The Yankees Don’t Spend Like They Used to

After a season that saw the Yankees win 103 games, an AL East title, and get within two victories of reaching the World Series, Aaron Judge called the season “a failure.” Brian Cashman was a little more diplomatic, saying “we failed in our ultimate goal but we did not have a failed season.” If winning the World Series is the only path to satisfaction for a team, failure is almost inevitable. That hasn’t always been true for the Yankees and their 27 titles — even after going a whole decade without a championship, the Yankees’ five World Series wins in 25 years is still the most in the sport. Only the Red Sox, Giants, Cardinals, and Marlins have multiple titles in that time span, with eight franchises boasting a single title and 17 franchises without a ring since the strike.

The Yankees are often known for operating in another financial stratosphere. Forbes put a $4.6 billion valuation on the club, roughly 40% higher than the Los Angeles Dodgers and essentially the same as the White Sox, Mariners, and Blue Jays combined. While the Yankees’ YES Network is valued at around $3.5 billion, 14 other teams’ networks combined recently sold for about one-fifth that cost on a per team basis. Forbes estimates that only two teams (Dodgers and Red Sox) have annual revenues within $200 million of the Yankees. Financially speaking in baseball, there’s the Yankees up top, then 50 feet of swimming pools full of gold, then there’s everyone else. But lately, when it comes to spending on the major league roster, the Yankees haven’t operated as a behemoth and have instead opted to swim in that gold. Such is their choice.

The Yankees don’t have to spend like they used to in order to be successful. They’ve been better with player development, better at holding on to top prospects, better with trades, and better at identifying diamonds in the rough. Getting there cost them several years of playoff baseball, but they are coming off consecutive 100-win seasons, and though those teams didn’t win the World Series, they put themselves in position to have a really good shot. Strengthening the organization overall has allowed them to spend on payroll like they are a run-of-the-mill rich team. They could do more to win even more games and provide a better chance at a title, but it is difficult to know how great the motivation is to do so when they are already winning a lot. It’s also hard to put into perspective just how much they could be spending when they have one of the top payrolls in the game.

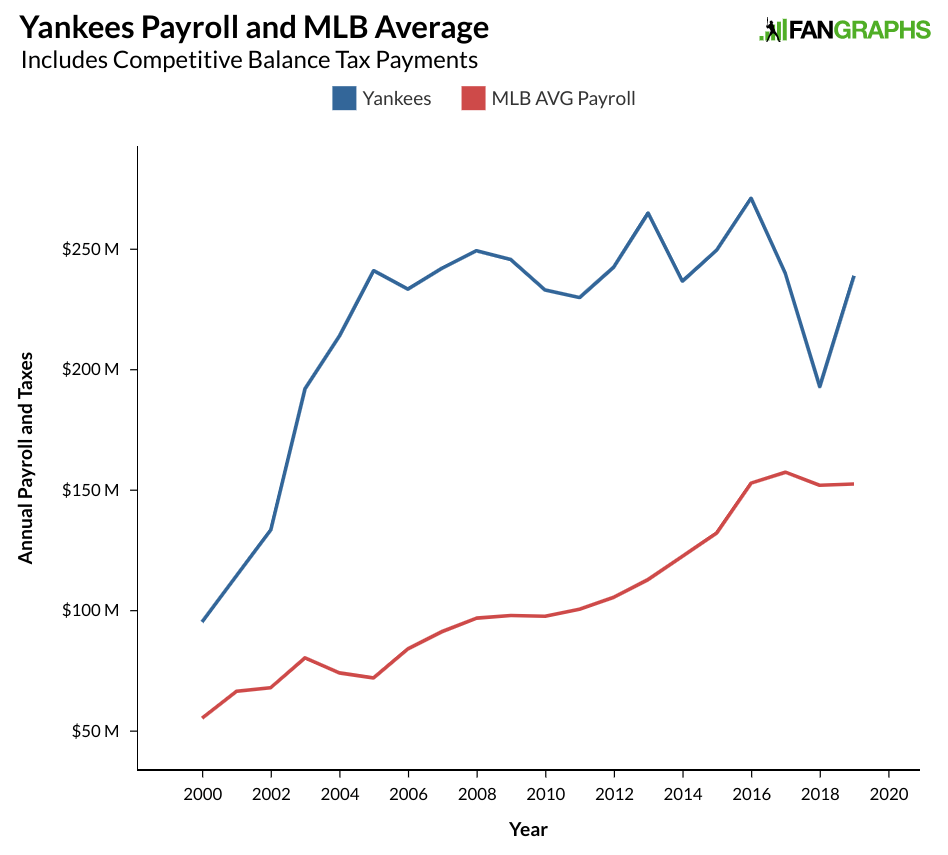

To try and add to that perspective, here’s how much the Yankees have spent on payroll and the taxes that come with it over the last 20 years compared with league-average payrolls.

The Yankees sat below $100 million in payroll back in 2000 when Derek Jeter, Mariano Rivera, Andy Pettitte, and Jorge Posada cost a combined $25 million. As those players got older and more expensive and the Yankees added Roger Clemens, Mike Mussina, Jason Giambi, Alex Rodriguez, and retained Bernie Williams, the team’s payroll grew. In 2003, it jumped up close to $200 million coinciding with a new Collective Bargaining Agreement. Jumps in 2004 and 2005 saw the Yankees up to around $240 million, roughly three times the average MLB payroll. Then the team just didn’t move for more than a decade. From 2000-2009, Yankees payroll averaged right around $200 million while the rest of baseball averaged about $80 million. Over the next decade, MLB payrolls moved up $50 million on average while the Yankees didn’t keep pace on a percentage (or even dollar) basis, moving up around $40 million.

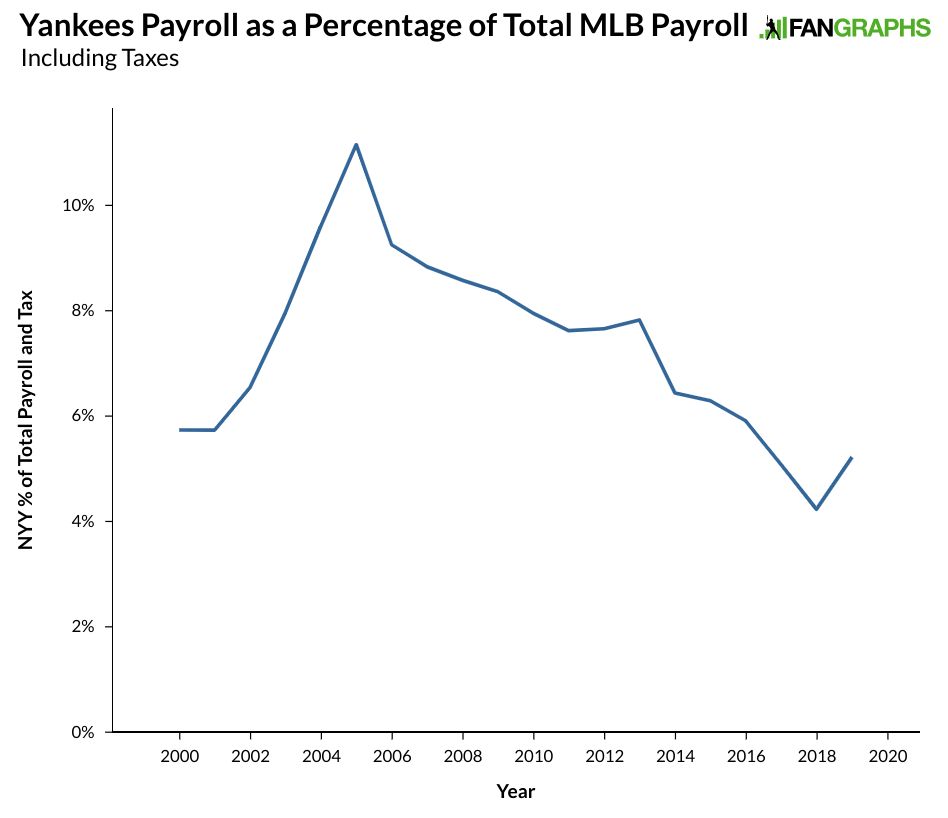

There’s an argument to be made that the Yankees’ massive jump in the early 2000s outstripped what might have been reasonable compared to their revenues and financial status, and that staying at around $240 million reflected a necessary correction. Here’s where the Yankees payroll has been as a percentage of total MLB payrolls since 2000.

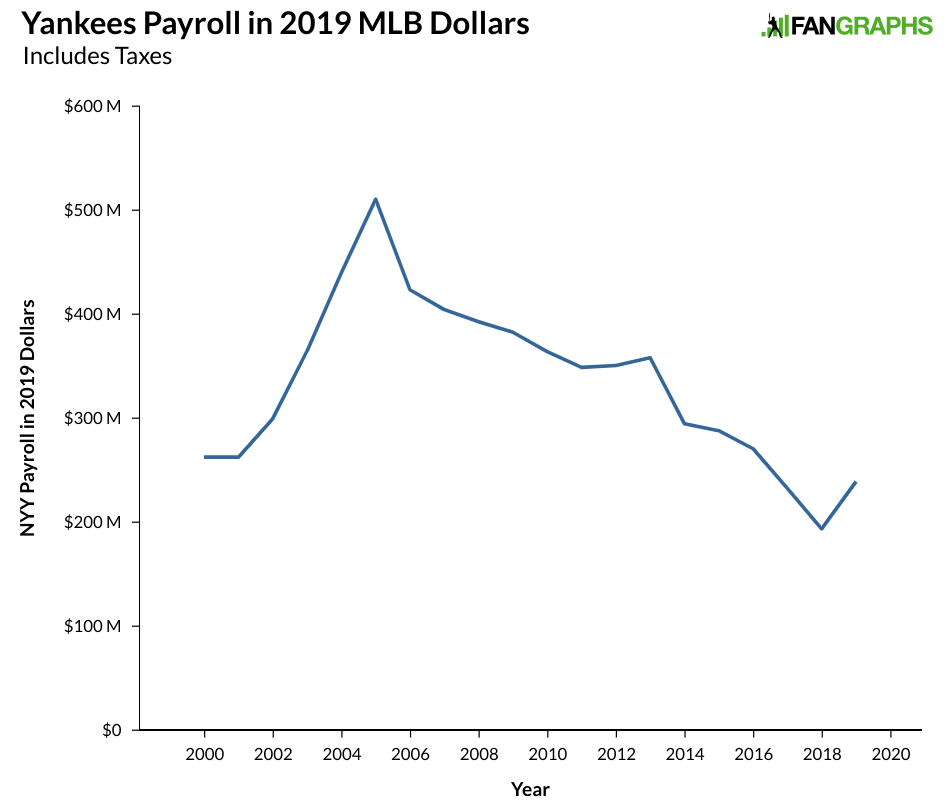

When the Yankees took their big jumps in payroll, they alone represented about one-eighth of spending in the game. As that spending stagnated in New York and rose elsewhere, the percentage dropped. While MLB payroll has gone unchanged the last few years — which the Yankees may hold significant responsibility for in 2018 — the team’s rise in payroll this past season has moved them up a bit, though they are still below 2000 and 2001 levels. Because percentages can be a bit opaque, I took those percentages and put them all in 2019 payroll figures to help show what the Yankees would be spending this past season if they were still occupying the same percentage of payroll as they’ve done in the past.

We can look at the expenditures from 2004 through 2009 and think maybe those payrolls weren’t, in 2019 buzzword terms, sustainable. The team needed to go up from their 2000 spending level because having Pettitte, Jeter, Rivera, and Posada all on bargain contracts isn’t something to be relied upon, especially if they wanted to win more than 87 games like that 2000 squad. Even under that reasonable assumption, going up 10% from 2000 and 2001 levels instead of 80% would still put payroll close to $290 million in 2019 dollars.

I’m not saying there is a correct number the Yankees should spending. But I think it is fair to point out that the team has been spending at much lower levels than they have in the recent past, that revenue sharing has gone down for the Yankees, that Forbes estimates the club has $156 million in profits over the last decade, and that they had enough money to buy back into a majority share of the YES Network (whose profits are shielded from revenue sharing). It’s also fair to note that the franchise’s sharp downturn coincided with their first pennant-less decade in 100 years, when they started the 1910s as the New York Highlanders. It might also be reasonable to note that the team made it to the ALCS with only two-and-a-half starting pitchers, and that in their first three losses of that series, their starting pitchers averaged under four innings per start, and that in a win-or-go-home contest, the team went with a bullpen game.

The Yankees haven’t been saving money over the last decade. Individuals and families save money; MLB franchises increase profits. The Yankees have spent this time increasing profits and looking for a way to win like they used to without spending like it. The past two seasons have proved successful in that regard. The resulting profits also serve to decrease the club’s chances of winning a World Series. It’s a choice the Yankees have made that differs considerably from the previous decade. The Yankees are trying hard to achieve massive profits and winning baseball, and those two goals often compete against each other. They did so last offseason and at the trade deadline, and it will happen again this winter. We will see what choice they make.

Craig Edwards can be found on twitter @craigjedwards.

I’d also like to see the Yankees’ payroll+tax against revenue plotted against the MLB average payroll+tax against revenue.

Because, as far as I can tell, it’s currently less than that of the Rays (and nowhere near as high as that of the Red Sox).

The facile line from desperate upvote-hounds is to cite the Yankees’ payroll as a way mock those who call Hal “cheap”…but that doesn’t actually account for how much freaking money the Yankees take in every year.

In 2018, the Yankees spent the smallest % of revenue on payroll of any team in the league: https://www.pinstripealley.com/2019/4/16/18305860/yankees-2018-spending-payroll-percentage-revenue-lowest-mlb-priorities-winning-steinbrenner.

Their 2019 payroll was higher than in 2018, but even if we hold revenue constant from year to year, their 2019 payroll was still just 33% of their revenue, which would have been the second lowest rate in 2018. Adding in their luxury tax takes them all the way up to 35% or so, tying them with the Dodgers for the third lowest rate in the league.

To put their revenue in context, if the Yankees spent a league-average % of their revenue on players, they’d have a $300 million payroll. And if they spent as much as the Nationals did, they’d have a $400 million payroll.

How much income a person or entity has doesn’t determine their thriftiness. Take the average cost for a Honda Civic is 20k. If Bill Gates pays 40k for one opposed to 3B is he cheap? Certainly 60k is a fraction of a percentage of his 106B net worth. Essentially that is the argument you are making here.

You’re not looking at this properly. When someone buys a car, they aren’t competing against 29 other car owners for the best car. It is completely fair to compare revenue/payroll in a competitive endeavor which is based, in no small part, on the ability of one side to buy better talent than the competition. That the Yankees have chosen to retain far more income than their competition, while at the same time, have been far less competitive on the free agent front is a simple fact.

They would be less competitive on the market if they spent less money, they still rank top 3 in total payroll year to year. The fact that their revenue goes up based on the ambiguous information we have and not accounting for expenses and investor payouts, doesn’t change the force of nature the Yankees are on the free agent market. They spent more last off season than the whole entire Marlins payroll for crying out loud.

“How much income a person or entity has doesn’t determine their thriftiness.”

… Yes, it categorically does. Read any “thrift expert” who provides budgeting advice and you will see that they use percentages, not raw numbers. The standard advice is to spend about 30% of your gross income on housing, for example, not that everyone should just spend $25,000 (or whatever) on rent.

The argument you’re making seems to be that thriftiness is measured by whether one pays market price for something. That is, Bill Gates could easily afford to spend $60,000 on a car, but a Civic only costs $20,000, so it wouldn’t be thrifty for Gates to spend $60k on a Civic. In reality, of course Gates wouldn’t spend $60k on a Civic, because *that’s not what Civics cost*.

The real point is that it would be perfectly reasonable for Gates to spend $100,000 on a new car, because that’s an infinitesimal fraction of his income, whereas $100,000 would be a truly insane amount for me to spend on a car. And literally the entire reason for that difference is that Bill Gates has much, much, much more money than I do. The question isn’t “Is that a fair price for that car,” the question is “Is that price something this person can afford?” And the answer absolutely depends on the person’s income.