The Math Behind the Extra Innings Home Field Disadvantage

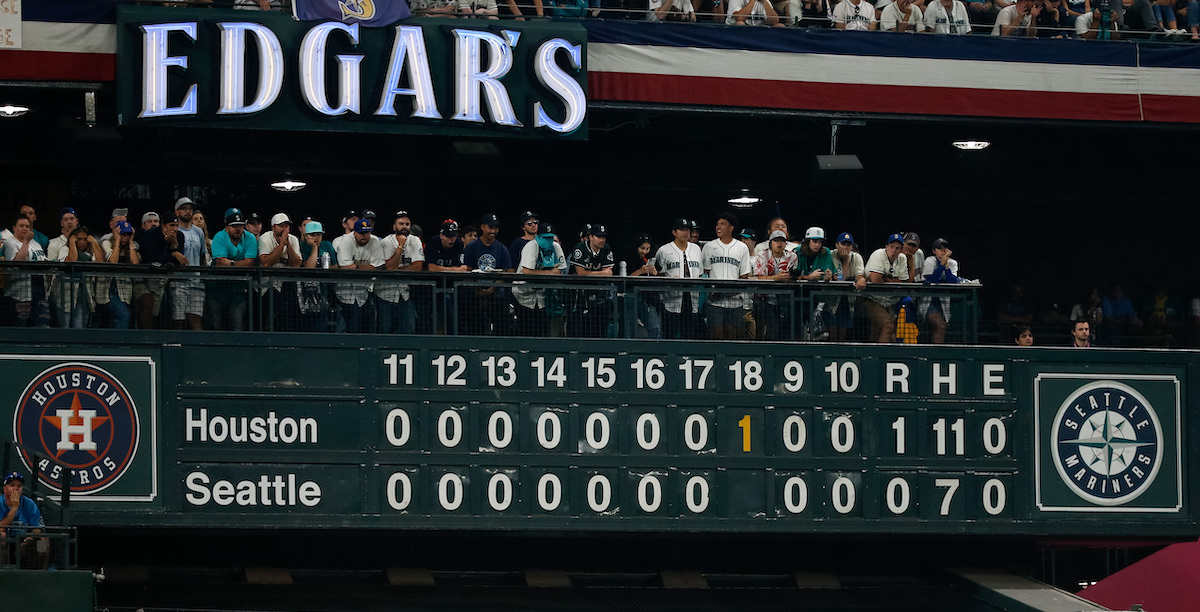

Home teams don’t win enough in extra innings. It’s one of the most persistent mysteries of the last five years of baseball. Before the 2020 season, MLB changed the extra innings rules to start each half of each extra frame with a runner on second base. (This only occurs during the regular season, which means the 18-inning ALDS tilt between the Mariners and the Astros in the picture above didn’t actually feature zombie runners, but the shot was too good to pass up.) They did so to lessen the wear and tear on pitchers, and keep games to a manageable length. Almost certainly, though, they weren’t planning on diminishing home field advantage while they were at it.

In recent years, Rob Mains of Baseball Prospectus has extensively documented the plight of the home team. Connelly Doan measured the incidence of bunts in extra innings and compared the observed rate to a theoretical optimum. Earlier this month, Jay Jaffe dove into the details and noted that strikeouts and walks are a key point of difference between regulation frames and bonus baseball. These all explain the differing dynamics present in extras. But there’s one question I haven’t seen answered: How exactly does this work in practice? Are home teams scoring too little? Are away teams scoring too much? Do home teams play the situations improperly? I set out to answer these questions empirically, using all the data we have on extra innings, to get a sense of where theory and practice diverge.

The theory of extra inning scoring is relatively simple. I laid it out in 2020, and the math still works. You can take a run expectancy chart, start with a runner on second and no one out, and figure out how many runs teams score in that situation in general. If you want to get fancy, you can even find a distribution: how often they score one run, two runs, no runs, and so on. For example, I can tell you that from 2020 to 2025, excluding the ninth inning and extra innings, teams that put a runner on second base with no one out went on to score 0.99 runs per inning.

That’s the relevant situation that road teams face in extras. They have a runner on second with no one out to start the inning, and they’re trying to score runs. They’ve been fairly successful at it, scoring 1.00 runs per inning across the 1,354 extra innings in my sample. That’s statistically indistinguishable from the overall major league average. Break it down by frequency of result, and you still can’t see much difference:

| Scoring | Regulation | Top of Extras |

|---|---|---|

| 0 Runs | 45.6% | 47.5% |

| 1 Run | 31.1% | 28.3% |

| 2 Runs | 11.7% | 11.1% |

| 3+ Runs | 11.6% | 13.1% |

The difference in run-scoring frequency is right on the border of statistical significance, but the direction makes sense. Visiting teams put up exactly one run slightly less frequently than a naive run expectation, which tracks with how extra inning games work. As Jaffe’s research demonstrates, strikeouts increase in extra innings. The defensive positioning and strategy in extra innings prioritizes maintaining a tie; teams play the infield in and try to make plays at the plate at a higher rate in the 10th inning than in the second, naturally enough. For the most part, though, visiting teams in extras are scoring exactly how we’d expect based on the broad performance of the league as a whole over the past half decade.

With that data in hand, we can focus on the home team. Unlike most analyses, we already know what we’re going to find here in broad strokes. Visiting teams convert the runner on second base into runs at the same rate they do in regulation innings. Home teams must not be, what with them winning fewer extra inning games than you’d expect and all. But how and where do they come up short? The data has to be our guide.

Consider the situation where the visiting team fails to score in the top half of the inning. A naive expectation, completely ignoring the particular strategies each team might deploy in extras, suggests that the home team would score around 55% of the time – one minus the chance of scoring no runs after starting with a runner on second and no one out. What has actually happened? The home team has scored about 56.5% of the time. How many runs they score – and thus, the run expectancy – is pointless. If they score in this scenario, that’s enough to win. Here, at least, home teams are performing exactly as you’d expect from the way they score runs during regulation innings.

Let’s move on. What happens when the home team starts the bottom half of an extra inning down by a run? Using our naive probabilities from up above, you’d expect them to score zero runs and thus lose 45% of the time. Instead, they’re coming up empty 49.1% of the time. You’d expect them to score one run and tie the game, sending it to another frame, a further 31% of the time. In reality, though, teams only scratch out that tying run 29% of the time. Finally, you’d expect home teams to score twice and win about 23% of the time, but they’re doing so only 22% of the time. In other words, after the visiting team gets ahead in the top of the inning, they close the game out more frequently than you’d expect based on the league’s overall production with a runner on second base and no one out.

That gap explains a substantial portion of the home field disadvantage associated with the new extra innings rule. Home teams have started the bottom half of an extra frame with a one-run deficit 389 times under the new rules. If they scored the same way they do in regulation, they’d end up with 177 losses, 91 wins, and 121 times where they re-tie the game and send it to a further extra frame. Instead, they’ve racked up 191 losses, 86 wins, and 112 times scoring a run and keeping the game going. That net shortfall of 19 games – 14 more losses and five fewer wins – is about two percentage points of winning percentage across the entire population of extra inning games. Per Mains, home teams won at a 49.3% clip in extras from 2020 through 2024, as compared to a 52.2% rate under the classic extra innings rules.

If we’re looking for specifics, it would behoove us to zoom in on why teams can’t cash in that zombie runner often enough to tie the game. That’s the sticking point in this analysis. In regulation innings, that runner scores far more frequently than in extras. It’s not hard to understand why. The defense is different, after all. With a runner on third and one out, the defensive team has a wide array of options. They could bring the infield in and pitch for a strikeout. They could concede the run. They could intentionally walk someone to set up a double play.

In the early innings, teams almost always concede the run in exchange for a strategy that is most likely to record some type of out, run-scoring or otherwise, which seems wise. Playing to the score doesn’t make much sense when most of the game is still left to play. In the later innings, however, most defenses will switch tactics, prioritizing lead preservation over the highest chance of generating an out.

As an example, consider home teams playing defense in the top of an extra-inning frame. When a runner reaches third with no one out, the visiting team scores 82% of the time. When a runner is on third with one out, they score 65% of the time. These numbers are roughly in line with what happens in the same situation in regulation; the visiting team scores a hair less often in extras than in regulation, but within the margin of error. Maybe the defense is expending effort trying to prevent that one run, but the offense is expending an equal amount of effort trying to score it (running on contact, shortening swings in pursuit of balls in play, etc.), and the net result is that visiting teams cash in runs at essentially the same rate whether they’re playing in regulation or extras.

Take a look at the home side of things, on the other hand, and you’ll see a difference. When the home team puts a runner on third with no one out in a tie game in extras (small sample alert), they only cash in that runner 75% of the time. A runner on third with one out? They score 58% of the time. Down a run, those numbers are roughly the same. The sample is small on all of these, of course, but there’s no denying what has happened so far. That’s meaningfully lower than you’d expect from the scoring environment that prevails in regulation. In other words, home teams aren’t as good at cashing in runners from third in extra innings, whether you’re comparing them to regulation baseball or to visiting teams in extras.

Why is that? Defensive positioning and strategy is my best guess. When the visiting team faces a runner on third with no one out in a tie game in extra innings, they have no choice: They’re stranding that runner or the game is over. You can take a lot more risks with your back against the wall. You can pitch for strikeouts, intentionally walk hitters you don’t want to face, play the infield and outfield ridiculously close, try to throw out the runner at home even if it’s a long shot, or even bring in your best strikeout pitcher to tilt the scales in your favor. It’s not quite the same when you’re up a run, but teams are still willing to sell out to stop a run from scoring in that situation, far more so than in the top half of the inning or earlier in the game.

In fact, this aggressive defensive posture is nothing new. From 2010 through 2019, to pick a pre-zombie-runner sample, home teams were similarly inept at getting a runner home from third base in extra innings – or if you’d prefer, defensive squads were similarly good at preventing that run from scoring. The only reason it’s more noticeable in home field advantage now is because we’re seeing these situations more often. In the old days, getting a runner on third base with no one out in extra innings was vanishingly rare, and getting a runner there with one out wasn’t exactly common. Now, it’s almost a given.

Said another way, home teams have always been at a disadvantage, relative to their regulation winning percentage, in extra innings. Mains’ research bears that out, and I’ve looked into it before with similar findings. That’s partially because of a situation where they’ve historically performed worse than the visiting team: scoring a runner from third with less than two outs. That situation happens more frequently now than it used to. It’s a classic unintended consequence – no one thought too much about home teams’ underperformance in these spots because it almost never came up. That imbalance just didn’t matter much without an automatic runner in place. Put someone on base to start the frame, though, and converting runners into runs starts to matter a lot more.

If you’re like me, there’s one thread still nagging at you. If defenses are so good at stopping runners from third from scoring, why don’t we see it in the results I quoted for home team winning percentage when the visiting team fails to score? It’s because we’re missing a variable: bunts.

See, home teams are less efficient at converting runners on third into runs, but in tie games, they get runners to third base with one out more frequently than you’d expect. They do so by bunting. Sure, Doan’s research found that teams weren’t bunting enough in extra innings, but it also demonstrated, far beyond the shadow of a doubt, that teams bunt much more than they do in regulation innings. Starting the bottom of a tied extra inning with a bunt is a winning play. It increases win probability meaningfully from a naive estimate. It just so happens that it increases win probability by enough that it offsets the subsequent challenges that the home team has driving that run home.

I find this puzzle fascinating. It just feels wrong that home teams have a disadvantage in extra innings, the very time when getting to see what your opponent did first should matter most. But as it turns out, home teams have always struggled, on a relative basis, to cash in “easy” runs in extras. The new extra inning rule creates more chances to cash in easy runs. Just like that, you end up with a mysterious outcome – home teams aren’t winning enough. The key factor that creates this counterintuitive home field disadvantage has been around for a long time. We just never noticed it before the zombie runner turned “Can you get that dude home?” from an extra-innings afterthought to a high-frequency challenge.

This article has been updated to correct the rate at which both home and away teams score with a runner from third, correcting an earlier transcription error.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Are there differences in pitcher utilization? When up a run in the 10th I imagine the road team always uses their very best RP, but does the home team when tied in the top of the 10th?

So I initially planned on that being part of this article, but the truth is that I had a really hard time actually teasing it out of the data. There’s a lot of controlling to be done to make the results unbiased (at least, I thought so when trying to do it) and I couldn’t handle it well enough to feel comfortable including it. If someone better than me at math wants to take a crack at it, let me know!

It probably can’t truly be done. I do think this is your answer, though: the road teams are probably using their closer/ace reliever to pitch the 10th more frequently than the home teams. These pitchers likely strike out more hitters than the average reliever, too, which is especially crucial with the ghost runner. If they can keep him at 2B after the first batter, the threat of a sac fly is neutralized, and the entire strategy of the inning changes.

This is the inherent issue with a runner starting on 2B: you can make three consecutive outs yet still score a run. I feel like we see more first-batter bunts from road teams than we do from home teams down by a run, as home teams don’t seem content to play for a re-tie and an 11th inning. While their run expectancy may be higher by not bunting, their frequency of scoring is likely a bit lower.

Is there a way to calculate the weighted average full-season stats of the pitchers who have pitched in the top of the 10th and compare it to the same calculation for the bottom of the 10th?

Both teams should use best pitcher available in tie games late and extras. If the home team does that less frequently it’s an unforced error

Well, actually, as we know, at home the “closer” typically pitches in the top of the ninth in a tie game, to hold things where they are and give his team a chance for the walk off. After all, it’s impossible for there to be a subsequent save situation in such a game. By contrast the road team usually doesn’t have their closer pitch the bottom of the ninth, preferring to hold him back for the possible save situation. To the extent the “closer” is synonymous with “the best pitcher” it might be interesting to see if in games tied after 8 innings, home team are doing better than might be expected in the ninth inning.

I’m not sure your assumptions about closer usage by the road team are still operative in 2025.

It probably depends on how rested the bullpen is (including the closer himself) and how many other good relievers they still have available as to when exactly the road team will use their closer in a tie game in the 9th inning and beyond.

Still, I’d imagine he’d be held off by the road team by at least an inning on at least some occasions.

Both teams should based on what exactly? If the home team is facing the bottom of the lineup in extras I’m more inclined to not use my closer there than in the next inning. There’s too many other factors at play to simply say the best reliever should always be used.

Hence the conundrum of extra innings as a home team, you don’t know what your team will have to do offensively to win the game prior to committing to which reliever you’re using in an extra inning.