The Nationals Try Something Entirely New, Clinch NLDS

The ball left Justin Turner’s bat at 70.3 mph, with a launch angle of 34 degrees. Per Statcast, batted balls with that exit velocity, hit on that plane, have an expected batting average of .550. A little better than a coin flip. There were two out, and nobody on base, and Sean Doolittle on the mound; there were thousands still left at Dodger Stadium willing the ball to fall, thousands more in the empty stadium in Washington praying for it to find a glove. The Washington Nationals had a 99.9% chance of winning the game. And also, Michael A. Taylor, out in centerfield, sprinting toward it — at the last moment, stretching out his glove — the ball, barely missing the ground, centimeters from escaping his glove.

Had the ball fallen, it barely would have made a difference. The Dodgers’ win expectancy would have improved to something like 0.5%. But that’s not what it felt like. Not for the Dodgers fans who had remained through the preceding disaster, looking for a sliver of hope, the slightest graze of cowhide against grass. Not for the Nationals fans, hoping for something they hadn’t yet seen — a glove closed around a ball for a series-clinching out, an end to the years of futility, the beginning of something completely new. This is where the postseason takes you: Years of your life, untold amounts of time and emotional energy spent, seeming to rest in the inches between a ball and a glove and a few blades of grass.

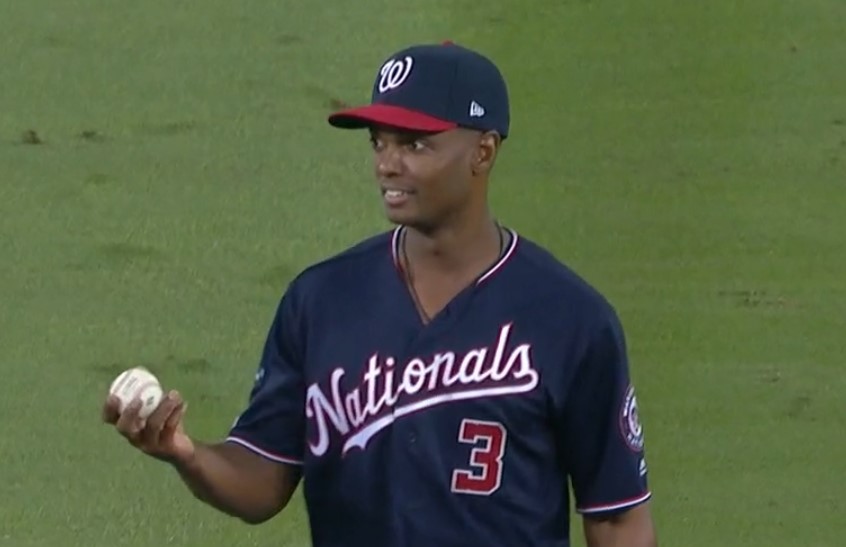

Taylor rose up and took the ball in his glove, a confused expression on his face. Turner, on the basepath 200 feet away, motioned to the dugout. But even as the game hung, for a few moments, in the purgatory of umpire review, the fans knew, and Sean Doolittle knew, jumping off the mound and into the stratosphere, and Adam Eaton knew, leaping in from right field. It was over. The Washington Nationals had won Game 5. They were advancing to the NLCS. And the Dodgers’ historic, 106-win season had ended. They were nine games too short, nine innings too short. A few runs, a few pitches, maybe. A few inches. Sometimes cliches are cliches because they’re true.

***

The game began with Walker Buehler striking out Trea Turner on a 97 mph fastball, just like he had to open Game 1. Buehler retired the side on just 10 pitches in the top of the first, looking for all the world like the dominant starter who had held the Nationals to just a single hit over six innings last Thursday. It was the opening the Dodgers had hoped for.

And in the bottom of the first, they got the opening they had hoped for from the bats, too: a resounding double from Joc Pederson to lead off the game against Steven Strasburg — a double that, due to some wall-padding ambiguities, seemed for a moment to be a home run — and a home run from Max Muncy, around whom the Dodgers offense this series has turned. In Game 2, Strasburg carved up the Dodger lineup to the tune of 10 strikeouts over six innings of one-run mastery; within five minutes, the Dodgers had shed the weight of that poor performance, handing Strasburg his first-ever postseason home run. Leading off the next inning, Kiké Hernández, making his first start of the series over the beleaguered A.J. Pollock, sent a ball just barely over Michael A. Taylor’s outstretched glove.

For the three innings that followed, the game settled into a rhythm. Strasburg settled down — after the bottom of the second, Cody Bellinger was the only batter to reach base against him. Buehler didn’t have quite as much control as he did in Game 1 — the first turned out to be the only inning in which he didn’t allow a baserunner — but rarely seemed to be in distress.

An exception to this came in the top of the fifth. Buehler allowed a leadoff walk to Kurt Suzuki and a single to Michael A. Taylor, putting the tying run at the plate for the Nationals. That tying run came in the form of Strasburg. Instead of pinch-hitting for him, though, Dave Martinez left him in, unwilling to trade a better plate appearance for a few extra innings of the Nationals’ turbulent bullpen. Strasburg struck out on a full-count foul bunt, failing to move the runners, and Buehler retired Trea Turner and Adam Eaton to end the inning. The threat was over.

In another version of this game, that first out given to the Dodgers might have been a critical decision point in their favor, a blunder by Dave Martinez that cost the Nationals their best opportunity to score. As it turned out, it was just a footnote.

***

Buehler ran into trouble again to start the sixth. Facing the heart of the Nationals order, he quickly gave up a double to Anthony Rendon and a single to Juan Soto, putting Washington on the board. He remained in the game, though, and managed to coax a double-play ball from Howie Kendrick. (This, of course, prompted sarcastic comments about Kendrick’s status as the Dodgers’ NLDS MVP; his three errors accounted for all the errors made by the Nationals in the series.) He made it through the sixth without allowing another baserunner.

Still, it was clear that Buehler was no longer working at peak capacity. This was back-to-back innings where the first two Nats batters had reached. Now, every runner on base brought the tying run to the plate. With a well-rested bullpen and a season on the line, one might have expected Dave Roberts to err on the side of caution.

Yet Buehler reappeared to start the seventh, with nearly disastrous results. A 94 mph fastball nearly hit Suzuki square in the face. Its impact was dispersed somewhat by his helmet, but Suzuki was still shaken. He lay on the ground, face-down, for several tense moments; eventually, upright but dazed, he left the game. Buehler, though, remained, despite the scare, despite the number of pitches he had thrown, despite the complete availability of the bullpen. He struck out Michael A. Taylor; pinch-hitter Asdrubal Cabrera lined out.

The lineup turned over. And, facing him for the fourth time, Buehler failed to retire Trea Turner. A walk put him on first, with the speedy Taylor at second, and Adam Eaton coming to bat.

Dave Roberts spoke before the game of his intention to have Clayton Kershaw “piggybacking” after Walker Buehler exited. He stuck to his plan. Kershaw took the mound to face Eaton. He struck him out on three pitches.

That moment — as Kershaw, he of the much-discussed playoff demons, walked off the mound, the lead intact, only six outs remaining between the Dodgers and the NLCS — was the loudest Dodger Stadium got all night.

With Strasburg now out of the game, Tanner Rainey and Patrick Corbin retired the Dodgers 1-2-3 in the bottom of the seventh.

***

Clayton Kershaw is one of the best pitchers of his generation. He has been a cornerstone of one of the most successful franchises of this decade. If people still read baseball history in the future, if anything of this sport remains, what will remain with those baseball historians of the future will be an impression of Kershaw’s greatness.

But Kershaw was not the best pitcher the Dodgers had to face Anthony Rendon and Juan Soto to open the top of the eighth. Kenta Maeda, over three and two-thirds innings in this series, had allowed just one baserunner, and struck out four of the 12 batters he faced. Adam Kolarek, whose one job in the series seems to have been to retire Juan Soto, had been successful all three times he was called upon to do so. There was no reason that Roberts needed to put Kershaw in to pitch the eighth.

Six pitches from Kershaw later, and the game was tied.

And if someone had been scripting this game, there could be no more fitting players to the Nationals’ tides turning but Rendon, the long-tenured superstar who had suffered through the disappointments of the past six seasons, and Soto, the Wild Card hero, the bombastic young phenomenon, the hope for the future. Rendon’s home run was a shot, a burst of energy; Soto’s home run was an explosion.

Another postseason failure to hang over Kershaw’s head — and this time, a completely unnecessary one. He should never have been in that situation. Roberts put Maeda in the game — too late. He struck out the next three batters. The Dodgers went quietly in the bottom of the eighth.

***

Joe Kelly appeared for the Red Sox in all five games of last year’s World Series. He pitched a total of six innings. He allowed zero runs. He allowed zero walks. He struck out 10 of 22 batters. He was, in a word, overpowering, an essential part of the Sox’s bulldozing of the Dodgers. This postseason, he once again played a critical role in the Dodgers’ demise.

It was surprising that Kelly came into the game in a tied ninth at all. Again, Dave Roberts had the pick of his bullpen. Kelly left his most recent appearance in Game 3 having allowed two runs on two hits and three walks without recording an out. Just nine out of the 22 pitches he threw were strikes. It’s hard to believe that, in the highest of high-leverage situations, Kelly was the best option available. The clean ninth he pitched was wrought with tension, like he was pitching it on borrowed time.

But with Eaton, Rendon, and Soto coming up to bat in the top of the 10th, out came Joe Kelly again. No sign of Kenley Jansen. No sign of anyone else. Eaton walked. Rendon doubled.

When the decision was made to walk Juan Soto, leaving the bases loaded with nobody out, and leaving Kelly to face Howie Kendrick? That felt like the game was already over.

***

The Washington Nationals have never won a postseason series. It’s been so often repeated that it’s almost axiomatic. They’ve come so close, so many times; they’ve had the best players having the best seasons, only to see their season frittered away by some cruel act of God, some failure so incredibly random and unpredictable that it seems to have had to be divinely ordained. Drew Storen in 2012, the wild pitch in 2014, the Jansen-Kershaw tandem in 2016, the bottom of the fifth in 2017 — there have been so many iterations of loss that it becomes difficult to imagine what victory could possibly look like.

As it turned out, it looks like this: Howie Kendrick, the veteran of over a decade somehow having one of the best seasons of his career, turning on an 0-1 fastball in the top of the 10th.

And it looks like Michael A. Taylor, holding out the ball, confusion on his face. Like when you’re a very little kid, and every time a ball is hit to you in a game it feels like the first time you’ve ever seen a baseball, and every time you catch it you can’t believe it. Your heart pounds, and when you look at your glove, and take the ball in your hand, you don’t expect it to actually be there. But there it is. There it is!

That is what the Washington Nationals winning a postseason series looks like. Who would have guessed? Who would have wanted to?

***

Five years ago, on episode 551 of the Effectively Wild podcast, ESPN’s Sam Miller said this:

“The point of this entire enterprise is to entertain us with baseball games. The point of it is not to decide who is the best team. The illusion that that is what we’re doing has long been a powerful draw to sports. But it is ultimately not the point. There is no scenario where the universe will care or remember who the best team was out of this collection of collections. It only matters inasmuch as we create this illusion that it matters.

If you lose even the illusion, then it becomes problematic. But the point is not to have the illusion: the point is to entertain people and make them forget that we are all dying right in front of each other — that this is just this horrible, rotten slog to rigor mortis, that we are going to lose everybody we know, that we are going to lose everything we have and the only way to distract ourselves is by separating our day into distractions.”

The Dodgers won 106 games this season — the most in franchise history. Now, like all but six of the teams in franchise history, they will head home for the winter without having won the World Series, the ostensible point of all this baseball-playing. That failure hurts. It hurts the players and staff of the team: that they didn’t manage to bring home a championship for their teammates, for their friends, for the fans who supported them. It hurts that they will never be able to win with this exact group of people, who they’ve spent so much time and gone through so many highs and lows with. And it hurts for the fans, the people who invest their hours and their money and their identity into this fantasy called a baseball team. The hurt is real, ridiculous though it might seem to people who aren’t invested. Talk to any player, any fan, and you will know it’s real.

The joy, for the winners, is just as real. Washington Nationals have now won a postseason series, and for the first time in the history of their franchise, they will be playing for the National League pennant. They might play for the World Series, too. More likely is that they don’t — that they, too, lose. Either way, like the Dodgers, they will go home, regroup. And they will come back next year, ready to do it all again. Ready to try to win. Ready to probably fail — to get hurt again.

If failure hurts so much, why keep doing it? Why keep coming back? Baseball is a game, after all. That’s the worst and best thing: It’s just a game. It is people’s livelihoods, people’s passions; it lifts families out of poverty. It is an unimaginably large business, a gross display of wealth. It exploits people. It brings joy to millions. It gives people purpose when they can find none. And it is a game, a frivolous entertainment played with a bat and a ball, where the difference between success and failure, between pain and triumph, is a few inches of leather, a few slivers of wood.

What an incredible thing, to will into existence so much meaning from something so small. To feel pain, to feel it acutely, and know that it will end — to be able to believe that there’s always next year, always another team or another player, always another chance for things to go right, always someone who will get their win in the end, and that they will deserve it. Life has no such guarantees. But baseball isn’t life. Baseball is just a game.

And so another season ends for the Dodgers, and a season doesn’t end yet for the Nationals, not this time. They will celebrate, and then they will get ready. The NLCS starts on Friday.

RJ is the dilettante-in-residence at FanGraphs. Previous work can be found at Baseball Prospectus, VICE Sports, and The Hardball Times.

“This is where the postseason takes you: Years of your life, untold amounts of time and emotional energy spent, seeming to rest in the inches between a ball and a glove and a few blades of grass.”

Just caught me right in the feels, Rachel. And I have no investment in this series.

Also, a note: the ball that hit Suzuki hit his wrist, not his face. The ball ricocheted into his helmet, and knocked it off, but did not hit him directly in the face.

that was a really strange play with Suzuki- definitely looked worse in real time than it did when you saw the replay.