Tarik Skubal Seems To Have Solved His Biggest Issue

The Detroit Tigers entered this season with plenty of reason to be hopeful for a shift in the franchise’s fortunes. After a stretch of four straight playoff appearances from 2011–14, they entered a long rebuilding phase that included an ugly, 114-loss season in ‘19. Last year, they showed real signs of progress; after winning just eight games in April, they went 69-66 through the rest of the season and graduated a bunch of their top pitching prospects into the majors. They had an aggressive offseason, signing Javier Báez and Eduardo Rodriguez and trading for Austin Meadows, and were set to debut their top position player prospects, too.

Things haven’t gone according to plan so far. The Tigers currently have the worst record in the American League and a big reason why is the disappointing performances of their young starting pitchers. Both Casey Mize and Matt Manning have been sidelined with injuries, and Beau Brieske and Joey Wentz have stumbled through tough big league debuts:

| Player | FV (Prospect Rank) | IP | K/BB | ERA | FIP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matt Manning | 60 (2nd, 18th overall, 2021) | 93.1 | 1.85 | 5.50 | 4.55 |

| Tarik Skubal | 60 (3rd, 22nd overall, 2021) | 221 | 3.73 | 4.19 | 4.64 |

| Casey Mize | 55 (4th, 32nd overall, 2021) | 188.2 | 2.64 | 4.29 | 4.95 |

| Joey Wentz | 45 (8th in org, 2022) | 2.2 | 0.50 | 20.25 | 4.59 |

| Beau Brieske | 40+ (10th in org, 2022) | 26.1 | 1.36 | 5.13 | 6.66 |

| Alex Faedo | 40 (16th in org, 2022) | 15.2 | 3.00 | 2.87 | 3.99 |

It’s far too early to make definitive statements about any of these young pitchers, but their struggles have definitely put a damper on the Tigers’ aim to break out of their rebuilding cycle this year. If there’s one reason for fans in Detroit to be encouraged, though, it’s the early season success of Tarik Skubal.

After struggling through his first season in the majors during the shortened 2020 season, Skubal had an up-and-down year in ‘21. With a batted ball profile that featured plenty of elevated contact, he suffered from a big home run problem through his first two seasons in the big leagues. Among all qualified starting pitchers in 2020 and ‘21, his 20.4% home-run-per-fly-ball rate is tied with Patrick Corbin and JT Brubaker for the highest in the majors, and the 44 home runs he allowed was the fourth highest mark during that two year period. All those dingers pushed his ERA and FIP up to 4.57 and 5.20, respectively. To have any sustained success in the majors, he desperately needed to figure out how to reduce the number of balls flying out of the yard.

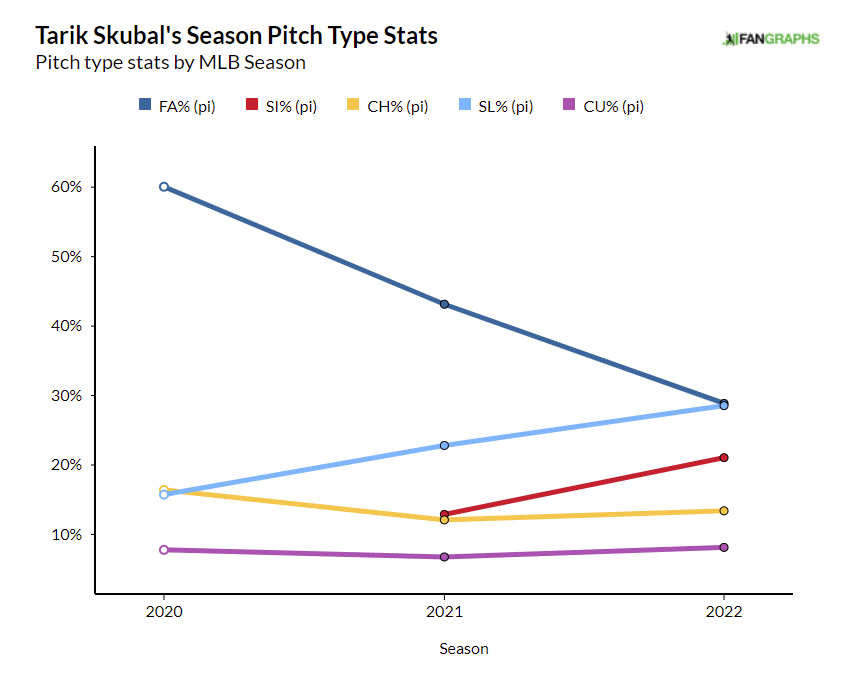

Through seven starts this year, it appears as though Skubal has figured out how to do just that. He’s allowed just two home runs in 2022 and both of them came in the same game against the Astros on May 5. He opened the season with four straight homerless starts, the longest such streak of his career. The biggest difference-maker in the early going has been his pitch mix:

Last year, Skubal allowed 22 home runs off his four-seam fastball alone. The obvious answer to his dinger problem would be to simply throw the pitch opposing batters are blasting far less often, and that’s exactly what he’s done. He’s cut the usage of his four-seamer down to just 28.9%, with his slider and sinker making up the difference. What’s even more encouraging is that the two home runs he’s allowed this year have come off other pitches in his arsenal; he’s actually inducing a ton of weak contact with his heater this year.

| Years | BBE | GB% | FB% | Hard Hit% | xwOBAcon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020-21 | 222 | 26.6% | 46.4% | 50.5% | 0.513 |

| 2022 | 24 | 41.7% | 37.5% | 33.3% | 0.238 |

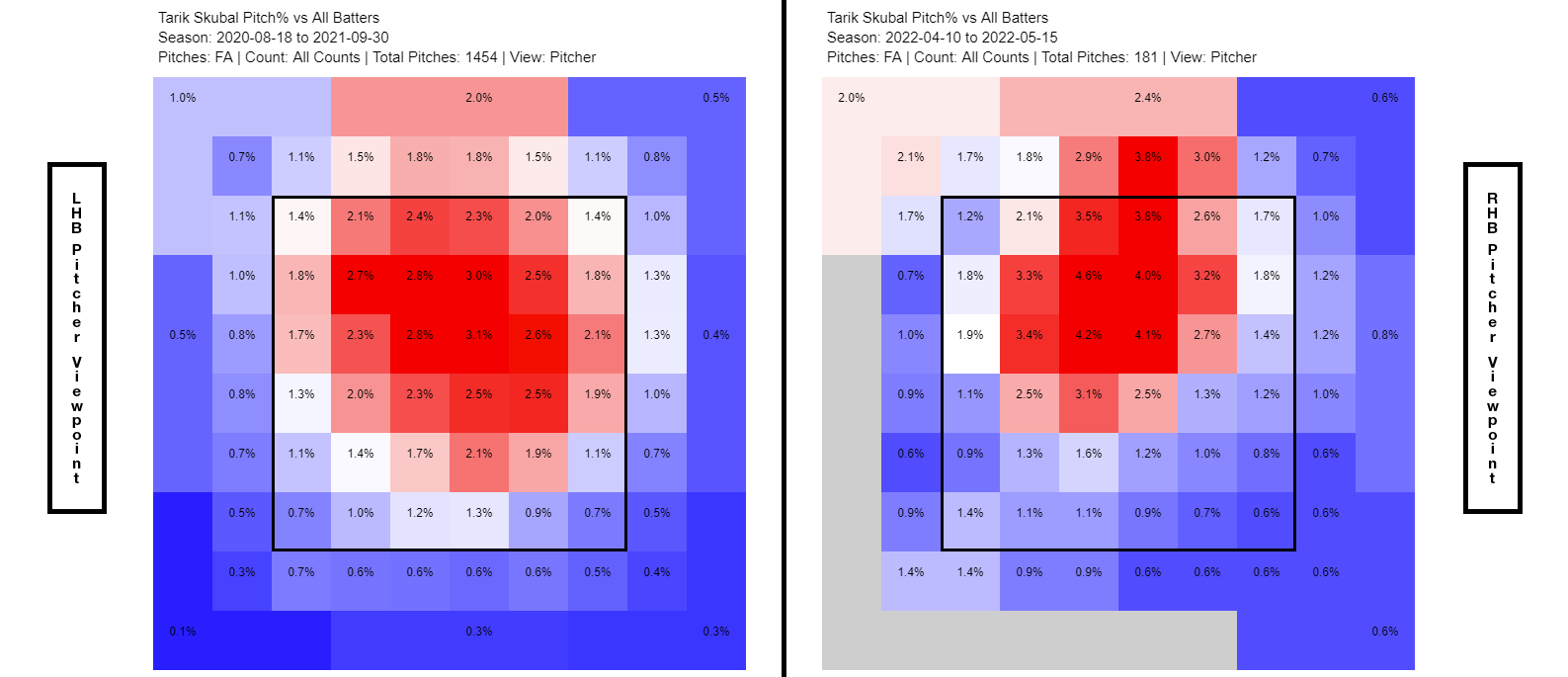

During his first two years in the majors, opposing batters feasted on his fastball; more than half of the balls put in play off the pitch were hard hit and he allowed a .513 expected wOBA on contact, the eighth highest mark for a four-seam fastball with at least 50 batted ball events during the two year period. Those two marks have improved by leaps and bounds this year, though we’re talking about just 24 batted ball events. The shape of the pitch isn’t any different, but Skubal is locating it in more favorable areas of the zone:

On the left are his fastball locations from 2020–21, with this season on the right. During the first two years of his big-league career, Skubal grooved far too many fastballs down the heart of the zone. It’s no surprise batters were able to crush the pitch with that kind of poor command. This year, he’s elevating his fastball in the upper third of the strike zone and above with regularity. That has helped him maintain the pitch’s excellent swinging strike rate while also allowing him to induce weaker contact with the pitch.

By reducing the use of his heater, he’s also forcing batters to complicate their decision-making process, as they have to account for his secondary weapons more. Throwing his slider and sinker more often has helped him improve his batted ball mix, too. Both of those pitches generate groundball contact at an above-average rate. The result has been an overall groundball rate that’s jumped to 48.1% this season, up from 38.5% last year. Keeping the ball out of the air is another surefire way to keep the number of home runs he’s allowed down.

Of course, the deadened baseball has also likely helped him keep the ball in the yard, but Skubal has shown some improvements in reducing the contact quality he’s allowing. His barrel rate has fallen from 13.9% last year to just 5.7% in 2022, and just 35.8% of the balls in play off of him have been hard hit. Of the six barrels he’s allowed this year, two have flown over the fence. Even in this depressed offensive environment, that rate is well below league average. (Barrels have turned into home runs around 50% of the time prior to this year; with the deadened ball, they’re flying over the fence around 43% of the time this season.) Yes, Skubal has benefitted from the soggy ball, but many of the improvements he’s made to his approach — his groundball rate in particular — would have reduced the number of home runs allowed anyway.

The improvements to Skubal’s pitch arsenal go beyond an optimized pitch mix; his changeup has greatly improved this year as well. Last April, he toyed with adding a splitter to his arsenal — a pitch he had learned from Mize — but limped to an ERA over six during the first month of the season. He ditched the split and went back to his changeup and enjoyed a bit of success with it through the rest of the season. As Michael Ajeto detailed in January for Baseball Prospectus, Skubal’s changeup is one of his best weapons and it shared a bunch of characteristics with Lucas Giolito’s change. Ajeto wrote:

“[Skubal doesn’t throw] your quintessential changeup. Located up in the zone, it just kind of moves through space, not sinking much, and not running much, either. That makes for two reasons. First is that it’s thrown up in the zone which, until recently, was considered sacrilege. But also, generally speaking, the point of a changeup is inherent in its name. If Skubal is just throwing a slower version of his fastball but otherwise not separating vertically or horizontally, how has it racked up so many strikes?”

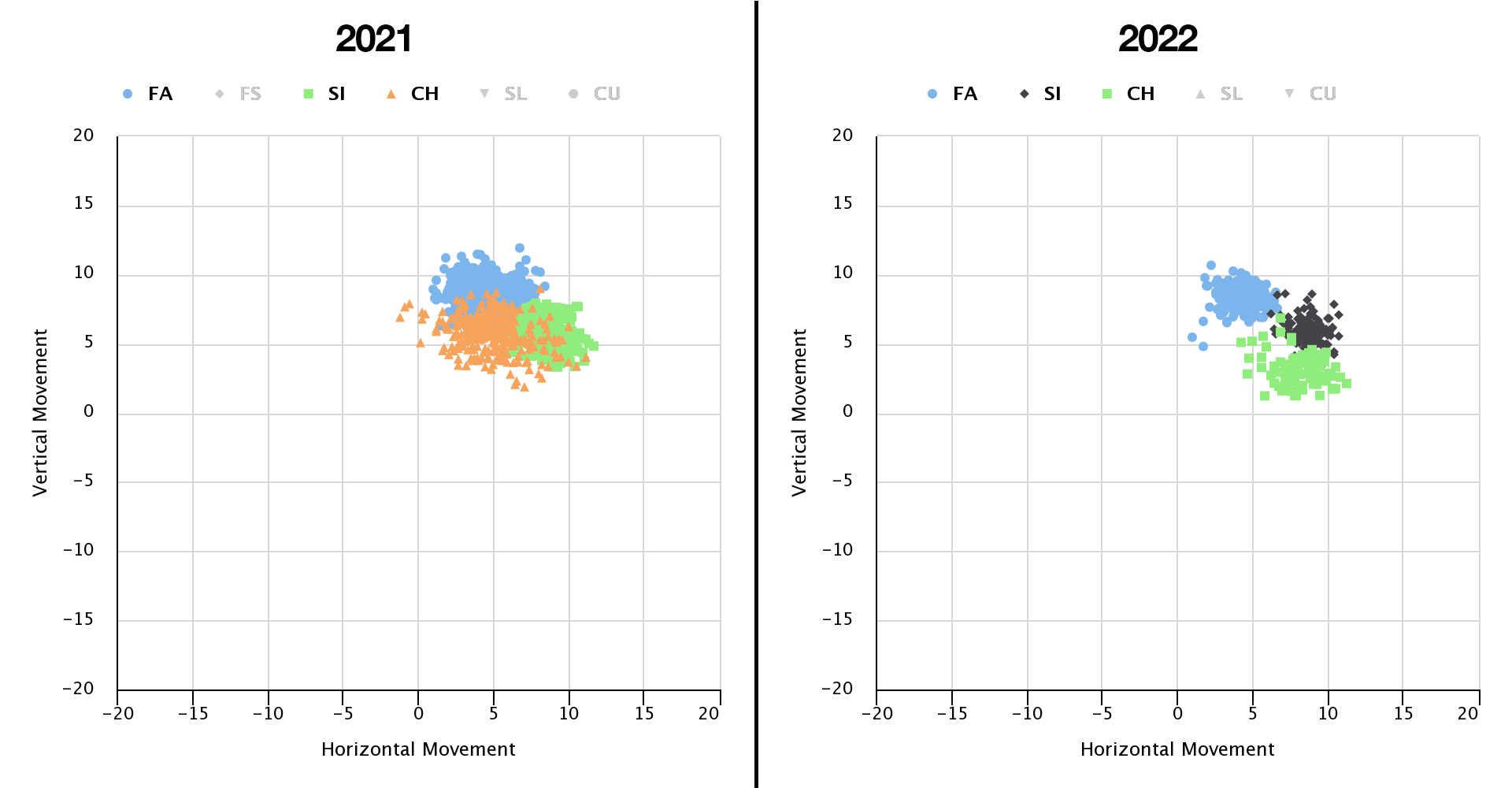

Giolito has found a ton of success throwing his elevated straight changeup, and Skubal followed that same blueprint last year. This season, his changeup looks nearly unrecognizable, featuring a completely revamped shape:

| Year | Velocity | V Mov | H Mov | Active Spin | Spin Axis | Spin Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 82.1 | 28.5 | 8.7 | 98.0% | 10:45 | 0 |

| 2022 | 83.6 | 32.0 | 14.5 | 83.0% | 10:30 | 45 |

Skubal has added three and a half inches of drop and nearly six inches of arm-side run to his changeup. It’s gone from a straight change to a pitch that has considerable fade. All that additional movement with only a slight drop in active spin and a ton of new spin deviation likely means the pitch is enjoying the effects of seam-shifted wake. With an already-elite 10 mph velocity differential between his fastball and changeup, all that added movement and deception make it one of the most effective changeups in baseball.

Here’s what this revamped changeup looks like in practice:

The camera angle at Comerica Park doesn’t do the pitch justice — you really can’t see much of the arm-side action at all. Here’s another example with a much better camera angle:

You can clearly see the drop and fade the pitch now features. Opposing batters have whiffed 45% of the time they offer at the pitch and have produced just a .228 expected wOBA on contact when they manage to put wood on it. Both marks are among the best for any changeup thrown at least 50 times this year. He’s also inducing more groundball contact with the pitch, helping reduce the number of home runs he allows even more.

What’s even more interesting is how his new changeup interacts with the rest of his arsenal. His older straight changeup was clearly designed to play off his four-seam fastball. The movement profile and spin axis all indicate a desire to mirror the shape of his heater, with the velocity differential carrying the load of deceiving the batter. With more drop and run, his new changeup suddenly mirrors the shape and spin axis of his sinker:

| Pitch Type | Velocity | V Mov | H Mov | Inferred Spin Axis | Observed Spin Axis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | |||||

| Four-seam | 94.3 | 14.8 | 8.3 | 10:45 | 11:00 |

| Sinker | 94.5 | 19.1 | 15.1 | 10:45 | 10:15 |

| Changeup | 82.1 | 28.5 | 8.7 | 10:45 | 10:45 |

| 2022 | |||||

| Four-seam | 93.9 | 15.1 | 7.8 | 10:45 | 11:00 |

| Sinker | 94.5 | 18.8 | 15.5 | 10:45 | 10:15 |

| Changeup | 83.6 | 32.0 | 14.5 | 10:30 | 9:45 |

Each of these three pitches start with the same inferred spin axis but diverge greatly once they reach the plate. The new movement profile and spin deviation of his changeup fits his sinker like a glove. Here’s a visual comparison of the shape of his fastballs and changeup over the last two years.

Because Skubal is relying on his four-seamer less often, the need to play his changeup off that pitch has lessened. And because he’s throwing his sinker a bit more often, adjusting his changeup to mirror that pitch seems like a prudent move.

Skubal’s current 5.4% home-run-per-fly-ball rate won’t last — it’s bound to regress towards league average at some point this season. But even with a league average home run rate, he’d still be in the middle of a breakout season; his xFIP is a fantastic 2.71. The adjustments he’s made to his pitch mix, fastball location, and changeup shape have all contributed to a vastly improved approach to opposing batters. Without all those home runs holding him back, his elite strikeout-to-walk ratio has been allowed to shine, leading to a breakout campaign in 2022. That’s very good news for the future of the Tigers starting rotation.

Jake Mailhot is a contributor to FanGraphs. A long-suffering Mariners fan, he also writes about them for Lookout Landing. Follow him on BlueSky @jakemailhot.

it also seems like the change-up pairs nicely with the slider, has the same vertical movement and about the same horizontal movement but in different directions.