Rob Thomson Trusts Joe Ross

Joe Ross had a bummer of a 2024 season – a lower back injury ended his season after only 74 innings. He had a bummer of a start to 2025, too. Opponents were hitting him hard and he couldn’t miss a bat to save his life. But Tuesday night against the Mets, manager Rob Thomson said, Hey Joe, I trust you.

Ross was in the game unexpectedly early after Cristopher Sánchez departed with forearm soreness after only two innings. Ross came in to start the third inning, with the Phillies trailing 2-1. He came out of spring training in a short-relief role, but more recently he’d been used as a long reliever, and this particular situation called for multiple innings. So Ross came in and looked great, the best he has all year. After Pete Alonso greeted him with a single, Ross retired the next six Mets in order, two on strikeouts.

Two innings matched Ross’s longest outing of the year, and his pitch count was already up to a season-high 32. How long would you stick with a reliever who began the day with a 7.45 ERA, a 5.30 FIP, and an 11.1% strikeout rate in a one-run game? At some point, Thomson would have to take him out, and the bottom of the fifth inning seemed like the perfect time. The top of the Mets order was due up, which meant Francisco Lindor. And Francisco Lindor owns Joe Ross.

I’m not talking about some average batter-vs.-pitcher split. Lindor has crushed Ross, year in and year out. Before Tuesday, they’d faced off 11 times, and Lindor was 7-for-11 with three home runs. Every one of the homers went 400 feet. Lindor had seen 33 pitches and has swung and missed twice, compared to his three barrels. Lindor makes more contact, elevates more, hits the ball harder, and makes better swing decisions against Ross than he does against the rest of the league. He has homered against Ross’s fastball, slider, and changeup. After him? Literally Juan Soto. Sure, Soto’s off to a relatively slow start — emphasis on the relatively — but Ross is fastball-dominant even against lefties, and one sure way to get Soto out of a slump is with a belt high fastball. The next guy due up was Alonso, one of the hottest hitters in baseball.

Thomson could have told Ross to hit the showers and enjoy his excellent appearance. He could have gone to the single-inning brigade behind Ross in the well-rested Phillies bullpen to hold the line. But Philadelphia’s relievers have been a disappointment so far this year, and perhaps Thomson was looking for a spark. So Ross stayed in the game to face his own personal murderer’s row.

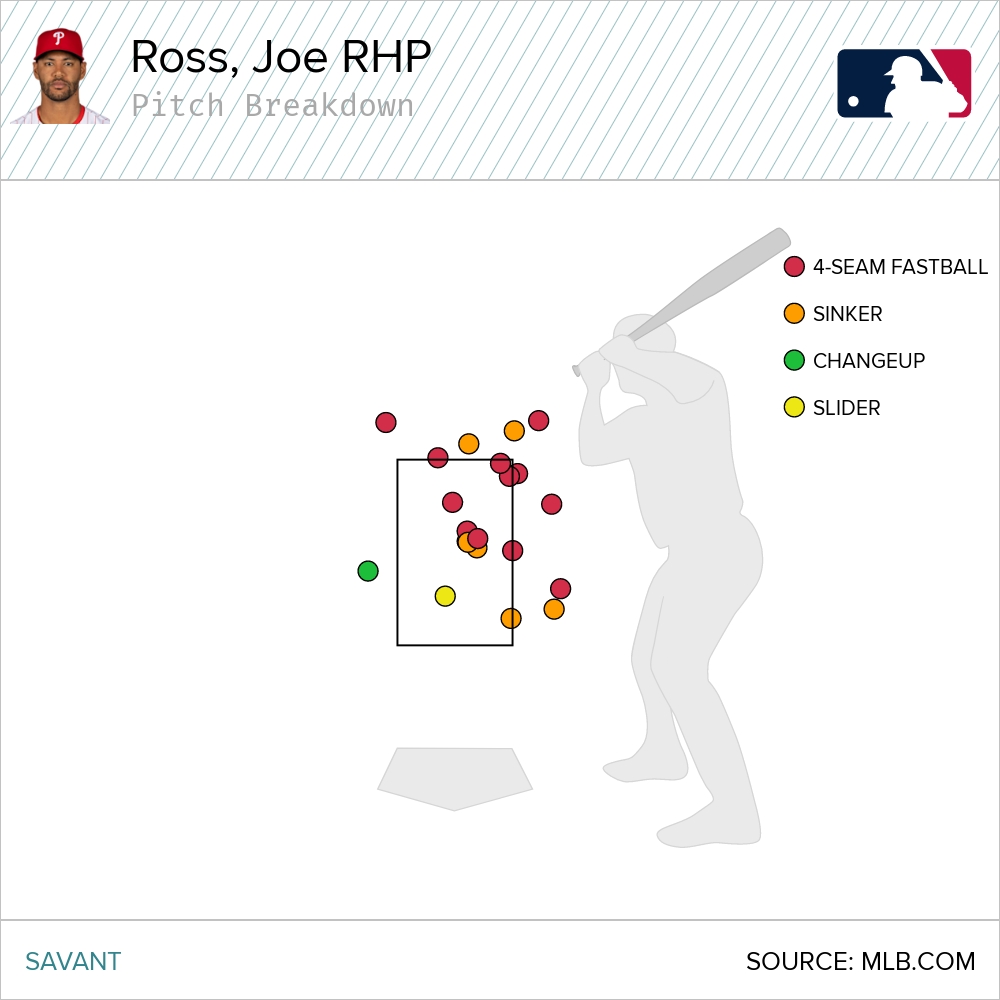

How do you pitch to someone who covers everything you throw? Ross stuck with his bread and butter. He started Lindor off the way he likes to start all lefties off, with a fastball up and in:

Now, I’m not saying this rises to the level of an exploitable pattern, but Ross is only looking one place with his initial offering when he sees a lefty batter in the box:

Still, even if Lindor had known exactly what was coming, he would’ve taken that pitch. It’s hard to do much of anything with a fastball that just dots the corner. After getting ahead in the count, Ross was emboldened to work the edges:

Again, it’s a classic pairing: fastball up and in, changeup low and away. Ross didn’t get the call on a borderline pitch, but he had a good idea there.

With the count even, Ross went back to the up-and-in fastball. This time, Lindor demonstrated the bind Ross was in:

Two pitches that didn’t make sense for Lindor to swing at — and he took them both. One pitch he could swing at – he swung, and hit the ball right on the barrel of his torpedo bat. Fortunately for Ross, Lindor fouled it back out of play. That’s the second-hardest swing Lindor has taken all year, 82.1 mph. He was ready for that fastball, in other words.

Lindor sees everything that Ross throws well, but he’s particularly good at picking up the slider. The last time Ross threw him one, he knocked it out of the park. So Ross made sure to keep his next pitch far from a hittable area, and Lindor took it comfortably:

On a different day, Ross might have been stubborn after that pitch, attacking Lindor with more secondaries off the plate. But Tuesday night, it seemed pretty clear that Lindor wasn’t going to be fooled. Sure, Ross could try to hit a corner, but hanging sliders and changeups has gotten him in hot water against Lindor in the past. He settled for a duel at high noon: fastball, upper edge of the zone, hit it if you can:

Lindor was completely fooled. He was sitting on something slow, so he was late to and below the upstairs fastball. He seemed baffled. He’d never swung and missed at a Ross fastball before. He was kicking himself the whole way back to the dugout:

Hey, sometimes you have to do something new to face your greatest fears. Sometimes you have to get lucky, too. With Soto now up, Ross tried to replicate his plan from the previous at-bat, aiming high and inside, but he missed. His first pitch was a sitting duck, a center cut fastball:

Look, Soto isn’t clicking right now, but you can’t throw him that pitch. Even in the depths of his “slump” – you have to be pretty good to slump with a 115 wRC+ – he’s tattooed fastballs. He’s put five middle-middle fastballs into play this year, three hit 105 mph or harder. He’s yet to swing and miss at one. A foul ball is the best you can hope for there.

Every pitcher makes mistakes; middle-middle fastballs are inevitable. They don’t always leave the park, or even end in extra bases. And so Ross stuck to his plan, attacking the upper-inside corner to lefties with his fastball:

Great pitch. Great outcome. Maybe Soto tags that one if he’s at his best, but Soto tags a lot of good pitches when he’s at his best. If Ross could just execute this plan every time, he’d fare much better against lefties. So now Thomson’s trust in Ross looked prescient. All he had to do was get out the guy with a 200 wRC+ to escape the inning.

Throughout his career, Ross has been far better against righties than lefties. Sinker/slider guys often have that issue, but Ross is extreme even within his archetype; over more than 1,000 batters faced from each side of the plate, lefties have torched him to the tune of a wOBA 22% higher than what he’s allowed against righties. You can see why right away; Ross started Alonso with the kind of pitch that you can’t really throw unless you’re facing a same-handed batter:

Lefties pick up on that spin much better, and the risk of hanging the pitch is high. Righties have more trouble picking up the ball out of Ross’ hand, and in fact he uses sliders peppered across the bottom of the zone early in the count quite frequently against them. Ross was feeling it, locating well with the exception of that one goof to Soto. He followed with a perfectly placed fastball:

Now he could see the finish line. Find one more strike, walk back to the dugout, and put a bow on the best outing of his year. But the last time he’d gotten Alonso in a hole, back in the third inning, Alonso lined a 103-mph base hit right back at Ross. So instead of trying to throw the same pitch but better – honestly, the first one was a pretty good pitch, Alonso is just hot right now – he started hunting a called strike three:

Those were some pretty good pitches, but Alonso is seeing the ball really well right now. Two clipped the zone, and Alonso fouled both off. The other two didn’t miss by much. But that wasn’t working, either, and you can’t keep throwing Alonso fastballs forever without asking for a home run. So Ross went back to the bendy stuff, and missed by a mile:

OK, fine, fastballs again. But that pesky Alonso wouldn’t go away:

Against a worse hitter, this inning would’ve been over. But Ross wasn’t facing a worse hitter. He was facing the best the Mets have right now. And on the ninth pitch of the at-bat, he made another mistake:

Not ideal, but also not a disaster. If you’re going to miss to Alonso with a mid-90s fastball, you’d rather have it end up on his forearms than over the heart of the plate. Ross would just have to deal with Mark Vientos, a much easier assignment, and he started things off the same way he’d operated all afternoon, with precise fastball command:

Just one last pitch to get out of the inning now. Ross stuck with old reliable, and nearly paid for it:

Five more feet, and I wouldn’t be writing this article. If you live by the mid-90s fastball, you’re certainly going to die by it from time to time. But for this night, Citi Field’s dimensions were just right, and Ross recorded a massive ninth out, the longest appearance of his season and certainly the toughest assignment of the bunch, too.

It’s a funny thing, trust. It doesn’t show up in the box score. The Phillies got comprehensively creamed. Ross’s seasonal line is still atrocious: 5.68 ERA, poor peripherals, and a 14.3% strikeout rate. But clearly, that’s not what the Phillies think of him. Nothing he’d done in 2025 before Tuesday night suggested that he had it in him. But Thomson believed in Ross, and Ross got it done. If he’s playing a key role for the Phillies down the stretch, it’ll be because he deserves it. But he couldn’t start deserving it without getting a chance to show his skills, and Thomson gave him the perfect opportunity.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

This is a great write-up, I really appreciate these granular (but narrative-driven) looks at particular sequences.

Yes, managers cannot play every game like it is a playoff and the ones who get solid contributions from the full roster gain an edge during the regular season grind. Dodgers and Rays are really good at it and Tigers do well too. Moneyball A’s were good at it as well.