Will Harris Played Well, Didn’t Get Rewarded

When Will Harris entered Game 7 of the World Series, the Astros were in the driver’s seat. There was only one out in the seventh, and Houston was up by a lone run, but teams in that position usually win — per our Win Expectancy chart, that situation ends in victory 68.7% of the time.

68.7% is notably not 100%, however. When Harris threw Howie Kendrick an 0-1 cutter, Kendrick demonstrated why:

The game wasn’t over after that home run, but it proved decisive nonetheless. The Nationals never relinquished the lead, tacking on insurance runs in the eighth and ninth, and sharked their way to a World Series title. Harris gave up a single to Asdrúbal Cabrera before Roberto Osuna replaced him; after the game, he became a free agent, and may never pitch for the Astros again.

The Kendrick home run was the most important single play of the World Series, and so it’s natural that A.J. Hinch’s decision to use Harris has been the focus of much of the post hoc analysis of the inning. Gerrit Cole was in the dugout warming, and might have been available to face Kendrick. Worried about a starter entering mid-inning? Osuna was also ready — he came in later in the inning, after all.

But this analysis has a central thread that I dispute. At its core, it comes down to the fact that the Astros chose to go with Will Harris, and then he delivered a bad result. From there, you can determine whether Harris was a good ex-ante choice, whether Greinke could have stayed in, or any number of possible detours.

In framing it this way, it’s implied that Harris did a bad thing. Maybe he was the least likely person to give up that home run or maybe he wasn’t, but Hinch picked him and he caused the Astros to lose. To me, that’s simply untrue.

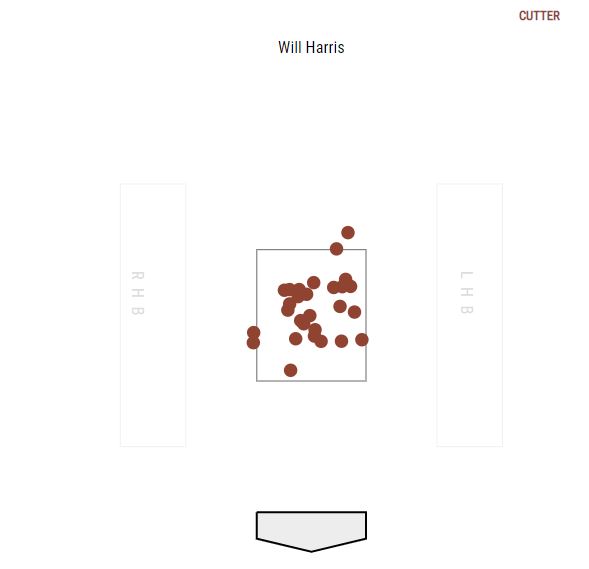

Take a look at the location of the pitch Kendrick hit:

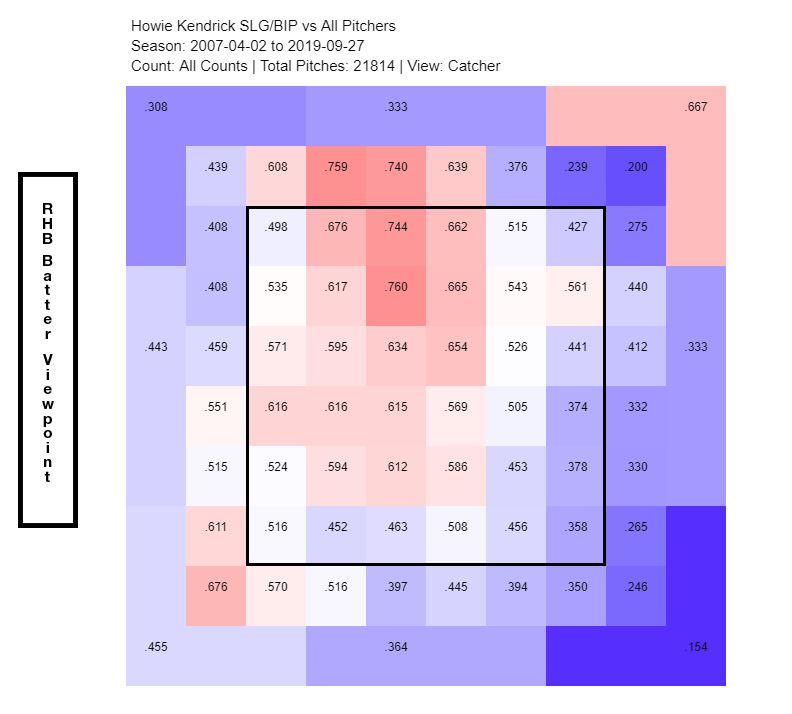

This wasn’t some middle-middle cupcake of a pitch; it was on the black, almost precisely on the lower outside corner. It wasn’t a flat fastball, either; it was Harris’s signature cutter, with glove-side break carrying it away from Kendrick’s bat. What’s more, it was located where Kendrick has historically had the least power:

This isn’t a loose use of the word “least,” either. Break the strike zone down into the 36 sections you see above, and Kendrick has the lowest slugging percentage on contact in the specific zone where Harris threw that pitch.

Moving the focus from Kendrick to Harris doesn’t make the pitch seem any worse. In his eight-year career (including the playoffs), Harris has thrown 114 cutters to more or less that location, the low outside corner. Batters have only swung 25 times, which makes sense — it’s a hard pitch to do much with, and it’s close enough to being off the plate that there’s a pretty good chance of having it called a ball.

Those 25 swings make for a small sample, but until this pitch, the results have generally favored Harris. Of the 25, seven were swinging strikes and six went foul. Another eight turned into outs; five grounders, two line drives, and a fly ball. Three became groundball singles. The 25th changed the outcome of the World Series.

Nor is this a case of a ton of hard contact that simply hadn’t caught up to Harris. The hardest-hit ball, inclusive of Kendrick’s home run, was a grounder with a 99.9 mph exit velocity from earlier this year. Kendrick’s home run was the second-furthest a player hit one of these low-corner cutters in Harris’s career, and it barely made it out of the shallowest part of the park. Put simply, Harris doesn’t allow home runs on low cutters. Take a look at the locations of every home run he had allowed against the pitch before Kendrick’s swing:

In fact, no one allows home runs on low cutters. Since 2008, between the regular season and the playoffs, there have been 1,741 cutters thrown by a righty to a righty in the rough location of Harris’ pitch that resulted in fair contact. Of those, a whopping two (not counting Harris’) went for home runs. If you’d prefer to include foul balls, the sample is even larger, but the results the same: batters have made contact with 3,160 low and away cutters, of which again two became home runs.

Of course, none of these cutters were the exact pitch Harris threw. There was only one of those, and it worked out as poorly as possible for Harris. It’s not fair to absolve him of blame completely. He could have thrown a different pitch; Kendrick had whiffed on a first-pitch curveball. He could have thrown it with slightly more mustard; maybe 92 on the black gets the job done where 91 isn’t enough.

But for the most part, blaming Harris misses the point. It’s easy to look at the way the series ended and moralize. Howie Kendrick is the hero, Will Harris is the goat, and A.J. Hinch is the surrogate goat. Those are all true based on the outcomes, but they miss a central element of what happened. Process matters, and Harris didn’t lose because of a bad process or a lack of execution; he lost despite doing exactly what he hoped to do.

Baseball is zero sum, but that doesn’t mean every failure is built the same. Will Harris is going to remember this play for the rest of his life. But if you ask him what he’d do differently, and if he’s honest, I think he’d say nothing. That was a great pitch. Kendrick was just better.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Absolutely agree. Thanks for the supporting information.