Pitcher, Author, Everyman, Hero: Jim Bouton (1939-2019)

Jim Bouton first made his mark as a star right-hander for the Yankees at the tail end of their 45-year dynasty, winning 39 games in the 1963-64 regular seasons (plus two more in a pair of World Series), and making one All-Star team (’63). Yet his second act — after he injured his arm, lost his fastball, and hung on to his career literally by his fingernails, trying to tame the knuckleball with the expansion Seattle Pilots — was far more interesting and impactful. Bouton began keeping notes chronicling his travails, which, with the help of editor (and fellow iconoclast) Leonard Shecter, became Ball Four. His candid, irreverent, and poignant “tell-some” account of his 1969 season with the Pilots, Triple-A Vancouver Mounties, and Houston Astros not only became a best seller, it revolutionized the coverage of athletes, and keyed a proliferation of inside-baseball books that went far beyond the diamond. Recognized in 1996 as the only sports book among the 159 titles selected for the New York Public Library Books of the Century, Ball Four brought Bouton enough fame and notoriety to last a lifetime. That lifetime ended on Wednesday, when Bouton, who was 80 years old and suffering from vascular dementia, passed away at his home in Great Barrington, Massachusetts.

With its candid glimpse into the lives of major league ballplayers — hard-drinking, skirt-chasing, amphetamine-popping athletes using four-letter words — as they attempted to cope with the pressures and the boredom of the game, Ball Four was raunchy and controversial. Set against a backdrop of social upheaval, the outsider Bouton often found himself at odds with his teammates regarding the war in Vietnam, race relations, politics, and the burgeoning union movement within the game, which would eventually challenge the Reserve Clause, leading to higher salaries and the right to free agency.

Amazingly, such an explosive exposé did not win Bouton many friends within baseball. Fellow players accused him of violating the sacred trust of the locker room. His ex-Yankees teammates were said to take it very hard, particularly Mickey Mantle, whose debauchery had previously been hidden from fans by writers who had sanitized heroes for public consumption. Bouton, whose major league career ended shortly after the book was published in 1970 (though he made a brief comeback with the Braves in 1978), was effectively blacklisted by the Yankees until 1998, after the tragic death of his daughter Laurie in an automobile accident prompted his son Michael to write an open letter to the New York Times, asking the team to help Bouton heal old wounds by inviting him to Old-Timers’ Day. They did, and Bouton was greeted with a warm ovation. His cap flew off on his first pitch, a signature from his playing days.

When excerpts of Ball Four first appeared in Look Magazine in the spring of 1970, MLB commissioner Bowie Kuhn tried to get Bouton to recant his claims and state that the book was fiction. “It was the perfect form of censorship,” the pitcher-turned-author recalled in 2010, on the occasion of the book’s 40th anniversary. “The publisher had only printed 5,000 copies on the grounds that nobody would want to read a book about the Seattle Pilots written by a washed-up knuckleball pitcher. Then the baseball Commissioner calls me in, and they have to print another 5,000 and then 50,000 and then 500,000 books…” Including 10th, 20th, and 30th anniversary editions with epilogues that created what MLB’s official historian John Thorn called “a candid, sometimes heartbreaking extended memoir without parallel in American literature,” Ball Four sold millions of copies worldwide.

I purchased a few of those, for myself, friends, and colleagues, but the first one that came into my hands was a dog-eared paperback nestled among many titles salvaged from a flea market by my paternal grandfather, Bernard Jaffe, when I was nine. I read and re-read Ball Four in all of its four-letter-worded glory, and integrated the wonderful compounds “shitfuck” and “fuckshit” — the go-to exclamations of beleaguered Pilots manager Joe Schultz — into my burgeoning, sailor-mouthed vocabulary. More importantly, at a time when I was becoming acutely aware of the challenges of growing up Jewish in Mormon-dominated Salt Lake City, Utah, the book stoked my own self-awareness as an outsider, presenting a menu of options for nonconformity that were more nuanced than simple, outright rebellion. Ball Four sowed an inner monologue that shaped my powers of observation and, eventually, my writing. With apologies to Roger Angell (whose The Summer Game arrived in a similar package from my grandfather) and Bill James (whose Baseball Abstract series laid the groundwork for all of us using newfangled stats to analyze baseball), it’s no exaggeration to say that no writer has ever had a greater impact on my life than Bouton.

Ball Four revolutionized the coverage of sports by shattering the culture of hero worship, but Bouton, whose courage, wit, and story-telling talent I admired, was the hero I was lucky enough to meet, and he retained that status as we crossed paths multiple times over the past two decades. Ball Four had long since counseled me on the dangers of such demystification, for Bouton had chronicled his own torment at the hands of Pilots pitching coach Sal Maglie, his boyhood idol grown sour and hapless, dispensing valueless advice while constantly second-guessing his struggling charges.

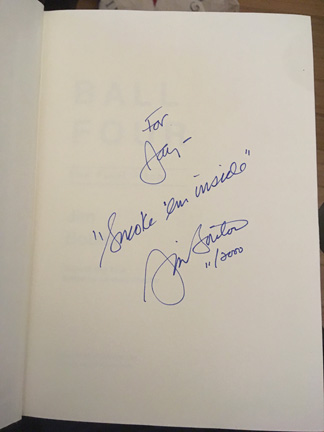

The first time I met Bouton was on November 3, 2000. He had launched the celebration of the publication of Ball Four: The Final Pitch, his 30th anniversary edition, earlier that day with festivities at Mickey Mantle’s Restaurant & Sports bar (Mantle had passed away in 1995, a year after burying the hatchet with Bouton). My pal Nick Stone and I trekked to the Bradlees on Union Square for a 7 pm book signing.

We were the first to arrive, even before the author, whom we watched descend the escalator and, to our surprise, introduce himself to us without assumption: “Hello, I’m Jim Bouton.” We had the honor and pleasure of talking to him about the book, baseball, and life in general for 30 or 45 minutes, finally yielding when another fan showed up and waited her turn. Bouton asked us about our favorite parts of Ball Four. The one that instantly came to mind for me was the Fred Talbot grand slam, in which a fellow pitcher — a former Yankees teammate, more adversary than friend — hit a bases-loaded home run that thanks to a well-timed promotion won a lucky fan $27,000. Bouton conspired to send a telegram to Talbot in the name of the winner, promising the pitcher $5,000 from the jackpot, a huge sum given Talbot’s $17,000 annual salary. Bouton retold the story with delight, adding flourishes that alas I’ve since forgotten. He told us of his plan for a book about the mindset of an athlete and even listened intently to the abstract of my unpublished treatise, “Graphic Design as a Form of Pitching.”

Neither of our planned works came to fruition, but the story of Bouton’s return to the Yankees’ fold during the 1998 season figured prominently in a piece I wrote for a continuing education course at The New School. It was my first formal attempt to write about baseball, about my own inner struggle with growing up as a third-generation Dodgers fan and then gradually taking to the Yankees after moving to New York City in 1995, culminating with my assembling a group to share a partial season ticket package to 15 games for the powerhouse ’98 Yankees. Between that nascent effort, the stimulus of meeting Bouton, and the death of my grandfather — who had regaled me with tales of watching Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Mel Ott, and Jackie Robinson — I was inspired to write about baseball, and did so by starting my Futility Infielder website and blog in 2001; as a print-focused graphic designer, I wanted to learn a new medium.

Two years later, I wrote about Bouton’s new book, Foul Ball: My Life and Hard Times Trying to Save an Old Ballpark, a departure from his worthy rehashes of his own career, and a gut-wrenching one. In spearheading an effort to renovate Pittsfield, Massachusetts’ Waconah Park, which had been constructed in 1919 but had lost its resident New York-Penn League franchise, Bouton stumbled into a story much larger than baseball, a silent war between the people of Pittsfield and the town’s morally bankrupt power elite, which had literally sold Pittsfield down the Housatonic River when General Electric was discovered to have contaminated the local waters with carcinogenic PCBs. Bouton’s intrepid pursuit of the truth forced him to terminate a contract with his initial publisher, for a top GE lawyer who had invested in the company subsequently demanded removal of certain passages. Waconah Park survives as the host of the Pittsfield Suns of the Futures Collegiate Baseball League, but the battle over the river’s cleanup has carried into the Trump era.

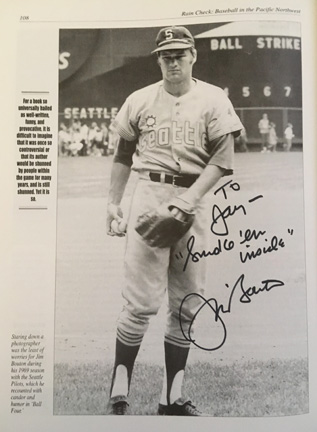

Fast-forward to June 2006, by which point I had introduced JAWS and was writing weekly at Baseball Prospectus. At that year’s SABR Convention in Seattle, Bouton gave the keynote speech at the awards lunch and appeared on a Pilots panel alongside former teammates Steve Hovley, Mike Marshall, and Jim Pagliaroni, moderated by Jim Caple. The occasion was as raucous as one can get in a hotel ballroom at 9 AM on a Friday. Afterwards, Bouton signed books and memorabilia; wearing my Mitchell and Ness replica Pilots number 56 jersey — a 30th birthday gift from friends in 1999 — I stood in a long line for my chance to spend a few minutes catching up with him. I told him that after our initial meeting I had begun writing first via my blog, and then professionally at BP; he was not only aware but had seen my Futility Infielder entry on Foul Ball thanks to a friend. He signed the photo featured in the convention journal Rain Check: Baseball in the Pacific Northwest, opposite Mark Armour’s fine essay about the book’s impact.

We took a photograph together (I should caution viewers that this was still three years before I began sporting a mustache).

Less than two years later, Bouton and I spent an afternoon working together in a professional capacity. The occasion was Roger Clemens’ appearance before the House Committee on Oversight and Governmental Reform, where Clemens challenged the findings in the Mitchell Report in an attempt to clear his name. I spent that afternoon in a Fox News Radio studio, where I was a guest commentator for the proceedings, a situation similar to when the Mitchell Report had been released two months earlier. Bouton — who in Ball Four had extolled the virtues of greenies and practically foreseen the whole steroid era when he wrote, “If you had a pill that would guarantee a pitcher twenty wins, but might take five years off his life, he’d take it” — was the other guest commentator, joining us via telephone.

For as thrilled as I was to share the airwaves with Bouton, I was also nervous, because in the wake of the Mitchell Report’s release, his tone had grown rather draconian, as he had suggested a lifetime ban for players who had taken PEDs with significantly less than a guarantee of such success. Fortunately, in our conversation regarding the hearings, the more iconoclastic version of Bouton re-emerged, offering a more nuanced viewpoint. Bouton conceded that he sympathized with the players in general, and viewed the commissioner, the Major League Baseball Players Association, and the owners, who had done little to protect the players from their own competitive nature, as all worthy of blame for the whole sordid saga. Neither of us bought what Clemens was selling that day, and for some reason I remember learning the word “dissemble” from Bouton as he described the pitcher’s evasive answers.

Two years later, in 2010, Bouton and Ball Four were in the spotlight for another round of anniversaries. He didn’t update the book, but participated in the opening of an exhibition at the Burbank (California) Central Library via the Baseball Reliquary. There he screened the world premiere of The Seattle Pilots: A Short Flight into History, an 84-minute documentary on the team, which after one season was hijacked by a used car salesman named Bud Selig and moved to Milwaukee to become the Brewers. I wrote about the festivities for The Pinstriped Bible.

My final encounter with Bouton came in January 2017, when I was invited to interview him on the occasion of the auction of the Ball Four original manuscript and ancillary materials — tapes and notes from the writing of the book, plus memorabilia from his career, including scrapbooks kept by his mother. The hope was that I would turn it into a piece for Sports Illustrated, where I was writing at the time. It was not until I called the phone number given that I was briefed on the 77-year-old Bouton’s deteriorating condition by his second wife, Dr. Paula Kurman, who explained that he had not fully recovered from a 2012 stroke and had difficulty speaking (as well as reading and writing). “His speech and language center was kind of blown out for awhile,” she said. Hence, she would assist with the interview.

Some dots connected. When I had watched The Battered Bastards of Baseball, a 2014 documentary on the Portland Mavericks, an independent minor league team with whom Bouton had launched a comeback in 1975, the pitcher had not appeared onscreen except in archival footage. His absence was notable, given that the movie’s title came straight from Ball Four, in which he had written, “Us battered bastards of baseball are the biggest customers of the U.S. Post Office, forwarding-address department.”

I did my best to cope with this unexpected curveball, reminding Bouton that we had connected on multiple occasions, including our Mitchell Report-related radio meeting and before that the Bradlees signing. While it wasn’t clear that he recalled either event, his chuckles and the warmth in his voice conveyed his enjoyment of being reminded how valued those encounters were. Kurman patiently coached me to avoid asking multi-part questions that her husband had difficulty following. “If you come at him with a multi-clause sentence, he often can’t pick that apart efficiently,” she said.

We surmounted that obstacle and spoke for 45 minutes, during which Bouton was quite lucid when recalling events from nearly a half-century ago. Sticking to my scripted questions, I began by asking him about his arm. “We were very lucky the stroke did not affect anything physically,” said Kurman. “If you were look at him, he’s still extraordinarily handsome, very lean and looks like he could pick up a ball and join any game.”

“I continue to throw a ball two or three times a week, a rubber ball that’s the same size and weight as a regular baseball.” said Bouton. “I have a cinder block wall at the other end of the property and it bounces back to me. I have a strike zone painted on the wall. Every once in awhile it goes over the top of the wall and I have to go find the damn thing, but it’s a lot of fun. It’s a familiar thing to me. I didn’t think about doing it, I just continued to do it, it seems like a natural thing, like breathing. Once in a while I think about locating [the pitch].”

Our conversation turned to his Pilots teammates. “We’re at an age where a lot of them are gone, and as each one passes, he truly mourns them,” said Kurman.

“You don’t think about how funny certain guys are, but I had been keeping track of them and I started to think of them differently,” said Bouton. “They were not just teammates or adversaries, they were incredible characters, and I started to think of them in a different way. At a time when normally a player would be a pain in the ass, he’s now the star of a great discussion in the bullpen. I came to love them, to tell you the truth. Guys I didn’t particularly like that much. There were some guys I would never spend any time with.”

Of Talbot, who had died in 2013, Bouton said, “I came to really like Fred Talbot, and when there was a notice in the newspaper that he died, I had to call up and ask the local newspaper about the circumstances. I had something nice to say about Fred for a website. I called him one of the greatest original characters I’ve ever known. I actually had tears in my eyes that Fred was gone now.”

“I came to think of these guys as different people. They were not adversaries or competitors for opportunities to pitch in a game or make the team, these guys were very special, all different, from all different parts of the country, different backgrounds. In those days there were very few players who were college kids. It seems like everybody came off of a farm or out of a mine. These were tough guys who didn’t have the background for this. Using Fred Talbot again, we were talking about players arguing with general managers, I said, ‘What do you do when they send you your contract and it’s a pitiful amount of money?’ Then Talbot said, “I sign them, but I throw in a few fucks.”

On the book’s legacy, Bouton said, “Whenever I think about Ball Four, I think about how fortunate I am to have been able to stick with the daily notes from the first day of spring training all the way to the end. I’m just so glad I did it, because I never would have been able to remember all that stuff. I had this marvelous cast of characters who were all thrown together at the end of their careers and nobody wanted them, and we had an opportunity to play on this team. … [The book] is just so dense with good things and funny things, inside things.”

Said Kurman, whose doctorate is in behavioral science, “I often say that although we had an instant attraction between us, I fell in love with him when I read the book because I understood that here was a brilliant scientific observation of a culture from the inside with an outsider’s point of view. He has that inside/outside thing so beautifully balanced. The structure — something he couldn’t have realized — it’s the same structure as fables which have lasted through all cultures for thousands of years, and that is the little guy going off on an adventure, running into obstacles, trying to prove himself, trying to find himself. That’s why I think people read it over and over again… It’s an everyman story.”

Alas, my interview with Bouton occurred during the run-up to the announcement of the 2017 Hall of Fame election results, for which I got to interview another personal favorite, Tim Raines. When the auction of Bouton’s archive didn’t reach its reserve price (it was expected to fetch $300,000 to $500,000), the story faded. My editor — who despite more than a decade in the sports media industry confessed to never having read Ball Four, a situation that I regarded with the same disbelief as when somebody tells me that he or she has never seen The Godfather or Star Wars — lost interest. The interview went unpublished (I will publish it at FanGraphs in the near future).

Nearly six months after our interview, Bouton appeared at another SABR convention panel, this time in Manhattan. Moderated by Thorn, the panel included Armour, fellow authors Mitchell Nathanson (the author of a forthcoming bio of Bouton) and Marty Appel, and Kurman. She had intended to use the occasion to make public the revelation that her husband was suffering from cerebral amyloid angiopathy, a form of dementia. “We wanted to make it public for the first time to you, because we consider this organization to be friends, and we have valued your support and friendship over the years.” However, a Sunday New York Times article by Tyler Kepner, who had visited the couple in Great Barrington and even played catch with Bouton, ran on Saturday morning in advance of the panel, and broke the news. “That’s the way it is,” said the unfazed Kurman.” Despite the revelation, the occasion was hardly a somber one. Quips from the panelists drew a boisterous response from an audience of about 700. You can hear a recording here.

Thereafter, Bouton largely receded from view. I wondered about his condition earlier this week when Thorn announced on his Our Game blog that the Library of Congress had acquired Bouton’s personal papers, an estimated 37,000 items, in 104 containers, with 73 gigabytes of digital files.

The final dots of Bouton’s life are connected, but thanks to the collection (“a treasure trove for scholars — of baseball, plainly — but also for those who would try to recapture what it was like to be alive in the Age of Aquarius and Vietnam,” wrote Thorn), the book on Ball Four will never close. Perhaps someday, we’ll learn new details about its writing, unearth anecdotes that will generate laughs anew among its legion of fans, so many of whom permeate sports media.

“Nobody ever captured the humor and humanity of ballplayers the way Bouton did in Ball Four,” wrote Kepner on Twitter on Wednesday night.

“Ball Four is perhaps the most important sports book ever written,” tweeted author Jane Leavy, who interviewed Bouton for her books on Mantle and Sandy Koufax. “Written with guts and gales of unwelcome laughter, it made everything else possible. Travel safe, Jim.”

That “everything else” includes this scribe’s career, but do not judge Bouton too harshly for that. I’m lucky that I had the chance to cross paths with him so many times, and to tell him what his work meant to me. I’m hardly alone.

Bouton’s book was a game-changer, not just in baseball but beyond. Wrote the New York Public Library in 1996, “Ball Four was the first ripple of a tidal wave of ‘tell-all’ books that have become commonplace not only in sports, but also in politics, entertainment, and other realms of contemporary life.” That’s an incredible outcome for a pitcher whose 1978 comeback with the Braves, during which he went 1-3 with a 4.97 ERA, dropped his career won-loss record to 62-63. In the end, Jim Bouton was a winner, and we are all the richer for it. Rest in peace, Bulldog, and smoke ’em inside.

Brooklyn-based Jay Jaffe is a senior writer for FanGraphs, the author of The Cooperstown Casebook (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017) and the creator of the JAWS (Jaffe WAR Score) metric for Hall of Fame analysis. He founded the Futility Infielder website (2001), was a columnist for Baseball Prospectus (2005-2012) and a contributing writer for Sports Illustrated (2012-2018). He has been a recurring guest on MLB Network and a member of the BBWAA since 2011, and a Hall of Fame voter since 2021. Follow him on BlueSky @jayjaffe.bsky.social.

Thanks for a very nice retrospective on Mr. Bouton, Jay. The way you weaved in your interpersonal recollections made it warm, personal and visceral — quite a bit like Ball Four itself.

For anyone who has not read Ball Four, I highly recommend it (and even for non-baseball fans). I read it for the first time myself just a few years ago, and aside from its interest as an inside story of baseball and baseball players, it is an amazing time capsule that captures the zeitgeist of America itself in that era. Get one of the later editions with all the added post-scripts from later years – that stuff is just as compelling as the original text.