slicing of barrels here.

All this is to say, Narváez does even better by barrels. He’s in the middle of the pack there, and that’s probably a good guess at his true talent when it comes to batted ball quality — not great, but not bad. He gets to it in a strange way, as he’s in the worst 35% of baseball when it comes to batted balls hit below 70 mph — a list that is almost all slap hitters. But despite those mishits, his good contact quality is quite solid; when he hits it square, he mostly puts it in the air.

That means that most of his success will ride on his ability to avoid strikeouts and take walks, and that’s been his true step forward this year. In his first year in Milwaukee, no one cared about his contact quality because he simply wasn’t making any contact. He struck out 31% of the time, a rate that you’d need Stanton-level power to overcome. As we’ve established, he’s not a weakling, but he’s certainly not Stanton, and the overall package simply didn’t play.

What was his problem? He started chasing more — a lot more. Batters miss far more batted balls when they swing outside the strike zone, obviously enough. Narváez’s swing rate didn’t budge much between 2019 and ’20, but his judgment of the strike zone did:

| Rate | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| Swing% | 47.7% | 48.8% |

| Heart Swing% | 77.2% | 75.6% |

| Shadow Swing% | 54.9% | 53.2% |

| Chase Swing% | 19.4% | 28.5% |

| Waste Swing% | 3.1% | 9.8% |

If you swing at more chase and waste pitches, you’re going to miss a lot more, and that’s exactly what happened. You could theoretically make up for that by being more aggressive in the strike zone and ending at-bats early, but that’s not what happened; he kept his normal tendencies on good pitches and swung out of his shoes at bad ones. I’m not sure he would have struck out 31% of the time in a larger sample, but his 13.2% swinging-strike rate was a bad look for someone with only average power on contact.

Normally I’d say that this is just something I can’t analyze, but this time I think I have a culprit. Take a look at Narváez’s chase rate when ahead and behind in the count:

| Year | Ahead Chase% | Behind Chase% |

|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 22.4% | 20.6% |

| 2018 | 21.8% | 22.2% |

| 2019 | 27.5% | 29.2% |

| 2020 | 32.6% | 43.0% |

| 2021 | 29.5% | 29.0% |

His behavior didn’t change much when he was ahead. The second he was behind in the count, he expanded the zone, and pitchers were only too happy to toss him junk and watch him flail. As you can see from the 2021 numbers, however, he made a change this offseason, and he seems to be back to his earlier ability to hold off when down in the count. It’s come more or less without cost, too, as he’s swinging more at pitches in the zone when he’s behind. Last year now looks like an aberration; his pitch recognition went haywire, and everything fell down around it.

It’s reductive to say that that’s the only thing Narváez has changed, but I’m okay with being reductive. He always looked like he had acceptable offensive chops, and the book had always been that if he could clean up his receiving, he’d be a solid backstop for years to come. He managed that in 2020, but those acceptable offensive chops vanished simultaneously.

Now that they’ve returned — and now that he’s seemingly carried over his improved receiving — Narváez is a deserving All Star. He probably won’t keep hitting quite this well, but he doesn’t have to. Now that he’s cured his strikeout woes, he can go back to his weirdo, soft-hitting but still powerful ways — the ones that made him a solid hitter. It might not look pretty, and it might not look normal, but Narváez has finally put everything together.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

His is a distinctively uppercut swing so it’s not surprising Narvaez lives in the air. But how he manages to avoid striking out on high heat ad nauseum with such an approach is a delightful, if mysterious, skill.