Timing Isn’t Everything, But It’s Certainly Something

Hitting a baseball is an unthinkable accomplishment of timing. In order to strike a ball traveling from the pitcher’s hand to the plate in less than half a second with a slab of wood, a hitter must execute an elaborate sequence of movements on time. When do you lift your front foot? When do you load your hands? When do you fire your hips? It’s a sophisticated choreography; a beat late at any point can doom the swing.

Picture Fernando Tatis Jr. When Tatis is at the plate, he shifts around like a predator stalking its prey, eyes peeled for the exact moment when the pitcher lifts his front foot so that he, too, can get his toe down at the right time, and then his hands up, and then finally the barrel through the zone:

If hitting is such a delicate sequence, conditional on the pitcher’s own timing, it follows that pitchers who mess with that timing can improve their performance; by extension, pitchers who groove their deliveries will underperform their stuff. In an interview with David Laurila in 2017, Jason Hammel described changing his delivery for these precise reasons.

“I’ve also changed my delivery a little bit, to hide the ball and be a little more deceptive,” Hammel told David. “I made that adjustment last year. In the past, I had a very timeable delivery, and for a hitter, timing is everything. If you can kind of rock with a pitcher as he is going through his delivery, you don’t have to guess, at certain points, when things are going to happen — it’s very predictable.”

What is a “timeable delivery”? What isn’t? I think two rookies can help demonstrate the concept described by Hammel here: Angels reliever Ryan Johnson and Tigers starting pitcher Jackson Jobe.

If you’re a reader of FanGraphs dot com, or the broader baseball internet, you’ve probably heard of Jobe. But my guess is only the real freaks are familiar with Johnson, a 2024 draftee who the Angels pushed straight to the big leagues this year before he had appeared in even a single minor league game.

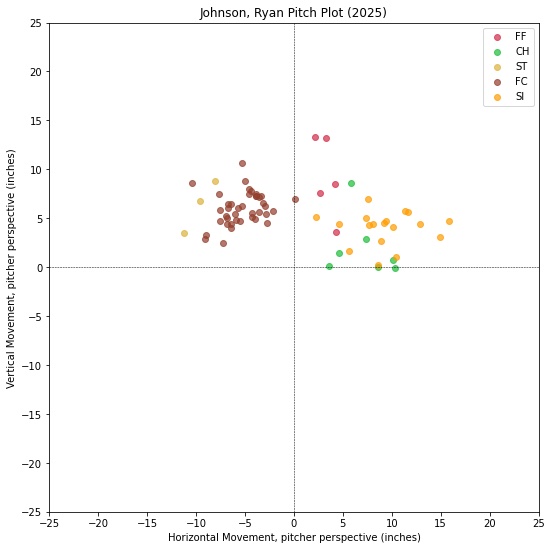

What makes this aggressive promotion schedule notable is that Johnson doesn’t have great stuff. He sits 94 on his sinker and throws only the occasional four-seamer. In general, getting swing and miss requires a spread of pitch movements. If everything moves in roughly the same window, a hitter won’t have much trouble covering the variety of potential pitch movement patterns. There aren’t many pitch plots in the majors with this degree of clustering. According to the new Baseball Prospectus arsenal metrics from Stephen Sutton-Brown, Johnson’s arsenal ranks in the sixth percentile for Movement Spread:

Johnson does feature one clear plus pitch, a “cutter” (actually more of a slider) that breaks five inches to the glove side with surprising lift at 90 mph. But Johnson’s viability as a major leaguer, I suspect, is largely a function of his peculiar release.

Out of the windup, Johnson starts pretty conventionally, repositioning his right foot on the rubber but otherwise maintaining a consistent rhythm. But at glove break, he engages turbo mode, rushing toward the plate with a minimal leg lift. It’s jazzy and funky, and it disrupts the batter’s delicate sequence of movements:

With runners on, Johnson opts for the straight turbo approach. In terms of time to the plate, it must be among the fastest in the league, giving batters little chance to “rock with the pitcher,” as Hammel put it:

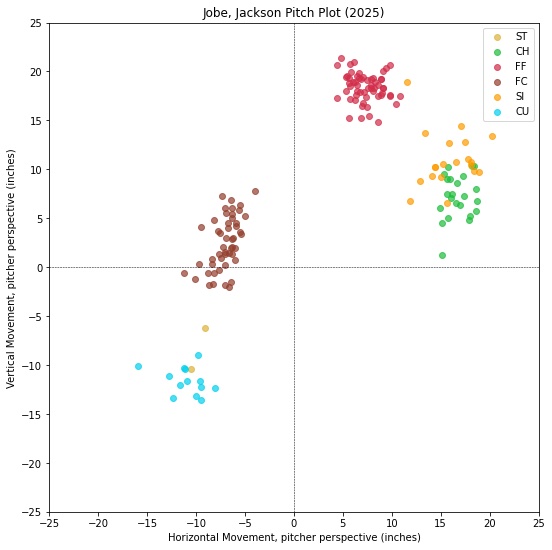

If the unorthodox nature of Johnson’s delivery helps his stuff play above the estimation of the models, the reverse may be true for Jobe. The models love Jobe, and it’s not hard to understand why. This is like someone created a pitch plot in a lab to maximize whiffs. Look at the beautiful separation between his pitches:

Jobe’s fastball averages 18 inches of induced vertical break at 96 mph. His “cutter” (also in truth a slider) breaks seven inches to his glove side at plus velocity. His hard curveball and depth-y changeup expand the vertical and lateral dimensions of his arsenal. Everything moves fast and breaks big, and hitters must account for all dimensions of the strike zone. Stuff+ gives him a 120 overall grade, above aces like Jacob deGrom and Cole Ragans; his PitchingBot stuff grade checks in at a 58 on the 20 – 80 scale. BP’s arsenal metrics put his Movement Spread and Velocity Spread at the absolute top of the scale, 99th percentile for the former metric and 97th percentile for the latter.

Frustratingly for pitching analysts, Jobe has not yet met his immense expectations. In Double-A last season, his 27.1% strikeout rate ranked around the 80th percentile — solid, but not necessarily reflective of a no-doubt strikeout beast.

The whiffs have been even scarcer during his (very brief) time in the big leagues. Jobe’s first two starts in the majors could not have come in more favorable conditions. The first came against the Mariners on a cold night in Seattle, while the second was against the White Sox. His fastball was a particular issue — in that second start, Jobe threw 28 fastballs and got exactly zero whiffs.

His third start, which came this past Saturday, was his best; he fired six scoreless innings against a slumping Twins offense. But even in that start, Minnesota had no trouble making contact and avoiding chase. Jobe struck out just two hitters and notched a single whiff on his 27 heaters. For the first time, his cutter usage matched his four-seam usage, suggesting that Jobe realizes he needs a deep mix to pitch around these limitations. His 15% strikeout rate through three starts is uncomfortably close to that of Jack Kochanowicz, whose lack of strikeout ability merited an entire article.

It’s very early in Jobe’s career; all of this could flip in the span of a single start. (Shota Imanaga and Tanner Bibee, for example, are also posting low strikeout rates in the early part of the season.) It’s also possible the entire explanation here is that Jobe isn’t putting pitches in competitive locations. But I’m guessing the lack of agreement between the stuff models and the actual performance of Jobe’s stuff relates to the way he delivers the baseball. In Eric Longenhagen’s recent Top 100 Prospects update, he quoted Lance Brozdowski, who wrote that Jobe might settle in below projections because “Jobe’s delivery is easy for hitters to time.”

Lance elaborated on this idea in subsequent posts on Bluesky. Jobe’s release, he wrote, is “generic.” His release height is around league average; his extension down the mound is unremarkable. All that, Lance guessed, means that “his ball is coming out of a point in space that hitters see frequently.”

I’ll add a little to this idea. I think there’s something about the rhythm of Jobe’s delivery — in direct contrast to the jittery nature of Johnson’s — that allows hitters to more easily time his pitches. As Hammel put it, you can rock with Jobe as he moves through his delivery. To my eye, Jobe moves toward the plate in a smooth, deliberate manner. There’s nothing here that I can see that messes with the expectation of the hitter:

As far as I can tell, Jobe also doesn’t do much to alter his delivery from pitch to pitch. Jesús Luzardo, for example, slipped in a mid-delivery slide step at times against his recent start against the Braves, keeping hitters off-balance as he moved through the lineup. I’ve watched the majority of pitches thrown by Jobe this season and seen little evidence of this type of variability:

I concede that I could soon sound like a total dummy. Jobe’s raw talent surpasses nearly every pitcher on the planet, and it might all click as soon as he starts locating his fastball at the top of the zone. But thus far in his short professional career, there is clearly a mismatch between the theoretical talent and Jobe’s actual performance, and I think it might just have something to do with the nature of his delivery. Ryan Rowland-Smith, one of the Mariners’ color commentators, summed it up well in that first start of the season: “He could just be a guy [with] really good stuff [but] easy to pick up,” Rowland-Smith said.

Is there a way to quantify or operationalize the timeability of a delivery? It seems possible. Driveline Baseball created an Occlusion Score, which measures how long the pitcher hides the ball from the hitter. Another element to consider might be the time to plate for each pitcher, which I’ve been told is relatively easy to measure using tools like Dylan Drummey and Carlos Marcano’s BaseballCV models. But these considerations are currently missing from even the most cutting-edge public models. The variation between pitchers is pretty small, I’d guess, meaning that it will only make a marginal difference in most cases. But there are always outliers, and I suspect that Johnson and Jobe illustrate this better than most.

Michael Rosen is a transportation researcher and the author of pitchplots.substack.com. He can be found on Twitter at @bymichaelrosen.

It has been jarring to see Jobe struggle to put hitters away, because the pitches themselves look really nasty, even on TV. Funny enough, he reminds me of teammate Casey Mize, a guy with supposedly hellacious stuff but that couldn’t miss pro bats. As a Tigers fan, I’m hoping Mize’s recent improvements will osmosis their way over to Jobe.

True, but Jobe has even better stuff than Mize. The fastball-splitter combo can work well, but can also take a while to master (see Kevin Gausman).

I agree with this, which is why I think Jobe will eventually figure it out through tinkering (he’s already shown he can add/modify pitches to his arsenal).

That seems to happen to a lot of young guys. Dylan Cease got 10 K/9 in his initial callup in 2019, but in 2020 (his first “full” year) that dipped to 6.8. Since then he’s been getting a lot of whiffs. I think it probably ahs something to do with “learning how to pitch” instead of just being a thrower. Big league hitters are just a lot smarter than AAA hitters and learning how to get them to swing and miss takes a lot of guys a little time.

Cease also had command issues early, and I think MLB hitters are really good at taking advantage no matter the stuff.

Hunter Greene. Nathan Eovaldi (took him several years). Jobe is still pretty young and like others have said he still needs to get better at pitch command.

Is it an organizational thing? Manning has had the same issues. Of course, Skubal doesn’t have any issue with this

Manning keeps getting hurt.

I love Jobe’s stuff like everybody in the world but there were yellow flags all over his profile. Guys who throw that hard with that much spin who aren’t striking out everyone in AA and AAA make me wonder about their ceiling.

Shane McClanahan struck out everyone. Dylan Cease struck out everyone. Tarik Skubal struck out everyone. Spencer Strider struck out everyone. Jackson Jobe…was fine.

I don’t know what the future holds for him, he’s still quite young, and he has lost a lot of time due to injury (which, depending on how you look at it, is either a harbinger of future problems or a reason to project on his development). But if I were to draw up a list of pitchers who were prospect eligible this year with a good chance to be a 4+ win pitcher, I don’t think his name would be on it.