The Moment Before the Moment

The thing about hype is it makes the expectations almost impossible to meet. Hype is what makes you excited for an event, but then it’s up to the event itself to live up to the billing, and the standards can be impossible. Game 7 of a playoff series? That’s a high bar. Game 7 of the World Series? Higher bar still. Game 7 of a World Series featuring the two teams with the longest active title droughts? The hype spirals out of control. The game couldn’t possibly be what you’d want it to be.

That game was what you’d want it to be. Even if you weren’t rooting for the Cubs, you might never see a better baseball game. Maybe you’ve seen games that were as good, but you couldn’t top that, not for the drama, and not for how very Baseball it was. It was a one-run game that went to extra innings. The winning pitcher was the world-class reliever who blew a three-run lead. The losing pitcher wasn’t even supposed to have to pitch. The Cubs jumped out against the Indians’ unhittable ace, who for the first time was left in too long. The Indians clawed back with a two-run wild pitch that got by a catcher inserted specifically to help the pitcher on the mound. That same catcher, who’s now retired, then hit a home run off one of the only relievers who might be better than the Cubs reliever who later blew the save. Both teams used starters in relief. There was a rain delay and a bunt for a strikeout. The last out of the game was made by Michael Martinez. The final go-ahead run was scored by Albert Almora.

Almora scored on Ben Zobrist’s double. That made it 7-6, and Cubs fans were once again able to breathe. In a game packed full of moments, that might have wound up the moment, the moment that set the Cubs on their course. Before that moment, there was a different one. Almora scored on the double. He first had to get himself into position to do so.

This is how a part of the inning summary reads:

Schwarber singled to right.

Almora Jr. ran for Schwarber.

Bryant flied out to center, Almora Jr. to second.

Rizzo intentionally walked.

Zobrist doubled to left, Almora Jr. scored, Rizzo to third.

That takes you from the start of the 10th to the lead. Kyle Schwarber singled, but Kyle Schwarber ain’t gonna run. He was replaced by Almora, and Almora quickly moved up. That led to the Anthony Rizzo intentional walk, and that led to Zobrist, and that led to a run. There’s nothing weird in here. On paper, this is a pretty ordinary baseball sequence. In practice, it was more extraordinary than it reads. Because this is how Almora advanced.

That’s an aggressive tag-up maneuver, and here you can have eyes on Almora the whole time:

In effect, it’s a stolen base, a stolen base that didn’t need for a pitch to be pitched. When the ball landed in Rajai Davis‘ glove, the Cubs had a 50% chance of winning. After Almora arrived at second, that jumped up to 57%, and then the Rizzo walk pushed it to 59%. That’s pretty much all Almora, a rookie who didn’t know he’d be doing anything until the inning’s first at-bat. Almora had a moment, setting up the Ben Zobrist Moment. The Almora play was not the biggest one of the game. But it was a key contributor to the biggest sequence of the game. And so I want to review how the play came to happen.

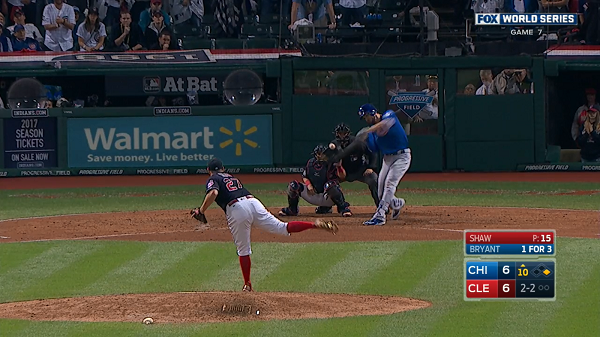

Almora doesn’t move without a Kris Bryant fly. There’s no Kris Bryant fly if there’s a Kris Bryant strikeout. This is the pitch before the fly, a pitch thrown in a 1-and-2 count. The pitch is located well, around two different edges, and based on some interpretations, you’d even occasionally see this pitch called a strike. I don’t say that to make Indians fans upset — this is mostly a ball. But it’s a quality ball, and Bryant took it. This post is about Albert Almora, mostly. But Bryant saw some close pitches. He earned his way to 2-and-2.

And that’s when Bryan Shaw wanted to go just off the plate. The idea was good. There’s usually nothing wrong with the ideas. It’s the execution that was lacking.

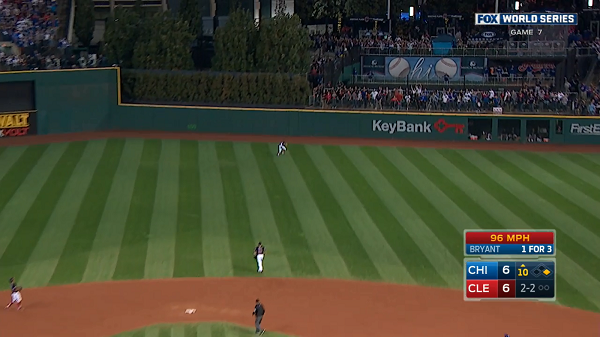

For what it’s worth, that is not a Kris Bryant hot spot. Though Shaw missed, he missed to a half-decent area, and Bryant usually makes substandard contact around there. This contact was technically substandard — Bryant hit into an out. But in doing so, he hit the baseball just shy of 100 miles per hour. I’m not a player, so I don’t know what 98 in the air looks like on the field, but I bet it doesn’t look too much different from 108. When Bryant hit the ball, I’m sure we all had the same immediate idea. Almora couldn’t have been immune.

Dexter Fowler homered around that area of the yard. David Ross homered around that area of the yard. You see Davis here in retreat, and in the broadcast booth, Joe Buck’s voice was rising. The ball was going at least to the track, and if a ball is going at least to the track, it could easily be going beyond it. Albert Almora was just into the game. If this ball bounced off the wall, he could score the go-ahead run in Game 7 of the World Series.

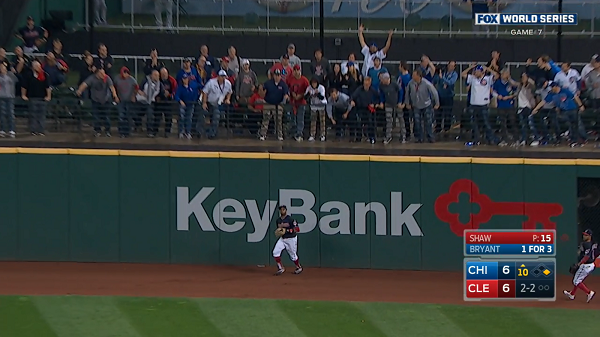

You see some arms up. By this point, Davis was camped underneath the ball halfway through the track, but at least one Cubs fan in the area still had faith that something good could happen. The other Cubs fan looks like he just realized the ball was going to come up short. Hands over your head transition quickly to hands on your head. Still, these are people standing almost exactly where the baseball was hit. They weren’t quite sure what was going to happen to it. Almora had to make up his mind from hundreds of feet away.

And here’s where Davis made his mistake. To his credit, he did have to cover some ground to track the ball down. And when you catch a fly ball on the dirt, there’s not so much you can do in order to generate forward momentum. Plus, you know, Rajai Davis does not have a powerful arm. But the ball was caught too casually. There was no urgency, no immediate recognition that Almora might try to move up. Davis hesitated in returning the ball to the infield, and his return throw was neither strong nor accurate. What chance Davis really had, I couldn’t tell you, but he had a better chance than it looked. He either forgot about Almora, or he didn’t expect to be tested. Almora made the right read the whole way.

That’s Almora when he started back to first base. That’s Almora when he knew he’d have a chance to tag up. There are some outstretched arms in the crowd — to them, this was a fly ball that still had potential. Almora saw it for what it was, and he ignored the urge to see it for what it wasn’t. The broadcast never showed a split-screen of Almora and Davis at the same time, but based on timing I did with a stopwatch, Almora started back when Davis was just getting onto the warning track. These aren’t easy plays to research; there’s no database of fly balls and baserunning that’s easy to query. I don’t know how many baserunners would’ve done what Almora did. It was certainly nothing unprecedented. But Almora read that the ball was hit too high up. He could’ve easily gotten over-excited, running down to second just in case the ball found the wall. He kept himself in check, electing to be differently aggressive.

Of course, it takes a village. Shown here is Bryant, who’s realized he just missed a go-ahead homer. But there’s also Jason Heyward, telling Almora to advance. And there’s first-base coach Brandon Hyde, who’s probably said the same thing. Hyde might’ve taken a moment to review the Indians’ outfield arms when Almora came in. I don’t know who deserves the most credit for Almora tagging up — I’m going to guess it’s Almora himself. Yet he might’ve heard his coach, or he might’ve heard his bench. That is, if he could hear anything. He might’ve heard nothing but the pounding within his own chest.

If the throw were on the money, it looks like it would’ve been close. If Davis hadn’t hesitated, maybe, just maybe, Almora’s out. This was part read and part speed, but this wouldn’t have been possible had Almora gotten further out on the basepaths after the ball left Bryant’s bat. It was an exercise in restraint, where it would’ve been easy to excuse a runner for getting ahead of himself. Almora wasn’t thinking about the glory of a run. He was thinking about turning Bryant’s negative into a positive. As Bryant felt his own disappointment, Almora made his fly out productive.

Gotta make sure you stay on the base.

Don’t want to be the guy who comes off of the base.

If you scroll back up and watch the videos, you can see Francisco Lindor try a little something. He tried to apply a quick tag to Almora’s foot, and he was too late. Then he wheeled around as if to throw the ball, then he wheeled back around to try a quick tag again. It didn’t work, and it didn’t come close to working, because Almora didn’t move, content to be where he got to. It was like replacement-level trickery, Lindor hoping Almora would step off if he thought Lindor threw the baseball somewhere else. I don’t know if that play has ever worked. Might as well try it, though. There was no cost, and Lindor knew of Almora’s importance, out there in scoring position. Almora knew the importance of being in scoring position, too. That’s why he ran to get there.

Albert Almora isn’t the hero. He didn’t make the biggest hit, nor did he make the biggest play. He’s one of few Cubs who might have to say who they are if they want a free drink. Given all the moments from an unforgettable Game 7, some moments will have to be forgotten; some will just slip through the cracks. Maybe, some months from now, they won’t be talking about the one-out tag-up. But that was the moment that set up the Moment, the moment the Cubs’ fortunes started to turn. Kris Bryant might’ve just missed a pitch he wanted to hit, but thanks to a good read and aggressive base running, Bryant’s fly out still put the Cubs on course for a World Series title. They say that it had been a few years.

Jeff made Lookout Landing a thing, but he does not still write there about the Mariners. He does write here, sometimes about the Mariners, but usually not.

Jeff, have you slept yet?