The Velocity Surge Has Plateaued

Among the proposals exchanged by MLB and the MLBPA was the idea of studying the mound. More specifically, baseball is interested in studying what might happen were the mound to be lowered, or were the mound to even be moved back. In a sense, adjusting the mound might seem radical, but of course, the mound has been lowered before, and baseball wants to see if it might be able to combat the ever-increasing strikeout rates. The league-average strikeout rate in 1998 was 16.9%. A decade later, it was 17.5%. Yet a decade later than that, it was 22.3%. That’s a 27-percent increase in strikeouts over the course of ten years. You can see why people might want to nip this in the bud.

Why have strikeouts been on the rise? How might you explain all the swinging and missing? I suppose there are the people who might just grumble the term “launch angle” and leave it at that, but a more compelling explanation might be the league-wide increase in velocity. It’s been hard not to notice — as they say, now every bullpen has a half-dozen guys who come out throwing 95 miles per hour. Billy Wagner used to throw 96. Now everybody throws 96. And the less time hitters have to react, the more often they’re going to whiff. Case closed! We’ve all solved it, together.

Except for the part where velocity has ceased increasing. The velocity surge was something I think a lot of us just took for granted. Teams like velocity, and players are training harder than ever before. But the surge has slowed, if not stopped. You don’t need to dig too deep to find evidence.

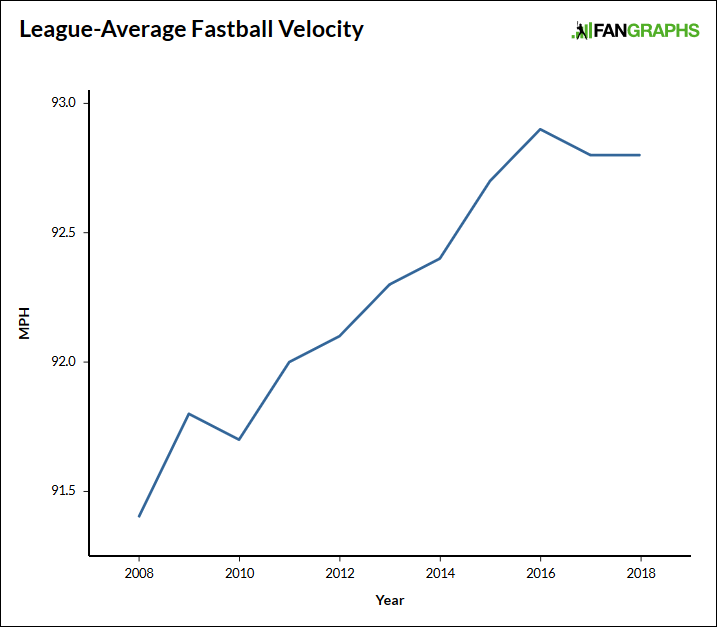

What follows is information from a few different sources, but I’ve done what I could to ensure across-the-board consistency. Let’s start in the obvious place — league-average fastball velocities, from 2008 through 2018, courtesy of Baseball Savant:

Even the surge itself is maybe not that eye-popping, when you look at it like this; from 2008 to 2016, the average fastball got faster by about a tick and a half. We’re not talking about everyone going from 85 to 95 overnight. Still, consider that the major leagues are selective for the most talented arms in the world. These are pitchers several standard deviations above the greater population mean. For upper-level fastballs to get faster by a tick and a half is pretty remarkable. But, since 2016: nothing. 92.9, 92.8, 92.8. The surge has flattened out.

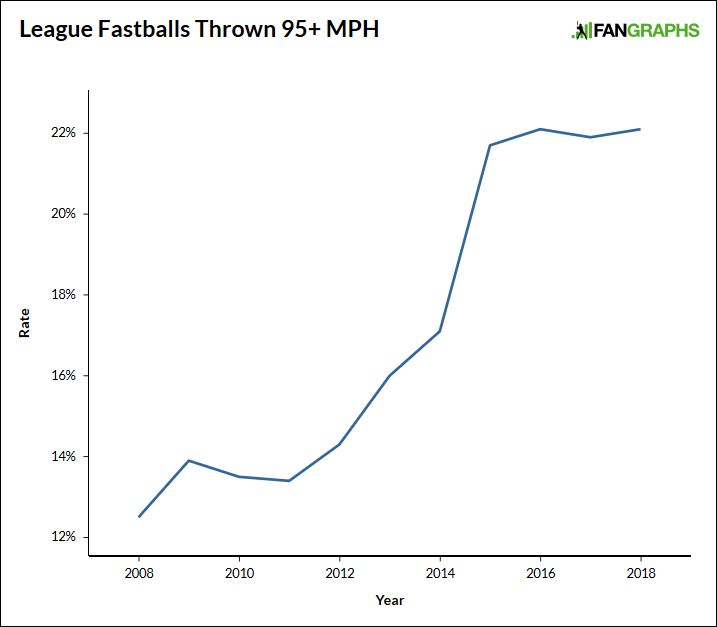

We can break this down in several other ways. Here’s a plot showing the league rate of fastballs thrown at least 95 miles per hour:

There’s a very steep increase, before the line levels off. You don’t see much movement between 2008 – 2011. Then, from 2012 – 2015, there’s an increase of more than eight percentage points. Then the recent flat bit. In 2015, 21.7% of fastballs were thrown 95+. In 2018, that rate held at 22.1%. Nothing doing over four years. It is, of course, relevant that there was also nothing doing over a four-year span a while ago, right before the real surge, but that doesn’t mean another surge is coming.

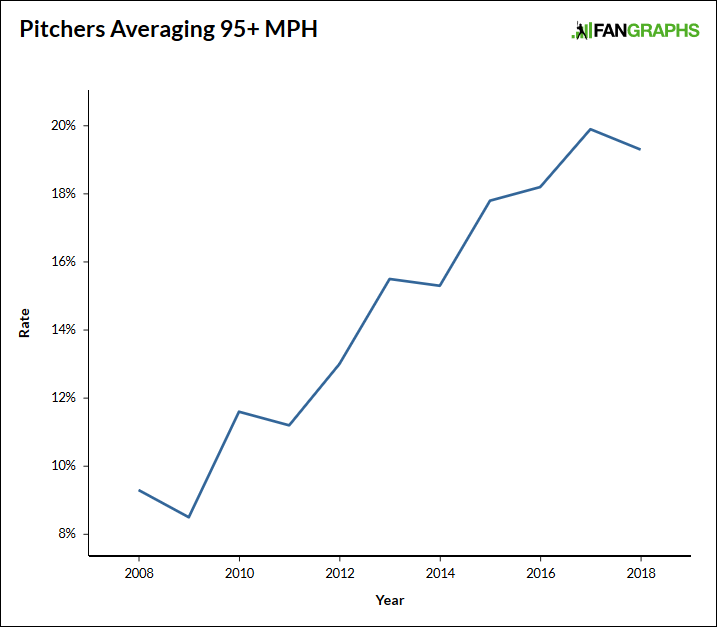

Related to the above, we can look at the following plot, showing the rate of pitchers averaging at least 95 miles per hour with their fastballs:

There’s a clear overall increase, even despite a few year-to-year drops. And that’s what we’re looking at in 2017 – 2018: a year-to-year drop. But, from 2015 – 2018, there’s an increase of just 1.5 percentage points. From 2012 – 2015, there was an increase of 4.8 percentage points. From 2009 – 2012, there was an increase of 4.5 percentage points. It can feel like everybody on every pitching staff throws 95 miles per hour. In reality, at least in terms of average fastballs, only about a fifth of pitchers qualify. That fraction has hardly budged of late.

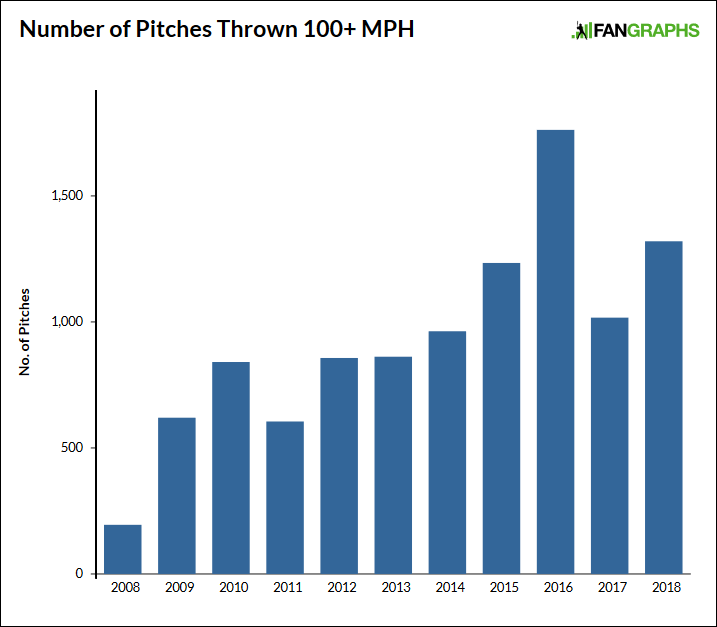

Switching to bars for a moment, let’s take a look at raw counting stats, for elite-level velocity. Here’s the league-wide number of fastballs thrown at least 100 miles per hour:

Last year had a greater number than the previous year, but it also had a lower number than the previous year. There hasn’t been much overall movement since 2015. Rare are the pitchers who can reach triple digits, and rarer still are the pitchers who can stay there without getting hurt. Some bodies just can’t train themselves to 100, even if the pitcher does everything right. We’re pushing up against certain physiological limitations.

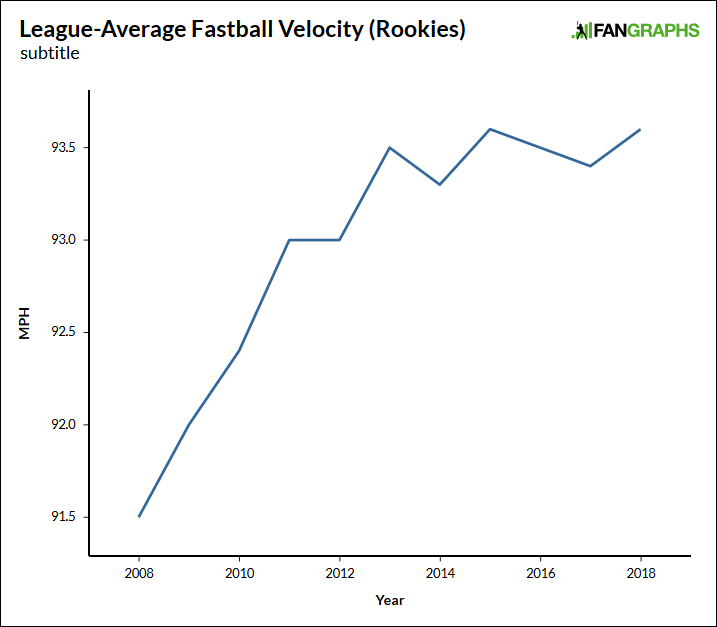

For one last plot, here are the league-average fastball velocities for rookies, and rookies alone:

As the league increasingly looks for velocity, you’d expect lower-velocity pitchers to be replaced by higher-velocity pitchers. You’d think that, in theory, baseball would be selecting for pitchers throwing harder and harder. But that’s not what the plot is showing. From 2008 – 2013, rookie fastball velocity increased by a full two ticks. And for six years, it’s held in the same place. Compared to 2013, 2018’s rookie velocity was up 0.18 miles per hour. That’s not literally *nothing,* but it’s nothing to write home about. Rookies aren’t all emerging from the minors throwing gas. Not, at least, at increasing rates.

The easy thing to do is to observe what’s already happened. In the past, we observed that there had been a velocity surge. Now, we observe that the surge has flattened out. It’s happened somewhat quietly, but I don’t know another way to interpret the data above. The hard thing to do is to forecast the future. Have we reached only a false summit, with another climb just in front of us? Or is this just going to be it? On the one hand, pitchers continue to train, and they continue to train hard. Teams everywhere are investing in tech, trying to find the keys to efficient biomechanics. Facilities like Driveline are becoming increasingly popular. On the other hand, a given human body can throw a baseball only so fast. Beyond a certain threshold, bodies stop working. We might well be approaching a point where major-league pitchers are throwing at almost 100% efficiency. And as much as teams might want to select for great velocity, great velocity doesn’t make one a great pitcher by itself. There have to be more considerations.

Every team could have a harder average fastball, if that was all they cared about. Every team has a bunch of hard-throwing young arms in the minors, and the reason they’re not in the majors is because they’re not ready. If there is to be another league-wide velocity increase, perhaps it might happen because teams figure out how to develop good mechanics more effectively. Maybe that’ll come out of all their new tech. It’s not yet something we can comfortably take for granted. For now, we can say that big-league velocity isn’t out of control. It seemed like it might be for a number of years, but pitchers can do only so much before they’re all doing as much as they can.

Jeff made Lookout Landing a thing, but he does not still write there about the Mariners. He does write here, sometimes about the Mariners, but usually not.

I really hope a study of the mound takes place in the near future. Seriously, who doesn’t like studies?

“who doesn’t like studies?”

I am not pleased to point this out, but I imagine that might be answered with demographics; among the sabremetric-minded community, perhaps relatively few, but among the general population, I might guess as much as 50% dislike ‘studies’, as that is approximately the portion who affiliate with organized religions which espouse beliefs and worldviews that are thoroughly incompatible with science, logic, rationality, and intelligence.

Wat

Although you maybe right, it’s a rather “heavy” response to a not so serious question

“Who does not like to learn?”

I’m glad you reported it, but I think we can respond to demographic data; Among the oriented communities, it can be relatively small, but in the general population, it seems that 50% do not like the “search”, and the behavior that relates to the religious organization that I recognize. Vera and Quiet are muscles that are not compatible with science, logic, reason, and intelligence.

I think we should really be talking about how that’s an incredibly long run-on sentence.

You trying to say that Jesus Christ can’t hit a curveball?

“You trying to say that Jesus Christ can’t hit a curveball?” LOL!!!!

u wot m8

The NFL doesn’t like concussion studies.

Perhaps someone should do a study of how many people like studies.

Are you sure that hasn’t been done already?