The Rarest of Gems for Syndergaard

NEW YORK — “It’s probably more rare than a perfect game, I’d guess,” said Mets manager Mickey Callaway on Thursday afternoon. “To hit a homer and win 1-0 with a shutout, that’s got to be one of the rarest things in baseball.”

Callaway was speaking of Noah Syndergaard’s two-way tour de force against the Reds at Citi Field, and he was correct. Dating back to the 19th century, major league pitchers have thrown 23 perfect games, the most recent on August 15, 2012, by the Mariners’ Felix Hernandez against the Rays. By the most generous count, just nine other pitchers have accomplished what Syndergaard did, the last of them the Dodgers’ Bob Welch on June 17, 1983, also against the Reds.

You don’t see that every day.

“Awesome,” said the 26-year-old Syndergaard when informed that he’d accomplished something that hadn’t been done in 36 years.

Awesome is a good description for Syndergaard’s complete performance on Thursday. In an afternoon game that might have benefited from a getaway day mindset for both teams as well as home plate umpire Marty Foster, the fireballing righty summoned his dominant form for the first time this season, striking out 10 while yielding just four hits and a walk. He augmented that with his second home run of the season, a 105.2 mph, 407-foot opposite field shot off the Reds’ Tyler Mahle in the third inning. Roll the highlight reel:

“He was a one-man wrecking crew out there today. That was a really awesome outing for him,” said first baseman Pete Alonso, who watched from the bench until pinch-hitting in the bottom of the sixth inning. The rookie, who leads the team with nine homers, said of Syndergaard’s shot, “He absolutely demolished that ball.”

Via the Baseball-Reference Play Index, YES Network researcher James Smyth, and Retrosheet, here’s a look at Syndergaard, Welch, and company:

| Player | Date | Tm | Opp | IP | H | BB | SO | GScV2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harry McCormick | 7/26/1879 | Syracuse Stars | Boston Red Stockings | 9 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Tom Hughes | 8/3/1906 | Senators | Browns | 10 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 80 |

| Gene Packard | 9/29/1915 | KC Packers (Fed Lg) | STL Terriers | 9 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 88 |

| Red Ruffing | 8/13/1932 | Yankees | Senators | 10 | 3 | 2 | 12 | 102 |

| Spud Chandler | 5/21/1938 | Yankees | White Sox | 9 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 80 |

| Early Wynn | 5/1/1959 | White Sox | Red Sox | 9 | 1 | 7 | 14 | 92 |

| Jim Bunning | 5/5/1965 | Phillies | Mets | 9 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 89 |

| Juan Pizarro | 9/16/1971 | Cubs | Mets | 9 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 86 |

| Bob Welch | 6/17/1983 | Dodgers | Reds | 9 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 76 |

| Noah Syndergaard | 5/2/2019 | Mets | Reds | 9 | 4 | 1 | 10 | 94 |

The two performances outside the range of the Play Index, which goes back to 1908, are both noteworthy, in that McCormick is the only pitcher who hit his homer in the first inning, and Hughes the first to hit his in the 10th, a feat later matched by Ruffing; both were in the top half of the inning, so alas, no walk-offs. Packard’s came in the short-lived Federal League. Bunning’s outing was less than a year after he no-hit the Mets, who had been on the wrong end of two such games, while Pizarro, the other pitcher to thwart them, is the only pitcher on this list besides Syndergaard who’s still alive (he’s 82). According to Tom Tango’s Game Score 2.0, which credits or debits a pitcher based upon the various items in his line score, Syndergaard’s performance rates as the best of the nine-inning ones, surpassing Wynn’s dominant but rather ugly one-hitter.

His outing could hardly have come at a more opportune time for the slumping Mets, who entered having lost five out of seven to fall to 15-15, tied with the Braves for second in the NL East, two games behind the Phillies. Through Wednesday, their vaunted rotation ranked 13th in the NL in ERA (4.86) and just seventh in FIP (4.13) and WAR (2.4). Their shaky bullpen (14th with a 5.53 ERA, 13th with a 4.88 FIP, 11th with 0.1 WAR), had lost Jeurys Familia to the injured list due to a sore shoulder after he blew a save on Tuesday night; on Wednesday, closer Edwin Diaz surrendered a ninth-inning homer to Jose Iglesias for the game’s only run. “We don’t know how we get through the rest of the game if [Syndergaard] doesn’t complete it,” said Callaway, later adding, “The lack of relief was a relief today.”

Syndergaard felt his own sense of relief with his 104-pitch performance, saying, “I felt like I was pretty close to rock bottom. I feel like a weight has been lifted off my shoulders.” He had entered carrying a 6.35 ERA, having allowed fewer than four runs only once in six previous turns this year. His 3.71 FIP was certainly more presentable, though nearly a run higher than his career mark; underlying it were career-worst walk and home run rates (6.8% and 1.3 per nine, respectively), offset somewhat by a 26.4% strikeout rate, which was at least better than last year’s career-low 24.1%.

After his previous start, in which he’d been cuffed for 10 hits (two homers) and five runs in five innings by the Brewers on a 50-degree evening at Citi Field featuring 24 mph winds, he’d struggled to get a feel for his pitches; allegations that he had used a foreign substance, based upon a video of him digging his right index and middle fingers into the heel of his glove, circulated. “You felt those baseballs, they felt like ice cubes,” Syndergaard told reporters in response while refusing to answer the charge. “Watch a video of a dog trying to pick up an ice cube, that’s what it was like.”

On a sunny 66-degree afternoon, Syndergaard didn’t struggle for feel, and he tore through a lineup that not only entered hitting .210/.284/.376 for a 71 wRC+, with three players carrying a 41 wRC+ or worse, but was without slumping first baseman Joey Votto. The big righty set the tone by striking out the first two hitters he faced, overpowering Jesse Winker on a 99 mph heater right down Broadway and inducing Eugenio Suarez to chase a curveball in the dirt. He got ahead of nine of the first 10 hitters he faced, and 24 out of 31 for the afternoon. Only once, on his third-inning walk of Suarez, did he even reach a three-ball count, and he never needed more than 13 pitches in an inning. The four hits he surrendered were all singles, to Derek Dietrich in the first and ninth innings, Jose Peraza (an infield single) in the second, and Suarez in the sixth; Dietrich’s second single was the only hit he allowed on the five balls with an exit velocity of 95 mph or higher.

The Reds never had two men on base at the same time, and only in the second inning, after Peraza had been erased via a double play, did a second batter reach in any inning; Syndergaard followed the twin killing with an error when a high-bouncing Scott Schebler comebacker glanced off his glove. Not until pinch-runner Michael Lorenzen, running for Dietrich in the ninth, stole his first career base did a Red reach second base. Syndergaard reached two-strike counts 15 times, and converted those into outs all but once, on Peraza’s hit. It was an utterly stifling performance.

Stuff-wise, Syndergaard generated 14 whiffs, six of them with a four-seamer that averaged 98.9 mph according to Brooks Baseball, a velo matching his season high. He touched 100 with both his four-seamer and his sinker (100.4 with the latter, his high for the day). Of his 10 strikeouts, eight were swinging, three via four-seamers, two apiece via changeups and sinkers, and one via a curve. Additionally, he froze two batters looking at high-velocity sinkers — a pinch-hitting Votto in the eighth and then Yasiel Puig for the final out of the ninth.

The ninth inning featured some additional drama, when Winker was ejected for arguing about whether a 97.2 mph sinker on the high outer corner of the plate was legitimately strike two (the Brooks map says it was); manager David Bell was tossed, too. Kyle Farmer was brought in to finish the business of striking out, though the K was charged to Winker.

Mets 1 – Reds 0

The Headline: Just Smile and Wave Boys…Smile and Wave

1?? Thor became the 1st pitcher to toss a 1-0 shutout via his own home run since LAD's Bob Welch in '83

2?? Inject Jesse Winker's ejection into our veins ???The GIF: pic.twitter.com/4STT1PFrVv

— Justin Birnbaum (@JustBirny) May 3, 2019

For what it’s worth, the Brooks strike zone map says it was the Reds who benefited more from Foster’s zone, though Syndergaard did his part to expand the outside edge against both lefties and righties.

Syndergaard attributed his return to dominance on cleaner mechanics and a simple plan of attack: “Just putting trust and conviction in every pitch, trying to win every pitch.” As overpowering as his fastball was, the key to his afternoon may have been the renewed use of his curveball instead of his slider. He threw 16 curves, his highest total since last September 2; he had thrown just 40 in his previous six starts, accounting for a career-low 6.8% of his repertoire. While the pitch, which averaged 79.2 mph, generated just two swings and misses, he used it to get five called strikes and a foul ball as well. His seven sliders was his lowest total in any outing of longer than five innings since April 20, 2017. Callaway, the former pitching coach, couldn’t stop talking about the value of the curve:

I’d like to see all of our pitchers incorporate [the curve] more, especially with the power stuff we have. Anytime you can change speeds and have a differential that these guys can have with their curveballs, it makes things so much harder and the thing that happens is that you become more efficient with your pitches and you’re able to throw a complete game… because they don’t foul off as many pitches. When everything is 90 to 97, you’re talking about everything coming in hard and guys can time that up a little better, even if it’s just to foul it off. So I think it adds a whole new challenge for the batter. You’re able to maximize your pitch count and go deeper into games and that’s what we want from our starters.

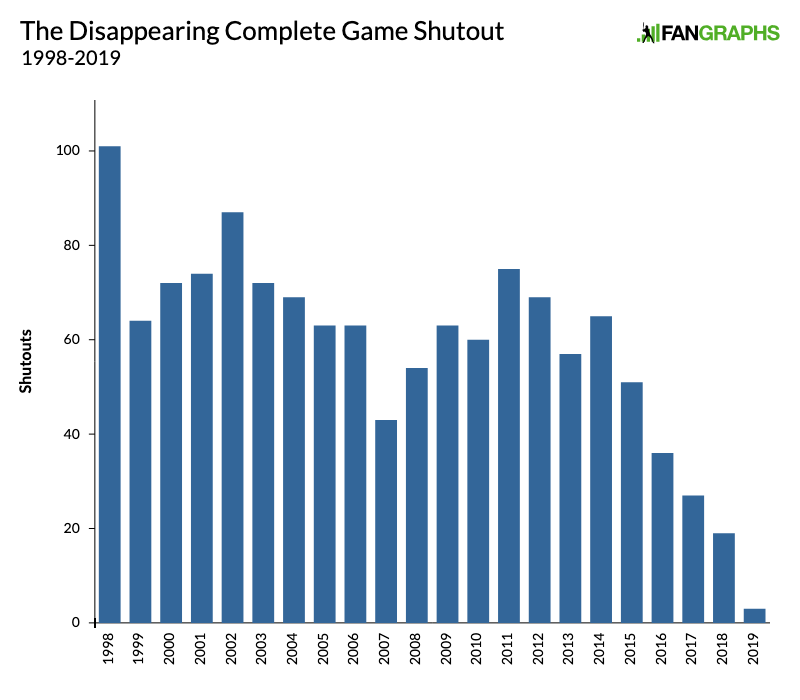

The shutout — as in the complete game variety, a comparative rarity itself — was just the second of Syndergaard’s career; he threw his first on September 30 last year against the Marlins, the final day of the season. It was just the third shutout in the entire majors this year; the Rockies’ German Marquez blanked the Giants on April 14, while the Rangers’ Mike Minor did the same against the Angels two days later. In an era of pitch counts and times-through-the-order concerns, the event has nearly gone extinct:

The majors are on pace for just 16 complete game shutouts this year, less than a quarter of the total of 65 from just five years ago. Even more rare than such outings are nine-inning games played in two hours and 10 minutes or less; Thursday’s was just the second of the season, after an April 24 game between the Padres and Mariners, while last year there were just four such games (including Syndergaard’s first shutout), with two in 2017 and seven in 2016.

All of which is to say that those of us who witnessed what transpired on Thursday afternoon at Citi Field — a crowd that looked far more sparse than the official attendance of 21,445, with a similarly scant showing in the press box — saw something incredibly rare and special, perhaps even better than perfect.

Brooklyn-based Jay Jaffe is a senior writer for FanGraphs, the author of The Cooperstown Casebook (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017) and the creator of the JAWS (Jaffe WAR Score) metric for Hall of Fame analysis. He founded the Futility Infielder website (2001), was a columnist for Baseball Prospectus (2005-2012) and a contributing writer for Sports Illustrated (2012-2018). He has been a recurring guest on MLB Network and a member of the BBWAA since 2011, and a Hall of Fame voter since 2021. Follow him on BlueSky @jayjaffe.bsky.social.

So with the exception of the fielders, he won the game by himself. That, my friends, is pretty cool. 10 strikeouts, 1 walk, 4 hits, no runs, 9 innings, 1 homer.

Backtest for the WAR checks out. He was worth 0.7 fWAR yesterday. We assume the WP for a replacement level player to be around .294.

I believe Pizarro actually makes the list twice, if you count shut outs in which the pitcher drove in all his team’s runs. The other time was not a 1-0 game. There have been a few of those, but not a lot, I think.