Tyler Anderson’s New Plan – And New Contract

Can I let you in on a secret? I was already halfway through writing about Tyler Anderson when the news of him signing with the Angels broke because Anderson fascinates me. That article is more or less still in here. I also talk about how he fits into the Angels’ plans and how the contract comes into play at the end. It’s two reads for the price of one: one neat trick Anderson added in recent years, plus where he’ll pitch next season.

…

Tyler Anderson wanted it all. Normally, you have to pick a lane as a pitcher. You can be an over-the-top fastball type, throwing four-seamers that are equally tough on opposing batters no matter their handedness. Or you might opt to be a sidearmer; that gives you a huge advantage against same-handed hitters, but allows opposite-handed hitters to see the ball cleanly and gain a huge edge. Generally speaking, relievers are more likely to throw sidearm. It’s not a hard-and-fast rule, but it makes sense. Starters have to navigate so many different hitters that they’re bound to face opposite-handed ones more often.

Anderson has always been a starter, and he always sported an over-the-top release point. If you picture a clock face, his four-seamer spins in the direction of 11:00; mostly straight up and down with a tiny bit of leftward tilt, as befitting a lefty with a high release point. As I said above, that means small platoon splits, and that was indeed the case. Anderson allowed the exact same wOBA to lefties and righties in his first five seasons in the majors.

That made Anderson a perfectly average pitcher overall. In those five seasons, he compiled a 98 ERA-, 102 FIP-, and 101 xFIP-. That’s a nifty line, though his raw numbers looked worse given that he spent four of those seasons in Colorado. There was just one problem: he wasn’t doing a good enough job against lefties. Wait, what? Think about it. He had no platoon splits and was average overall. An average lefty starter would have done worse than Anderson against righties, and by the same token better against lefties.

One thing Anderson could have done with that knowledge is nothing. There’s no requirement that you dominate lefties as a left-handed starter, though it’s obviously preferable. But Anderson’s pitch mix – that over-the-top fastball and a changeup – didn’t exactly give him many great options against lefties. He threw a cutter, and occasionally a curveball, but neither was exactly the right option.

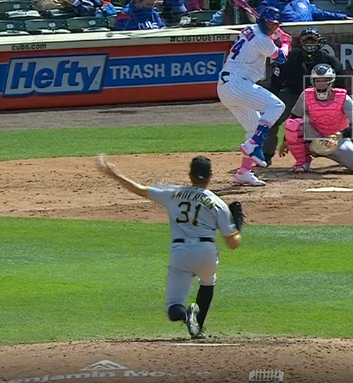

But Anderson clearly isn’t a do-nothing kind of guy. Late in 2020 and on into ’21, he dabbled with a new solution: why not become a sidearm pitcher? He debuted a new fastball release point, more or less a foot below his previous slot and clearly designed to plague lefties:

It can be hard to catch these things in motion, so here’s a freeze frame of Anderson as he released the ball:

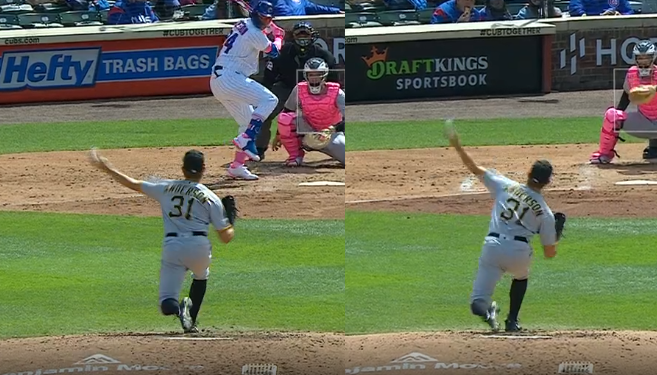

Just like that, Anderson had changed his stripes. He was no longer optimizing for all opposing batters; instead he was aiming for lefties with a low arm slot. You’d think that would put him at a disadvantage against righties, who make up the majority of the batters he faces. You’d be wrong. Here’s a pitch to Willson Contreras from that same day:

And here are those two release points side by side:

I’m not the best at displaying these, but I trust you get the idea. Anderson was now a sidearm pitcher and an over-the-top pitcher, depending on which was more useful at the time. He continued to experiment with that new trick for the rest of 2021, mixing in drop-down fastballs with his normal repertoire.

Note that I’m calling this a “drop-down fastball” instead of a sinker. It’s not really a sinker in the way we think about the pitch, though it does get a ton of horizontal movement. Sure, pitch classification systems call it a sinker, but I don’t buy it. It’s essentially Anderson’s four-seamer turned sideways. To me, sinker implies some seam-shifted wake and a pitch that starts with a four-seam fastball trajectory before fishtailing down and arm-side. Anderson’s “sinker” flies true, with little deviation from its initial movement.

That doesn’t make it any easier for lefties to hit. The pitch starts out behind them, more or less; he releases it three feet to the left of the center of home plate. It’s on a path towards the opposite batter’s box, but its movement – more than a foot of arm-side horizontal break – pulls it back towards the low and away corner. It’s a profoundly uncomfortable pitch to face, and Anderson knows it. He’s thrown it – sinker, drop-down fastball, whatever you want to call it – a quarter of the time to lefties for the past two years.

Of course, one gadget pitch isn’t enough, even if it’s a nifty pitch. Hitters get to watch video of their opponents, and even if you have a good sidearm fastball, they’ll eventually time it up. If all of your pitches are coming from over the top aside from one that you drop down for, hitters will associate that arm angle with that pitch. To put it mildly, you don’t want to tell the opposition what pitch is coming.

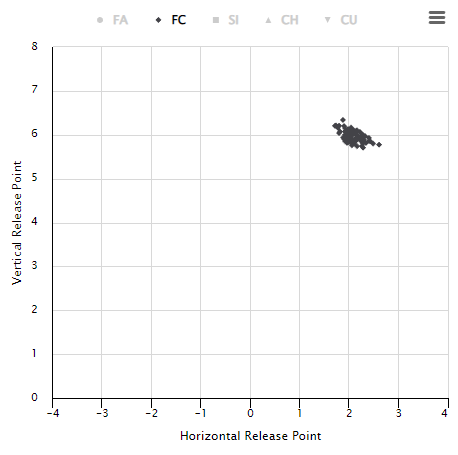

Again, Anderson had a solution. Here’s where he released his cutter in 2019:

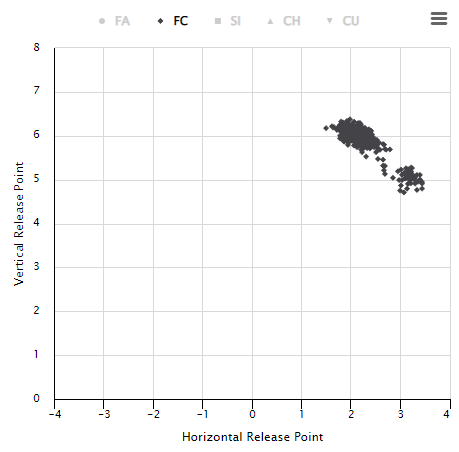

I hid all the other pitches so that you could see the cutter, but they’re all clustered around the same location. That makes sense: as far as I can tell, he mostly uses fastball mechanics for his cutter, and the release point thus mirrors his four-seamer. It’s a solid pitch in its own right that also flatters the fastball by giving hitters more to think about. Now, here’s where he released his cutter in 2022:

For the most part, he still releases them from the same spot, mirroring his over-the-top fastball. Now, though, he’s added a trick. He also throws a cutter from his low arm slot. The pitch moves differently from the different arm angles, naturally. It gets plenty of horizontal and vertical separation from his fastball, in the same way the high-arm-slot cutter does.

At this point, Anderson’s pitch mix to lefties is delightfully symmetrical. He throws roughly a quarter high-slot fastballs, a quarter low-slot fastballs, and makes up almost all of the balance (44% last year) with cutters of various types. He’s fastball/cutter – it’s just that there are two fastballs and two cutters. In 2021, he started to keep the ball on the ground more against lefties, which led to better results. He was starting to be a more “normal” lefty, with better results against same-handed batters. That higher groundball rate carried over into this year.

Of course, in 2022, Anderson added a different wrinkle – he reworked his changeup. It now drops more and moves more slowly, which gives it better separation from his fastball. He throws it more than a third of the time against righties, and it’s never gotten better results. He’s back to being a no-split pitcher, but in a completely different way.

Anderson is a delightful enigma of a pitcher. He throws over-the-top fastballs and changeups to righties, mixing in the odd cutter to keep hitters honest. He has that weird double-fastball, double-cutter plan against lefties. He’s changed the way he operates against every opposing hitter, and changed it in different ways. The result was a career-best season, with secondary numbers that suggest a lot of what he did might be sustainable.

The Dodgers seemed to think so – they extended him a qualifying offer, which would have paid him nearly $20 million next year. The Angels thought so too, giving him a three-year deal worth $39 million that will keep him in southern California through the 2025 season.

As far as I’m concerned, that’s a great deal for the Angels. I thought that Anderson would get something in the range of $15 million per year, and that if he fell short of that in AAV, he’d just take the qualifying offer and try again next year. It’s not that he’s wildly short of that, but even at my estimate of two years and $30 million, I thought he would be one of the bargains of the offseason. At three years and $39 million, the Angels are getting an affordable third year.

That might suit Anderson just fine. In his career before this deal, he’d earned approximately $17.5 million. After taxes and the cost of living, that made him wealthy, but not retire-to-the-country-in-style wealthy. This contract triples his career earnings with the stroke of a pen. Maybe three years and $39 million is a better deal for the Angels than two years and $30 million, but for Anderson, it’s a guaranteed $9 million extra. I don’t know about you, but I’d like $9 million guaranteed, even if some weighted expectation of my future earnings suggested that the “fair” value of that year was $10 million or something. Money has diminishing returns; locking in a contract that triples your career earnings must be awfully tempting.

Anderson will be the Angels’ second starter immediately, behind only Shohei Ohtani in the rotation. Throw in Patrick Sandoval and Reid Detmers, and the Angels might have an above-average rotation for the second straight year in 2023. That’s not to say they have no other holes – they need relief pitching and plenty of hitting – but shoring up a perpetual franchise weakness for $13 million per year should have their front office doing back flips.

Something feels off so far this fall when it comes to free agent signings. How did Anderson, who’s been league average or better his entire career as a starter, barely net more than Rafael Montero? It’s hard for me to imagine any team preferring Montero to Anderson – say what you will about the increased importance of a deep bullpen in the playoffs, but starters are simply more valuable than relievers. Perhaps it’s because Astros owner Jim Crane reportedly negotiated Montero’s deal himself. Otherwise, it’s hard to square the two.

Regardless of what it says about the broader free agent market, I love this deal for the Angels. If Anderson regresses mightily and returns to his pre-2022 form, he’s still a league average starter. That’s worth $13 million per year in my eyes, or at least close to it. The upside from there is considerable. The Dodgers were willing to pay Anderson 50% more than that for the 2023 season.

You can’t boil every contract down to “players like monetary security and teams like good players,” but it’s a good starting point. In my eyes, it explains almost everything that happened here. It doesn’t mean Anderson got a bad deal, or that other teams were asleep at the wheel. It just means that this fit made sense, and that both Anderson and the Angels were ready to get a deal done. I think this one will work out quite well for both sides, and that by midseason next year, a lot of teams will be kicking themselves for not offering Anderson what he wanted.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

According to Jeff Passan, the reason why Montero got that deal is because Jim Crane negotiated it personally.

I do think that part of the reason Anderson got this deal was because teams got a little skittish about the draft-pick compensation. But just on money and expected performance, this is a fabulous deal. And Moreno’s selling the team, who cares about the draft when this might be Minasian’s last chance to put a winner out there before new ownership brings in their own people?

IMO, the Angels should just go all in now on free agents that got the QO. Sign deGrom and Bogaerts too. Why not?

You’re right! We almost got Martin Perez, but he took the QO. His agent did apologize for hanging up on me when I offered 4 years at $19 million a year – he claims he thought I was making a prank call.

His loss.