Sean Doolittle’s High-Stakes Fight Against Pressure and Time

Sean Doolittle threw 10 pitches to Billy Hamilton on Saturday. Every one of them was a fastball, and all but one of them were in the upper third of the strike zone or higher. That’s what Doolittle does. No one in baseball throws a higher rate of fastballs than Doolittle’s 89.2%, and no one throws a higher rate of them in the upper third of the zone or higher than his 54.2%. He wears hitters out there, and that’s what he did to Hamilton. After a lengthy battle, the Braves’ new speedster didn’t have enough in the tank to get a piece of this last pitch.

That was a good outing for Doolittle. He retired all three hitters he faced, two of them on strikeouts. Even though Washington failed to rally in the top of the ninth, losing 5-4 to Atlanta, that kind of inning might have left a few Nationals fans feeling a bit more encouraged about their team’s overall outlook than they did before the game. That’s because recently, a dominant inning of work from Doolittle has no longer been the near-guarantee it used to be.

From 2017-18, Doolittle was incomprehensibly great. He threw 96.1 innings between Oakland and Washington and held a 2.24 ERA with a 2.27 FIP. He struck out 122 batters while walking 16. In terms of the game’s elite relievers, Doolittle was practically without equal. But this season, he hasn’t packed nearly the same punch. His ERA is 4.09, and his FIP is 4.23. His xFIP, which was a jaw-dropping 2.68 just last year, is now 5.05. He’s striking out two fewer batters per nine innings and issuing walks at his highest rate since 2015. After allowing just eight homers over the previous two seasons combined, he’s surrendered 10 this season.

The good news in those numbers is that a lot of the damage against Doolittle this season was done in a very short time frame. From July 29 to August 17, Doolittle threw nine innings and allowed seven homers. Again, that’s one fewer than the number he allowed in his previous 96.1 innings before this season. Included in that sample is one four-run, six-hit performance against the Mets on August 9, and another four-run game against the Brewers just eight days later, during which he allowed three homers in a span of four hitters.

That’s a shockingly abrupt halt in performance, and the Nationals treated it as such. According to Sam Fortier of The Washington Post, manager Davey Martinez watched film of Doolittle pitching against Milwaukee and didn’t think his closer was landing properly on his front leg, suspecting an injury. The team placed him on the 10-day injured list with knee tendinitis. He missed two weeks before returning on September 1, and since then, he’s thrown three scoreless innings.

That makes this seem like a pretty open-and-shut case then, right? A stud pitcher began to feel some pain, but he wanted to play through it with his team in a playoff hunt. His performance eventually suffered though, so he got the couple of weeks off that he needed and now he should be back to normal. That all checks out, and it would make for a nice ending to Doolittle’s brief struggles this season. But unfortunately for the Nationals, it might not be as simple as that.

One of the more challenging aspects of blaming Doolittle’s struggles on injury issues is that, for the most part, he’s throwing his fastball just as hard as he did a year ago. His velocity has dropped in three straight seasons, but he turned in his best year in 2018 with an average fastball of 93.8 mph. This year, his fastball sits at 93.5 mph. He did have his lowest average fastball velocity of the season at 91 mph in his game against the Brewers — the game in which his skipper noticed a physical problem — but that came directly after a game the day before in which he averaged 94 mph. If the injury flared up for the first time on August 17, that doesn’t explain what caused him to struggle over the few weeks prior to that.

In truth, Doolittle was already showing some reason for concern even before his rough stretch in the second half. Through July 24, Doolittle’s numbers weren’t far off from his past few seasons — a 2.72 ERA and 2.66 FIP. But his suddenly troublesome 4.76 xFIP suggested trouble may be brewing, and other data agreed.

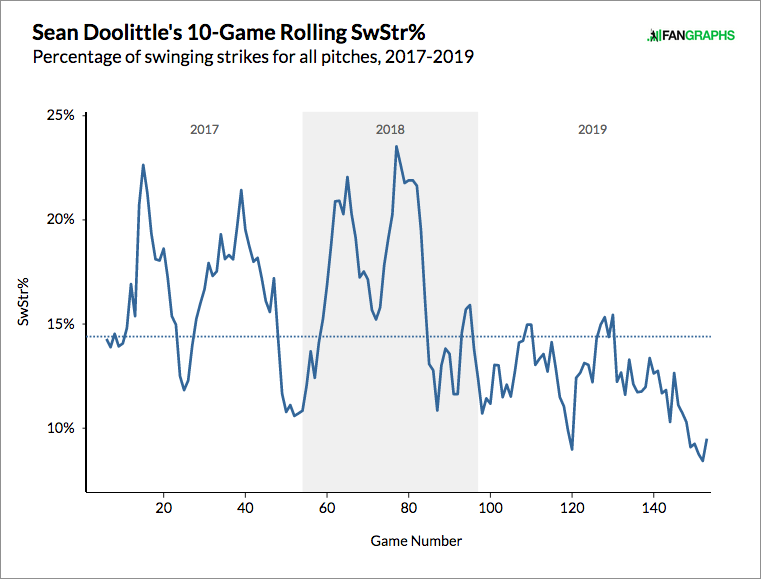

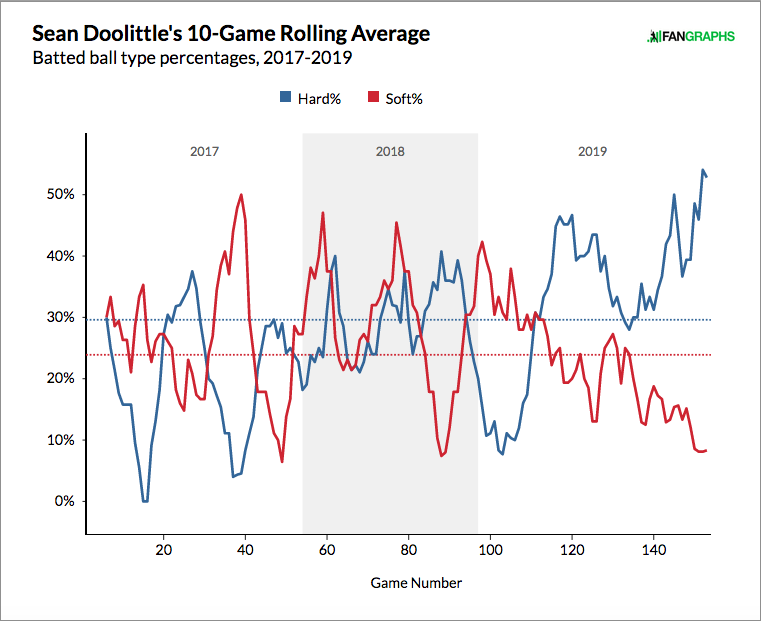

Doolittle’s whiff rates have been consistently below average this season, and they have mostly followed a downward trend all year, unlike previous seasons in which he would see a large spike or two during a hot streak. He’s also seen hard and soft contact rates travel in similarly upsetting directions as the year has gone on, reinforcing how consequential those missing whiffs have been. According to Statcast, Doolittle allowed xSLG marks of just .309 and .271 against the fastball in 2017 and 2018, respectively. This season, that number has shot up to .430.

He’s losing swings-and-misses with every one of his pitches. His fastball is obviously the main focus here because of how often he throws it, falling from a 33.4% whiff rate in 2018 to 22.3% this season. But his splitter and slider have experienced similar declines. All of this is happening despite the fact that Doolittle is not only maintaining his velocity, but also the movement on those pitches he had a year ago. Part of what makes his fastball so good is the rise he gets on it, and his vertical movement above average this season (3.9) is virtually identical with where it was in 2018 (4.1).

If his stuff is so similar, why have the results experienced such a sudden decline? Part of it could be fatigue. Doolittle has already appeared in 57 games this season, 14 more than last year and four more than any season since 2014. The biggest difference, however, has been how many times he’s been asked to throw on back-to-back days. This season, Doolittle has pitched 16 times on zero days off or fewer (he threw in both games of a doubleheader once), and has allowed 11 runs in 14.2 innings, including four homers. He’s pitched another 12 games on just one day of rest and given up four runs in 10.2 innings. Contrast that with his 2018 season, in which he threw with zero days off just eight times and with one day off nine times, and you might see how this season might wear him down faster. That fatigue may cause him to slip in his mechanics a bit and not hide the ball as well as he typically does, as well as give the hitter that extra millisecond of reaction time necessary to square the ball up.

That’s entirely speculation on my part, however, and there are plenty of smarter people than I in the Nationals’ front office working to solve the same puzzle. I’m relieved that they’re the ones that get to do the heavy lifting here, because the stakes for figuring out Doolittle’s sudden decline and trying to fix it couldn’t be higher.

Washington has had a great season, bypassing early struggles to work their way to 95% playoff odds with just a few weeks remaining in the season. It’s done so without the benefit of a strong bullpen though, with the 5.83 ERA posted by its relievers standing as the second-worst mark in all of baseball, ahead of only the Baltimore Orioles. You would not want to be staring down a National League playoff run armed with the Orioles bullpen, and yet that’s about the position the Nationals find themselves in. Next to Doolittle, the Nationals have handed the bulk of their bullpen innings to Wander Suero (4.43 ERA), Matt Grace, (6.36 ERA), Javy Guerra (5.01 ERA), and Tanner Rainey (4.62 ERA). Daniel Hudson, a midseason trade acquisition, took over the ninth inning in Doolittle’s absence, and has performed well between Washington and Toronto this season, yielding just a 2.86 ERA in 63 innings. But he’s coming off three straight below-average seasons of relief work, and his 4.29 FIP this season suggests he’s probably still closer to that kind of pitcher than he’s currently letting on.

It’s imperative for the Nationals’ playoff hopes, then, that Doolittle find a way to regain his form. That’s certainly an unfair amount of pressure to place on his shoulders, but as a 32-year-old who has spent all eight seasons of his major league career pitching out of the bullpen — usually in high leverage — he’s used to pressure. Maybe that age and experience is what’s conspiring to sink him, or maybe his last three appearances are a sign he’s figuring things out. Regardless of how he fares in his battle with baseball’s clock and the stresses surrounding him, he can take solace knowing he’s far from alone.

Each of last season’s top two finishers in WAR by relievers, Blake Treinen and Edwin Diaz, have seen their performances suddenly crater this season. A long list of other formerly dominant relievers, from Craig Kimbrel to Jeremy Jeffress to Raisel Iglesias, have faced similar woes. The volatility of great relief pitching has been showcased in 2019 as much as any year in recent memory, but there’s no one who needed to avoid those pitfalls more than the Nationals.

Tony is a contributor for FanGraphs. He began writing for Red Reporter in 2016, and has also covered prep sports for the Times West Virginian and college sports for Ohio University's The Post. He can be found on Twitter at @_TonyWolfe_.

Good article. I went looking at more things.

Velocity is fine, pitch mix is similar

I was thinking maybe it’s control. His BB% is up by a fair amount. Also, his Zone% is 50.9%, down from a career average of 54.9%. His F-Strike% is similarly down. Not great.

And when they are in the zone, Z-swing% is up (81% v 74% career) and Z-contact similarly. Batters are swinging at hittable pitches more, and making more contact when they do. That’s a bad combination for a pitcher.

More speculation: He’s not locating well, he’s falling behind, and has to throw more of those fastballs inside the strike zone. Those get hit, and frequently hard. Now I’m no mechanics guru, but it seems to me that a pitcher with an injury to the knee of the leg he lands on (which Doo’s is) might lose some of his ability to control where his pitches are going.

Also, can’t discount that opposing teams are more wary of high fastballs – both his approach and the increasing general approach – and are simply looking for the pitch/adjusting better than they have in the past.