Syndergaard Signing Bolsters Dodgers’ Rotation, Hurler’s Own Hopes for Rebound

Despite trailing only the Mets in payroll last season, the Dodgers inked just their second eight-figure contract of the offseason Wednesday night. Noah Syndergaard and his one-year, $13 million pact will join the returning Clayton Kershaw (on a one-year, $20 million deal) in shoring up a rotation that has said goodbye to breakouts Tyler Anderson and Andrew Heaney.

Enduring the losses of Anderson and Heaney means the Dodgers will have to rely more heavily on a number of pitchers with health concerns. Julio Urías, whose 2.16 ERA came out just above Tony Gonsolin’s 2.14 mark, is the only Dodgers starter to have thrown at least 175 innings in each of the past two years; Urías was himself a non-factor for two years after having anterior capsule surgery on his left shoulder in 2017. As for Gonsolin, owner of the rotation’s lowest 2022 ERA, he suffered a forearm strain in late August; he would go on to pitch just 3.1 innings the rest of the year, including the playoffs. Relegated to mid-rotation duty now, Kershaw hasn’t appeared in 30 games since 2015 and in the past two seasons hasn’t topped 22. Dustin May, Tommy John returnee, was only in the rotation for six turns this summer before landing on the shelf again, this time with a back issue. And now the player formerly known as Thor will round things out.

After bursting onto the scene as a young flamethrower in 2015 and notching an All-Star nod the next season, Syndergaard missed almost all of ’17 with a partially torn lat. The next year, he missed time with a ligament issue in his right index finger. After a career-high 197.2 innings in 2019, he went under the knife for Tommy John and missed nearly all of ’20 and ’21 due to setbacks. Upon returning, he managed 134.2 innings despite the Angels’ six-man rotation and a brief move to the Phillies’ bullpen in September. But the big Syndergaard story this year was his velocity dip.

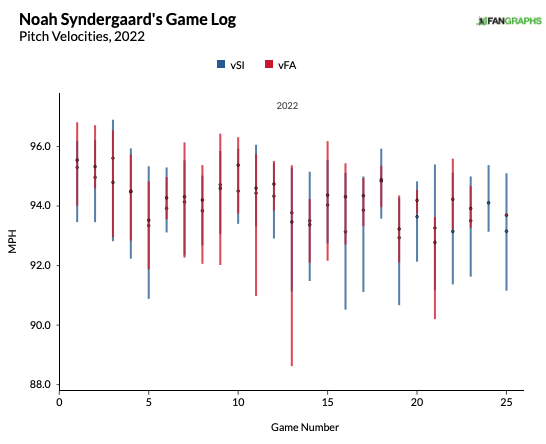

Aside from his flowing blonde locks, young Syndergaard was best known for his ability to routinely hit 100 mph with his fastball. From 2015-19, he touched triple digits 254 times, more than any other starter and behind only six relievers. This season, his four-seamer topped out at 96.4 and showed no signs of recovering throughout the year:

I included the sinker in this graph because it became his primary fastball down the stretch. The Phillies, owners of the highest sinker percentage in the majors last year, likely identified Syndergaard and his diminished velocity as a prime target for inclusion in their system: in an August 16 update, just after the Phillies acquired him, wpStuff+ (which looks at pitch shape and velocity relative to the league average for that pitch type) pegged his four-seamer as 44.5% below average and his sinker 3.9% above. After moving to Philadelphia, Syndergaard’s sinker usage soared:

| Team | FA | SI | SL | CU | CH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angels | 20.9 | 26.2 | 20.1 | 9.5 | 23.2 |

| Phillies | 5.4 | 40.3 | 26.0 | 13.0 | 15.3 |

The pitch grew even more effective with increased usage, going from saving 3.34 runs per 100 throws with the Angels to saving 4.40 with the Phillies. He also leaned more on his slider, a typical sinker pairing. It too improved, going from costing 0.49 runs per 100 to saving 0.1. But despite their high propensity for sinkers, the Phillies actually ranked 27th in slider usage. Why did they make an exception for Syndergaard’s? And why did the move work?

His sinker and slider don’t mirror each other well in terms of spin, as their three hour, 15 minute differential is far from the six hour ideal. The slider, previously Syndergaard’s whiffiest pitch with a 20.6% swinging-strike rate on his career, only got whiffs on 8.6% of tosses this year. While his pitches all whiffed below his career norms, the slider’s drop in swinging-strike rate was the largest. The move to a less-whiffy primary fastball didn’t help, but the single-most prominent reason for his dip in strikeout rate (to 16.8%, far below his career 24.8% mark), was the slider’s inability to generate swings and misses. Meanwhile, his curve not only mirrors his sinker better — with a four hour, 45 minute differential — but it had the highest swinging strike rate of his arsenal at 15%. The Phillies upped its usage too, but not as much. Why?

It’s important to note that when a hurler loses velocity, they don’t do so uniformly across their pitches. After a drop in velocity, pitchers will typically adjust their repertoire, moving away from the fastball and relying more heavily on their other offerings. Which other offerings they lean on depends in part on how the velocity loss is distributed. Certain pitches are more dependent on velocity; others, on velocity gaps. Eno Sarris at The Athletic has done work on this, and he has concluded that sliders that don’t mirror fastballs well should have larger velocity gaps to compensate. Syndergaard’s whirly certainly falls in the poor-mirroring category, and this season its velocity gap has only grown:

| Year | SL | CU | CH |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 8.8 | 17.2 | 5.1 |

| Career | 7.4 | 16.0 | 7.1 |

Sarris also notes that straight changeups, like Syndergaard’s (which has just 3% less drop and 8% more run than average), rely on velocity gaps to be effective too. The changeup slowed down the least out of Syndergaard’s offerings, narrowing the gap between it and his sinker. At the same time, while the curveball has also seen an increase in velocity gap, the gain is smaller overall and percentage wise. Plus, Sarris indicates that overall velocity may be more important for a curve relative to velocity gap than it is for a slider.

Unless you’re trading it for more movement, which Syndergaard is not, it’s never a good thing to lose velocity. That being said, there are adjustments a pitcher can make to blunt the impact of such a loss. Four-seamers, heavily reliant on their speed for success, are the first pitches to be shirked. But there is no easy answer when cobbling together the rest of a pitcher’s repertoire; for the other offerings, it depends on the magnitude of velocity loss, how important velocity is to the pitch, and the new gap between its speed and the primary fastball’s.

The Phillies seemed well on their way to picking up the pieces for Syndergaard; after they acquired him, his average exit velocity, max exit velocity, barrel rate, and hard-hit rate all dropped. The thing is, the Phillies ranked second-to-last in team OAA last season and the increased usage of Syndergaard’s whiff-less sinker/slider combo meant he was pitching to contact for the club. Though his control, which often comes back last for Tommy John recipients, remained impeccable, whatever weak contact he generated through pinpoint location all too often sailed beyond outstretched Phillies’ arms; he ran a BABIP .43 points higher with the Phillies than he did for the Angels. The Dodgers, on the other hand, ranked ninth in OAA last season, but will have the tall task of replacing Trea Turner (who swapped places with Syndergaard en route to Philadelphia) and Gold Glover Cody Bellinger (who left for the Cubs). Third base stalwart Justin Turner also remains a free agent. At the same time, the Dodgers still have Gold Glovers Freddie Freeman and Mookie Betts at first and in right field, plus a more pitcher friendly venue than Citizens Bank Park; our five-year park factors gave CBP a 101, meaning slightly hitter friendly, while Dodger Stadium notched a 98 (slightly pitcher friendly).

Given the fragility of their pitching corps and their win-now tendencies, the Dodgers are counting on Syndergaard to be a productive regular in 2023. But that’s all; they would be hard-pressed to bet on another injury-prone arm in the long-term. Plus, with enticing prospects Bobby Miller and Gavin Stone on the way, not to mention the eventual return of Walker Buehler, they might not need Syndergaard for much longer. And with an opportunity to avoid paying a consecutive-seasons luxury tax penalty, the bargain makes for a perfect marriage. For Syndergaard’s part, he was once lining up for a big payday and still believes he can get one. With one season of diminished-velocity craft-honing under his belt, this one-year contract might be all he needs to make a bigger splash as a free agent next year.

Alex is a FanGraphs contributor. His work has also appeared at Pinstripe Alley, Pitcher List, and Sports Info Solutions. He is especially interested in how and why players make decisions, something he struggles with in daily life. You can find him on Twitter @Mind_OverBatter.

Having a player development program that helps resuscitates the careers of 31-year old pitchers is an incredible market inefficiency. If you can pick up guys with interesting stuff and turn them into good players, that’s a huge win.

A less important part of that, but arguably more interesting, is the second-order effect it has on finding top-flight candidates for that development program. Think about this: Noah Syndergaard, who used to sit 98 as a four-win pitcher, signed with the Dodgers for $13M plus incentives. Michael Lorenzen, who had his best year as a reliever in in 2019 and has only started 44 games in his 8 year career, got signed to an $8.5M deal plus roughly the same incentive amounts to compete for a rotation spot. I know which one I’d rather have at those prices: Syndergaard put up only 2.2 fWAR last year, but Lorenzen has only put up 4.3 cumulatively over his career.

How much do you think the Tigers would have had to offer to beat the Dodgers’ offer? I’m guessing it would have to be at least twice as much and possibly much more, because the Tigers don’t have the track record of fixing broken starters and helping to turn around pitchers’ careers like the Dodgers do.

Other than SF, who else has a similar reputation?

The Rays?

I can’t think of anybody else turning that trick repeatedly.

Pittsburg did it but that was a while back.

Rangers, funnily enough. Mike Minor, Lance Lynn, Kyle Gibson, and Martin Perez in consecutive years.

Ah, yes.

I knew I was missing somebody.

Astros.