Pitch Design: Let’s Add Some Depth to a Curveball

Curveballs can be fairly vexing to classify. Though not as vast as the kingdom of sliders, curveballs have more personality than other pitch types. Some curveballs have heavy sweep like a slider (slurve), or have a grip variation that will kill spin (knuckle curve); others can fall like a hard changeup (churve), while another variant seems to float in slow motion on the way to home (eephus).

Most tend to fit the more stereotypical slicing shape (sweep with comparable drop), or have a heavy arch that fits the 12-6 style. Each variation has its own identity and benefits depending on factors such as arm slot, spin direction, and axis orientation.

There are situations where a pitcher adopts a particular style but fails to execute the pitch, so it fits into its sub-category. You can have a 12-6 curveball that plots normally on the x-axis but fails to drop far enough down the y-axis. Or, you can have a more classic curveball that doesn’t separate itself enough from either plot point, which causes the pitch to hang in the zone.

But we can make adjustments to these undesirable results, and that’s what we’ll be focusing on in this piece. What can be done to add depth to a curveball that regularly demonstrates a lack of life or separation from the center of the pitch zone chart?

There are essentially three categories of curveballs that generalize the pitch’s behavior: The “classic” curveball, which shapes with equal parts sweep and depth, the “slurve,” which has more sweep than drop (more horizontal than vertical break), and the “downer,” which is basically a 12-6 curve.

The classic curveball is generally thrown with tilted topspin under a spin direction of 4:30 (or 315 degrees) for a lefty, and 7:30 (or 45 degrees) for a righty. It comes mostly from pitchers that throw from a 3/4 arm slot”

The slurve (which sometimes fits into the slider category), is mostly thrown with a heavier gyro component (lower spin efficiency) at about 4:00 (or 300 degrees) for a lefty and 8:00 (or 60 degrees) for a righty. This style comes from side armers and some lowered 3/4 arm slots, but it can be produced at other slots as well, depending on the gyro orientation of the pitch.

For example, if you have a higher arm slot, you’d have to pull down on the side of the ball much more than the back end to produce the desired slurve shape. When it comes to depth, slurves get most of theirs from gravity due to lack of the Magnus effect:

Then we have the downer, or 12-6 curveball. This is the heavy topspin variation thrown mostly by over the top arm slot pitchers. Thrown around 5:00 (or 330 degrees) for lefties and 7:00 (or 30 degrees) for righties, it acts as its name suggests: a somewhat straight or arching path to the plate with a large amount of vertical break.

To begin my assessment, I looked at all the PITCHf/x data for pitchers who threw at least 60 innings in 2019 and used their curve (knuckle or traditional) at least 20% of the time. Next, I came up with a rudimentary “depth” figure (tMov) by adding horizontal and vertical break together, much like the “Movement” data in our splits category. Then, I compared the data to the league-average PITCHf/x movement figures to get a frame of reference to compare to.

| Handedness | hMov | vMov | tMov |

|---|---|---|---|

| RHP | 4.5 | -5.1 | 9.6 |

| LHP | -4.6 | -5.2 | 9.8 |

With that data, I came up with an average curveball movement total (tMov) of 9.7. This fits best with the classic curveball profile, which makes sense since it’s the most common style thrown.

Now, for my example, I’m specifically looking for is a pitch with minimal horizontal and vertical break. We would not suggest alterations for a pitcher like Tyler Glasnow, who has below average sweep but a tremendous amount of drop, or someone like José Berríos, who has heavy sweep but below average drop; they don’t really need any adjustments to their depth.

After running my query, I found these five pitchers who lack significant sweep as well as drop on their curveball:

| Pitcher | Usage | hMov | vMov | tMov | pVal | wOBA | SwStr% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrew Heaney | 27% | -2.8 | -2.2 | 5.0 | -3.6 | .299 | 19.3% |

| Zack Godley* | 42% | 1.4 | 3.0 | 4.5 | 2.5 | .305 | 15.0% |

| Drew Smyly | 29% | 2.7 | -0.5 | 3.2 | -4.3 | .294 | 15.8% |

| Domingo Germán | 36% | 0.2 | -2.4 | 2.6 | 5.6 | .266 | 20.2% |

| Alex Young | 21% | -0.5 | -1.7 | 2.2 | 6.9 | .126 | 18.8% |

Alex Young and Domingo Germán show the least amount of depth by a pretty decent margin. However, they get good results from the pitch, which may be due to how they deploy it and the way it fits into their arsenal and overall sequence strategy. Despite a perceived poor movement profile, the fact that the pitch is producing results means little to no tinkering is necessary.

On the flip side, we have two pretty poor curveballs from lefties Andrew Heaney and Drew Smyly. They both also have higher than average curveball wOBAs against.

To keep things from getting too convoluted, we’ll focus on Heaney’s curve; he’s the best candidate to add overall depth since he’s lacking in both sweep and drop. I’m removing the context of the relationship between Heaney’s curveball and the rest of his arsenal, and keying in on just adding depth to the pitch.

For a better understanding of Heaney’s curveball in relation to the average pitch in his slurve subcategory, here’s a look at the contrast between them using the Driveline EDGE tool. Heaney throws more of a slurve (Pitch 2) with a 4:00 average spin direction under a 67-degree gyro tilt (or 40% spin efficiency):

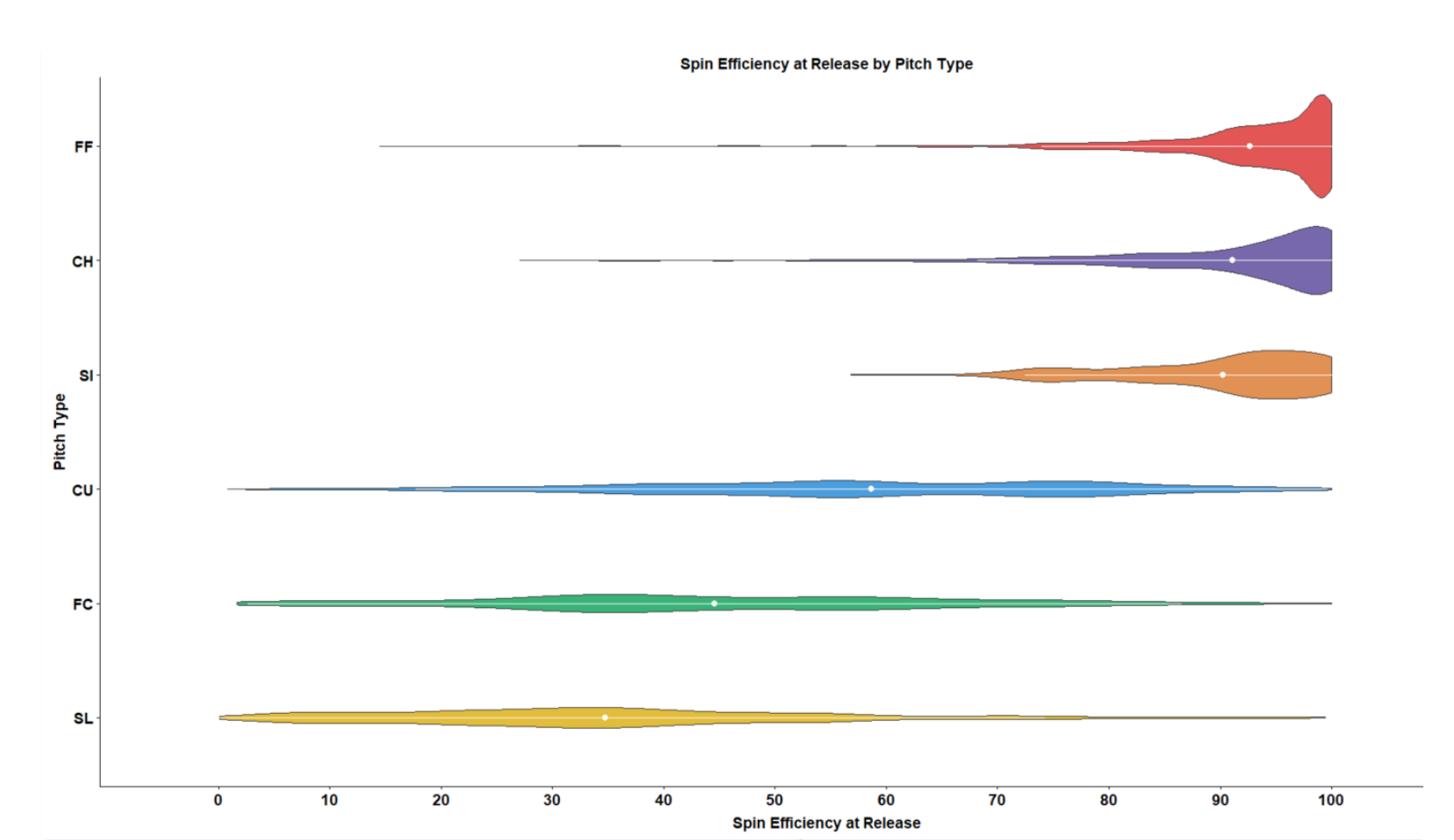

As demonstrated in the above curveball movement chart and the pitch movement clip, Heaney has a high-level of gyro tilt on his curve, which lowers spin efficiency quite a bit. Low efficiency on breaking balls is not always a bad thing, and curveballs tend to have the largest variance of any pitch, but according to the following chart (via Driveline Baseball), Heaney is something of an outlier compared to other curveball pitchers:

It’s worth mentioning that, based on research by Driveline, with the heavy gyro tilt, there is a small amount of spin efficiency that may be added to the curve late in flight (known as “Magnus shift”), which could possibly be limiting the amount of depth Heaney is able to get. According to the efficiency chart above, Heaney could be gaining an additional 6-7% efficiency during flight. (While it still bears mentioning, there is limited research on this phenomenon, so we won’t go off on this tangent.)

So what do we do at this point? The spin direction of the pitch might need to be altered to “encourage” more topspin. Pushing the direction closer to 4:30 is desirable, as that profiles closer to the classic curveball shape that has the extra depth we are looking for. It’s not an unreasonable suggestion as the 30-minute change in direction amounts to about a 15-degree change (from 300-degrees to 315-degrees).

According to Driveline, offspeed pitches can be adjusted by as much as 100 minutes (or 50-degrees); changes that drastic will likely require an arm slot adjustment and you’d have to weigh the consequences of that change while taking into account the impact on the rest of their arsenal.

In Heaney’s case, an arm slot adjustment wouldn’t be necessary; the standard deviation of spin direction on curveballs within a specific arm slot is just over 17-degrees:

| Pitch Type | Standard Deviation of Degrees |

|---|---|

| Changeup | 15.0 |

| Curveball | 17.2 |

| Cutter | 26.4 |

| Four-seam | 11.5 |

| Sinker/Two-Seam | 11.4 |

| Slider | 39.0 |

There are some things that Heaney can do to eliminate the heavy gyro that’s killing any additional depth he might otherwise get. We want to focus on getting more topspin while still allowing some room for bullet spin and sidespin. Heaney could very well be pulling down on the side of the ball instead of getting over the top of it.

Ideally, at this point, we would utilize high-speed video to suss out any problems with grip and/or wrist orientation at release. If we had access to video and were able to diagnose any aforementioned issues, how Heaney is gripping the ball could help us determine if he’s leveraging the seam enough. That’s important; doing so will help create the additional desired topspin to turn the pitch into more of a classic curve rather than the slurve-ish shape he currently induces. We could also check to see if Heaney is placing his fingers between the seams as opposed to across them, which makes it more difficult to create topspin. After working with an adjusted grip, another option for Heaney is to add a spiked grip to the pitch, as seen in the picture below:

In this photo, we can see how this alternate grip forces the middle finger to apply the necessary additional pressure on the ball for improved control over the direction of spin while helping the pitcher pull down on the pitch more from the top instead of the side of the ball (which creates additional bullet spin we want to avoid).

Additionally, providing mental cues is important. They help a pitcher visualize what they need to be thinking about (“Throw through the ball”) if basic instruction (“Put more topspin on it”) isn’t working for them.

Here’s an example of what Heaney’s redesigned curveball would look like compared to his previous version that lacked the desired depth:

Of course, command is an important factor to take into consideration. If Heaney isn’t able to consistently locate the pitch, despite applying the recommended arm slot, spin direction, or grip, then we’d go back to working on possibly adding additional sweep in lieu of depth, or even consider eliminating the pitch altogether.

Through this process of refinement, pitchers develop ways to more effectively throw a pitch. The process of changing the shape of a pitch – in this case, adding depth to the curveball – is generally more involved than what we have discussed here. It can become more varied and elaborate based on face-to-face interactions with the pitcher, as well as what their end goal is in terms of where/how the pitch fits with the rest of their arsenal ecosystem. Still, this hypothetical situation can help outline what a pitcher would work through in order to create the desired pitch shape and outcomes that come from altering the pitch.

Pitching strategist. Driveline Baseball pitch design-certified. Systems Administrator for a high school by day, I also provide ESPN with pitching visuals and am the site manager for SB Nation's Bucs Dugout.

Heaney’s breaking ball is a slider; I’d be interested to see the data in a different subsection of breaking balls

Huh. Well, the ‘major’ data-oriented baseball websites all call it a curve as well.