The 2023 Rule Changes Are Here, and They’re All Good

After more than a century of a deistic laissez-faire attitude toward the sport, Major League Baseball made a remarkable announcement on Friday: Next year, for the first time, baseball will have a clock. The introduction of a pitch clock at the highest level of the game is merely one gourd in a cornucopia of rule changes approved late last week by the league’s competition committee, but it could revolutionize the sport. You can find the full list here, but rather than delve into the minutiae, I want to give a brief précis of the most important highlights and deliver a remarkable conclusion.

Bigger Bases

- The bases will increase in size from 15 inches square to 18 inches square.

Banning the Shift

- All four infielders must have both feet entirely on the infield dirt when the pitcher is on the rubber.

- Two infielders must be entirely on either side of second base.

- Failure to comply will result in an automatic ball.

Pitch Clock

- Once the ball is ready for play, the pitcher must begin his motion within 15 seconds with the bases empty, and 20 seconds if there’s a runner on.

- The batter must be in the box “alert to the pitcher” within eight seconds of the timer starting.

- If the pitcher is late, he’s charged with an automatic ball. If the batter is late, he’s charged with an automatic strike.

- The pitcher may “disengage” from the rubber (i.e. step off or throw to the bases) no more than twice per plate appearance. If the batter advances during the plate appearance, the disengagement counter is reset. If the pitcher steps off or throws to the bases a third time, the runner automatically advances if the pickoff attempt is unsuccessful.

- In order to speed up play generally, there will be a 30-second limit on both mound visits and the time between batters.

These changes weren’t unanimous — the four players on the competition committee voted not to ban the shift or implement a pitch clock — but they’re extremely good. Seriously. After years of expanding the playoffs, contracting minor league teams, trying to implement an international draft, and other such (at best) controversial proposals, MLB gets an A for the 2023 rule changes. Take it home, show it to your parents, have them stick it on the fridge.

Okay, I have two minor objections. The first is that in addition to increasing the size of the bases, I would’ve liked to see a slow-pitch softball-style double first base implemented in order to reduce collisions and encourage batter-runners to run in foul territory. The second is that among the time-saving measures coming for 2023, batter walk-up music will be limited to 10 seconds. That’s a blow for anyone who grew up dreaming of entering to Meat Loaf’s “Bat Out of Hell,” but even so, there’s no shortage of songs that suit a 10-second excerpt: Tame Impala’s “Elephant,” John Denver’s “Thank God I’m a Country Boy,” and various motifs from Sergei Prokofiev’s “Peter and the Wolf,” just to name three.

We can work with this. So let’s go through the three big-ticket items, in increasing order of importance.

18-Inch Bases

This change is going to be imperceptible to fans, but represents a few potential positives without much of a downside. Anyone who knows their way around a pizza menu will tell you that a small increase in perimeter represents a giant increase in surface area — about a 45% increase, by my math. That won’t eliminate dangerous tie-ups between fielders and runners, but every additional square inch helps. Spikings, trippings, twisted ankles — these are some of baseball’s most painful and least necessary injuries, and bigger bases give players just that much more real estate to fight over.

Increasing the size of the bases also shortens the distance between bases by 4.5 inches, and gives runners a larger target to aim at as they try to avoid tags. Will this result in a perceptible increase in basestealing? Probably not — we all remember bang-bang plays that get decided by margins of less than five inches, but they don’t happen every night. A Baseball America study of data from the Triple-A trial of 18-inch bases revealed no perceptible effect on the offensive environment. Still, it’s hard to see a competitive downside to a measure that ought to reduce the risk of injury.

The Shift

The debate over whether the shift is good for baseball has been going on so long I remember writing a blog post in 2009 about how Ryan Howard should learn to drag bunt so opponents couldn’t overload the right side of the field against him. (Almost as contentious? The exact circumstances under which the shift works best.) This has been a long time coming.

In a perfect world, MLB wouldn’t have had to ban the shift. Players would have changed their approach and started flicking the ball the other way. Failing that, teams would recognize the competitive advantage of spray hitting and scouted and developed hitters who can use the whole field. Joe Sheehan put it quite well on Twitter last week: “Shift restrictions don’t reward contact, they reward dead-pull hitting.”

But that much-prophesied generation of Zoomer Tony Gwynns never showed up, and after 10 or 15 years of hand-wringing, the list of most-shifted players in baseball just looks like a list of the best hitters in baseball. No, seriously. The top five hitters in plate appearances against the shift this season — Corey Seager, Marcus Semien, Freddie Freeman, José Ramírez, and Matt Olson — have all signed nine-figure contracts in the past 12 months. Cedric Mullins and Rafael Devers are in the top 10, and Juan Soto and Shohei Ohtani are in the top 15.

Rather than work around the shift, the top left-handed hitters in baseball have for the most part decided that the best option is to swing like hell and live with the occasional 115 mph lineout to a second baseman standing in short right field. Immediately after decrying the new shift rule, Sheehan diagnosed the real problem: It’s too hard to hit the ball. Even if most hitters were able to dink and dunk the ball to a specific place like Carlos Alcaraz — which they aren’t — contact is too precious a commodity to waste on anything but full-effort swings.

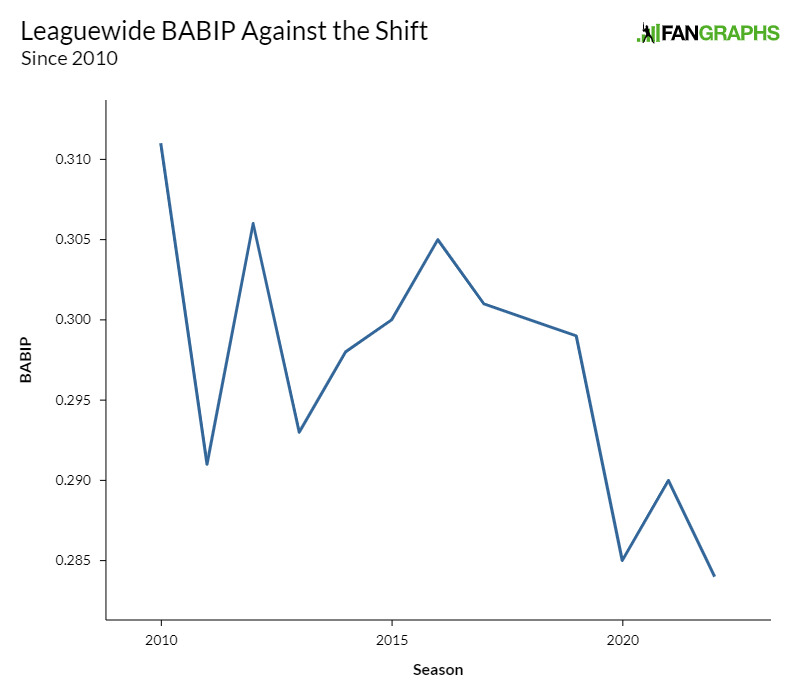

And the shift is only getting better at eating up batted balls:

MLB could goose the league-wide BABIP by moving the mound back, or transitioning to a smooth baseball, or gently electrocuting any pitcher who throws harder than 94 mph. But failing that, it’s time to concede defeat. We’ve waited more than 10 years, and the spray hitting/drag bunting revolution just hasn’t come, and probably never will. Treating the symptoms isn’t as good as curing the disease, but it’s better than not treating the symptoms at all.

The new rules don’t preclude the shift so much as they handcuff it. The aforementioned BA study showed that the new defensive positioning rules had little effect, if any, on the aggregate league-wide BABIP, but it’s fair to say that restricting the shift will influence which batted balls turn into hits. Teams can still overload one side of the infield in practice — does anyone doubt Francisco Lindor can get from just left of second base to a position in short right center in time to cut off a groundball? And against the likes of Ohtani, Joey Gallo, and Oneil Cruz, infielders will line up right at the edge of the grass, if only to reduce the possibility of having a line drive knock their teeth out via the cerebellum. Defenders can still run out in creative formations, but like poets bound by the structure of a villanelle, they’ll have to get even more creative than they are now in order to work within the restrictions.

Now, if MLB wanted to get really wacky, it would increase the minor latitude teams already have in where the infield boundary gets placed. What if all four infielders had to stand on the dirt, but the dirt could be the shape of a teardrop, or a fried egg, or the island of New Guinea? What if the Astros could festoon the Minute Maid Park outfield with bunkers, like a golf course, in order to facilitate the shift and the four-man outfield?

Too much?

The Pitch Clock

MLB’s new timing restrictions could end up being the most significant rule changes of the past 50 years. If properly enforced, they will at the very least alleviate the biggest problem with modern baseball as a spectator sport. At best, they’ll alleviate the baseball’s three or four biggest problems as a spectator sport. Follow along and stop me when I come to a predicted effect of this rule change that doesn’t sound like it would make the game noticeably better overnight.

For the past few years, MLB has tended to address its pace of play problem in terms of length of game. Even the MLB.com article referenced above addressed the most common question: How much will it shorten games? The answer, according to minor league data, is about 26 minutes, which is a huge number.

We’ve all seen well-paced three-hour movies, and riveting four-and-a-half-hour baseball games. It’d be nice to have a World Series game end before the kids have to go to bed, and for the beat writers to make it to the bar before last call, but… here, I’ll quote Bill James in the New Historical Baseball Abstract:

“The problem with long baseball games isn’t the time they take. The problem is that the wasted time inside baseball games dissipates tension, and thus makes the games less interesting, less exciting, and less fun to watch.”

That essay was published in 2001, when the average major league game was nine minutes shorter than it is now. James argued for prohibitions on pickoff throws similar to the rule MLB is set to adopt, but specifically objected to the idea of a pitch clock.

Here’s what’s happened since:

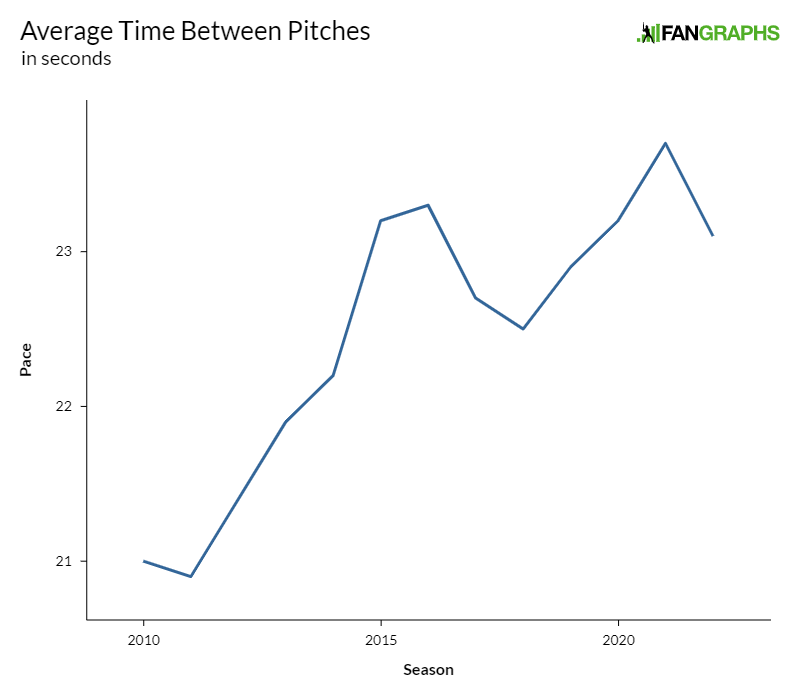

In 2010, the average time between pitches was an even 21 seconds. By 2021, it was 23.7 seconds, which has come down a bit this year thanks to PitchCom but is still almost 10% higher than it was a decade ago. The FanGraphs glossary page on the Pace stat, written in 2015, comes with a handy chart: 21.5 seconds is average, 23.5 seconds is slow. The entire league, by those standards, is positively Trachselite in its tempo.

Relievers, whose share of the game increases each season, topped out at 24.7 seconds between pitches last year. Giovanny Gallegos, may God have mercy on his soul, is the slowest among pitchers with 10 or more innings, at a pace of 31 seconds in all situations. It’s just not necessary.

Those few seconds per pitch bleed the energy out of the game a few drops at a time, and oh by the way add up to playoff games glopping on past four hours and ending after midnight on the East Coast. They’re the difference between a game that drags like the hymns at an Episcopalian funeral and a game that bounces along like “Sing, Sing, Sing.”

And speaking of bouncing along: The minor league data shows a predictable effect on basestealing and basestealing efficiency. Implementing a pitch clock and disengagement restrictions (or The Runaway Bride Rule; everyone gets one cheap joke and this is mine) has increased the number of minor league stolen base attempts by 27%, according to MLB, and increased the success rate from 68% to 77%. Far be it from me to police anyone’s aesthetic preferences, but if you don’t want more stolen bases — particularly in this historical nadir of the art — you’re just wrong.

Now here’s the really exciting part. Last year, Craig Goldstein and Patrick Dubuque of Baseball Prospectus proposed a so-called restrictor plate for the modern pitcher; a series of minor reforms that would require teams to build rosters that valued bulk innings. To make a random set of 13 guys who spent a long weekend at Driveline and now throw 98 with Brad Lidge’s slider, for one inning at a time, a less tenable pitching staff.

Part of the calculus was a pitch clock; the grip-it-and-rip-it reliever needs 25 seconds to rest between pitches or else he’ll get tired before even one inning is over. Forcing pitchers to work more quickly would, the logic goes, force them to conserve their effort. That means less velocity, less oomph on breaking pitches, and a more hittable baseball. The potential downstream effects of this — fewer strikeouts, more balls in play, a greater premium on top-end starting pitchers — are so exciting I don’t want to get my hopes up.

This is what functioning sports leagues do: When the competitive incentives of the rules make the game less entertaining, they change the rules to correct the problem. That’s how the NBA got a shot clock, why FIFA implemented the backpass rule, and the NHL took out the redline. Similar changes for baseball were long overdue; if these rules are half as impactful as they look on paper, 2023 will be a watershed season.

Michael is a writer at FanGraphs. Previously, he was a staff writer at The Ringer and D1Baseball, and his work has appeared at Grantland, Baseball Prospectus, The Atlantic, ESPN.com, and various ill-remembered Phillies blogs. Follow him on Twitter, if you must, @MichaelBaumann.

I fully support gentle electrocutions for pitches over 94 mph. We could also use pitch data to shock pitchers whose sliders are too good, or whose change-ups are too slow relative their fastballs.

gentle or genital?

…why not both?

Genital electrocutions would encourage faster pitches in some guys.