The Robo-Zone Could Make Catcher Defense More Valuable Than Ever

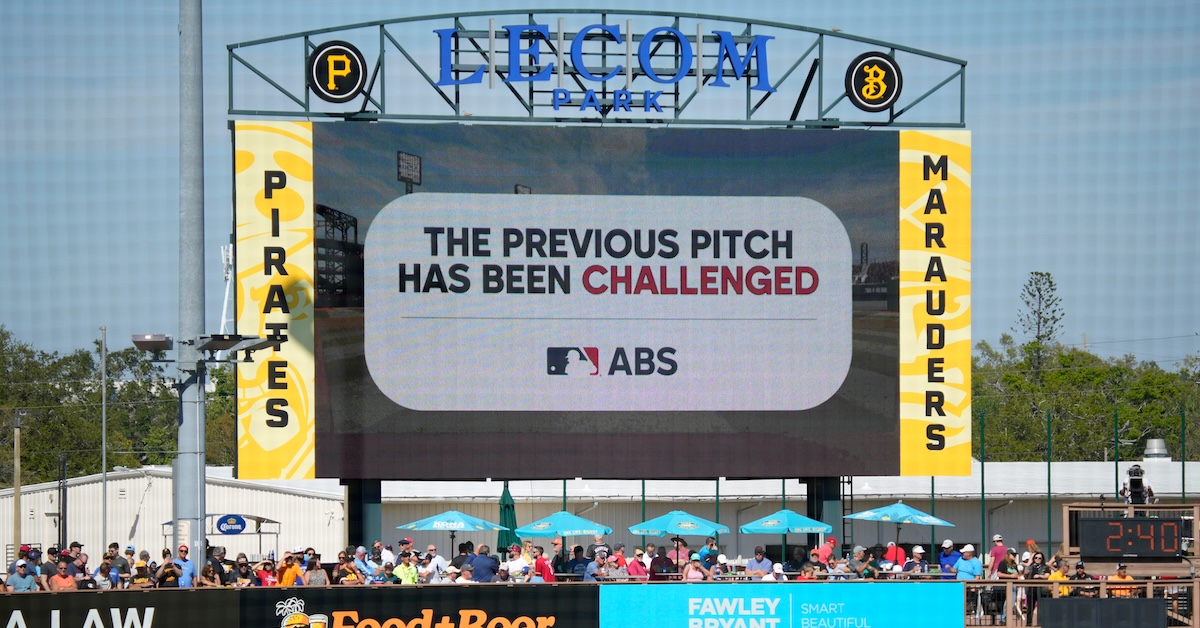

How much will the ABS challenge system hurt the ability of catchers to frame pitches? That question has been bouncing around my brain for quite a while now. I’d been waiting for the offseason to really dive into the numbers, and, well, we’re here. It’s the offseason. But now that I’ve dug into all the data I could find, I think the entire premise of that question might be flawed. I thought that correcting a couple of ball-strike calls a game would erase a couple of well-framed pitches. This would no doubt hurt the better framers more than it hurt the worse ones, simply because they earn more strikes and would have more to lose. At the same time, the lesser framers would have juicier pitches to challenge, boosting their numbers a bit. As a result, the gap between good and bad framers would shrink, furthering a trend that’s been going on since we first gained the ability to quantify the value of pitch framing. It would still be valuable, just not quite as valuable as it used to be. But I’m not so sure anymore. Let’s start with the data.

I pulled all the major league framing data I could. I pulled league-wide and individual catcher called strike rates both inside and outside the strike zone for the majors and for Triple-A, which in 2025 used the same challenge system we’ll see in 2026. I can tell you that 26 catchers got a significant amount of playing time in both Triple-A and the majors last season, and their called strike rate on pitches in the shadow zone in the majors fell by an average of 1.4 percentage points within the zone and 1.7 percentage points outside it relative to what it was in the minors. So while the Triple-A strike zone may be tighter, pitch framing is still harder in the majors. But the only data about how the challenge system has actually worked in the minors and in spring training of 2025 comes from MLB press releases, and it’s extremely sparse.

Of course, that data definitely exists. Baseball Savant guru Tom Tango wrote up a bunch of interesting takeaways from it on his blog a month ago. As you’d expect, players are more likely to challenge calls in higher-leverage moments, in the later innings, and on pitches that decide the outcome of an at-bat. For that reason, they tend to be less successful in those situations; they’re not challenging because they’re sure they’re right, but because they really want the call to go the other way. Tango also broke down some catchers and batters who were particularly good or bad at challenging. Not only did he provide their stats – poor Zac Veen challenged 24 pitches and got just three overturned – but Tango showed that Savant will be rolling out challenge probability numbers next year, using the distance from the edge of the strike zone to calculate the likelihood that any particular pitch will get challenged, and that any particular challenge will be successful. From there, it’s easy to calculate how much challenge value each batter or catcher creates above the average player.

All of those numbers will be really fun. We’ll be able to see whether catchers who are good at challenging while behind the plate are also good at it when they’re in the batter’s box. We’ll see how well plate discipline and framing value correlate with making good challenge decisions. We’ll get to see whether certain pitchers or kinds of pitches result in more challenges or more successful challenges. We’ll be able to answer our question about how it affects framing value! Right now, though, there’s not much to go on.

Here’s what we know so far. During spring training, 2.6% of all ball-strike calls were challenged, 4.4% by the offense and 1.8% by the defense. Eighty percent of spring games saw five or fewer challenges, and 52.2% of challenges were successful. Batters had a 50% success rate, while catchers were at 56% and pitchers were at 41%. Those last two numbers combined for a 54.4% overall success rate for the pitching team. Aside from the numbers for pitchers — which won’t matter much, as they’ve proven to be so bad at challenging that they’re already all but forbidden from doing so in the minors — all of those numbers are pretty close to 50%. In 2024, the Triple-A success rate was 50.6%. The league is understandably motivated to highlight that fact, to promote the notion that the challenge system won’t change the game all that much because everything will balance out. As a result, we’ve gotten quotes like this one from MLB executive vice president of baseball operations Morgan Sword: “In no strike zone that we’ve tried, in no format that we’ve tried, has the rate moved much above or below 50%, which is pretty interesting in that these are the subset of pitches that are most ‘controversial’ among players.”

All the same, those numbers don’t quite balance out perfectly, so let’s see how they would play out during the regular season if they held true. In 2025, Triple-A saw 4.2 challenges per game, which would work out to 10,206 total challenges over a major league season. Let’s say the percentages we saw during spring training hold up exactly. Batters initiate 59.1% of challenges and succeed 50% of the time, while defenders initiate 40.9% of challenges and succeed 54.4% of the time. In that case, batters would win 3,015 challenges, compared to 2,271 for defenders. That’s a net outcome of 744 extra balls, which works out to roughly 93 extra runs. Keep in mind that in the majors, umpires called just 236 strikes on pitches outside the shadow zone all year. Correcting those most egregious misses would be just a small part of the picture. In other words, the offense would come out way ahead, and those gains would largely come at the expense of pitch framers.

I’m not so sure those numbers will hold, though. As many people have noted, the Statcast zone is a bit tighter than the zone actual human umpires call, which would lead us to expect more called strikes. I’m specifically suspicious that batters will keep initiating such a high percentage of the challenges. A Reddit user named Avondice posted a couple of detailed breakdowns of the challenges from the 2025 Triple-A season. I reached out to ask where they got the numbers, and they said the data came straight from MLB’s pitch-by-pitch data. The breakdown showed an overall success rate of 49.5% — 45.1% for challenges by the offense and 53.5% for the defense. With a little algebra, we can reverse engineer from those numbers that 52.4% of challenges must have come from the defense, while 47.6% came from the offense. If those numbers were to hold in the majors, then the swing would go toward the defense rather than the offense. The net outcome would be 670 extra strikes, which translates to erasing roughly 84 runs.

Once again, I’m not sure how much to trust either of these sets of numbers. Neither spring training or Triple-A is exactly like major league regular season play. As I wrote last week, major league umpires are more accurate than minor league umpires, even without a challenge system to clean up some of their mistakes. They have far fewer big misses, and without that low-hanging fruit, regular season major league challenges might be significantly less successful than we saw during spring training (when pitchers are wilder and umpires are less accurate). Nonetheless, my point here is that even small differences can add up to a big number. None of these rates is all that far from 50%, just as Sword said, but that doesn’t mean they won’t have a big impact.

The other takeaway is that if we put challenges into their own category, separate from framing, then yes, the ABS challenge system will reduce the range of framing outcomes. But we could just as easily consider the challenge system part of framing. It’s still just a way of earning strikes, and I would remind you that framing isn’t just about stealing strikes on pitches outside the zone. Catchers are much more concerned with “keeping strikes strikes.” That is, making sure that when their pitcher hits the zone, they’re rewarded with a called strike. The best pitch framers in the league earn strikes on nearly 90% of shadow zone pitches in the zone, but outside the zone, that number is down below 20%. The challenge system will further reinforce that emphasis, and I’d remind you that in both of the sample sets we broke down, catchers ran much higher overturn rates than batters. Even if we sabermetricians split the leaderboards up into one category for framing and another for challenging, a catcher who’s great at both will be more valuable than ever! (As for whether those two skills are related, the tiny amount of data we have so far is inconclusive. Tango noted that Harry Ford was the worst challenger while P.J. Higgins was the best. Neither player looked like a great pitch framer this season.)

We’re only talking about a few overturned calls each game, and much of the time they’ll probably balance each other out; both teams pick up a call or two, the umpires gets yelled at a little less, and everybody wins. But that doesn’t mean things will even out between the offense and defense. If batters end up getting more value out of the challenge system, as they did during spring training, then catcher defense – the combination of framing and challenge outcomes – could take a real hit. The distance between elite framers and poor framers could shrink even further. But if catchers make more out of the challenge system, then the ones who can combine great framing with great challenge decisions could be even more valuable than ever, even if framing numbers take a hit.

Davy Andrews is a Brooklyn-based musician and a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @davyandrewsdavy.bsky.social.

I suspect where the greatest discrepancy lies between what we expect the strike zone to be and how it is called lies with batters of “outlier” heights. Not only your Aaron Judges, but also your Jose Altuves. As a manager, those types of players would be the only ones I’d really want using challenges as a hitter (except in special circumstances). We’ll see how it plays out, but if it’s anything like the basestealing rules, some players will go overboard, get the reins pulled in, teams will be too conservative initially until someone manages to nail the system.