The Platoon Split You May Have Never Heard Of

Writing about baseball isn’t the most predictable task. I often don’t know what my topic will be until the dust settles, hours after rummaging through a pile of numbers that, at first glance, makes little sense. For example, this article started off as an inquiry into Darin Ruf. Of all the journeymen to stop by the KBO, experience a resurgence, and return stateside, he’s by far enjoying the greatest success – who would have guessed?

As a right-handed hitter, Ruf’s primary asset is a knack for mashing lefty pitchers. He can hold his own against righty pitchers, too, posting a 126 wRC+ against them last season. But detractors might point to a .386 BABIP that buoyed much of that production. In other words, one could expect Ruf to become a bit more… rough in the future (sorry). A quick search reveals that he had a higher groundball rate against righties compared to lefties, which doesn’t bode well for future success, and not much else. The critics win this round.

Here’s the thing, though – he wasn’t alone. It turns out that in 2021, right-handed hitters had a higher groundball rate against right-handed pitchers; conversely, they had a lower groundball rate against left-handed pitchers. You can see for yourself:

| P Throws | vs. RHH | vs. LHH |

|---|---|---|

| Right | 43.4% | 41.4% |

| Left | 41.1% | 47.5% |

This is also true of left-handed hitters. Facing same-handed pitchers led to more groundballs, while opposite-handed pitchers led to, well, the opposite. The gap in groundball rate by pitcher handedness is greater for lefty hitters, though that may be influenced by the relatively few instances of lefty-versus-lefty matchups. Still, the difference, which appears on a league-wide scale, is significant enough to warrant an investigation.

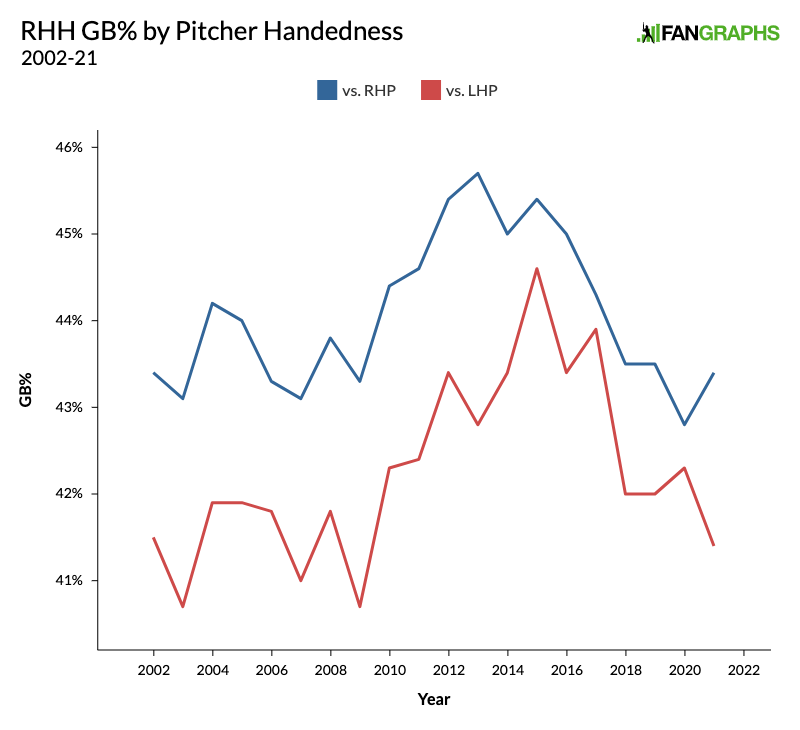

So, what’s causing it? Just a fluke season, perhaps? Not really, because you could observe this trend in the pandemic-shortened 2020 season, too. Ditto the year before that. And if we keep going back, all the way to 2002, the first year batted ball data is available at FanGraphs, this is what we see. First, the righty hitters:

Then, the lefties:

Yep, it’s a similar story. This weird, obscure, yet entirely real divergence has been around for at least two decades, and there doesn’t seem to be prior research on the subject.

Maybe we can figure it out. Consider the different types of pitches hitters encounter, depending on the opposing pitcher’s handedness. Righty pitchers are more likely to offer righty batters breaking balls that swerve away from the barrel of the bat, in hopes of inducing weaker contact or whiffs. Against lefty batters, however, those same pitches swerve into the bat’s sweet spot – not good! It’s why righty pitchers will bring out their changeup against lefties, and why the development of one is still seen as a prerequisite for becoming a starter.

The idea: Pitchers tend to approach same-handed and opposite-handed batters differently, and this habit is driving the discrepancy in groundball rate. To test it, I scraped together every pitch put into play in 2021 – excluding bunts, because ew – and looked at the pitch type distributions (fastballs, breaking, offspeed) for each possible batter-pitcher matchup (e.g. RHH vs. RHP). Here’s the rough distribution of pitches that righty hitters put into play last season:

| P Throws | Total | Fastball% | Breaking% | Offspeed% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right | 45,885 | 59.3% | 33.6% | 6.8% |

| Left | 26,102 | 58.1% | 19.3% | 22.4% |

Followed by the lefty hitters:

| P Throws | Total | Fastball% | Breaking% | Offspeed% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right | 37,942 | 56.8% | 21.5% | 21.5% |

| Left | 9,824 | 62.3% | 32.6% | 4.7% |

These numbers aren’t jarring at first glance. More breaking balls versus same-handed batters? Sure. An offspeed bonanza instead against opposite-handed ones? Yeah! But keen readers might have spotted something peculiar. Offspeed pitches like changeups tend to generate low launch angles when put into play; it’s no surprise that they’re the preferred offering of soft-contact champions like Logan Webb and Framber Valdez. Yet confusingly, it’s the same-handed batter-pitcher matchup – which features an abundance of breaking pitches, not offspeed – that’s responsible for the higher groundball rate. That doesn’t add up. What gives?

There’s another pitch famous for creating grounders: sinkers. They’re here to provide us with a better answer. It’s obscured under the all-encompassing fastball label, but when sinkers are isolated, we can observe another handedness-based trend. Against same-handed hitters, pitchers have a slight tendency to throw more sinkers:

| P Throws | vs. RHH | vs. LHH |

|---|---|---|

| Right | 17.6% | 12.4% |

| Left | 15.0% | 18.6% |

And it seems like pitchers do so to gain an advantage – in 2021, for example, righty-on-righty sinkers returned a .341 wOBA on contact and a two-degree launch angle, whereas righty-on-lefty sinkers returned a .390 wOBA and an eight-degree launch angle. Digging through lefty pitcher splits and prior seasons returns similar numbers. Throwing sinkers to same-handed hitters is, without a doubt, the safer option. Tying this back to our investigation, that lower launch angle in tandem with an uptick in usage likely outweighs the effects of the offspeed pitches opposite-handed hitters receive. Moreover, unlike with sinkers, offspeed pitches don’t really have a launch angle split based on handedness. Righty-on-righty offspeed pitches averaged seven degrees; lefty-on-lefty ones averaged nine in the same year. Here’s a table that sums it all up:

| P Throws | vs. RHH | vs. LHH |

|---|---|---|

| Right | 2 | 8 |

| Left | 6 | -2 |

But that last detail makes this all the more confusing, and honestly, I’m stumped. Movement-wise, sinkers and changeups are extremely similar, with the latter dropping an extra few inches. Maybe minor differences in pitch shape are responsible, but that doesn’t seem like a satisfying conclusion. There are also count- and location-based factors to consider: Sinkers are used to nab strikes early in the count, while changeups are usually seen as an out pitch. And while sinkers can also thrive up in the zone, for the most part, changeups end up down and away – just where you would expect. Further research is required, no doubt.

It’s also interesting to consider how this ties into the notion of platoon splits. When watching a righty batter hit a moonshot off a feeble lefty, we might be inclined to think that contact quality is the most prominent aspect of a platoon split. But according to research from Baseball Prospectus, it’s the tendency for batters to strike out less and walk more against opposite-handed pitchers, rather than a metric like slugging percentage, that’s sticky year-to-year. Platoon splits, it seems, are a matter of plate discipline.

I’d argue, though, that the groundball rate split is nearly as important as the strikeout or walk rate split. It might not be consistent among individual players, but collectively, the league has long had an easier time elevating against opposite-handed pitchers. Righty hitters last season had a .184 ISO against lefty pitchers, a number that dwindled to .161 against righties. It’s roughly the distance between Mike Yastrzemski and Aaron Judge, all because of those pesky groundballs.

That in and of itself isn’t a seminal discovery, of course. But I’ve yet to come across an article that discusses platoon splits in terms of a discrepancy in groundball rate, which seems to be caused by… sinkers? Maybe this isn’t the most relevant subject, but the mystery of it all is fascinating enough for me. At this point, I pass the baton onto whoever stumbles upon this, granting them full permission to yell at me in the comments for omitting this or that. Same-handed batter-pitcher matchups result in a higher rate of groundballs. I have no further updates about major league baseball’s lockout.

Justin is an undergraduate student at Washington University in St. Louis studying statistics and writing.

i’d imagine a right on left changeup (for example) is relatively more likely to get a whiff whereas a right on right changeup is relatively more likely to induce a groundball and vice-versa. to what extent (if at all) could this explain the higher gb% that we see when the pitcher has the platoon advantage?