The Incomparable Adam Wainwright

I’ll forgive you if you thought Adam Wainwright was cooked in 2018. He landed on the IL after three middling starts (12 strikeouts in 15.2 innings, a 3.45 ERA and 5.20 FIP), made a single short start in May, then didn’t pitch again until September. His sinker had never been slower; his curveball had never had less bite. At 37, that’s a scary combination, and it hadn’t come out of nowhere; he posted an ERA of 5.11 in his previous season, along with career-worst marks in K%, BB%, and FIP.

Three years later, Wainwright is a down-ballot Cy Young candidate. He’s accrued as much WAR as the next five Cardinals starters combined. St. Louis probably won’t make the playoffs, but it won’t be because of the once and current ace, a timeless wonder having his best season since before tearing his Achilles in 2015. How has he done it? I’m glad you asked.

Major leaguers are so good these days, on both the pitching and hitting side. Batters have never hit the ball harder on contact or tried so hard to hit home runs. It’s scary out there for a pitcher; any contact could leave the park at the drop of a hat. Pitchers have compensated in the obvious way: throwing pitches that avoid contact. Swinging-strike rate and strikeout rate are both marching inexorably higher, with occasional step changes (the sticky stuff crackdown, for example) fighting the tide.

Wainwright doesn’t have that option, though. If you asked him candidly, I’m sure he’d love to throw 95 mph and snap off sliders that turn into Pitching Ninja GIFs. But that was never his game, and he wasn’t going to suddenly turn into that kind of pitcher at age 39. In fact, when Wainwright began to decline, that was the common diagnosis. An aging sinker-first pitcher in the age of four-seamers? Sounds like a recipe for failure.

That’s all true! Wainwright’s sinker virtually never induces an empty swing. That’s not even a new thing; he’s only had one year in his entire career with a swinging-strike rate above 5% on the pitch. He’s only had a whiff rate higher than 10% in two of his 14 seasons. When batters take a cut, they mostly hit the ball.

In a vacuum, that’s a pretty bad pitch. Luckily, pitching doesn’t happen in a vacuum. For one thing, everyone would suffocate. Even in a metaphorical vacuum, context matters. For example, take a look at league-wide swing rates on sinkers by count:

| Count | O-Swing% | Z-Swing% | Heart Swing% |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-0 | 14.4% | 41.9% | 47.9% |

| 0-1 | 28.7% | 71.3% | 78.5% |

| 0-2 | 29.9% | 78.5% | 87.5% |

| 1-0 | 22.4% | 58.8% | 67.1% |

| 1-1 | 28.1% | 73.0% | 81.8% |

| 1-2 | 31.5% | 81.7% | 90.2% |

| 2-0 | 19.7% | 59.2% | 66.2% |

| 2-1 | 30.3% | 76.8% | 84.9% |

| 2-2 | 36.1% | 83.7% | 90.2% |

| 3-0 | 4.0% | 15.0% | 16.8% |

| 3-1 | 26.6% | 72.6% | 80.3% |

| 3-2 | 41.4% | 89.2% | 94.8% |

That’s a big pile of data, but you can think of it this way: in zero-strike counts, batters are passive. In every other count, they’re extremely aggressive in the strike zone, even more so over the heart of the plate. Even in a 3–1 count, batters swing nearly three-quarters of the time at sinkers thrown for strikes. There’s no sitting and waiting here; batters know that two-strike counts are bad for their health and that fastballs are good to hit. Throw them a bone, and they won’t pass at the chance.

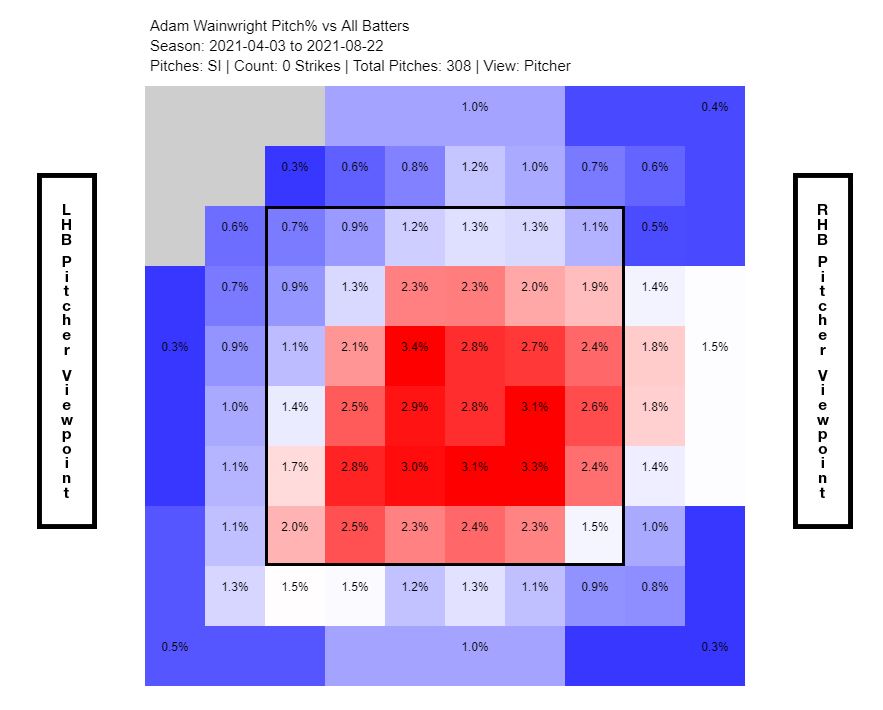

With no strikes, Wainwright doesn’t mess around:

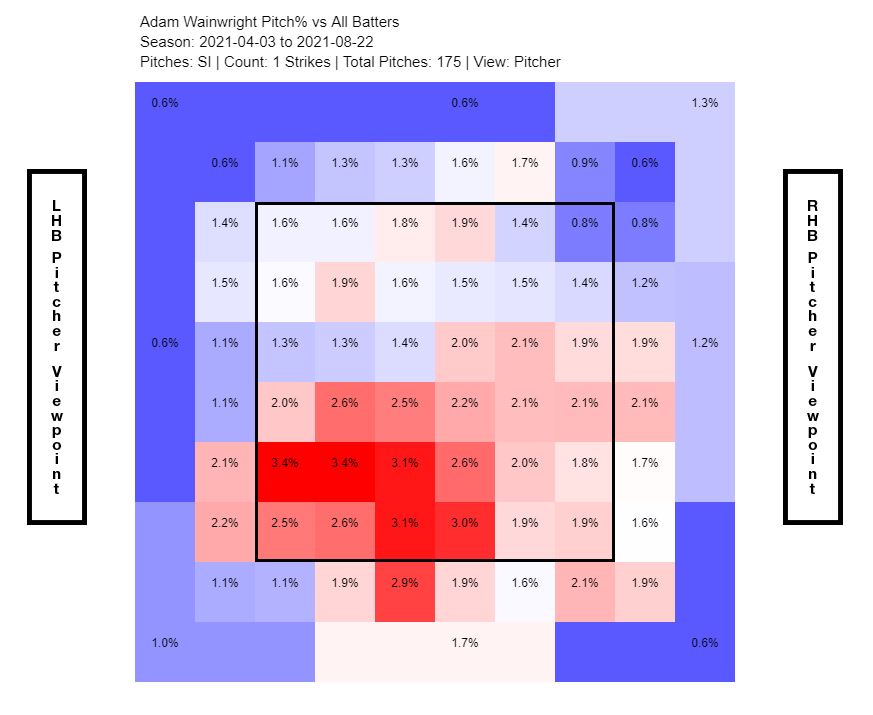

With one strike, he turns into a surgeon. Seriously, it’s hard to overstate how impressive this location chart is:

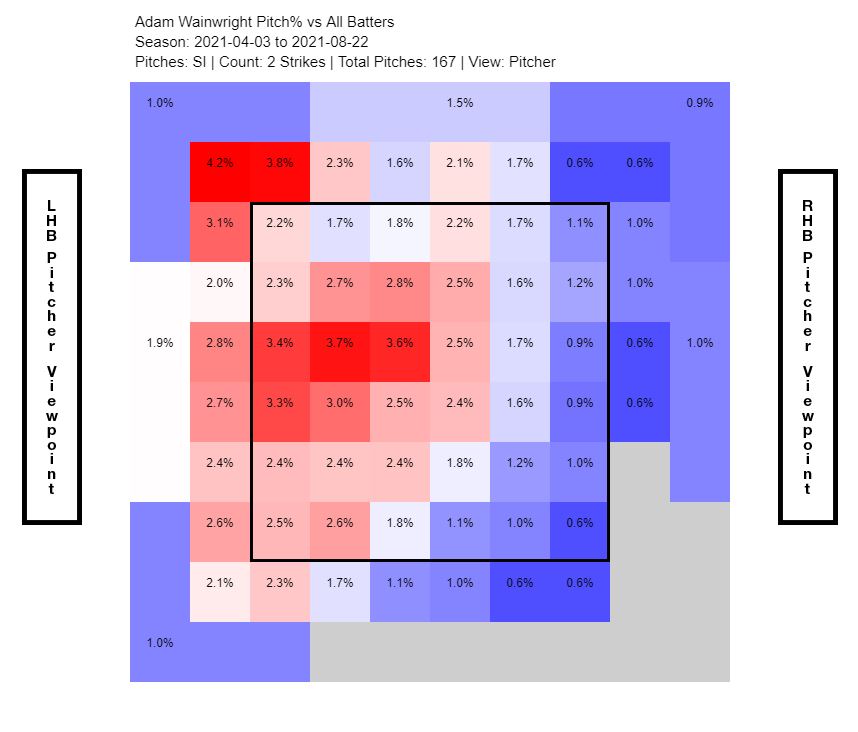

He simply doesn’t give in. If you want to swing at a sinker — and again, batters do — you’re going to be swinging at a miserable one, on the knees and at the corner of the zone. He’s not quite as clean with two strikes, but honestly, it would be hard to be that good:

Still, the net degree of difficulty is outrageous, and that location is still excellent. Wainwright is in the top 25% of the league when it comes to avoiding the heart of the strike zone with his sinker (in one- and two-strike counts). He’s also in the top 25% of the league when it comes to hitting the shadows of the zone — the area just inside or just outside of the strike zone boundary. In other words, he’s great at getting the ball over the plate, but not all the way over the plate.

That’s key, because even if you give up contact, where you give up contact matters. When batters put sinkers over the heart of the zone in play, they produce a wOBA of roughly .400. That’s roughly what Juan Soto and Joey Votto are producing on the year as a whole. That’s not a place you want to live. Give up contact in the shadow zone, and things aren’t so bad. Those batted balls have produced a .320 wOBA, which is roughly league average production. Contact is supposed to be the dangerous thing; overall average production includes strikeouts and walks. If that’s the downside when batters make contact, you’re doing well.

That’s not enough to explain all of Wainwright’s sinker-based mastery this year; even when you locate it perfectly, batters can still go out and get it. As we already covered, they’re really good these days. But batters have underperformed their expected production when they put a Wainwright sinker into play. Why? Well, it helps to have Harrison Bader patrolling the outfield:

It also helps to have Nolan Arenado patrolling the infield:

In fact, Wainwright is first in all of baseball when it comes to outs saved by the defense behind him. He gives them plenty of chances by limiting walks, strikeouts, and home runs, and the Cardinals have rewarded him with a whopping 18 outs above average.

That’s no slight on Wainwright, though. This Cardinals team is built to convert balls in play into outs. Their everyday lineup sports seven plus defenders at the eight available spots, with Dylan Carlson the lone minus. But even Carlson has excelled with Wainwright on the mound; right field has been worth two outs above average this year behind the Cards’ old ace — more than Arenado’s third base spot has added, per Statcast.

So far, I’ve focused on Wainwright’s remarkable ability to throw in and around the zone without giving up layups (or open corner threes, depending on which basketball analogy you prefer). That helps him limit walks; his 6% walk rate is stellar, particularly for a pitcher without the stuff to throw it down main street and challenge hitters to catch up.

That’s only half the picture. That sinker, valuable as it’s been at stealing strikes early and dotting corners late, isn’t striking anyone out. Well, it isn’t striking anyone out swinging at least. He’s generated 32 called strike threes with the pitch this year, the third-best mark for any sinker. Watch this nonsense and marvel:

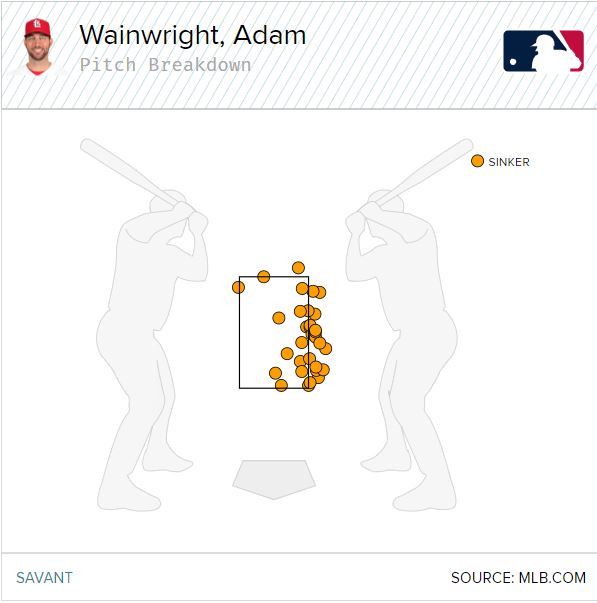

That’s legitimately perfect. When you’re throwing fastballs in the 80s against borderline MVP candidates, there’s no margin for error. An inch further inside, and it would have been ball two; an inch over the plate, and Reynolds likely would have swung. That pitch — a front-door strike that starts over the hips to lefties and a back-door robbery to righties — has served Wainwright well all year, as has some judicious receiving by Cardinals catchers (largely Yadier Molina):

That’s the location of all of his called strikeouts on sinkers, and if you’re a batter, there aren’t many good options. It’s hard to put a good swing on a ball there, but taking it obviously didn’t work out either.

Still, you can’t strike everyone out with the bat on their shoulders, which means curveballs. That’s been his best pitch throughout his major league career, and this year is no different. It’s a giant, two-planed curve, one of the fastest-spinning pitches in the majors despite mid-70s velocity. The combination of slow speed and hellacious break means that the pitch drops a preposterous 66 inches from its initial trajectory on its way home. This one to Ke’Bryan Hayes started out at eye level:

On the other hand, this one to Bryce Harper went from mashable fastball to “hey where’d it go?” in a hurry:

Not everyone can throw a curve with so much bite. Even fewer know how to use it, and Wainwright is a master of the craft. Those big silly hooks that go from hittable to bouncing are fun, but look where the run value has come from this year:

| Zone | Run Value |

|---|---|

| Heart | -10.7 |

| Shadow | -3.6 |

| Chase | 1.2 |

| Waste | 3.2 |

The shadow and chase numbers are misleading, because you can live with some balls (positive run value for the batter, of course) if you get the occasional strikeout. But the majority of the value comes from throwing a slow pitch right down the middle. It’s wild!

Roughly half of that comes on called strikes. Only Julio Urías has thrown more curveballs for a called strike to open at-bats. Wainwright has 87 on the year, 44 of which have been middle-middle. It’s so hard to pull the trigger on those, even if you know they’re coming; batters have swung only 33% of the time. Even when they swing, Wainwright seems to win; he’s allowed only two hits on these grooved 0–0 curveballs all year, though one was a homer. He’ll throw a curve for a strike in any count, but he’s most prolific to start at-bats.

If batters do swing at these heart-zone curves, they mostly make contact. It’s hard to miss bats with a curveball that you send right down the pipe. Batters have come up empty on only 14% of their swings at center-cut curveballs this year. That’s a roughly average rate. But making contact isn’t the same as making solid contact. In fact, when batters manage to put these center-cut breaking balls into play, they don’t do all that well, hitting .250 with a .486 slugging percentage on fair contact, good for a .305 wOBA (.339 xwOBA). That compares to a league-wide number that hardly looks like the same pitch type: a .344 batting average and .622 slugging percentage, good for a .401 wOBA (.393 xwOBA).

How can Wainwright get away with it? He’s probably getting a little lucky. More relevantly, batters pretty much never face anything comparable to the slow hook. The list of players whose curveballs get more total movement isn’t a list: it’s just Rich Hill (Paolo Espino is in the neighborhood, to be fair). It will hardly surprise you to learn that Hill, too, fares well even when batters hit curves he throws over the heart of the plate. The massive two-plane break is simply hard to square up.

Wainwright throws three other pitches: a four-seam fastball with solid ride, a mid-80s cutter he uses to mix up his fastball looks, and a changeup he sprinkles in against lefties. Those help keep hitters off the curve and sinker, but the two pitches that he’s always thrown best have done the heavy lifting this year.

That miserable 2018 season that opened this story might have provided the catalyst that brought Wainwright to his current form. He might not have pitched very often, and he might not have pitched very well when he was available, but he came out slinging curves early and often. He threw 30% or more curves in seven of his eight starts after never throwing 30% curves in a year before 2018. Heck, he almost never threw 30% curves in a single start before 2018, much less a full year. Only 20% of his previous starts had been so curve-heavy. Since the start of 2018, 85% of his starts have been at least 30% curves, and more than a quarter have featured 40% breaking balls. It’s an admirable move: when his fastball wasn’t cutting it, he simply started jamming his best pitch more often.

Can his superlative form continue? Time is still undefeated, so it can’t go on forever. He’s gotten help from his defense — partially by design, but still. He’s hitting his spots perfectly; just a little worse, or even just a little slower, and the magic might stop working. There’s no reason to think it’s happening this year, but eventually, nothing keeps going.

Instead of thinking about the future, though, think about the difficulty of the present. Every single time that Wainwright faces a batter, he has to beat someone with better physical tools. If he misses his spot, he’s throwing a low-velocity fastball into the nitro zone. If he overcooks a curveball and hangs one, same deal.

And he keeps doing it! Batter after batter, he walks a tightrope successfully. He keeps the ball in play. He lets the defense help him. But plenty of the time, it’s just him out there, his curveball against the batter. Every single pitch is a chance to fail, and Wainwright just keeps… not failing. It’s a singular accomplishment, and as the game changes more and more around him, it’s an absolute joy to see him keep succeeding.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Bravo Mr. Wainwright