The Astros Remind the Rays and Us of Their (and Our) Mortality

I haven’t conducted a study or anything, but I suspect that baseball fans assume themselves to be capable of playing at the highest professional level more than fans of any other professional sport. It’s not surprising; basketball players are 20 feet tall, all elbows and shoe-squeaks and legs, and football players have such obvious size. The line between civilian and non is clear. But baseball players exist on a continuum that has room for José Altuve and Ji-Man Choi, players who are by turns relatively small and squishy, and it creates the illusion that major leaguers are, or could be, just like us.

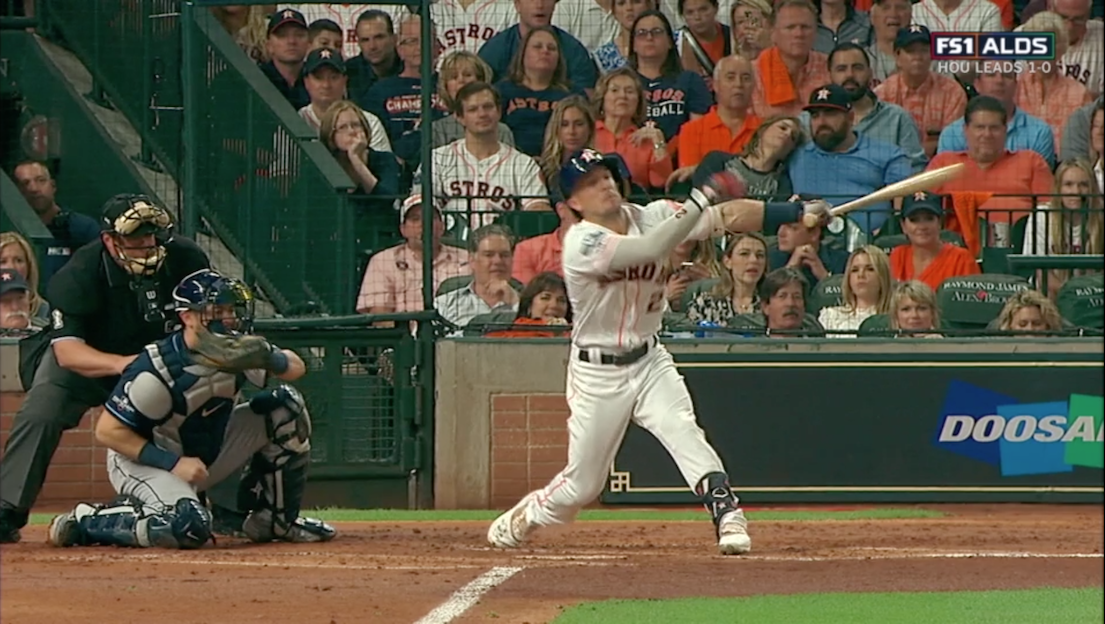

Only they aren’t. They are human beings possessed of feeling and ambition and meanness, of course, and someone, somewhere cares for them, but their smallness and squish aren’t like ours. Nowhere is that more apparent than in the postseason, when the small and the tall and the relatively-soft of middle remind us who they are, and thus, who we are. It’s easy to fool yourself into thinking you could trade places with some sad-sack on the 114-loss Tigers; it’s much harder to pull off the same con when faced with the Astros, however diminutive. Last night, Houston beat Tampa Bay 3-1 to take a 2-0 series lead, and in their dominance, forced us to recall just how great a distance there is between our beer-league softball teams, and the majors’ green fields, a lesson delivered in three parts.

On Futility

Every job has bits that are unpleasant. First, you have to get out of bed, which, wouldn’t you rather not? And then you have to drink coffee; you aren’t even sure if you like it, but you have to drink it, because, as we’ve established, you’ve been forced from your bed and now have to drive somewhere. Also, the coffee will give you heartburn. This will start when you turn 30, and I assume continue until you die, but before you do, there are expense reports and bad break room birthday cakes and staring at a screen or else lifting very heavy things, and to do all of that you have to be awake and away from your bed. I quite like my job, and I have stuff I wish I didn’t have to do in order to buy coffee, which again, I’m not sure I like!

But few things seem as professionally unpleasant as having to face Gerrit Cole, specifically this Gerrit Cole, of the 326 regular season strikeouts and 2.50 ERA and 2.64 FIP. Gerrit Cole, who struck out 10 or more batters in a game 21 times this season, and is likely to win the American League Cy Young, and has that fastball but also that slider and curve. It all amounts to some very bad break room birthday cake.

Cole faced 27 batters last night and struck out 15 in his 7.2 innings of work, good for a 17.61 K/9 and 55.6% strikeout rate. You could suss out those last two numbers on your own from the other three I’ve given you, but I think they merit explicit mention. They are awfully shiny. And he got his strikeouts using a democratic array of pitches, with five a piece coming on his fastball, slider, and knuckle-curve. (Each Ray struck out at least once, which is, I suppose, weirdly good for morale; the presence of workplace standouts tends to breed contempt.)

Cole threw 118 pitches; 83 of those were strikes, and 33 of those strikes were swinging, which, per Baseball Savant, represented a new single-game career high. He struck out the side in the second; he needed just 10 pitches to do it. The Rays only managed four hits all evening. In the top of the eighth, Kevin Kiermaier doubled to right. He was the only Rays hitter to advance past first base against Cole. After Kiermaier’s double, Cole issued his only walk of the contest, to Willy Adamas; the pitch that ran the count full, Coles’ 116th of the evening, came in at 100 mph.

Coles’ 15 strikeouts puts him into a five-way tie with Roger Clemens, Mike Mussina, Sandy Koufax, and Livan Hernandez for third-most in a postseason game, behind Bob Gibson (17 in Game 1 of the 1968 World Series against the Tigers) and Kevin Brown (16 in Game 1 of the 1998 NLDS against the Astros). He set a franchise single-game postseason strikeout record. When that’s the sort of day your competition is having, and all you can bring to the table is a slide deck and a team wRC+ of 102, it’s bound to be a bad time. (There is, as an aside, something deeply American about your reward for doing a lot of very good, hard work for months being more hard work that goes badly.)

Of course, Cole can oddly sympathize with the Rays’ plight. Will Harris would ensure that it all worked out, but despite Cole’s very fine day at the office, he had to watch, helpless and spent, as Roberto Osuna almost wasted it. After back-to-back singles to Austin Meadows and Tommy Pham, the broadcast camera panned to the dugout in time to show Cole abandon his spot on the rail and seemingly head to the clubhouse. I wouldn’t have wanted to watch either. Sometimes you land a big account, just really crush it, only to realize that some jabroni has had the last cup of coffee.

Which again, you’re not entirely sure you like.

Of Stretches and Flops

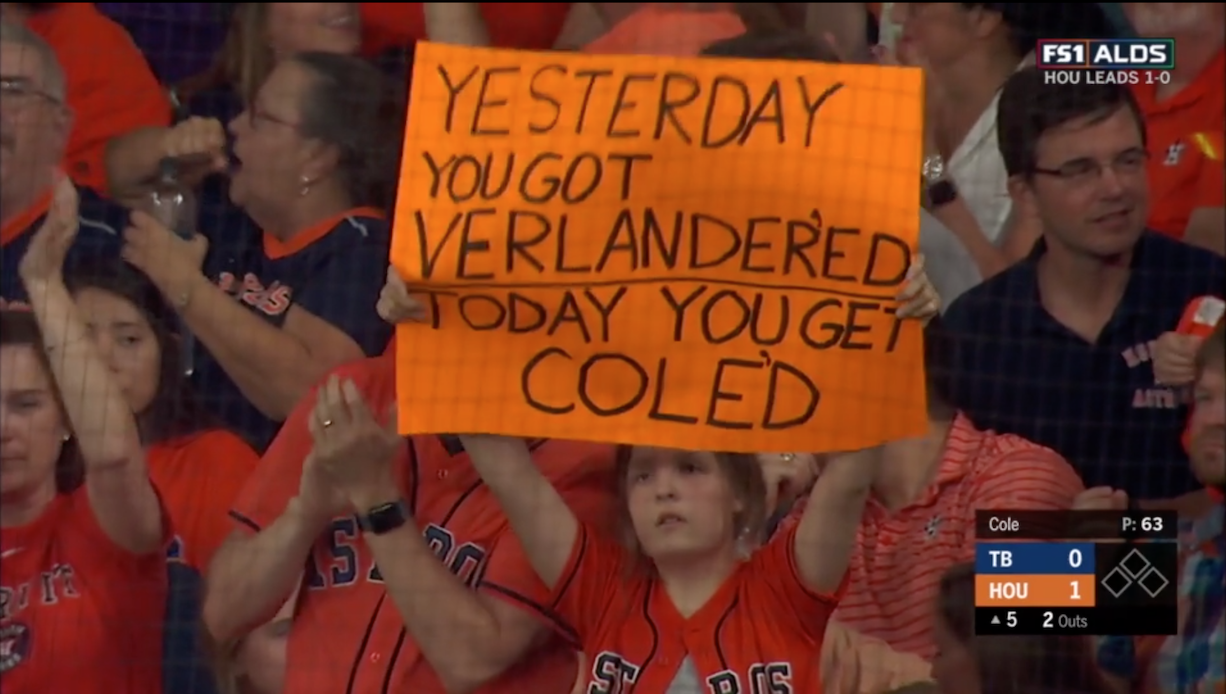

There are other ways we see the distance between ourselves and big leaguers manifest, apart from the baseballing. First, the players inspire people to make art:

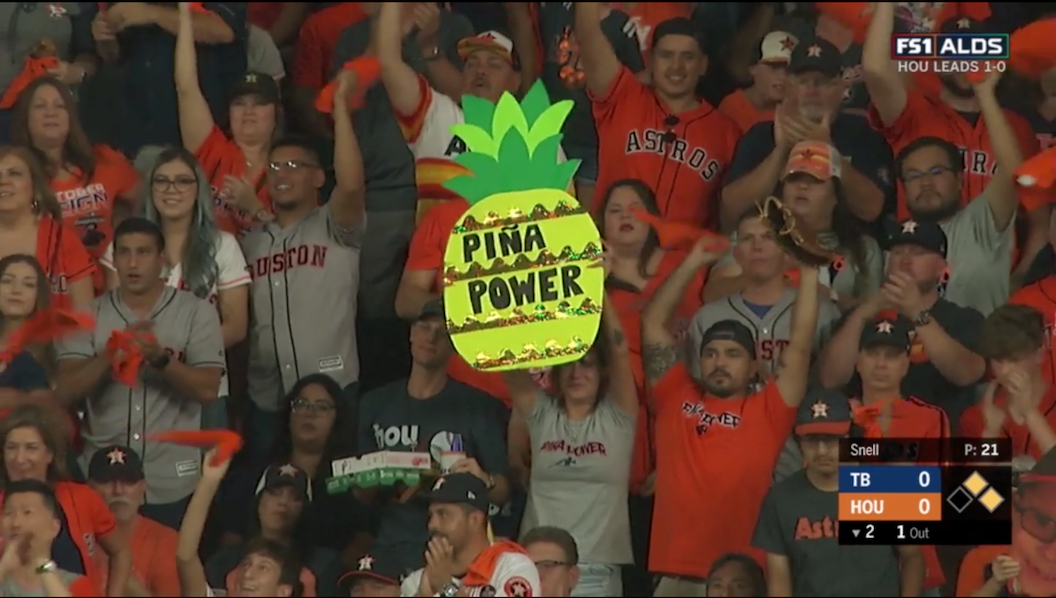

And exude permanent marker confidence:

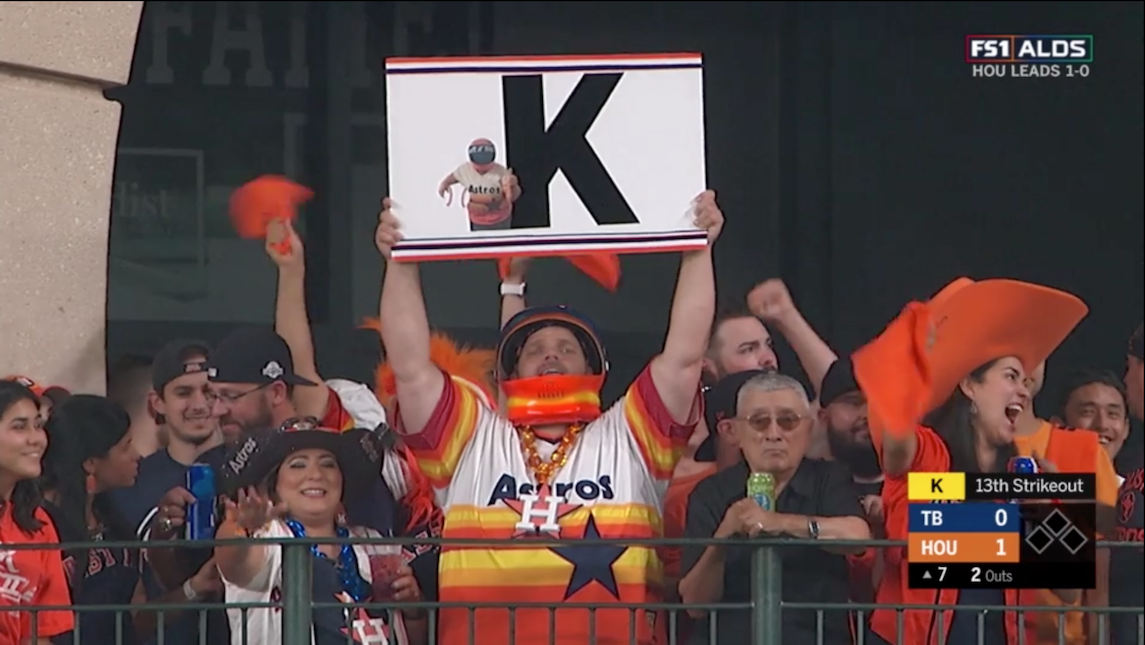

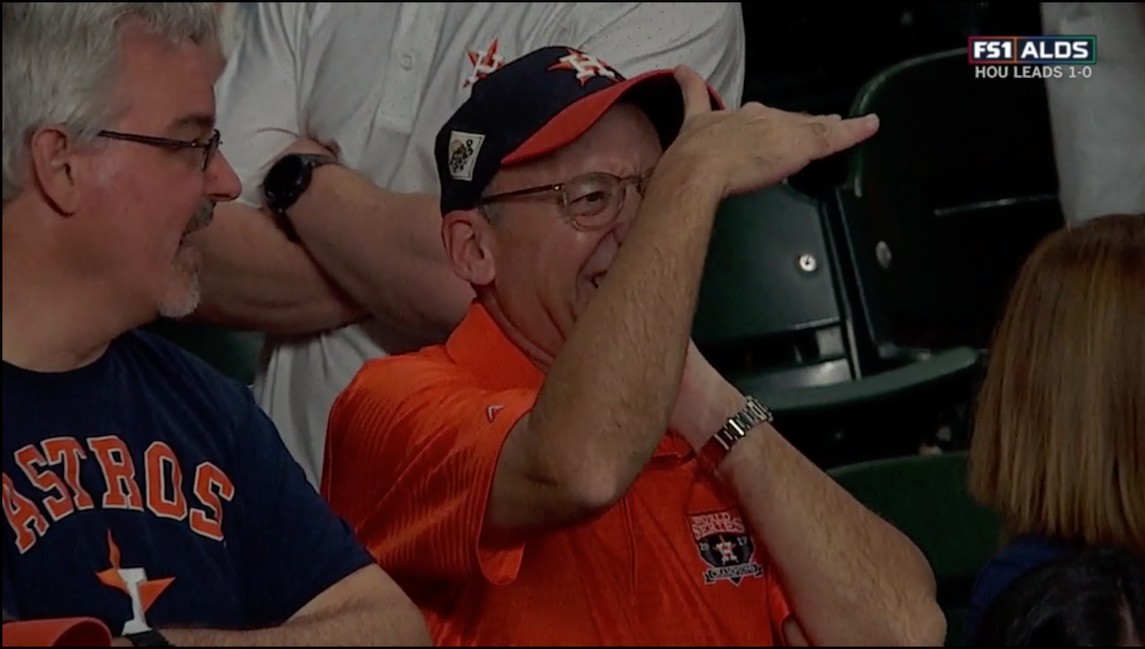

And get excited:

And be as Muppets:

And go all the way to space, or at least pretend they could:

They manage to spit perfect, tiny bits of spit that only very rarely get caught on their chins:

And they do stuff like this:

And this:

And then, they get back up. They walk around. They keep playing baseball. Sometimes they look cool doing it. Just look how cool Correa is. Flippin’ cool! But even when they don’t look cool, they don’t perish. They’re neither so embarrassed at looking a little silly flopping around (twice) nor so winded that they can’t continue. If I did what Choi did, excellent and flailing as it was, I’d use it as an excuse to have people bring me snacks for at least three days and possibly for the rest of my life, and people would understand. Because I’m a Meg. I flopped around and need help. I got the wind knocked out of me and have a scrape on my elbow. But these guys? They’re baseball players. People are ready to go to the moon for them! They fetch their own snacks, and then smile for good measure.

A Brief Note On Mortality

Of course, while major leaguers are quite unlike the fans in the stands, they bear a resemblance to each other. And given that one side wins and the other loses, there’s some obvious besting that goes on. Gerrit Cole bested the Rays. Austin Meadows, and Tommy Pham, and Ji-Man Choi, and Avisail Garcia, and Brandon Lowe almost bested Roberto Osuna, only Will Harris made sure they didn’t quite. Emilio Pagán got got by Martín Maldonado in the seventh, but the batter before, Kyle Tucker swung at a 97 mph fastball more than a foot above the top of the strike zone.

How high? This high!

Tucker would ground out two pitches later. I wonder if a small part of him that he wouldn’t admit to was keen to get back to the dugout and out of sight. He was bested, but it didn’t end up mattering. His team won; the ledger balanced out in their favor.

It should be noted that when mortals enter the fray, they often end up on the wrong side of it and against much worse competition. In the fifth, Martín Maldonado sent a Diego Castillo sinker down the left field line, where it collided with the Ball Boy’s (we will capitalize “Ball” and “Boy” here so as to give this young man the dignity of a name) stool (“stool,” though, will remain lowercase — it is a stool; it has neither a name, nor dignity), and took a favorable hop toward Austin Meadows, forcing Kyle Tucker (not yet bested) to stay put at third.

The broadcast was quick to note that the Incident was not the Ball Boy’s fault, and they were right. He’s told to sit there, and the ball came off Maldonado’s bat at 96.3 mph. He tried to move. Despite the nervy moments in the ninth, the unscored run wouldn’t end up mattering. But the broadcast returned to the Ball Boy at the top of the sixth, as if to remind those watching at home of whose territory the field of play really is: namely, those who aren’t undone by a stool, lowercase.

The mashing together of talented opponents means that even very good efforts are sometimes insufficient. The Rays held the Astros to just three runs. Per the Baseball-Reference’s Play Index, Houston was held to three runs or fewer just 54 times this season (only the Braves, Red Sox, Twins, and the Yankees met such a fate less often); the Astros won just 18 of those games. Houston struck out eight times. The Rays were in it! They had the right idea! Blake Snell, who since returning from the Injured List hadn’t gone more than two and a third innings in any of his three outings, pitched into the fourth and punched out five.

In the second, he struck out Alex Bregman swinging, and Bregman made this face.

The Rays, as far as the pitching was concerned, mostly had a good night. But they were bested. His next time up, Bregman would offer a very different face:

While Snell had two of his own:

Now, one run wasn’t enough. Martín Maldonado’s seventh inning RBI single against Emilio Pagán was necessary; Carlos Correa’s RBI in the eighth made for good insurance. Still, when Bregman hit his home run, it felt like enough. It felt like more than enough. The rational observer in us knows that even very good teams with starters in the midst of dominant outings can end up on the losing side of things. The Astros almost did last night. But that’s the power of gods and monsters and ballplayers. They best their fellows. They feel to us invincible. They make clear, with a thump and a fastball and a very good curve, that they aren’t like us, no matter how familiar the smallness and squish.

Meg is the editor-in-chief of FanGraphs and the co-host of Effectively Wild. Prior to joining FanGraphs, her work appeared at Baseball Prospectus, Lookout Landing, and Just A Bit Outside. You can follow her on Bluesky @megrowler.fangraphs.com.

Question, Meg: where are you getting that Cole only allowed 3 balls in play? He gave up 4 hits, yeah? Even with all his K’s and the one walk, there were still 11 of the 27 batters he faced who must have done something with the ball, even if a few of them might have popped out

Indeed — apologies, late-night brain. Updated, and thanks for reading.

Appreciate your work, thanks!