Stephen Strasburg’s Big Zig

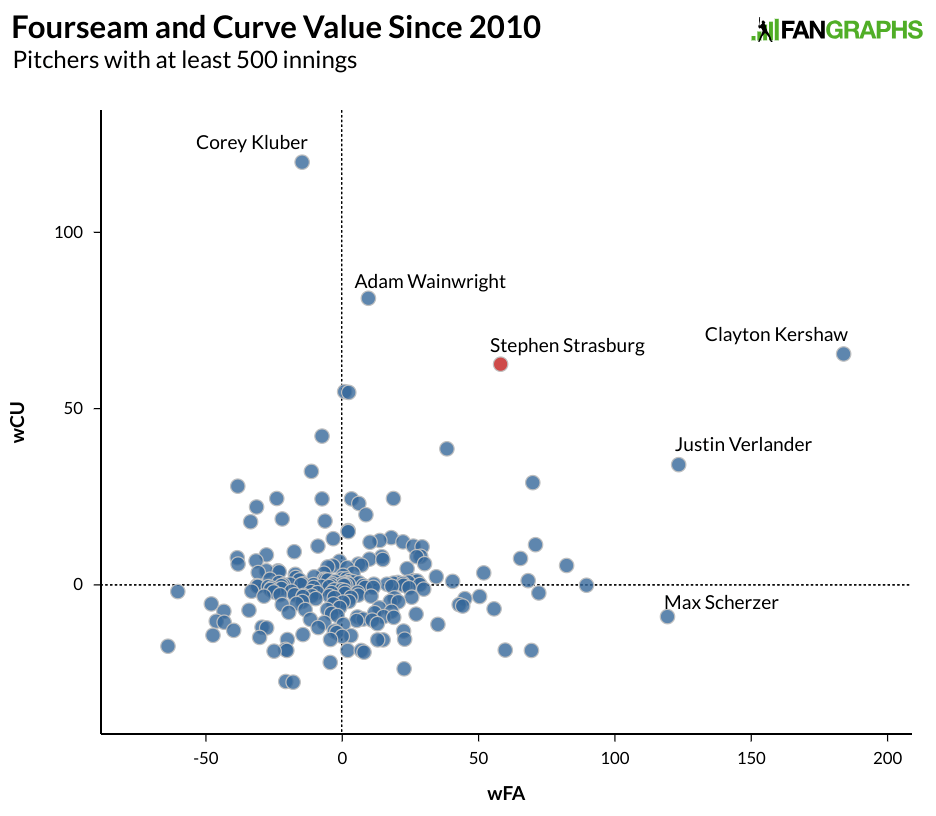

Over the last decade, pitchers have striven to be more and more like Stephen Strasburg. While Strasburg has always had one of the better changeups in the game, the 30-year-old righty has long used a four-seam fastball up in the zone paired with a big curve to dominate hitters. It’s a combo the Astros have famously used to successfully transform multiple pitchers, but almost nobody has been better than Strasburg with both the four-seamer and the curve over the last decade. The graph below shows all pitchers with at least 500 innings pitched who have thrown a four-seamer and curve, and the total run value the two pitches have produced.

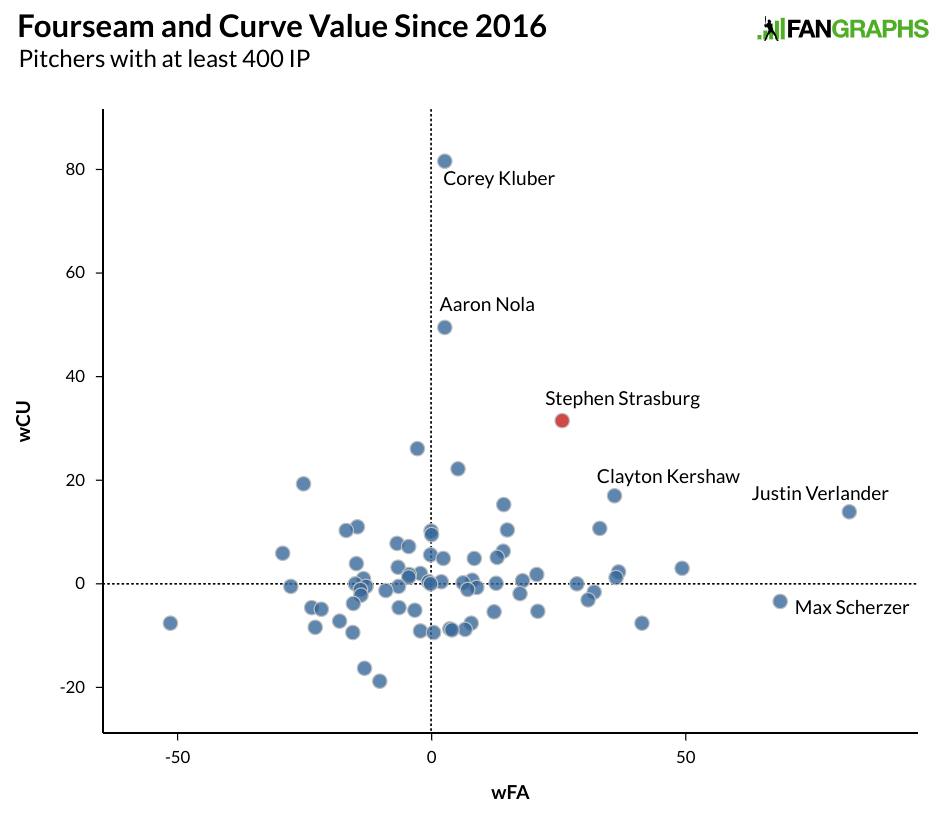

Sure, Clayton Kershaw is on another planet, but Strasburg is the only other pitcher at least 50 runs above average on both pitches. Since 2016, he’s been the best at combining the fastball and the curve to get great results.

Some pitchers have great fastballs and some pitchers have great curves, but Strasburg has been the best at getting value out of both. This season, Strasburg is throwing more curveballs than at any other point in his career and despite a velocity loss in the early going that has come most of the way back, he is having a very good season after a somewhat disappointing 2018 campaign. In nine starts, Strasburg has pitched 57 innings, struck out a third of the batters he’s faced while walking just 7%, and put up a 2.74 FIP and 1.7 WAR; that ranks fourth among all pitchers in baseball. It isn’t the increased curveball use that demands our attention, however. What’s curious about Strasburg this season is that unlike the rest of baseball, Strasburg is pitching his four-seamer less so that he can throw a sinker.

On its face, throwing more sinkers seems like a pretty poor strategic choice. Over the course of his career, nearly 600 plate appearances have ended on a Strasburg sinker, and he’s walked more than he’s struck out, with batters hitting for a .298/.363/.454 slash line with a 136 wRC+. By value, the pitch has been -4.5 runs below average during his career with a paltry 5.6% whiff rate. Jordan Hicks throws his sinker 104 mph and he can’t get whiffs on the pitch. The pitch is harder to control due to its movement and when it misses up, it ends up right in a hitter’s wheelhouse. That Strasburg, who has a plus four-seamer, plus curveball, and plus change, would go away from his strengths towards a pitch that has given him bad results doesn’t make a lot of sense.

There are multiple potential considerations to shifting some four-seamers to two-seamers. The first is that in a somewhat disappointing 2018 season, Strasburg’s four-seamer, which has decreased in velocity, wasn’t quite as good as it used to be. Twelve of the 18 homers Strasburg gave up a season ago came on the pitch. While most of his peripheral plate discipline numbers were in line with his career stats, a less-is-more approach could make his four-seamer better. That’s been the case so far this season, as Strasburg’s swinging strike rate (at 11%) on the four-seam is by far the highest of his career.

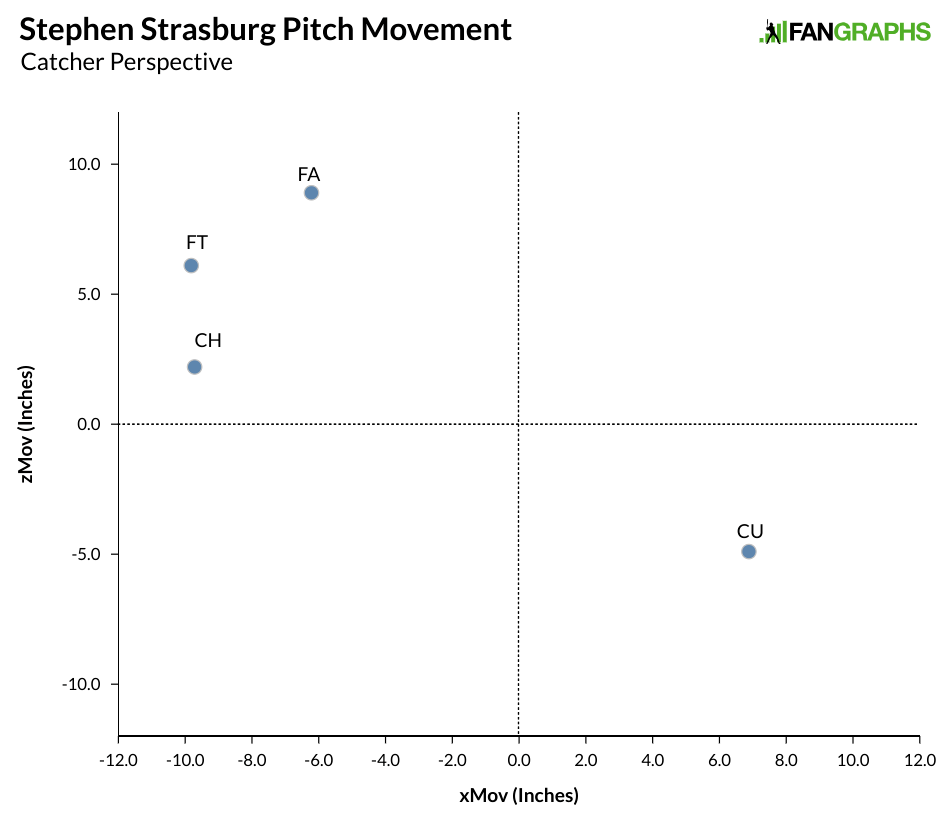

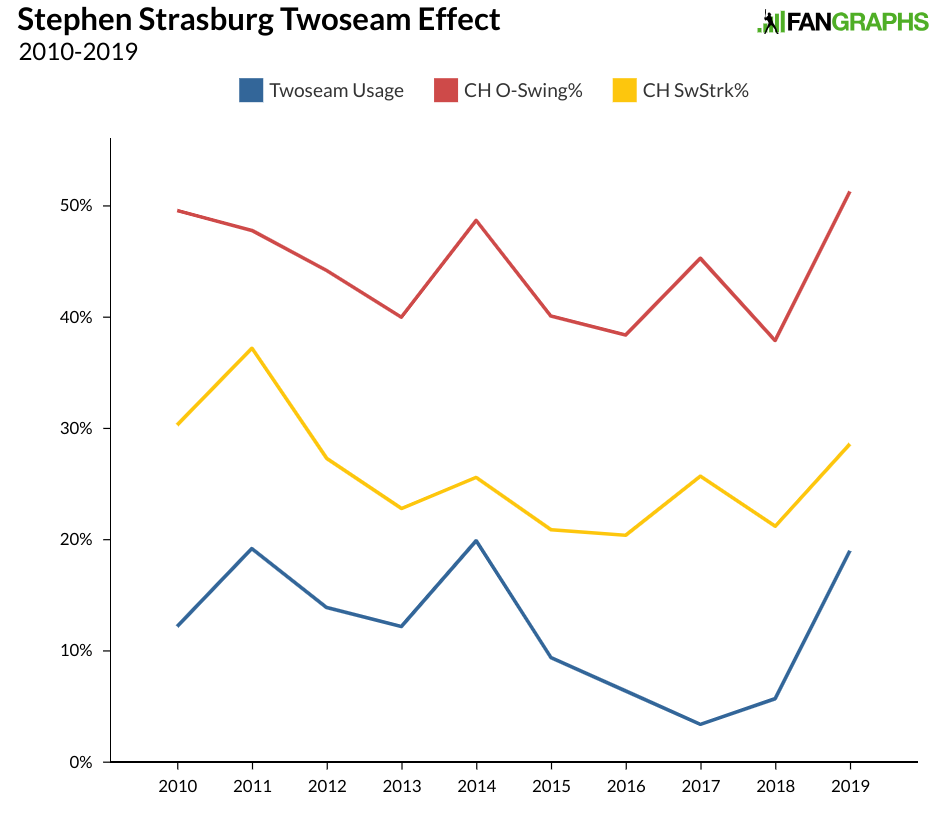

The other aspect of the fastball switch is Strasburg’s changeup. Last season, Strasburg’s change was still very good, but hitters chased the pitch out of the zone 38% of the time, which was the lowest figure in his career. Strasburg throws the pitch in the strike zone less than 30% of the time, so the utility of the pitch is considerably less if hitters don’t swing outside the zone. To fool batters, it might be helpful to throw another pitch that looks like a changeup but is definitely not a changeup. Enter the two-seamer. To get a sense of how the two-seamer might help get swings on the change, let’s take a look at the movement on Strasburg’s offerings, from the viewpoint of the catcher.

First, we can see why the four-seamer and curve make a good pair. They move in completely opposite directions at different speeds. A pitcher can throw the fastball at the top of the zone on the inside corner, and then follow up with a curveball in the exact same manner and end up with a pitch on the lower outside corner. Changing speed, levels, and sides of plate while throwing to the exact same spot is disorienting. Also apparent is how a well-thrown changeup after a good two-seamer can fool batters. The changeup comes up a bit slower and several inches lower, but looks like the exact same pitch to the batter.

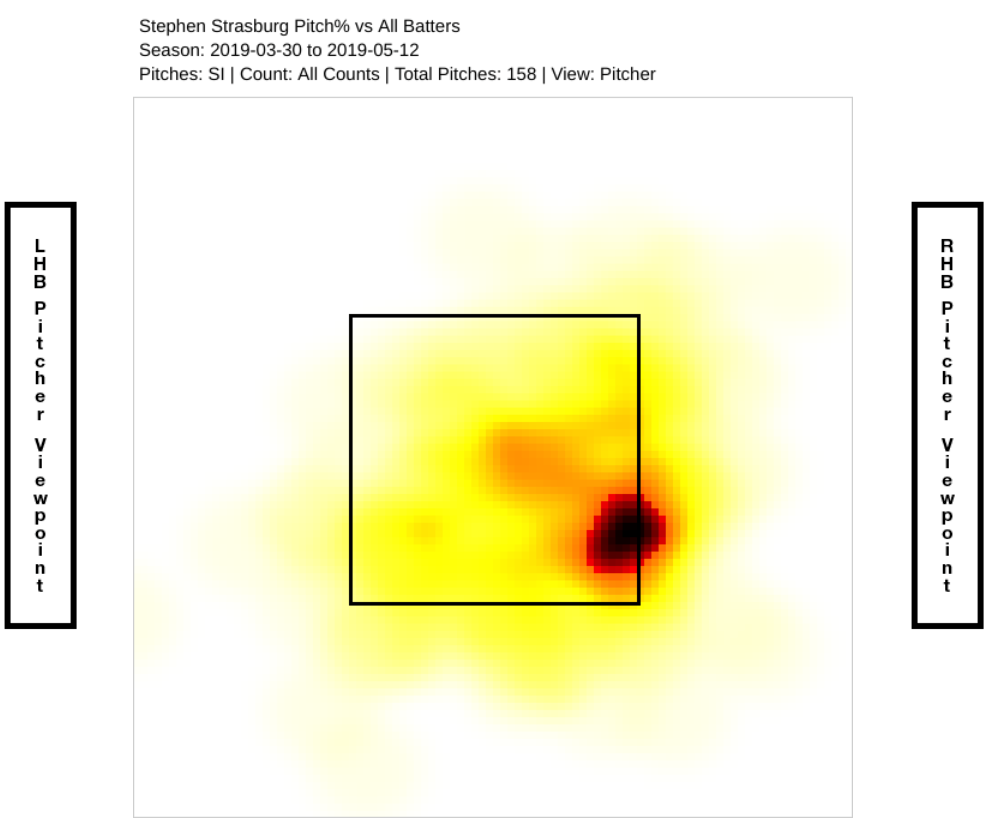

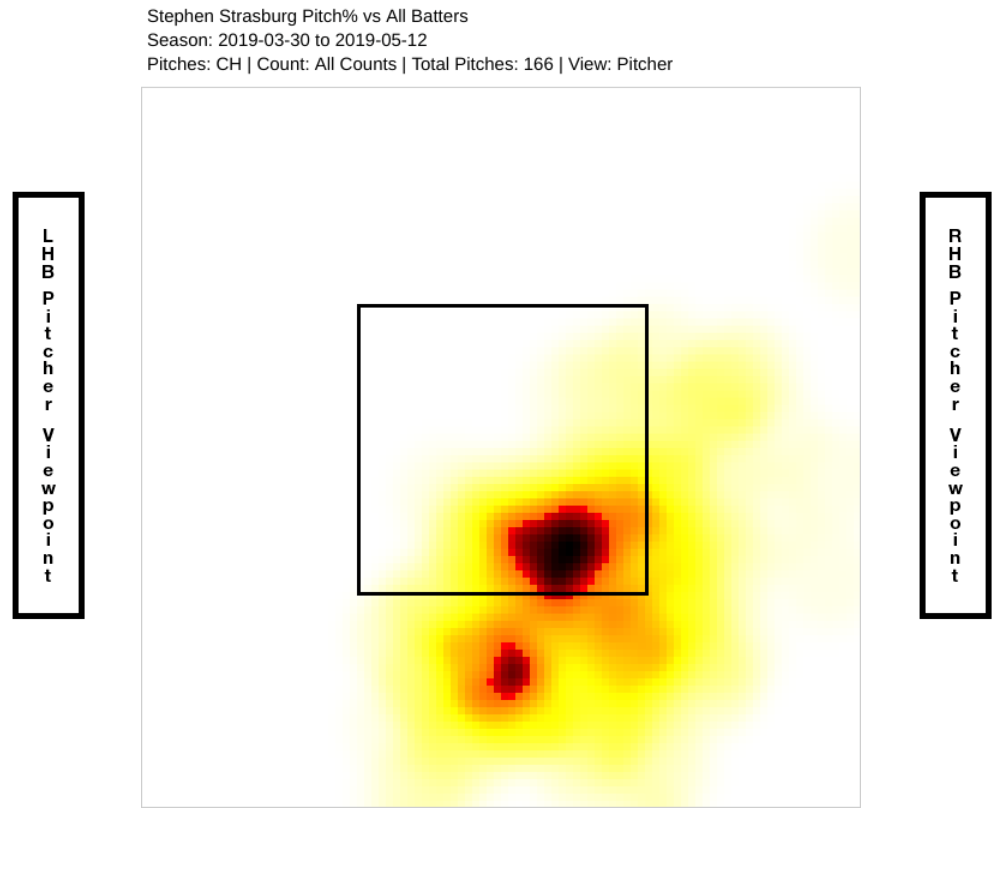

This is where Strasburg has thrown his two-seamers this season.

This is where Strasburg has thrown his changeups.

He’s got a few pockets where he throws the sinkers, and then similar pockets lower for his change. Here’s how those pitches worked against Eric Thames. First, a sinker.

A few pitches later, here’s the change.

He’s still throwing the change well below the zone and getting whiffs on it like he always has, as well.

When a pitcher throws multiple pitches over many years and is simultaneously going through the aging process with diminished velocity, it’s hard to say whether some differences are working. In a vacuum, the Strasburg sinkers are bad because he is getting poor outcomes. On the other hand, he’s pitching as well as he ever has with diminished velocity and he’s throwing the two-seamer more often. For some further support of the usage change, here’s a graph matching up two-seamer usage and some plate discipline numbers on the change during Strasburg’s career.

In basically every year but 2017, we can match increased or decreased usage of the two-seamer with the effectiveness of the change. It’s hard to know for sure if the trade-off is worth it. Strasburg’s change is better this year and his four-seamer seems to have benefited from being thrown less often as well. Last season, Strasburg threw 1100 total fastballs and was -7.2 runs on those pitches. This season, he’s thrown about 40% as many fastballs, and he’s 2.4 runs above average so far on those pitches. He’s also doing much better with his curves with the increased usage, as the pitch has been as good or better than at any point in his career. Stephen Strasburg is changing in a way most pitchers nowadays aren’t. It’s hard to tell for sure if his changes are causing better results than he got last year, but at this point, hitters haven’t provided many reasons for Strasburg to go back to the slightly successful pitcher he was in 2018, when he’s been a very successful pitcher so far this season.

Craig Edwards can be found on twitter @craigjedwards.

Interesting piece. I wonder if in another generation if we’ll see the sinker come back after everyone adjusts from being low ball hitters to high ball hitters.

Its all cyclical. If you go back to the 60’s and 70’s when umps were calling a taller strikezone, pitchers were able to use it to great effect. Fast forward to the 80’s and 90’s when the strikezone was reeled in a bit, and every pitching coach was preaching about living down in the zone. Today, hitters are moving away from the flat level swing method that was preached to me by my little league coach, and batters are just killing the low ball. There are definite advantages to be ahead of the trends. Mike Trout is Mike Trout. But he definitely feasted on low pitches early in his career before GMs and teams started realizing that philosophy didn’t work against his swing.