The Baserunning Madness of World Series Game 3

I honestly have no idea how many tag plays take place over the course of the average baseball game, but whatever that number may be, it felt like Game 3 of the World Series quadrupled it at the very least. We saw seven players thrown out on the bases. We saw challenges on plays at all four bases. We saw baserunning blunders, huge throws, and perfect relays. We saw aggressive sends that turned out well, and aggressive sends that led to players being thrown out at the plate by laughable margins. We saw pop-up slides that flew too close to the sun. We got a tutorial on the home plate blocking rule. We saw maybe the first ever umpire-induced pickoff. We saw the next day’s starting pitcher pull up with a leg cramp while running the bases in the bottom of the 11th inning. We saw multiple players get tagged out by a glove that caught them squarely in the Jonas Brothers. We saw the game’s 469th-fastest runner come in as a pinch-runner for the 606th-fastest runner. I could keep going.

At this point, I should mention that the litany you just read may or may not be my fault. Somewhere around the seventh inning, Meg Rowley asked me whether I might like to write about anything I’d seen during the game. I said there had been a couple interesting tag plays, so maybe it would be fun to write about them. Go back and reread the first sentence of this article. That’s when I wrote it, in the seventh inning, before like a dozen other absurd baserunning plays happened. This is how the baseball gods punish hubris, and there’s no way to delve into all these plays in one article. Even if there were, I wouldn’t be in any shape to write it, because I watched the entire 18-inning game and got like four hours of sleep last night (read: this morning). Instead, we’ll be taking a jogging tour of the tag play highlights, pointing out a few fun facts and then skating on to the next destination.

We’re going to ignore the most bizarre play of the game, because Michael Baumann has already written an entire article about it. The quick summary is that in the second inning, Daulton Varsho took ball four, so Bo Bichette started jogging from first base to second. Except home plate umpire Mark Wegner seemed to take offense when Varsho started heading toward first because the lefty slugger had the gall to assume that a pitch at his neck wouldn’t be called a strike. Wegner called the pitch a strike, very late. Bichette understandably missed the late call and the Dodgers hung him up between first and second. It was outrageous. Baumann’s got you covered. Let’s keep jogging.

We’ll start in the bottom of the third inning, when Freddie Freeman stole second base. Or did he? He was ruled safe on the field, and the call stood after the Blue Jays challenged. I went back to the technique I used to analyze a close tag play from the ALCS, pulling a slow motion clip into iMovie, zooming in on the tag and the foot touching the base in a slow motion in a split screen to see which happened first. As is often the case, Freeman’s cleat kicked a wave of dirt in front of it, obscuring the action. The only way to tell for sure when he touched it is to watch the base flex as it absorbs the pressure from his cleat. The first thing it does is pop off the ground by just a millimeter or so, because his cleat kind of digs under it. You can see a slight shadow beneath the base. Likewise, the camera angle is a little higher than the play, so the only way to tell when Andrés Giménez got his tag down onto Freeman’s shoulder is to watch for when the web of his glove starts to bend upward. If you watch it enough times, you’ll see that the glove flexes one frame before the base rises. By the slimmest of margins, Freeman should have been called out.

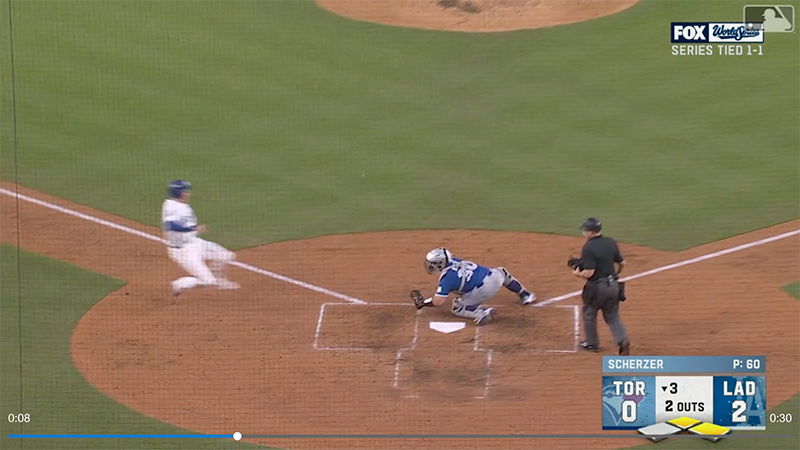

Fortunately, that didn’t matter much. The next batter up was Will Smith, who sent a single into right field, the domain of Addison Barger. As he did before uncorking a high-velocity assist in Game 2, Barger didn’t wind up for a huge throw. He didn’t charge the play with all he had. He made sure he got a comfortable hop and unleashed a perfect, unhurried throw. He was free and easy at 98.5 mph. Here’s the moment catcher Alejandro Kirk caught the ball. Notice anything missing?

Yeah, Freeman isn’t even in frame yet, which means he’s at least 20 feet away from home plate. The play ended up being somewhat close because Kirk chose to reach out and catch the ball a few feet in front of the plate, which meant he had to secure it, then swivel and reach backward. But even so, he was ready with the tag before Freeman was even into his slide.

In the sense that there were two outs, the Dodgers already had a 2-0 lead, and it took a perfect throw to catch Freeman, you could argue that it was a reasonable send by third base coach Dino Ebel. But knowing about Barger’s penchant for perfect throws, it’s easy to argue against the send, too. Regardless, it wasn’t the most reckless send of the night by a longshot.

The next baserunning decision was hugely consequential. In the top of the third, Giménez came up with one out, runners on the corners, and the Blue Jays down 3-2. He hit a perfect sac fly into deep center field, and Barger tagged up to tie the game. In fact, the ball was so deep that over at first base, Ernie Clement also decided to tag up. He came about four inches from making the third out at second base. Even though Barger was aware of the situation and ran hard from third, he was still a few feet slower than Clement. Had Clement been thrown out, the run wouldn’t have scored and the Dodgers would have held onto their lead.

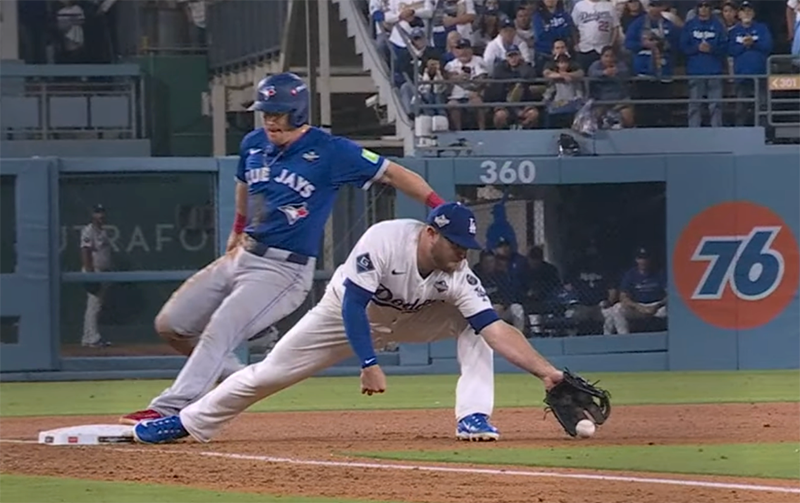

Teoscar Hernández was on first in the sixth inning with two out and the score tied, 4-4, when Enrique Hernández hit a groundball into the six-hole. Giménez backhanded it on the outfield grass, turned and heaved a jump-throw across the diamond that was too short, too wide, and too late to get Enrique Hernández at first. However, first baseman Vladimir Guerrero Jr. recognized two things on the play: 1) that the throw had no chance of getting the batter, and 2) that Teoscar Hernández had rounded second and was steaming toward third. Guerrero doesn’t have the best range, but he loves to show off his arm, and that inclination served him well here. He acted decisively, shooting off the bag to meet the ball, scooped it, and despite slipping, he reared back and fired a low-flying dart that gave third baseman Clement a perfect long hop. The throw led the glove directly into the path of the sliding runner. Clement applied the tag in time; the Dodgers challenged, but the call was confirmed.

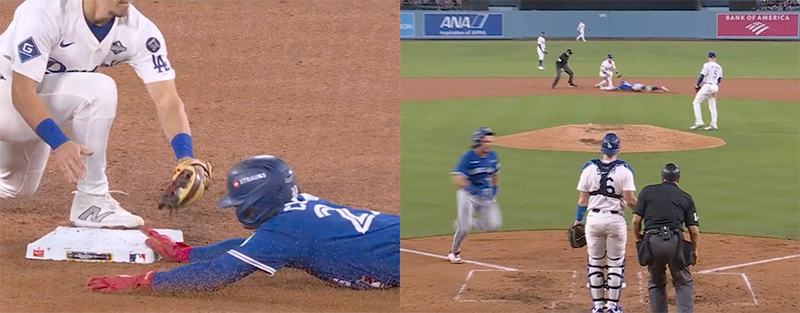

Without a doubt, the evening’s most fun baserunning play came in the top of the seventh, and it featured the two main players from the one that ended the sixth, only their roles — as well as the calls — were reversed. With Guerrero on first base, Bichette poked a single right down the first base line. The ball went out of its way to introduce itself to every human being in Dodger Stadium. It just sneaked wide of Freeman and inside first base umpire Alan Porter. Right field umpire Adrian Johnson dodged out of the way before ruling it fair. It then sliced into foul territory and headed for the side wall, where two ball boys and a sound guy holding a giant parabolic microphone formed an unlikely chorus line, pirouetting out of the way in unison. The only person the ball didn’t seem to want to meet was Teoscar Hernández, who was headed toward the corner and had to change directions when the ball caromed off the side wall and ended up in shallow right. Guerrero didn’t look to be running all that hard as he neared third. In fact, he was grinning as if to say, “Look how hilarious it is that I, Vladimir Guerrero Jr., have been forced to run all this way!” The kick off the side wall changed all that. Third base coach Carlos Febles waved him home, so Guerrero picked it up, after his own fashion. “How fast can Vlad run?” shouted Joe Davis on the Fox broadcast, but he knew the answer. We all knew the answer: Not fast at all. Here’s Smith with the ball. No Vladdy in sight.

Hernández’s throw beat him by a country mile, but it came in way off line, which set up Guerrero and catcher Smith for a tandem diving play at the plate. But Guerrero didn’t dive. He slid hard onto his left haunch, then bounced up and flipped over to his right side, landing in a crouch and tapping the plate with his hand with mere inches to spare.

The internet immediately christened it the boop tag, and who are we to argue with a name so pure?

Seriously, watch for yourself. He really did boop it.

We’re now more than 1,500 words into this article, and the game is not yet half over. Let’s keep jogging, shall we? With a runner on first in the top of the ninth, Varsho ripped an absolute bullet down the first base line. The ball looked sure to score Isiah Kiner-Falefa from first if not for two unbelievable defensive plays. The first came from Freeman, who leaped and got just a bit of leather on the ball, deflecting it into the air to die in shallow right field. The second came from second baseman Tommy Edman, who didn’t hesitate for a moment to throw himself after the ball. He slid past it in order to glove it and come up firing in one fluid motion. Peter Abraham of the Boston Globe compared it to one of Trea Turner’s famous slides into home plate. Edman unleashed a perfect throw to nail Kiner-Falefa at third. It was a thing of beauty.

The next weird play came when the Blue Jays intentionally put the winning run on first base with one out in the bottom of the ninth, because the winning run came in the form of Shohei Ohtani. Ohtani got a huge jump and stole second, but only for a millisecond. An absolutely perfect throw from Kirk forced Ohtani to charge into the bag, and he executed a pop-up slide that featured way too much pop. Ohtani bounced up and off the bag, and Kiner-Falefa’s insistent, inconveniently placed tag caught him in midair.

The Dodgers lost the chance to have the winning run in scoring position with one out because Ohtani couldn’t stay on the bag but Kiner-Falefa could.

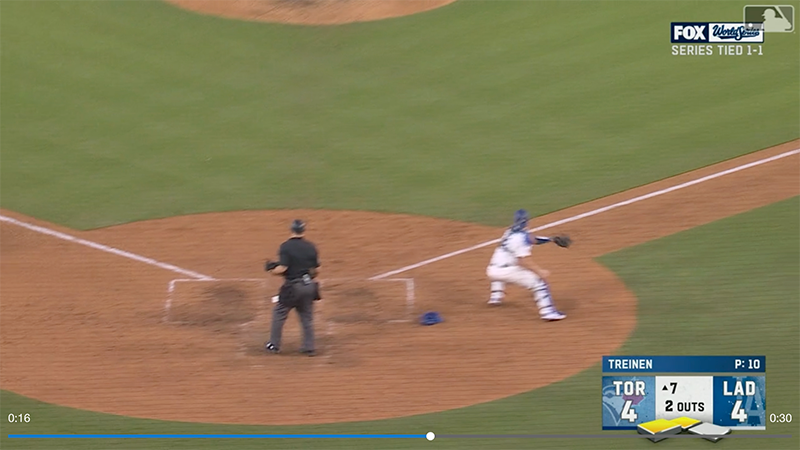

Once again, we only had to wait until the next half inning for the next thrilling baserunning play. With two outs in the top of the 10th, Nathan Lukes ripped a double into the right field corner, and for once, the ball actually got all the way to the corner! Davis Schneider was on first base, and he was looking to score from the get-go. This time, Hernández was right on target. He hit Edman perfectly, and Edman unleashed his second excellent throw of the night, a well-placed relay to Smith at home. Schneider never stood a chance. Smith, not knowing where exactly the runner was, whipped around and slapped a tag in front of home plate as soon as he got the ball. His glove slammed into the ground before Schneider was fully into his slide. Instead of having Guerrero up representing the winning run on third, the Blue Jays went scoreless. Want to see another picture of a catcher receiving a throw with no baserunner in sight?

The Blue Jays sought to challenge the play on the grounds that Smith had blocked the plate before he’d caught the ball, when the runner was still somewhere around Barstow. Fox even brought on a former umpire as a rules expert to explain the blocking rule. “And then, would the runner be able to run over the catcher at that point?” asked John Smoltz, sounding like he’d finally found a part of the game that he truly enjoyed talking about.

Things got genuinely weird in the 12th inning. Kirk reached first base with no outs, and manager John Schneider decided to pinch-run for him with the only player left on the bench: backup catcher Tyler Heineman. Heineman features 24th-percentile sprint speed, compared to Kirk’s second-percentile sprint speed. He’s faster than Kirk in the way that crawling is faster than bear-crawling. The upgrade was so marginal that it seemed impossible that it could be worth the risk of pulling Kirk, one of the game’s greatest catchers both offensively and defensively. And yet it paid off almost exactly as Schneider had foreseen.

With two out, Davis Schneider came to the plate with Kirk on second and Giménez — Toronto’s no. 9 hitter whom the Dodgers had just intentionally walked — on first, and he tapped a bouncer right at third base. Third baseman Max Muncy stepped on the bag and waited for the ball to arrive, stretching like a first baseman for the forceout. Heineman trundled toward third with everything he had. It was very little. The umpire called him out. He didn’t even slide because he was running so slowly that after his left foot landed on the bag, he was able to come to a dead stop with just one step from his right foot. But the umpire was wrong. Heineman had beaten the bouncing ball by the slimmest of margins. Kirk never would have made it. In a game that featured both a seventh- and a 14th-inning stretch, the 12th-inning stretch came up just short.

The Blue Jays had the bases loaded in the 12th inning, all because Schneider decided to empty his bench and pull one of his best players out of the game in search of the most marginal improvement imaginable. But they didn’t score. And so Kirk watched the next six innings from the bench as Heineman took three plate appearances.

As wild as all these plays were, I’m not even sure you could argue that they were the most remarkable thing about Game 3. About a dozen other wacky things occurred during the 18-inning marathon that ended on a walk-off homer from Freeman, the guy who hit a walk-off grand slam in last year’s World Series. Defensive replacements played more innings than the players they replaced. Ohtani reached base nine times with four intentional walks! Clayton Kershaw got one big out, and then the Dodgers, for once, decided to just leave it there and bring in another pitcher. Edman made yet another fantastic play. The Blue Jays brought fruit platters out to the dugout for their big, hungry players. Once the innings were old enough to drive, the Dodgers clobbered several balls to deep center, but by that time the marine layer had moved in, causing them to die on the warning track. One of those would-be homers came after the Blue Jays loaded the bases in order to face the player who would later go on to hit the walk-off home run, atmospheric conditions be damned. Will Klein, who ran a 6.14 ERA in the minors this season, went four scoreless innings and threw 72 pitches, exactly twice as many innings and pitches as his previous high in a major league game. It was all so weird, and we skipped the weirdest play of all because Baumann got there first. There’s another game tonight. I’m sure it’ll be totally normal.

Davy Andrews is a Brooklyn-based musician and a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @davyandrewsdavy.bsky.social.

It’s crazy to me how many people think it’s understandable that Bichette walked into a free out. I’ve seen so many late and controversial ball four strike calls in lots of baseball-watching experience. What I’ve never seen is a baserunner who was so sure a pitch was a ball that he couldn’t be bothered to double check that the ump called it a ball before turning his back to the play and wandering into no man’s land!

And the call really wasn’t THAT late!! The audible call was immediate and the hand signal was two seconds later!

Are we all just surrendering to the groupthink of Joe Davis and John Smoltz!? Even the Blue Jays radio broadcast admitted immediately that it was a mistake by the Blue Jays.

Especially when Smoltz is *awful* at his current job.