The State of Spring Spin

With baseball’s time of game issue resolved (I say with just a hint of hyperbole), MLB’s battle with sticky substances is back to being a top priority for the league offices, or so we can gather from the latest league-wide memo on the subject. After the first crackdown mid-season in 2021, we saw a pronounced dip in spin rates and spin-to-velocity ratio across baseball, an apparent sign that pitchers were responding to the league’s concerns. When the league renewed its commitment to inspecting pitchers at the start of the 2022 season, this impact appeared to persist through the early spring. But as the season went on, it was well-reported that league-wide rates began to creep back up, nearing pre-crackdown levels by August of last season.

While in 2021, two pitchers were issued the 10-game suspension MLB had promised in the event of a transgression, there were no such violations in 2022, only this weird moment between Madison Bumgarner and umpire Dan Bellino and this high-profile ear massage for Joe Musgrove courtesy of Buck Showalter in the deciding game of the NL Wild Card Series. But the league has taken note of the elevated rates and now means business: umpires are being empowered to check pitchers randomly and at will, urged to increase their scrutiny in “frequency and scope.” The memo seems to say: “no, seriously, please stop doing that.”

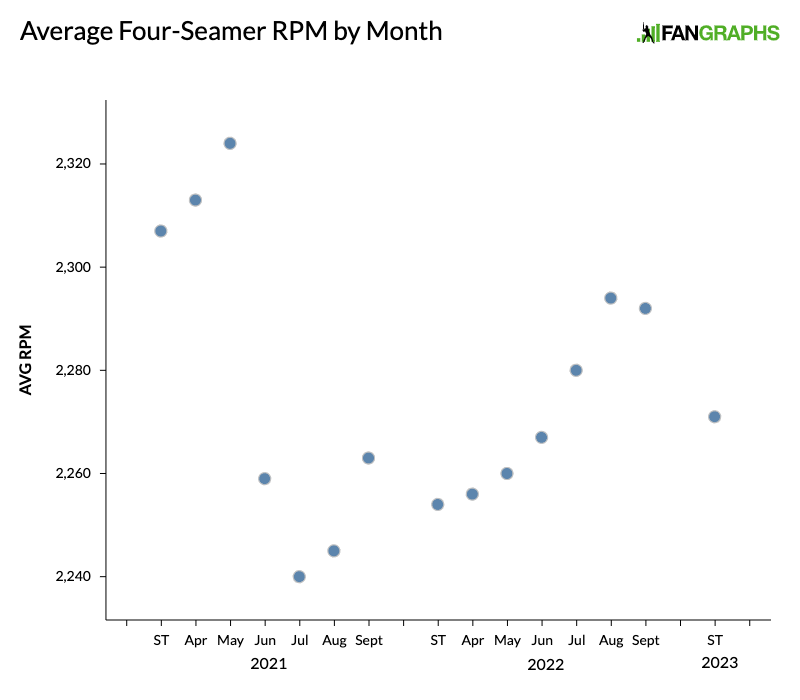

Given the league’s resurgent urgency on the matter, it’s worth checking in on where we stand this spring. Though Spring Training spin rate data is limited to games played in stadiums equipped with the technology to record it, that leaves us with a dataset that includes over 16,000 four-seam fastballs from all 30 MLB teams at 14 different Grapefruit and Cactus League stadiums as of Sunday. Those fastballs were delivered with an average of 2,271 rpm, 21 rpm lower than the league average in September and October of last season. It’s remarkable to think we even have the technology to perceive that difference — 21 rotations over a full minute is equivalent to less than a quarter of a rotation as the average fastball is traveling from the pitcher’s hand to the plate — but these are the types of indicators that are setting off red flags in the league offices. The league-wide increase observed from the opening month to August of last year that prompted the memo in the first place amounted to all of 38 rpm.

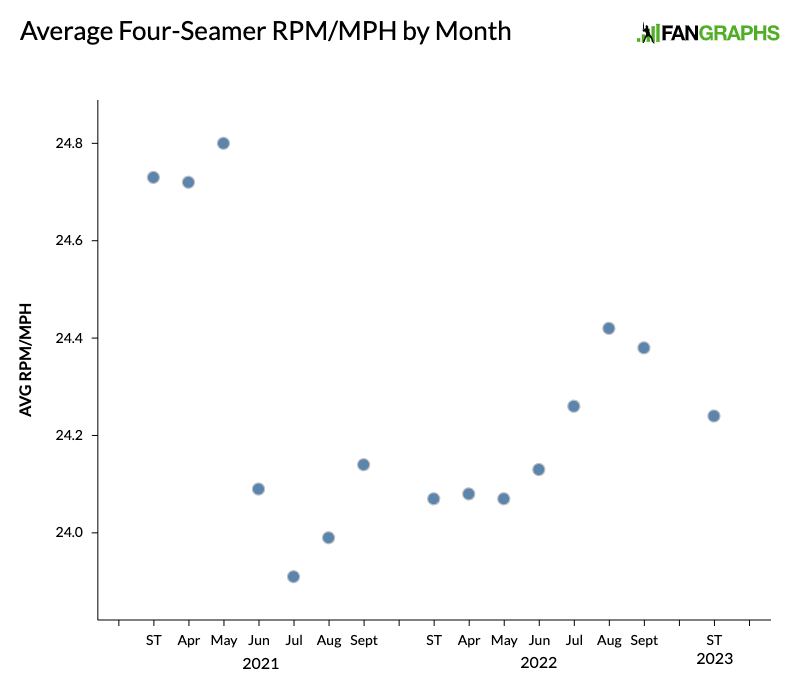

Here we can see the significant midseason dip in 2021, the incremental increase over the course of last year, and then this spring’s 21-rpm drop. But is this something we can expect to be reflected in the regular season or just a matter of Spring Training variation? Let’s take a look at the changes in spin rate with respect to velocity. Fastball spin rate and velocity have a strong positive relationship, as fastballs that are thrown faster also tend to spin faster. The average Spring Training fastball velocity is slightly lower than the average regular season fastball, so we would expect the average fastball spin rate to be lower as well. Looking at the change in the spin-to-velocity ratio instead of spin rate alone allows us to account for that in our analysis.

This chart has a similar shape; again, the drop in June of 2021 is profound, and again the rebound last summer is clear. And still, this spring’s fastballs trail those of late last year, down from 24.42 rpm/mph in August to 24.24 so far this spring. In other words, even given that this batch of fastballs is slightly slower on average, they’re also spinning slower per unit of velocity.

Now, as we would expect velocity to be slightly lower in Spring Training than in the regular season, we might also expect a lower spin-to-velocity ratio; presuming that the average major leaguer has a higher ratio than the average minor leaguer, we’d expect the league-wide average to dip when the deepest parts of teams’ depth charts are getting their reps in. In past years, we’ve seen some drop in spin-to-velocity ratio from the final month of the regular season to the following Spring Training, though this year’s drop is more pronounced.

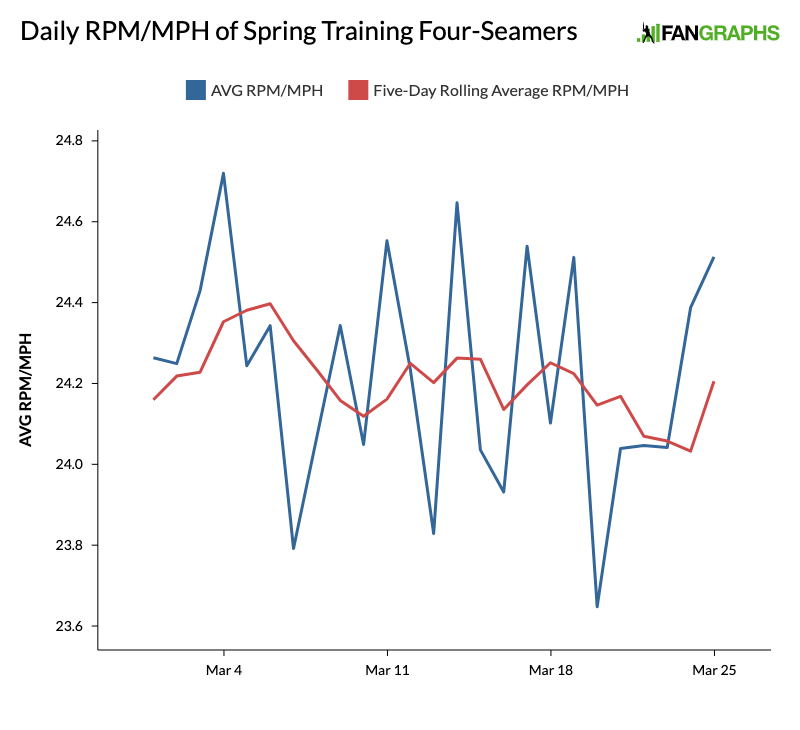

So what accounts for the more pronounced drop? This spring, as you may have noticed, a whole bunch of big leaguers (and minor leaguers) left for a couple of weeks to play in the World Baseball Classic, giving up more and more camp innings to minor leaguers and non-roster invitees. Could this have exacerbated any Spring Training effect on spin-to-velocity ratio? Let’s take a look at the rolling five-day average over the course of spring training to see if we notice any shift during the WBC:

Relative to our monthly data, this is a smaller data set: still several hundred fastballs a day, but small enough that the daily results are pretty volatile. If we look at a five-day rolling average, the peak value this spring, 24.4 rpm/mph, came on March 6, the day before the tournament started. Spin-to-velocity ratio then dropped down as low as 24.0 on March 24 before ticking back up over the weekend. This is less than conclusive evidence — there are a lot of moving parts involved in throwing 16,000 fastballs to try to attribute a shift to one thing or another — but the pattern above could suggest that the WBC has something to do with the degree of this spring’s dip.

Altogether, the difference in the groups of pitchers throwing this spring compared to last summer has me unsatisfied with comparing spin-to-velocity ratios as apples to apples. For a more direct comparison, there are exactly 300 pitchers who have registered four-seamers both last September (including the few regular-season schedule days in October) and in this year’s Spring Training. This group accounted for over 28,000 four-seamers in the last month of 2022 and, as of Sunday, have notched almost 10,000 this spring. Last year, the fastballs of those 300 pitchers had an average spin-to-velocity ratio of 24.350 rpm/mph, but this spring, that value is just a fraction of a hair up at 24.355 — effectively even.

The apples-to-apples approach suggests that this spring’s dip is in fact more related to the group of pitchers in the mix than anything else. But we’re also talking about Spring Training; there is both far less incentive to find the extra edge a sticky substance might provide, and far less consequence for doing so. The regular season, right around the corner, is a different beast, and come Thursday, all eyes will be on spin rates to see if the latest memo will have its intended effect.

My guess? The impact of the two suspensions from a year and a half ago has worn off, and if the league wants its memo to have teeth, it will be looking for more pitchers to make an example of early in 2023. If MLB isn’t issuing punishments for these sticky infractions, there’s little else it can do to have any control over the issue, and until pitchers fear consequences again, sticky stuff will find a way onto the ball. Buckle up for more intimate moments between pitcher and umpire; it’s only going to get weirder.

Chris is a data journalist and FanGraphs contributor. Prior to his career in journalism, he worked in baseball media relations for the Chicago Cubs and Boston Red Sox.

Better living through chemistry.

In any arms race nobody is going to willingly disarm. Instead, they find new “workarounds”.

If this was the case, spin would not have dropped a ton in 2021 when umps started looking for sticky stuff. League-wide ERA increased by 0.24 (average of cheaters and non-cheaters).

“The league-wide increase observed from the opening month to August of last year that prompted the memo in the first place amounted to all of 38 rpm.”

Isn’t the better question why we’re still pretending this even matters?

The league wants us to believe that less than one revolution over the flight of the baseball has such an outsized impact on quality of play that it requires some crackdown. Nobody wants to even bother questioning if that seems the least bit probable?

There were more balls put in play last August when spin rates returned to pre-crackdown levels than there were the previous August at peak crackdown.

Outside of a handful of anecdotal cases, where’s the evidence this really even matters to league-wide quality of play?

Elite fastball rise ~2018 or 2019 was average by the 2021 crackdown. Translated to inches, the average home run swing was a swing-and-miss 2 or 3 years later. That’s drastic

And yet we have zero evidence that fluctuations in spin rate have had any significant effect on overall swing and miss throughout the game.

This has been a failure to isolate variables; there’s clearly far more influencing state of play than spin rate or else we’d have seen results we expected from changes in spin. We have not.

Junk science.