Ralph Garza Jr. and the Sometimes Sidearmers

Back in November, left-hander Tyler Anderson signed with the Angels, and Ben Clemens wrote a super interesting piece about the deal. How did Ben make his article so interesting? By cheating. He was already writing a cool article about Anderson, so rather than start from scratch, he just folded the existing article into one about the signing. It was unfair to the rest of us who struggle to keep up with Ben even when he’s not juicing.

What Ben noted is that in 2020, Anderson started throwing his sinker from a lower arm slot against lefties. More recently, he started doing the same with some of his cutters. Dropping down some for his cutters meant that hitters could no longer assume that a low release point meant a sinker was coming, and it also improved the cutter’s performance. In 2022, lefties had a wOBA of .268 and an exit velocity of 79.5 mph against Anderson’s regular cutter. The drop-down cutter was at .124 and 76.3.

Inspired by Anderson’s novel approach, I went looking for pitchers who do the same thing. We’re not just looking for players who drop down some to throw certain pitches; there are too many of those to list. We’re specifically looking for players who dramatically change their arm angle depending on the handedness of the batters they’re facing. Once you weed out position players, who understandably have very inconsistent release points, there are only a few players who fit those parameters. Just six pitchers had a difference of more than three inches between their vertical release points against righties and lefties:

| Player | vs. LHB | vs. RHB | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ralph Garza Jr. | 5.59 | 4.02 | 1.57 |

| Rich Hill | 4.82 | 5.71 | .89 |

| Humberto Castellanos | 5.37 | 4.97 | .40 |

| Yennier Cano | 5.65 | 5.28 | .37 |

| Tyler Anderson | 5.73 | 6.07 | .34 |

| Joe Smith | 3.30 | 3.00 | .30 |

Ralph Garza Jr. is our headliner, so we’re going to save him for the end. Down near the bottom is our old friend Tyler Anderson. Dropping down on his sinkers and some cutters lowers his average release point to lefties by four inches.

Rich Hill is a name that probably shouldn’t surprise us either. As the oldest player in the league, baseball tradition demands that the newly signed Pirate also be the craftiest, and he is more than up to the challenge. Hill drops down 12.6% of the time. He mostly throws his slider to lefties, and in 2017, he started doing so from a lower arm angle once in a while. Also, after more or less abandoning the changeup earlier in his career, Hill brought it back in 2021. He throws it from a normal release point against righties, but drops down on the somewhat rare occasion that he throws it to a lefty. These are both changeups:

Hill’s changeup is an interesting pitch. He doesn’t seem to have a ton of control over it, and he often uses it as a waste pitch to righties, with the catcher setting up way off the plate. Hill threw 86 changeups in 2022, 28% of which were called strikes and 48% of which were balls. The pitch earned just one whiff last season, but he also gave up just one hit on the pitch, an infield dribbler.

Right-hander Humberto Castellanos drops down to three o’clock for some of his curveballs to right-handers, and it has definitely worked for him. Over the course of his career, righties have a .457 wOBA off his regular curve, and an average exit velocity of 92.9 mph. Those numbers are .272 and 81.2 against the sidearm curve. However, the sidearm curve lost some of its effectiveness in 2022, and he stopped using it quite so much. In 2021, 83% of his curves to righties were sidearm; in 2022, that number was 63%. Here are two curves from two very different arm angles, both getting absolutely rocked for doubles. It’s more fun with the sound on:

Dropping down isn’t a dead giveaway that a curve is coming, because Castellanos also varies the release point of his sinker to righties. Castellanos had a rough 2022. He made 11 appearances for the Diamondbacks before undergoing Tommy John surgery. He’ll miss the 2023 season entirely, and Arizona outrighted him in November.

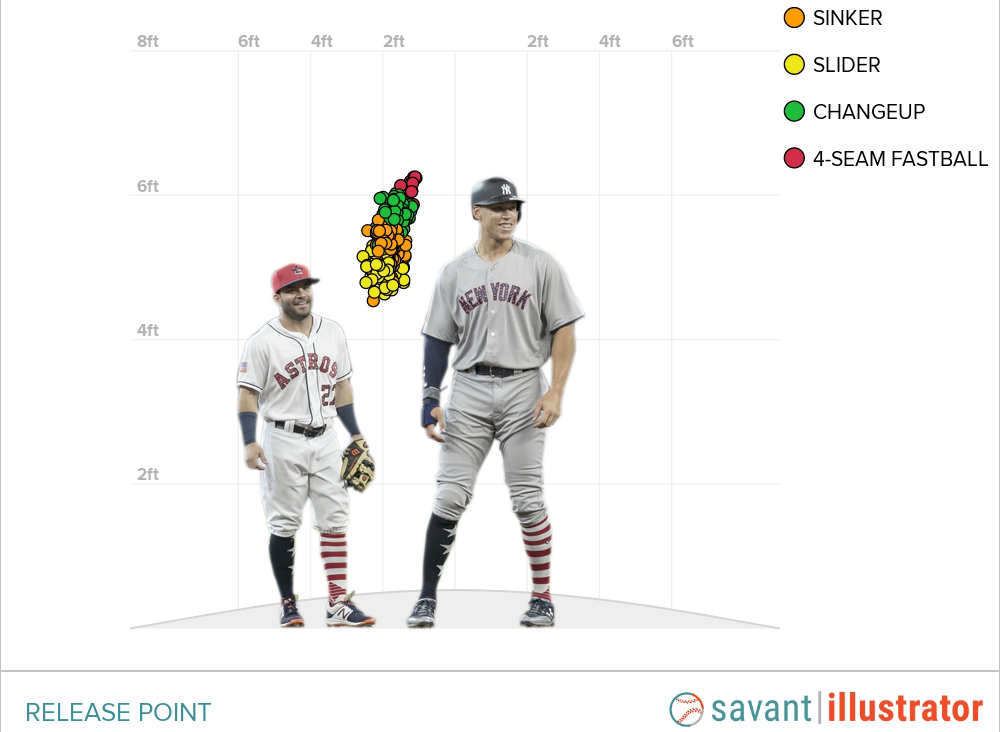

That brings us to Yennier Cano, one of four young pitchers who went from Minnesota to Baltimore in a deadline trade for Jorge López and Matt Bush last August. Baltimore’s front office likely saw some ways in which Cano could benefit from time in their new pitching lab. Extremely poor extension means that his 95.3 mph fastball plays like it’s 94.2. He made it into this article largely because of his four-seamer and slider. He releases the four-seamer high and only throws it to lefties. He releases the slider low, and only throws it to righties. The difference between the two is pretty extreme. You know those pictures we all love of Aaron Judge standing next to Jose Altuve? Judge is 13 inches taller than Altuve. The difference between Cano’s average slider and four-seamer? 12.8 inches:

The delineation between Cano’s pitches is so extreme that his release point chart looks like it was made by that kid from summer camp who organized all his Skittles by flavor before he ate them. I have to imagine that Cano’s 11.58 ERA and 5.78 FIP were at least partly due to the fact that his arm angle announced which pitch was coming with all the subtlety of an air raid siren:

Joe Smith, the 15-year veteran who spent 2022 with the Twins before being released at the deadline, has a somewhat similar release point chart. 86% of his sinkers come against lefties, and he releases them about nine inches below his four-seamer. The difference between Smith and Cano is that Smith varies the release point on his slider significantly, so there’s at least some overlap with both kinds of fastball. When he’s sidearm, the batter can expect a slider or a four-seamer. When he’s in full-on submarine mode, the batter can expect either a slider or a sinker:

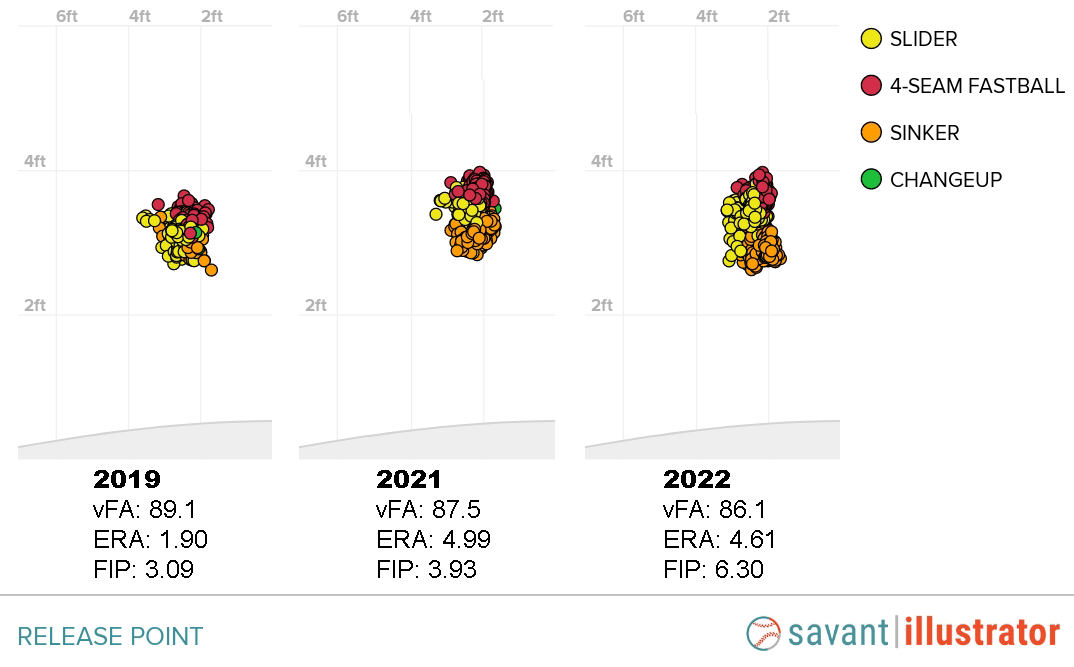

Interestingly, Smith’s release points weren’t always so distinct. The stratification has increased over the last few years, as both his velocity and his overall performance trended downward. It’s hard to say whether this change was one of the causes of Smith’s downturn, or a reaction to it:

The last pitcher on our list is the real prize. It’s not just that Garza drops down against righties, or that he changes his pitch mix depending on handedness. It’s that he commits to both strategies so fully that there’s absolutely no overlap between who he is to righties and who he is to lefties:

| Pitch Type | vs. LHB | vs. RHB | Vertical Release Point |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sinker | 0% | 57% | 4 |

| Slider | 0% | 40% | 4.1 |

| Changeup | 43% | 2% | 5.6 |

| Four-Seamer | 29% | 1% | 5.6 |

| Cutter | 23% | 0% | 5.6 |

| Curve | 6% | 0% | 5.6 |

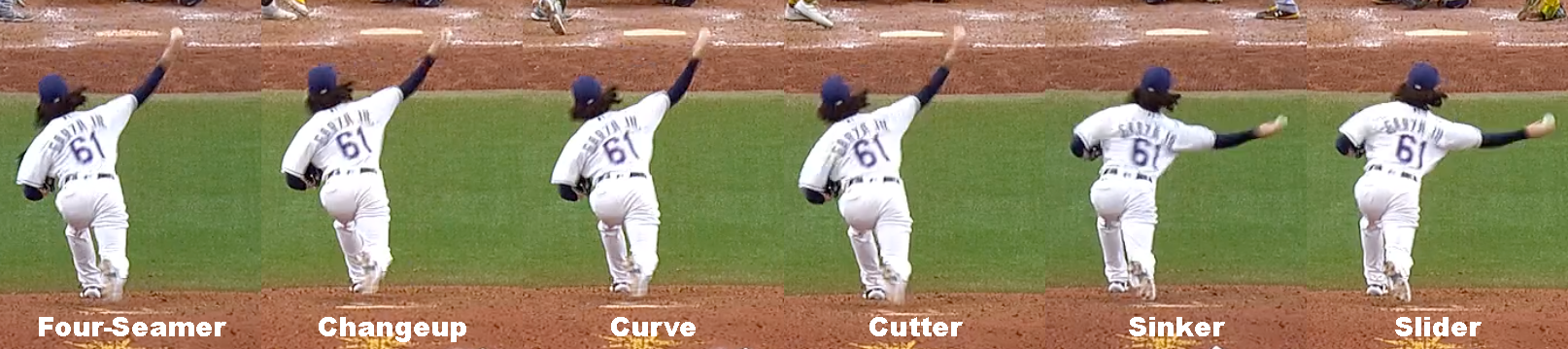

Garza’s release point against lefties is low, but he still has a fairly standard three-quarters delivery. He uses a three-pitch mix and sprinkles in the occasional curve. Against righties, however, he’s a full-on sidearm sinker-slider guy, with a release point more than 18 inches lower. The screenshots below were all taken from the same two-inning appearance on June 25:

Garza has been pitching this way since college. He was the 769th pick in the 2015 draft. The Astros encouraged him to keep his dual deliveries during his long climb to the big leagues, but in 2021, after just seven appearances, they designated him for assignment. He was picked up on waivers by Minnesota (where he just missed the chance to share a bullpen with Joe Smith), and he ended the 2021 season with a 3.56 ERA and a 4.88 FIP. The Red Sox claimed him on waivers in March of 2022, then waived him the day before the season started, at which point the Rays claimed him. Garza spent the season bouncing between Tampa and Triple-A Durham before being outrighted in August. He once again outpitched expectations, putting up a 3.34 ERA on a 5.17 FIP in six separate big league stints.

By ERA, Garza has been a productive pitcher in his two short seasons. He’s already got 0.6 bWAR. I wish I could predict with confidence that Garza would continue outperforming his FIP. I would love to watch him pitch more next year. It’s pretty fun to watch him throw back-to-back pitches like these two:

Unfortunately, Garza doesn’t seem like the contact managing type. In addition to scary walk and strikeout rates, he gives up tons of line drives. Among all pitchers with at least 100 batted balls in the last two years, Garza’s .361 xwOBA is in the 99th percentile. His exit velocity doesn’t look too alarming until you focus on where the damage is done. On fly balls and line drives, his exit velocity is in the 73rd percentile, and his pull rate is in the 97th. That’s particularly relevant because xwOBA (which already dislikes Garza) doesn’t account for spray angle, and pulled air balls are more than twice as valuable as ones to the opposite field. Garza does have a good groundball rate to righties, but his current batted ball profile just doesn’t set him up for success.

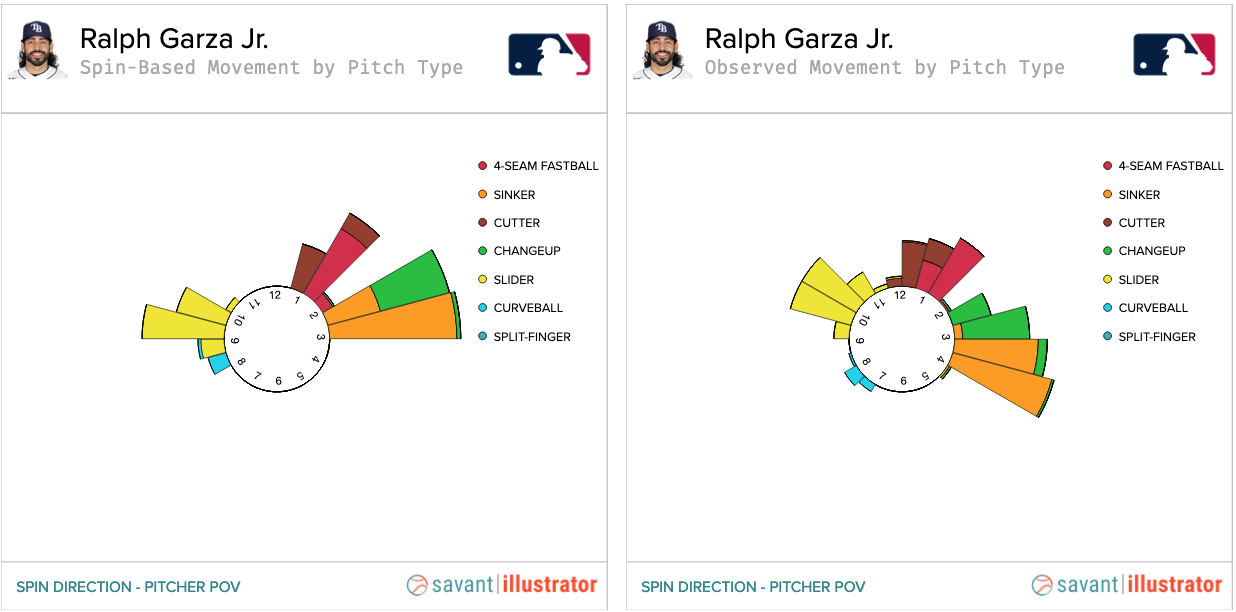

As you’d expect, Garza fares much better against righties. A look at Garza’s spin and movement profile offers an idea of how he could improve against lefties:

As you can see, his sinker and slider mirror each other pretty much perfectly. However, the same can’t be said for the pitches that Garza throws to lefties. Garza’s curveball is not a remarkable pitch by spin or movement, but it does mirror well with his four-seamer and cutter. Garza has only thrown 27 curveballs total so far, but the pitch has performed well in that small sample. Increasing his curveball usage, even if it’s just to bury the occasional one in the dirt, would give lefties something new to worry about, and make them come to the plate with a different plan. Lastly, I’ll note that Garza’s walk and strikeout numbers were significantly better in the minors, so there could be hope of improvement on that front.

Almost all pitchers alter their pitch mix depending on handedness, even stars like Max Scherzer, who completely shelves his slider against lefties. Deliveries are another matter. Pitchers work extremely hard to perfect them and get them to be as consistent as possible. Few would choose the grind of figuring out and maintaining two sets of mechanics (and in Garza’s case, six distinct pitches) if they saw an easier path to success. Hill’s long journey from indie ball back to MLB is well documented, but Anderson is the rare pitcher who was doing more or less fine before trying out a new arm angle. It’s a move for tinkerers and players without better options. Only two of our six players played a full 2022 season at the big league level, and only three are on a 40-man roster right now. In the end, maybe the scarcity of pitchers who drop down only some of the time is the best indicator of just how difficult it is to execute successfully.

Davy Andrews is a Brooklyn-based musician and a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @davyandrewsdavy.bsky.social.

Very fun piece!