Starling Marte Is (Not) Swinging Like Never Before

I was admittedly skeptical of the Starling Marte trade, mostly because I’m enamored with Jesús Luzardo’s potential. It makes one dream. The older Marte did not have such upside; for nearly ten seasons, he’s been a contact-first, speedy outfielder who was good but not great. But Oakland did solve their center field conundrum, and that about justified letting go a pitcher like Luzardo.

And while it’s not feasible to judge a trade a month after its completion, at this moment, the A’s have done exceptionally well. Marte has a 157 wRC+ for them so far and has also swiped 11 bags. Meanwhile, Luzardo has been struggling with command, an issue that’s long clipped his majestic wings. Then again, it’s not as if the latter is now helpless, and it’s not as if the former is now a markedly different player — or is he? To my surprise, Marte had been running a walk rate of 10.2% when I checked in on him; for context, his former career high is a 6.1% clip from 2014. He didn’t start drawing walks after arriving in Oakland — this is a season-long development — but things are different now.

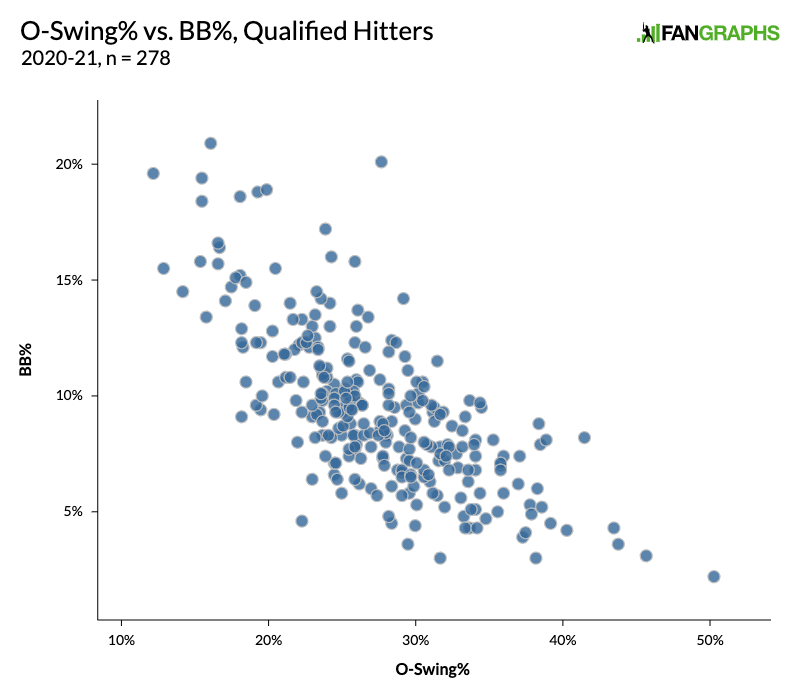

Marte is 32, and veteran hitters don’t magically improve their plate discipline without a measurable change. If you scroll through his FanGraphs page, it’s easy to spot the career-low O-Swing rate — 32.7%, to be exact. Not swinging at balls absolutely results in more walks, and in fact, O-Swing% is the best descriptor we have of walk rate. Here’s how the two line up in scatterplot form, using qualified hitters from 2020–21:

So, is it that simple? As with many baseball-related things, the better answer is more complicated. It’s true that Marte is running a career-low chase rate, but the margin is thin. In 2017, he had an O-Swing rate of 33.0% yet also recorded a walk rate of just 5.9%. This suggests that chasing less hasn’t always led to additional walks. Giving legitimacy to his newfound knack for free passes requires us to search for a true change — a sign of a new approach from someone with years of experience.

That can be tough to find, but we also know where to look. For example, though swinging at a ton of pitches seems like a bad idea, timing matters more than volume. If a hitter is swinging at a ton of strikes, that’s good! If he’s swinging at a ton of balls, that’s not so good. You could forgive a hitter, somewhat, for taking a bad hack when behind in the count. When he’s ahead, however, the cost of said terrible swing skyrockets because of how valuable a walk is. In other words, there’s a massive shift in run value.

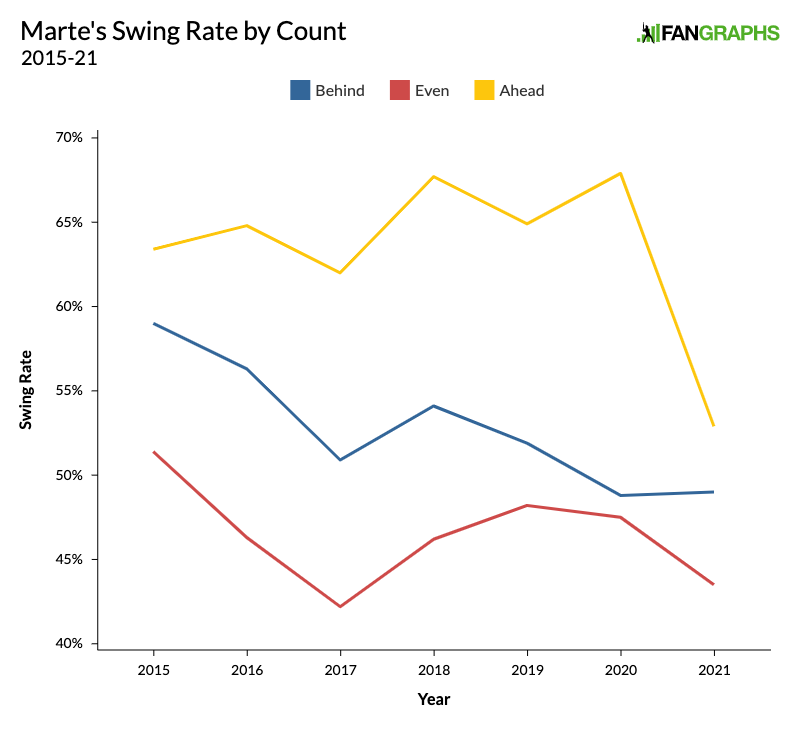

Assuming an average diet of strikes, a hitter could benefit from being more aggressive when behind, passive when ahead, and about the same when even. In Marte’s case, his behind-the-count swing rate hasn’t budged. It also hasn’t changed much in even counts. When presented an opportunity to draw a walk, though, he has stopped swinging:

This wrinkle adds a bit of nuance to our Marte discourse. Not only is he ignoring unattractive pitches, but he’s also swinging less on the right occasions. The task of linking the two eluded him in 2017, which likely resulted in a stagnant walk rate. But there’s always an opportunity to dig deeper; we can also split Marte’s ahead-in-the-count swings into ones against pitches in and outside the zone. Swinging less is a first step, but as mentioned earlier, it shouldn’t come at the expense of hittable pitches.

Time for a new graph! On display are Marte’s Z- and O-Swing rates when ahead in the count throughout the years:

The takeaways: Marte’s O-Swing% has plummeted when behind in the count, assuring us that he isn’t just ignoring every pitch in sight. We can also catch a glimpse of how his strike zone recognition went amok in 2020: He basically went after half of would-be balls in favorable situations, which I have to imagine affected his offensive output.

On the flip side, Marte’s Z-Swing% has also experienced a decline. Maybe he should ramp up the aggression versus strikes (more on that later), and maybe he is missing out by not doing so, but I’d argue this falls into the range of acceptable trade-offs. Sure, that willingness to forego strikes can hurt, as they might account for the slight uptick in year-to-year strikeout rate. Overall, though, it’s a profitable endeavor. When it comes to run expectancy, the cost of an out relative to an average plate appearance is roughly equal to the relative benefit of a walk. Marte is squarely in the red: His current strikeout-to-walk ratio is leaps and bounds ahead of previous ones.

And considering Marte’s base running prowess, walks perhaps benefit him more than the average ballplayer. Not that having a below-average on-base percentage necessarily prevents anyone from stealing — just look at Billy Hamilton’s numbers — but might there be an unquantifiable element. This season, Marte’s stolen base success rate is another career high, sitting at 92%. Does having more stolen base opportunities enable him to be selective in his thievery? This is merely a thought, but it’s something, and it felt like enough of something to include.

As a metric, a hitter’s walk rate isn’t smooth at all. It’s disjointed over a window of time, mainly because walks aren’t consistent. They also don’t occur as often as, say, swinging strikes, so what happens is a deluge of walks followed by a complete absence. Nonetheless, it’s possible to view large trends using rolling averages. What’s the one problem with Marte’s new approach? He hasn’t been drawing as many walks in recent weeks:

That isn’t entirely on him, though. Rather, there’s been a subtle change, one that he may not have noticed yet. We as analysts have the benefit of a holistic view, whereas athletes are focused on one at-bat or pitch at a time. And as Marte started swinging less, especially when ahead in the count, pitchers seem to have taken notice. If an opposing hitter is becoming increasingly passive, why not offer him strikes? That thought process is visible here:

Marte’s zone rate reached a minimum halfway through the season, but since then, it has gradually climbed. The shape of the graph is illustrative of a sort of cat-and-mouse game. In the beginning, pitchers offered Marte a similar rate of strikes as before, and he drew plenty of walks, preying on their assumption that hitters stick to what they know. Months later, pitchers realized their mistakes and made the appropriate adjustment. Now the ball is back in Marte’s territory. How does he respond? Does he stay put, trusting the walks will still come, or does he strive to swing just a bit more?

Or maybe Marte won’t tune into that side at all. There’s a chance what I mentioned isn’t really having an affect on his walk rate; as with everything, there are bound to be ups and downs. At a down period, though, he is still walking like he’s never before, and that’s the bottom line. It’s hard to restrain yourself from chasing this deep into a career. It’s even harder to focus selectively on a type of count. Marte has accomplished both, and he’s reaping like no other. Detractors will point to his .385 BABIP, which is indeed doing much of the heavy lifting. But even if we artificially adjust it to resemble his career average, the added walks mean he still ends up in the ballpark of a 120 wRC+. That’s a solid hitter even without the defense and base running.

For a while, Marte’s production tended to fluctuate, which was the consequence of his style of play. With a new taste for discipline, though, he’s added a much more sustainable source of it. The walk rate isn’t much in a vacuum, but when considering where Marte existed before, it’s a surprising development. Hitters like Joey Votto and Brandon Crawford are stealing the resurgent veteran spotlight. Let’s leave a spot for Starling Marte.

Justin is an undergraduate student at Washington University in St. Louis studying statistics and writing.

I think for the most part I can accept that decrease in z-swing% for the subsequent decrease in o-swing% since not every pitch in the zone can be sent 450+ (unless you’re Vlad Guerrero)

Yes the old saying was to look for a particular pitch in a particular zone when ahead 2-0 or 3-1. Swinging at more strikes might mean a lower quality of contact. I’ve no idea whether his BABIP or ISO are driven by extreme selectivity when ahead but they might be.