The Playoffs Aren’t Too Big. The League Is Way Too Small.

With the first 12-team postseason in MLB history right around the corner, we’re hearing a little bit of griping. The playoffs, like your dad’s hand-me-down sport coat, are too big. Look at the race for the last Wild Card spot in the NL, in which the Phillies and Brewers have spent the past two weeks bumbling around like a pair of somnambulant dachsunds investigating a cricket. Eventually one sneezes and forgets what he was doing in the first place, and the other gets tired and plops over for a nap. The cricket escapes unharmed. Surely these are not playoff-quality teams. Surely they’re nothing but an inconvenience to a champion-elect like the Dodgers. But they’ll get a full three-game audition nonetheless. What a waste of time.

And by and large, I agree. While the current playoff structure seems to incentivize regular-season competition and could lead to some exciting October action, all things being equal I’d rather go back to an eight-team playoff bracket. Maybe because that’s the way things were when I was a kid, which is the overriding logic behind about 95% of people’s opinions about baseball, art, or society at large, but that’s how I feel.

But go back and consider, for a moment, that hand-me-down sport coat from your dad. You’re a teenager, fresh off a growth spurt, all tendons and hormones. The jacket, made for a man, looks weird on the frame of what is essentially a very tall child. But the problem is not that the jacket is too big; it’s that you are too small. On a bigger person, with a more fully developed frame, it would look just fine.

So while a 12-team playoff is probably too big for a 30-team baseball league, a 30-team baseball league is preposterously small for the size of the audience it serves. America, like Leon from Airplane, is getting larger. MLB should do the same.

The thing about humanity is: There’s a lot of us, and we keep reproducing. That’s as true in the U.S. as it is anywhere else. The Census Bureau estimates that there are some 333.2 million Americans at the moment; a new American is born every nine seconds, a new American immigrates every two minutes and change. Accounting for death rate, we net a new person every 25 seconds.

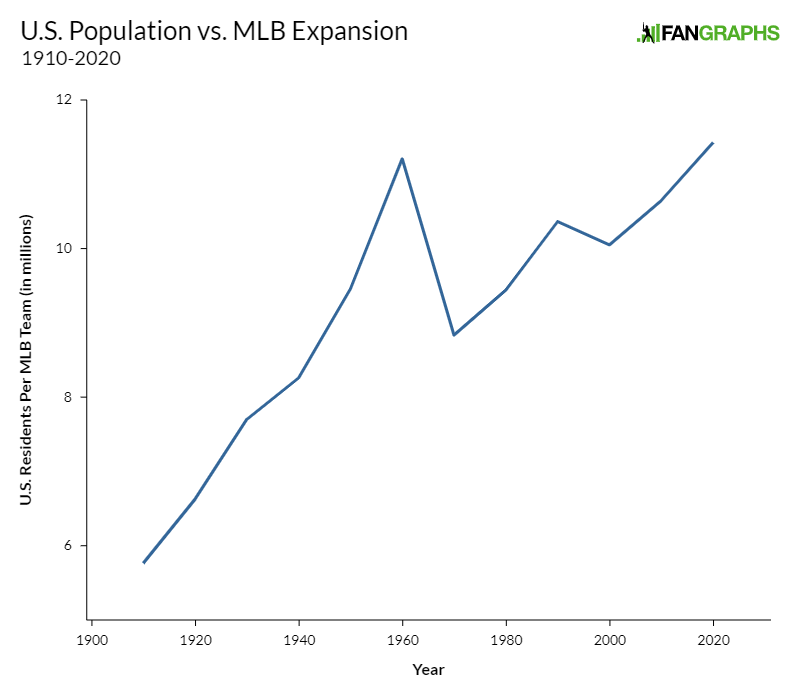

MLB, however, hasn’t added a new team in the U.S. since 2005, and even that — the relocation of the Montreal Expos to Washington — involved borrowing a franchise from Canada. It’s been almost 25 years since the league expanded, and in that time the U.S. population has grown by more than 20%. Mid-decade census data is an estimation, but using the government’s hard population data at the start of each decade since 2010, we can see that there have never been more Americans per American MLB team.

In 2020, there were 11.42 million Americans per MLB team, the highest that ratio has ever been. In fact, the only time the ratio had ever broken 11 million people per team was 1960; MLB expanded for the first time the following year and added seven teams in the U.S., plus the Expos, in the following decade.

The first census after the formation of the modern AL-NL duopoly, 1910, registered just 5.76 million Americans per MLB team. This was a massive overstatement. The two leagues would not fully consolidate their control over professional baseball until the 1950s; in addition to upstarts like the Federal League, the International League and Pacific Coast League were among the organizations that ran de facto quad-A competitions in cities unserved by MLB, to say nothing of the Negro Leagues, which were every inch a major league back then but not recognized as such by MLB until 2020. (For whatever that’s worth — which, considering the records and financial windfall Black baseball leaders lost thanks to segregation, isn’t a lot.)

The appetite for baseball was once insatiable. Then again, back in those days there was no NBA, no soccer to speak of, and the NFL and NHL were a shadow of what they are now. No TV, no internet — just a nation of children so bored they thought ball-in-a-cup games were solid entertainment. Did our society pass baseball by, or did baseball fail to meet the demands of an expanding nation?

After two decades of stasis and after watching every competitor expand to great success, serious people are once again talking about embiggening the league. Where should these new franchises go? Serious contenders include Portland, Charlotte, Nashville, Las Vegas, maybe Vancouver or a return to Montreal.

To this I say, “yes.” Don’t stop at 32 teams. A 12-team playoff is still too expansive for a 32-team league.

But not for a 48-team league. Yes, 48.

Add them all. Stick another team in Southern California. Put two more in New York. New Orleans, Virginia Beach, Jacksonville, Austin — put a chicken in every pot, a car in every driveway, and an MLB franchise in every U.S. city of half a million people or more. And from there, expand to Mexico City, San Juan, Santo Domingo — the “America” of the American League could be North America, not just the United States. Baseball, from sea to shining sea.

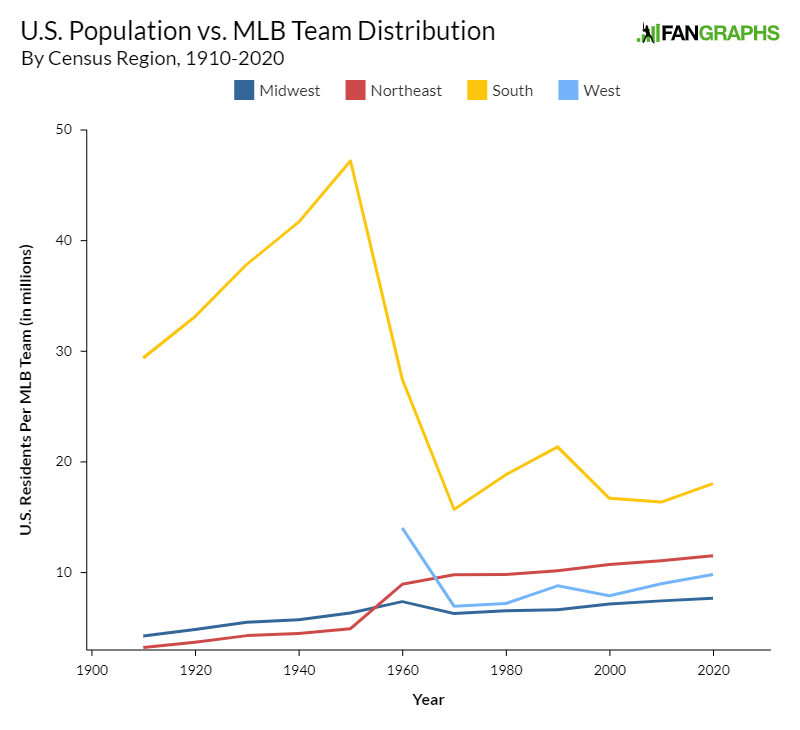

There was a time when MLB followed demographic trends, most notably in the rapid reorganization and expansion of the 1950s and 1960s that brought MLB to the South and the West Coast for the first time. As Americans migrated across the continent, emboldened by highways, air conditioning, and cheap land, baseball followed, to a point. The West Coast is now as thick with MLB teams as the league’s traditional homestead, but one region remains underserved: the South. The Census Bureau, conveniently, splits the country up into four regions for statistical purposes, and you’ll find that one just doesn’t get as much pro baseball as the others.

As jarring as that trend line is to look at, the figures are even more skewed than they seem. The Census Bureau defines “the South” quite broadly. Pennsylvania is in the Northeast, but Maryland and Delaware are in the South for census purposes, dividing the Crab Fries Belt right down the middle. (“Euh neu!” cried millions of distraught Philadelphians, Baltimoreans, and Wilmingtonians upon finding out they’d been cut off from their neighbors.)

But to the point: Until 1962, the only MLB teams in “the South” were situated in Baltimore and Washington. Even now, there are two teams in Texas, two in Florida, and only one (the Braves) to serve the rest of the region up to Washington, D.C. Among states that host an MLB club, the top three in residents per team are Texas, Florida, and Georgia.

| State | Residents Per Team (in millions) |

|---|---|

| Texas | 14.57 |

| Florida | 10.77 |

| Georgia | 10.71 |

| New York | 10.10 |

| Michigan | 10.08 |

| California | 7.91 |

| Washington | 7.71 |

| Arizona | 7.15 |

| Massachusetts | 7.03 |

| Pennsylvania | 6.50 |

| Illinois | 6.41 |

| Maryland | 6.18 |

| Ohio | 5.90 |

| Wisconsin | 5.89 |

| Colorado | 5.77 |

| Minnesota | 5.71 |

| Missouri | 3.08 |

| District of Columbia | 0.69 |

Surely it’s a coincidence that this part of the country is the greatest stronghold for football, and for college baseball — a coincidence and not, say, the result of more than 100 years of neglect. Whether a team in a mid-sized Southern city could support a $250 million dollar payroll is an open question. (And based on what we know about the Braves’ finances, the answer might surprise you.) It’s also irrelevant. Baseball teams are so profitable because they are civic institutions, and people will identify with a local team if they feel like it represents them and makes them proud. Not to put too fine a point on it, but this explains the why the Cardinals are what they are, and the Pirates are what they are.

The idea of a team as a civic institution exists in Europe, in the world of soccer, even more than it does here. And their teams, rather than a collection of 30, are an ecosystem of dozens or even hundreds. People still come out to support the local team, to live and die with their fortunes, even if the range of potential outcomes is quite limited by our standards. The Rays and Guardians make the playoffs every year and they sometimes feel like a lost cause; second-division teams in England that will never ever win a title draw tens of thousands of fans a game. Could a team in Louisville or Charlotte or Greenville (pick a Greenville, any Greenville) draw like the Yankees? Charge TV rights fees like the Yankees? Spend with the Yankees? Of course not, which is why the current 30-team model is so successful, so defined by parity, and not dominated by teams from New York and California. But it could still attract fans and build a loyal audience.

In order to get invested in a team for which a championship is vanishingly unlikely, a fan needs to learn to define success on the team’s own terms. For the Yankees or Dodgers, it’s World Series or bust. For the Rockies, maybe making the playoffs is good enough. For the hypothetical Nashville Party Buses or Texarkana Smokers, it’d be about finishing over .500, or even the team just giving a good account of itself in defeat.

But Americans are told from birth that our civilization is exceptional, and that we, by extension, are exceptional, and that individual success comes from hard work and moral rectitude. Winners finish first; everyone else has something wrong with them. For a variety of reasons, ranging from tanking to hot take discourse to the polarization and commercial exploitation of fan culture, the championship-or-bust attitude is more pervasive now than ever. Can a baseball team that wins infrequently build a devoted following? Yes, but maybe not here and now. Defeating that attitude means finding happiness where one can, redefining success to account for structural obstacles. These attitudes would be a welcome corrective to a culture that’s all too frequently cutthroat and unforgiving.

The most practical argument against radical expansion stems from the structure of MLB as an organization. Despite its legally enshrined exemption from antitrust law, it is not a monopoly but a cartel, and the distinction is important. A monopoly would be incentivized to expand as much as is practicable; if you already own the entire market, the only way to make more money is to increase the size of the market. If MLB were a monopoly, it would be doling out franchises like they were Chick-fil-A storefronts. But it is a cartel, which means that insofar as it’s out to promote “baseball” as such, it does so only insofar as promoting baseball enriches the 30 individuals or syndicates that own a franchise.

We see this all the time in disputes over how moving a club would impact local TV markets; Orioles-Nationals and Giants-A’s are two prominent examples. Owners are similarly defensive about expansion. Want to know how lucrative membership in this cartel is? The NHL’s Seattle Kraken had to cut the other 31 owners a check for $650 million in order to join the league on top of the startup costs of building a new team. Charlotte FC paid a $325 million expansion fee to join MLS. I’ll say it again: $325 million! For MLS!

The current owners, who give MLB and Rob Manfred their marching orders, have no intention of cutting that many new members in on a share of the pie, no matter how much demographics evince a market for new baseball. “The owners won’t like it” might prevent a hypothetical expansion plan from coming to pass, but it’s not an argument against the idea itself being sound. When Larry Baer starts whining about his territorial rights, “Who cares?” is an acceptable rejoinder.

These business incentives are only immutable as long as no one questions their validity. To give up on wanting or hoping for something simply because capitalism says it’s impractical strikes me as a joyless and unimaginative approach to thinking, living, and desiring. We can and should hope for exciting things, especially if they’re unlikely to happen.

Michael is a writer at FanGraphs. Previously, he was a staff writer at The Ringer and D1Baseball, and his work has appeared at Grantland, Baseball Prospectus, The Atlantic, ESPN.com, and various ill-remembered Phillies blogs. Follow him on Twitter, if you must, @MichaelBaumann.

“The most practical argument against radical expansion” from the point of view of fans (not the people who would make the decision) is that there are already so few good teams. Saturday I was deciding what game to watch and noticed that of the 15 games on, only 3 were between two teams with winning records. I don’t have the statistical firepower to calculate how many games in, say, all of September were between winning teams, but it sure seemed like not many. During the “crucial” playoff “races”!

How many of the 18 new teams would be happy to coast along at 71-91, believing/knowing that the novelty of being Major League Baseball in Vancouver will be enough to keep fans paying for tickets and beer? You know, like the Rockies.

And, of course, we can’t say that the solution is to find a bunch of new owners who love baseball and want to watch their teams win, because there are already 30 owners and only like 10 of them meet that description.

EDIT: Man, this sounds like I woke up on the wrong side of the bed. It’s a really good article! The historical data you assembled is really interesting and persuasive! I’m just a pessimist.

I think that the most practical argument is that with more teams, there would be longer droughts between championships for each team.

Like in Hockey, as soon as there were more than six teams in the NHL, it became impossible for the Toronto Maple Leafs to win a NHL championship.

I suppose with expanding the playoffs to keep it stable as a percentage of teams, people might focus on playoff droughts rather than just championships, but even with a sport with as much parity as baseball (no repeat winners since 2000, much more parity than the NFL), going from 30 to 48 teams would make it even less likely for any fan that their favorite team would win one in their lifetime.

The Red Sox, Giants, and Cardinals have all won multiple Championships since 2000. Your basic point of having much more parity yet still not enough for such rapid expansion is still accurate, though.

No team has won in consecutive years, some teams have won more than once in the entire 22 year span.

You didn’t say “consecutive.” You said “repeat,” which could mean either consecutive or multiple times overall. I mistook which definition you meant.

That wasn’t about how many teams were in the NHL, it was about Howard Ballard.

“Good” is relative. Right now there’s such a high level of shared talent and a degree of parity that it’s incredibly difficult for teams to separate from the pack.

Now, imagine MASSIVE expansion. MLB goes to 60 teams. Aaron Judge and Jacob deGrom are still who they are, but now there are Another 800 or so MLB players kicking around who ordinarily would have no business being in prime time. This is, essentially, the college football model. There would be enormous talent disparities between the top and the bottom of the league. Records would fall left and right. There would be 10+ teams with 100 wins, and someone would probably threaten 120 every year. Compared to the dross at the bottom, some of these teams would look “good” indeed.

But would they really be?

So, we’d create a new environment for the second comings of a new Babe Ruth and Walter Johnson?

Isn’t “good” always relative?

i think that sounds awesome actually

Until the 1960’s, we had 16 MLB teams, yet, the early 1950’s are some of the lowest parity seasons in history. Despite decades and decades of baseball since the expansion boom, many records from pre-expansion still stand.

In addition, you cannot extrapolate the current talent pool to what it would look like post-60-team-expansion. With more opportunities to make good money as a player, more viable athletes would stick with the sport instead of leaving the minors to be real estate agents. With a larger market of customers, more places like Driveline would pop up to help with player development. And so on – markets adapt to changing environments.

Finally, baseball talent is not distributed linearly. Doubling the talent in the majors, even with today’s current talent pool, does not mean that a 60-team-replacement-level-player would be half as valuable as the 30-team-replacement-level player.

Ironically, the number of games on any given day that will be between teams with winning records is directly correlated to number of teams that there are, and will stabilize around 1/4. This is simply a probability calculation. So if you want more options between teams with winning records, you actually need more teams, not fewer.