Shortstops Are Hitting Like Never Before

Take a look at a 2019 WAR leaderboard and you’ll see some familiar names at the top. Cody Bellinger is having a whale of a season. Christian Yelich is hitting like Barry Bonds and is somehow second in the majors in baserunning runs as well. Mike Trout — well, you know Mike Trout. Look a little closer though, and you might notice something strange. There are four shortstops in the top 10 for WAR this year, and they’re not the usual suspects. Paul DeJong, Elvis Andrus, Jorge Polanco, and Javier Báez are all having great seasons so far, and if you had them as the four best shortstops in baseball this year, you’re a better prognosticator than I am.

Cast your eyes a little further down the board and you might see an interesting trend. Marcus Semien is 11th in WAR. Tim Anderson, Trevor Story, Xander Bogaerts, and Adalberto Mondesi are in the top 25, and Fernando Tatis Jr. isn’t far behind. Perennial stalwarts Andrelton Simmons, Corey Seager, and Carlos Correa are off to good starts. Shortstop, in fact, has produced more WAR than any other position this year.

Now, to some extent, that’s a referendum on how important shortstop is defensively. Only catcher has a higher positional adjustment than shortstop, and as a result only catchers have been worth more defensive runs this year. However, dismissing the prevalence of shortstops atop the WAR leaderboard as a defense-based illusion sells this current crop short. We could very well be looking at the best-hitting shortstop season of all time.

Let’s start at the very top with wRC+. This year’s shortstop class has produced a 107 wRC+ so far. That isn’t the actual best in baseball history, but it’s second only to 1874, and hoo boy are stats from 1874 weird. In that season, shortstops walked .9% of the time, struck out 1.2% of the time, and delivered a batting line of .305/.311/.372 in only 660 games. Let’s be reasonable here and throw out everything before the turn of the century. Cut those out, and the leaderboard looks like this:

| Year | wRC+ |

|---|---|

| 2019 | 107 |

| 1904 | 101 |

| 1908 | 96 |

| 1909 | 96 |

| 2018 | 95 |

| 1905 | 94 |

| 1917 | 93 |

| 1910 | 93 |

| 1907 | 93 |

| 2016 | 93 |

2019 shortstops are on top, and it isn’t particularly close. Strip out everything pre-integration, and the recent rise of slugging shortstops jumps out even more:

| Year | wRC+ |

|---|---|

| 2019 | 107 |

| 2018 | 95 |

| 2016 | 93 |

| 1947 | 90 |

| 2007 | 90 |

| 1964 | 90 |

| 1949 | 89 |

| 2005 | 88 |

| 2017 | 88 |

| 2002 | 88 |

Ask most baseball fans for the best shortstop-hitting season in history, and they’ll point to 2002. This was indeed a year of great shortstop hitters — Alex Rodriguez hit .300/.392/.623 on his way to a 10-WAR season, and Derek Jeter, Nomar Garciaparra, and Miguel Tejada all had sterling years. That’s all well and good — it was a top 10 season on the above leaderboard, after all — but 2002 also had 585 plate appearances of Neifi Perez’s .236/.260/.303 line, as well as a shockingly low-offense season from Rockies shortstop Juan Uribe, who hit .240/.286/.341 while playing half of his games at Coors.

This season has its fair share of laggards (Brandon Crawford is slugging .212), but it also has 16 shortstops with a batting line at or above league average. Freddy Galvis is hitting .297/.317/.485 and is the 14th-best-hitting shortstop this year. That 114 wRC+ would have been sixth-best in 2002. The depth of shortstop right now is simply stunning.

Now, as Dan Szymborski would surely remind you, it’s early in the year to make any rash proclamations. The season, after all, is only about one-sixth over. Shortstops as a whole have a .326 BABIP, and that’s not going to hold up all year — the highest single-season BABIP shortstops have recorded as a position is .304 in 2016. Well, FanGraphs has March/April splits going all the way back to 1974. Take a look at the best Aprils on record:

| Year | wRC+ |

|---|---|

| 2019 | 107 |

| 2018 | 97 |

| 1995 | 95 |

| 1996 | 94 |

| 1976 | 93 |

| 2002 | 90 |

| 2014 | 87 |

| 2006 | 87 |

| 2000 | 87 |

| 2013 | 86 |

Okay, so it’s safe to say that 2019 has been exceptional. Not only have we not had a season like this, we haven’t had an April like this. As Ben Lindbergh and Sam Miller recently pointed out though, rumors of a position’s demise (or emergence) are often greatly exaggerated. Positions have good or bad years without any rhyme or reason all the time. Without anything beyond “hey, shortstops have hit well this year you dope,” it would be hard to believe that anything has really changed. What gives? Why write an article about this now?

Well, basically because of sample size. Even if that April leaderboard is impressive, it’s not enough. Heck, even if this season kept up for the year, it might not be enough. Right this minute, if you stripped DeJong and Andrus out of the data, shortstops would only have a 103 wRC+ this year. That’s almost a convenient number, because DeJong had a 102 wRC+ last year — substitute in last year’s DeJong, and he’d blend right in. ZiPS projects Andrus for a 101 rest-of-season wRC+. It doesn’t take much, in other words, to cut several points off of the position of shortstop’s overall batting line.

Luckily we’re not limited to using just this year. Take a look at the post-integration leaderboard again. 2019 is first, sure. That’s why you’re reading this article, after all. 2018 is second though, and 2016 is third. Even 2017 sneaks into the top 10 at ninth. Shortstops didn’t luck into a few home runs this April — they’ve been hitting as well as the position ever has for years. Maybe Andrus and DeJong have been getting lucky this year, but they combined for a 91 wRC+ last year and shortstops had what was then their best-hitting year ever.

A theory of how well shortstops have been hitting doesn’t have to rely on a few fluky performances. Take a look at the best hitters of 2018 and you’ll see shortstops sneaking in all over the place. Manny Machado had a tremendous year (offensively) at shortstop. Francisco Lindor was his usual spectacular self. Bogaerts broke out. None of those three players are among the best eight batting lines for shortstops this year. The position is incredibly deep.

If it’s not a fluke, what could it be? I have a few theories. First, it’s really hard to be a terrible hitter in baseball right now and get consistent playing time. Analytics has roughly quantified the value of offense and defense, and even if the specifics haven’t been ironed out, teams are far less willing to play an offensive black hole to get their glove in the lineup. To pick a random year from the defense-and-speed 80s, 1985 saw 11 players qualify for the batting title with a wRC+ below 75. Five of those eleven were shortstops. If you could field, you could play shortstop.

Fast-forward to 2018, and three players in all of baseball had a wRC+ below 75 while qualifying for the batting title. One (Alcides Escobar) was a shortstop, and he hasn’t played a game in the majors this year. Teams simply aren’t willing to devote a season’s worth of at-bats to offensive lines that poor anymore.

If you have a sneaking suspicion that terrible batters were disproportionately shortstops in the past, you’re onto something. Using OPS+ as a metric, it’s clear that from the 1970s to the early 2000s, teams were throwing some pretty awful shortstops out there. Take a look at the number of 75-and-below OPS+ shortstops who qualified for batting titles by decade:

| Decade | Seasons <= 75 OPS+ |

|---|---|

| 1950-1959 | 27 |

| 1960-1969 | 29 |

| 1970-1979 | 56 |

| 1980-1989 | 45 |

| 1990-1999 | 36 |

| 2000-2009 | 47 |

| 2010-2019 | 24 |

Maybe there’s not a definite trend, but it’s suggestive of something. As an aside, Alcides Escobar is truly remarkable. Of the 24 sub-75 OPS+ shortstop seasons since 2010, he’s contributed seven. In 2013, he slashed .234/.259/.300 for a 49 wRC+ and played 158 games. If it weren’t for Ned Yost’s belief in Esky Magic, shortstops would have been doing even better.

That reason isn’t enough to feel good about. After all, the 1950s and 1960s had few truly poor batting seasons from shortstops, and they still fell short of the gold standard of recent years. Luckily, we can turn to the modern game for another answer. Think of the old days of baseball, and you probably imagine a diminutive but rangy shortstop making a play. Ozzie Smith was 5-foot-11. Robin Yount was a slender 6-foot. Pee Wee Reese was literally nicknamed Pee Wee, and we’re just talking about some of the standouts here. As recently as 2000, only four qualifying shortstops were 6-foot-1 or taller.

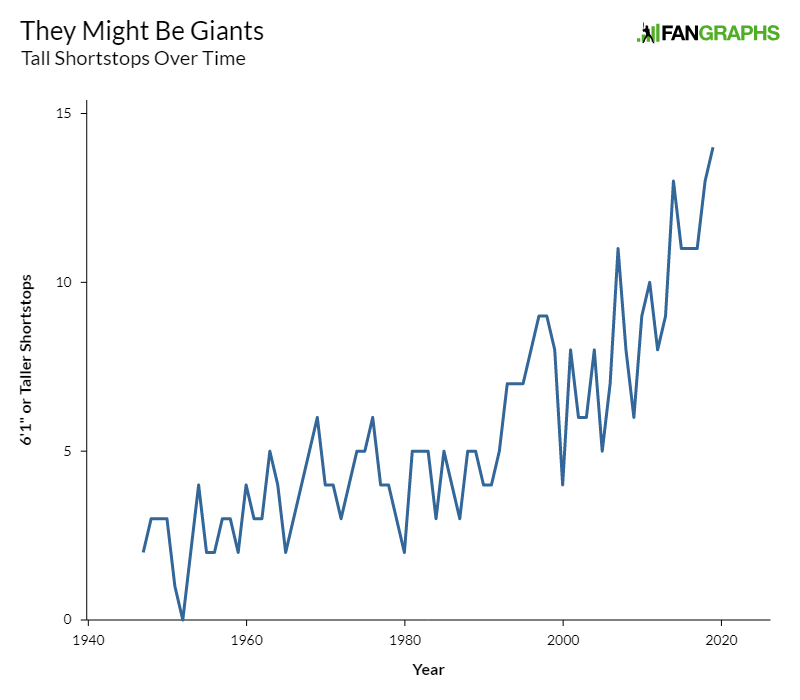

Height isn’t some magic tool that unlocks hitting. Still, it’s a good proxy for looking at power hitters starting to play shortstop. If Rodriguez and Jeter had come up in the 1970s, their 6-foot-3 height might have kept teams from playing them at shortstop. Cal Ripken was a large boy who stuck at short, but teams mostly shied away from playing people that tall and large at such a demanding defensive position. Take a look at the number of qualifying shortstops who stand 6-foot-1 or taller by year:

We’re living in an era in which giants roam the earth. This effect isn’t limited to shortstop, but it’s most concentrated there. The number of 6-foot-1 or taller batters has essentially tripled since the late 40s, but at shortstop it’s more like five-fold. Weight is even more telling. Before 1994, Ripken and Andre Rodgers were the only shortstops ever listed at 200 pounds or greater. This year, 15 shortstops fit the bill. Baseball is getting bigger and stronger, but shortstops are doing so faster than the rest of the league.

There’s one reason I haven’t yet considered. Maybe there’s just a wave of great shortstops playing right now; not for some macro reason, but just by pure chance. Lindor has barely played this year, but he’s arguably a generational talent. He mostly doesn’t fit the trends I’m saying exist. He’s under six feet tall and doesn’t weigh 200 pounds. His defense would play in any era. He’s just, you know, great. Simmons is now batting well enough that he’s a creditable addition to the position’s overall line, but he’d be playable even if he were a worse hitter. There’s no trend that can account for the best shortstop defender maybe ever happening to be a competent hitter.

If that’s the case, looking for trends is missing the trees for the forest. A few great individual players can sometimes tip the balance of the big picture. Sometimes greatness just happens. However, I think that we can safely say that this isn’t the only factor. After all, one of the truly remarkable things about this season is just how many shortstops are hitting well. It’s one thing to explain away Andrelton Simmons, and another entirely to say Dansby Swanson and Marcus Semien are the kind of generational talents that can break trends.

If you want my best guess, I think it’s a mixture of everything. Shortstops are getting taller and heavier faster than the rest of the league, and teams aren’t playing offensive deadweights like they used to. At the same time, a few outliers might be filtering through the game right now. Whatever’s causing it, shortstops are hitting like never before. If you’re looking through a lineup and wondering where the weak batting link is, your instincts will deceive you. Shortstops can rake.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Is this a byproduct of teams seeing fewer balls in play and being willing to sacrifice a little on the defensive side to gain significantly on the offensive?

This makes complete sense. Just looking at the fielding side – MLB shortstops were involved in (or credited with) 2.25 plays/game in 2006. Last year, it was 1.66 and this year’s runrate is identical to last year. That’s a huge drop which since the declines are prob comparable with 3B and 2B (and with the end of basestealing as well) means you just don’t need the rangy slaphitter defense-first guy anymore (except maybe in CF).

And my guess is that the defensive metrics and the notion of the ‘replacement-player’ haven’t adjusted as fast so the best draftees (who often did play SS from Little League thru college cuz that’s where the ‘team captain’ type position player has always played and ‘tradition’) tentatively ‘slotted’ as SS-until-they-grow-out-of-it are now focused on developing at the plate not in the field.

I’ll be interested to see WHEN that fielding decline for the position will result in a team putting lefties out into the field as 2B or SS or 3B. The ‘fielding demands’ have been the sole reason lefties have been excluded from those positions for a century or more. but that rationale no longer really exists.

The lefty thing is interesting, but I just don’t see it happening. The body contortion is too difficult that a lefty shortstop would have trouble making anything but the most routine play IMO.

it’s more valuable to the team and the kid to teach a talented athletic kid to hit and throw right handed and left than it is to throw a left handed kid onto the field at SS. Even high school teams are reasonably good at fostering switch hitting and throwing, and I imagine it’s a baseline training thing for good travel teams. That, the clear loss of initial defensive solidity from a left handed infielder, and tradition make it more likely that you’ll see teams try to teach kids to throw right handed more than try them out in the field.

Most of the really good players I played with growing up who ended up playing in college hit and threw left and right, even if not very well (our best relief guy pitched left handed but played 2nd right handed, if that makes any sense). If defense becomes even less valuable, you might see more good left handed bats try fielding right handed at the keystone or even 3rd. I doubt that the training and transition will happen once they’ve been drafted, but it might. Given the “Ease” of transition and declining value of defense, my bet is people will disproportionately try to teach players to throw right handed rather then throw them out with a lefty glove on.

I would disagree with the ease of transition. Yes – ‘natural’ lefties have an easier transition to doing stuff ‘righty’ than righties do to lefty cuz this is a right-handed world. But throwing (unlike batting/fielding) is small-muscle rather than big-muscle and small-muscle is harder to transition to the other side. If that transition was easy, you’d see a lot more pitchers transitioning from one side to the other since that creates a huge advantage. But that ain’t an easy transition.

I agree, thus “ease” and not plain old ease. The only guy who had any success with it, despite everyone working on it, was our shortstop. But on 3-4 throws a game? Having another really strong left handed bat at 2B was worth it.

Well lefty-throwers HAVE existed at C/2B/SS/3B at MLB level in the past. Jack Clements, Wee Willie Keeler, Jiggs Donahue, Hick Carpenter, etc. And that was during the anti-TTO era when they might have to turn 9-12 plays/game.

That explicitly changed when the AL and NL merged in 1904. Lefties in the NL farm system were required to be listed only as OF, 1B, or P prob cuz the AL was going to be allowed to raid NL farm system as terms of the merger and they didn’t want the NL to jerk them around. The only MLB level lefty player at those positions active at the time (Jiggs Donahue) transitioned from C to 1B and since then almost literally nothing lefty in the field at those positions.

So apart from ‘tradition’ and ‘these have always been the rules’, my guess is that the lower defensive value of those posns now COULD lead to some team realizing there’s a potential untapped advantage. With a lag cuz that ‘nothing’ extends down to Little League now.

The leagues never merged back then. (It’s been a gradual process since the Commishinor’s office was created.) They didn’t even have farm systems back then, so your explanation makes no sense!

MLB was created from the ‘national agreement’ in 1903 with something called the World Series (maybe you’ve heard of that) to determine whether the AL or NL champion was better.

The Natl Assn of Prof Baseball Leagues (today called Minor League Baseball) was formed in 1901 with overt ‘classes’ or levels – and became involved in the AL/NL merger discussions in 1903 when it came to how their players would be acquired under the new NL/AL agreement – where the NL was the only surviving ‘major’ league buying ‘minors’ contracts from the PREVIOUS national agreement of 1883 or so. I call that a farm system and even in 1901 it was called a ‘draft’ with ‘reserves’ (later morphed into Rule5 draft). And yes it was NAPBL/MiLB/’minors’ that agreed to ‘reposition’ their lefties as part of that legal agreement. Just as leagues had previously agreed ‘nationally’ to refuse contracts to black players.

There is no such thing as baseline training for good travel ball teams. Travel ball teams play more than they practice.

Throwing contortion depends heavily on positioning before the play. A lefty SS going to his left (towards 2b) to field a grounder has a much easier throw to first than a righty does. It only looks like contortion now cuz it is always righties making that ‘highlight’ play (v a rather routine play for a lefty).

Not to mention that there is an entire universe of lefty players whose glovework (absent throwing) has been deemed entirely irrelevant to playing baseball since the only positions they are allowed to play is OF or 1B (which means they have to either go CF/range/speed or massive power).

IOW – it ain’t 100% of possible plays in the field that favor righties. Probably only 50% with 20-30% neutral. And my guess is even that can be quite different from day-to-day depending on the likely handedness of the pitcher and of the opposing lineup. IOWIOW – even in the field I can see the potential for a lefty utility esp if they then have an advantage at the plate that day.

just anecdata, but from taking infield as a left hander you have to “flip” your body to really gun a throw across the infield. If you’re attacking a ground ball you’re basically moving the wrong direction to do that, so you have two bad choices- take a second to gather and gun, or try to make a throw moving the wrong way. And that’s not just a couple of balls a game, that’s basically every routine grounder if you set up deep and charge. Playing shortstop as it is played right now is almost impossible as a lefty, particularly turning double plays.

You could, I think, change the way you field by standing closer and backing up so momentum isn’t working against you, but you’d get eaten up a lot. You could also stand closer to third instead of second, which might open up the field a little but second can move over to cover and third can play more like first.

Yes – charging down bunts greatly favors right-throw fielders (on throws to first). But that means the decline in bunting also disproportionally eliminates that right-handed advantage. The increasing number of lefty bats (whether ‘natural’ or ‘learned’ or ‘ambidextrous’ lefty) also changes the distribution of ground balls in the infield.

The changes in the game shouldn’t simply be assumed to have an ‘equal impact’ on fielding. And ceteris paribus having a lefty glove in the mix of possible infield shift positions (2B/SS/3B are all allowed to change positions but 1B isn’t cuz they have a ‘mitt’ not a ‘glove’) opens up many more shift/positioning possibilities also.

There are a lot more ground balls than just bunts where a fielder is required to charge the ball.

Also the lefty advantage is going away.

Last year lhh wOBA was .319 vs .312 for righties. In 2002 it was .336 for lefties and .318 for righties.

Not sure if this is better and more LHPs or an effect of the shift.

Nobody can fully explain why, but lefty-throwing catchers have never worked out, either.

Its not IYO… its pretty much everyone who has ever played baseball.

Huh? Why do you think being left-handed is not a real problem for the left side of the infield? You have obviously never seen a lefty try to turn a double play. You seem to be assuming that defense just doesn’t matter and that we will eventually come to realize what you already know. You might have that backwards. It is more likely that teams trend back towards fielding better shortstops… especially if juiced balls ever go away. I guess if balls get even more juiced, then the league could just turn into HR derby and you can have whoever play SS that you want.

Crazy idea… the reason SS are not involved in as many plays is that they have less range and that there are more guys on the pull side of the field. It doesn’t mean you don’t need them. The fact that SS are involved in fewer plays doesn’t confirm anything other than how defenses are aligned or that they are worse at getting to balls. I am sure there is at least 1 ball per game that rolls through a misaligned defense – that doesn’t tell you anything about SS either.

I have been a lefty turning double plays. A lefty SS who’s covering second on a ball hit to the 2B/1B has a much easier throw to first than a righty does. For that matter, a lefty 2B or 1B has an easier throw to that SS covering second to initiate that particular double play (4-6-3 or 3-6-3 or 4-6-1 or 3-6-1) as well. For the same reason that righties are favored in the 6-4-3 series.

ALL fielding is situational and probabilistic – which is also supposedly what sabermetrics was intended to reveal elsewhere in the game. NOTHING is 100% no matter how many cliches and ‘traditions’ say so.

It is also impacted by teams using more advanced defensive metrics that has dramatically effected positioning. If you line the guy up in the right place he doesnt need as much range. Jordy Mercer is a good example of an oversized, under bat SS that was able to start for years (with about league average defense) with reliable hands and good positioning.

Advanced spray charts and shifts are probably a factor as well. The Cardinals’ starting shortstop, Paul DeJong, played minimal SS until he got to AAA, (mostly 2B/3B/C in his college career). But he’s a sharp guy (3.74 GPA in college, and was headed toward Med School had baseball not worked out), and his study of the game has paid off as he moved up the defensive spectrum as a pro.