Reports of Garrett Whitlock’s Decline Have Been Greatly Exaggerated

Four years ago, Garrett Whitlock’s emergence as an elite major league reliever was one of my favorite stories in baseball. How could it not be? He was a Red Sox Rule 5 pick who had been on the Yankees. It doesn’t get much better than that. He was a dominant multi-inning reliever right from the jump, with a 1.96 ERA over 73 1/3 innings pitched and excellent peripheral statistics across the board.

The years since then haven’t been so halcyon. He followed up his breakout with another good year of relieving, but a foray into starting went only OK. Whitlock started 2023 season in the rotation but pitched poorly, hit the IL three times, and ended the year as a mid-leverage bullpen arm. Then he tried the rotation again in 2024, but hurt his elbow after four starts and had internal brace surgery. All told, those three seasons came with a 4.01 ERA, a 3.71 FIP, and not a ton of volume.

That internal brace surgery brings us to this year. Internal brace procedures come with faster turnaround times than full Tommy John surgery, and Whitlock was ready for Opening Day. He started the season as a middle reliever and mopup man, entering in the fifth, fourth, and eighth (down four runs) for two innings apiece in his first three appearances. He didn’t look immediately restored, but who would? After he acclimated to the majors again, though, his command snapped back to its prior superb level, his secondaries improved, and he’s been nothing short of outstanding. Welcome to Garrett Whitlock’s second act.

Whitlock used a classic three-pitch mix in his breakout season: sinker, slider, changeup. The secret ingredient, though, was command. His fastball has dead-zone shape, and he doesn’t throw with overwhelming velocity, but he makes up for that by spotting it well. Front-door sinkers, 2-1 offerings that start over the plate and end up on the hands, dotted corners in two-strike counts; you name it, Whitlock can use his fastball to do it.

That three-pitch mix is going as well as ever. The only real change he’s made is throwing more sliders. More importantly, he’s regained his feel for command, and the results have been arrow up ever since. Since the calendar turned to June, Whitlock has pitched 23 innings, more than any other Sox reliever. He has a 1.96 ERA and a 1.41 FIP. He’s striking out more than a third of the batters he faces. He’s been one of the best relievers in baseball, full stop.

How is he doing it? Well, if the answer were just “the same way,” this wouldn’t be a very interesting article, so let’s dive into the particulars some more. It starts with his fastball. I’ve called it a sinker a few times now, and Statcast agrees, but that’s more technicality than anything else. He throws it with a two-seam grip, which is why it gets that classification, but it rises as much as it tails and doesn’t get grounders at an elevated rate; he even throws it high in the zone more than he does low. Don’t get too tied up on the nomenclature; the key point is that it’s a fastball with unusual characteristics, so it doesn’t fit any of the typical sinker/four-seamer/cutter labels we use to classify heaters.

Based on how I described it, his fastball sure sounds like it would be a hittable pitch. To get a sense of how hittable, I looked at how it performs when thrown over the heart of the plate — the most crushable location. And when opponents make contact with it over the heart of the plate, they’re batting .390 and slugging .580, both meaningfully north of the big league average for sinkers. But that’s one of the problems of comparing Whitlock’s pitch to a sinker. As I’ve already mentioned, it doesn’t share many characteristics with the average sinker.

For example, sinkers almost never draw swings and misses. On those aforementioned sinkers over the heart of the plate, hitters come up empty on about 9% of their swings. Against Whitlock’s fastball, hitters miss on 18.4% of offerings. That’s four-seamer territory, regardless of what you call it. And when Whitlock throws his fastball over the heart of the plate, he’s allowing a .403 wOBA, compared to the .408 mark for an average four-seamer to that location. So in addition to getting more whiffs than the average sinker when thrown to this most hittable location, his fastball is also allowing about the same damage on hard contact as the average four-seamer.

Maybe we aren’t great at calling it by the right name, or maybe fastball classification is just a hopelessly difficult endeavor. Regardless, Whitlock gets to an average-ish fastball in a weird way, and with that acceptable pitch, he floods the strike zone. First pitch of an at-bat? He uses his fastball 60% of the time, and he throws them for strikes 60% of the time. Behind in the count? He throws his fastball even more and lives in the strike zone 66% of the time.

With those huge zone rates – all way above league average – Whitlock gets into a ton of favorable counts. More than a third of the pitches he throws come with him ahead in the count. There aren’t a lot of bad pitchers in the top 10 for that statistic:

| Pitcher | Ahead% |

|---|---|

| Josh Hader | 40.0% |

| Tarik Skubal | 38.9% |

| Hunter Greene | 37.8% |

| Chris Sale | 36.1% |

| Shawn Armstrong | 35.6% |

| Jeremiah Estrada | 35.6% |

| Logan Gilbert | 35.3% |

| Matthew Boyd | 35.2% |

| Garrett Whitlock | 35.0% |

| Edwin Uceta | 35.0% |

Once he’s ahead, Whitlock often goes to his slider for the knockout. It’s a tough pitch to categorize, just like his fastball. It’s unremarkable in terms of shape and velocity, but it pairs well with his heater, and he can effectively move it around the zone or spot it low and away to right-handers. He sweeps it sometimes, too, taking a few miles an hour off and getting more horizontal movement. Again, it’s not a great sweeper in terms of raw movement, but the variety of looks adds up and keeps opponents off-balance.

Looking at his sliders provides a great window into how he does it. For the sake of our analysis, we’re going to lump together his traditional slider and sweeper, as his sweeper acts like a variation of his slider more than a distinct pitch, and refer to both simply as his slider. Both of our pitch models agree that his slider is roughly average stuff-wise. Both of our pitch models also agree that it’s roughly average location-wise; the sharp command he demonstrates is mostly with his fastball and changeup. Instead of average results, though, he’s making batters look foolish with his slider. They chase sliders outside the strike zone nearly 40% of the time, roughly indistinguishable from the chase rate that Chris Sale and Jacob deGrom get on their far-more-famous sliders. Meanwhile, batters swing at less than 60% of the in-zone sliders he throws (league average is 67%). They can’t figure out what to do and can’t recognize the slider in time, so they end up guessing, essentially.

Because of all those bad swings and bad takes, Whitlock’s slider does something that’s hard to wrap your head around. When he throws it in the zone, he misses bats at an average rate. When he throws it out of the zone, he misses bats at an average rate. Despite those two things, his slider misses bats at an above-average rate overall. How is that possible? It’s because a huge proportion of opposing swings come outside the strike zone, where batters swing and miss far more frequently.

My favorite part of Whitlock’s breaking ball is his ability to manipulate its movement. Take a look at the average movement on the pitch, and you’ll get an idea of how he’s changed it over time:

| Year | Velo (mph) | Horizontal (in.) | Induced Vertical (in.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 83.7 | 4.4 | 0.4 |

| 2022 | 83.2 | 1.6 | -1.4 |

| 2023 | 79.6 | 9.3 | -4.0 |

| 2024 | 82.4 | 7.8 | -3.3 |

| 2025 | 84.3 | 4.5 | -6.0 |

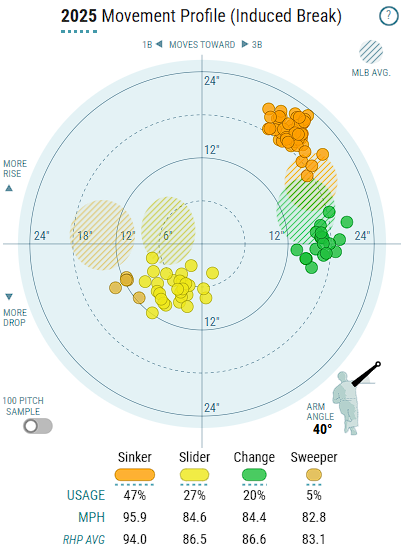

But even more than that, he changes it within games, within at-bats. Look at the wide dispersion in sweeper and slider movement, as shown by Baseball Savant:

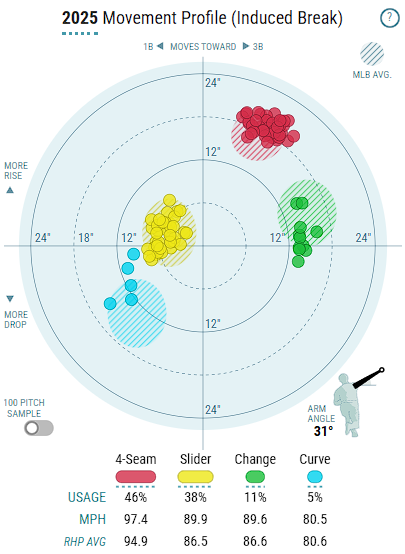

Compare that to deGrom, another great-command slider thrower, and you can easily see how much more variety Whitlock employs. Almost all of deGrom’s sliders (shown below) move the same. Whitlock’s (above) are all over the map:

In practice, that means hitters have a lot more area to cover. Given that Whitlock’s slider has never been a standout for generating swings and misses in any shape, I love his adaptation to confuse swing decisions by throwing a ton of different sliders. Here’s an example from May. In an 0-1 count, Whitlock took a little off his slider and tilted it downwards (zero inches of horizontal break, negative six inches of induced vertical break):

Then he came back two pitches later and threw another slider toward the same spot. The only difference? This one had seven inches of glove-side movement, enough to curl outside the zone and leave Maikel Garcia looking silly:

Another example? Sure. First, Randy Arozarena took a mighty hack at a gyro slider, only one inch of glove-side movement at 85 mph. Then Whitlock took a little off, trading two mph for five inches of glove-side break and an extra three inches of induced downward break. The result? Arozarena misjudged where the pitch was going to be:

Here’s an exceptionally nasty combination. Whitlock began with a diving slider with pure north-south movement — zero horizontal break, just negative nine inches of induced vertical break. Then, in a 3-2 count, he threw a much bendier one, with eight inches of glove-side break, to clip the corner and catch Jasson Domínguez looking:

I picked these examples carefully, of course. Whitlock isn’t varying his slider movement by six-plus inches against every batter he faces, and sometimes the variations don’t work out in his favor. But it’s surely an asset to have so much uncertainty around your slider that hitters can’t go up there with a good idea of what shape it will take. It’s a lot more dangerous to take a close pitch if you can’t tell whether it’s going to curve by three inches or nine.

That uncertainty works a lot better when you’re ahead in the count, but as we’ve already covered, that is Whitlock’s greatest strength. He gets ahead with his fastball and closes things out with a variety of sliders. Unless we’re talking about lefties – against them, he throws a changeup 30% of the time (11% against righties) to introduce a full three-pitch mix. That just makes their job harder; his changeup looks like a fastball out of hand before tumbling and fading. He throws it at the same velocity as his slider, but it falls six inches less and breaks about 20 inches the other way horizontally.

Honestly, I don’t need much convincing that Whitlock is good. He has a career 2.72 ERA as a reliever in nearly 200 innings of work, with a 2.85 FIP to match. (He’s at 4.29 and 3.97, respectively, as a starter.) But it’s a good reminder that the Sox have another relief ace despite mostly sitting out the reliever market at the trade deadline. He’s back toward the top of the bullpen hierarchy, getting high-leverage assignments left and right. He’s one of the best relievers in baseball – just like before.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

There were some injury concerns but I don’t think anyone questioned whether or not he’d be effective out of the bullpen if healthy. If there were reports of a decline or concerns about effectiveness, they pertained to his spot in the rotation