Xander Bogaerts is Selectively Aggressive

When Xander Bogaerts played in the 2013 World Series as a 20-year-old rookie, it was easy to see the start of a promising career: he was a glove-first shortstop (though he played mainly third base in 2013, ceding short to Stephen Drew) with enough pop and size to eventually be an impact bat. Over the next four years of his career, though, that promise of power remained tantalizingly out of reach. At the end of 2017, Bogaerts’ career line was nearly exactly average (101 wRC+), but the extra-base hits never quite developed as projected. His .127 ISO was in the 19th percentile of batters with at least 2000 PA over that time period, and his slugging was hardly better (.409, 28th percentile).

Now, a league average bat at shortstop is still tremendously valuable. Bogaerts was worth 12.9 WAR over those four-plus years, a 3 WAR/600 PA pace that would make him a starter on virtually every team. Still, you could look at the promise of a 20-year-old Bogaerts, a 6-foot-1 live wire getting important at-bats on the biggest stage, and wonder why he hadn’t tapped into more offense. It had been four years, after all. Surely if he was going to fill out and add power, it would have already happened.

Two years later, that 2017 endpoint looks awfully conveniently timed to fit a narrative. Since the start of the 2018 season, Bogaerts has found another gear. He’s batting a scintillating .291/.366/.526, good for a 134 wRC+, and the power has miraculously appeared, with his .235 ISO ranking in the 84th percentile among qualifying batters. Still only 26, Bogaerts now looks like one of the best players in the game, full stop. The player fans and scouts saw glimpses of in 2013 is finally here.

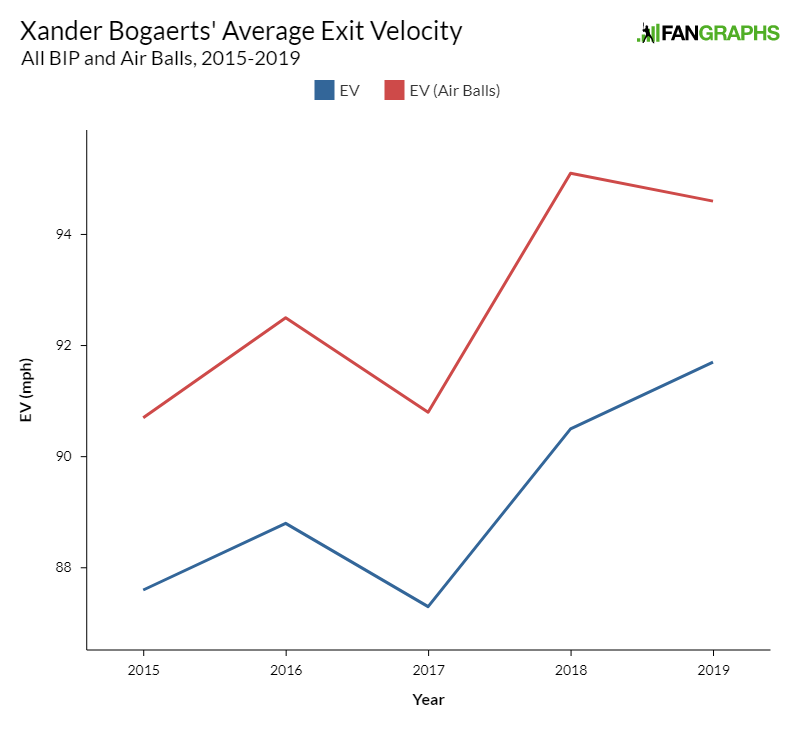

What did Bogaerts do to tap into his enormous potential? Well, given that his power numbers have spiked across the board while his strikeout and walk numbers have barely budged (18.5% strikeouts and 7.2% walks 2013-2017 versus 18.1% and 10.2% thereafter), it would be easy to say he just started hitting the ball harder. He always looked like he had the potential to do that. A few pounds of muscle here, a little physical maturation there, a smattering of juiced baseball, and warning track power becomes home run trots. Take a look at Bogaerts’ average exit velocity from 2015 (the first year of Statcast data) to now, on all batted balls and also balls he hit in the air:

These averages tell the exact story we’re looking for with Bogaerts. There’s only one problem: averages lie. Consider the case of two players with average exit velocities of 90 mph. One of them hits every ball 90 mph. The other hits 110 mph rockets half of the time and 70 mph bleeders the other half. It would be inaccurate to say that they hit the ball equally hard, but that’s exactly what looking at average exit velocity would lead us to conclude.

The results aren’t equal, either. Balls hit between 89 and 91 mph this year have produced a .268 wOBA. The 109-111 mph range produces a 1.038 wOBA, while 69-71 mph check in at .287. Thus, our all-90s batter produces a .268 wOBA on contact (basically Austin Romine’s contact quality) while the boom-bust player clocks in at a staggering .663 (Joey Gallo-ish). Clearly, average exit velocity isn’t the metric we need to tell Bogaerts’ story.

Let’s look for power in a slightly different way. If Bogaerts really added power, we would see it in the balls he hits the hardest. That’s basically inarguable; if one season you can hit the ball 100 mph and the next you can hit it 110 mph, you’re more powerful. Here’s the tale of the tape from 2015-present for all line drives and fly balls, the swings where exit velocity produces extra bases:

| Year | Max Exit Velocity (mph) |

|---|---|

| 2015 | 110.6 |

| 2016 | 111.8 |

| 2017 | 111.3 |

| 2018 | 111.9 |

| 2019 | 111.7 |

And just to be thorough, here’s the average of the five hardest balls he’s hit each year, just to keep a single spike in one year from messing with the data:

| Year | Top 5 EV (mph) |

|---|---|

| 2015 | 109.3 |

| 2016 | 111.0 |

| 2017 | 110.1 |

| 2018 | 110.9 |

| 2019 | 109.9 |

That’s all the evidence I need to say that Bogaerts isn’t getting more powerful. In a nutshell, this is the difference between the raw and game power that Kiley and Eric talk about in prospects. Bogaerts has the same strength he’s always had. He’s converting it into usable outcomes at a better rate over the last two years, though, and that’s what shows up in his stats.

Let’s look at it in a slightly different way, this time using Baseball Savant definitions. The advent of Statcast data allows for a statistic called Barrels, essentially batted balls hit at speeds and angles that make them likely to go for extra bases. This tracks pretty well with visual observation; if you see a ball off the bat and think double or home run, it’s probably a barrel. Take a look at the percentage of batted balls that Bogaerts has barreled up each year since 2015:

| Year | Barrels/BIP |

|---|---|

| 2015 | 2.51% |

| 2016 | 5.26% |

| 2017 | 1.31% |

| 2018 | 9.83% |

| 2019 | 11.30% |

We’ve found the source of Bogaerts’ increased power, but not what allowed him to tap into it. After all, every player would follow the advice of “just make excellent contact more often” if they could. We need to find something that’s changed that’s letting Bogaerts square the ball up nine times more often in 2019 than he did in 2017. The answer isn’t that surprising, honestly. You’ve probably already guessed it. Bogaerts is getting more power because he’s swinging at the ball in locations where he can do more damage.

Conveniently enough, Bogaerts hasn’t radically overhauled his swing since reaching the majors, though he’s tinkered with timing mechanisms and stances slightly. That means we can look at his career results on balls in play to get an idea of where he gets his power from. Take a gander at Bogaerts’ career slugging percentage on balls in play at various points in the strike zone:

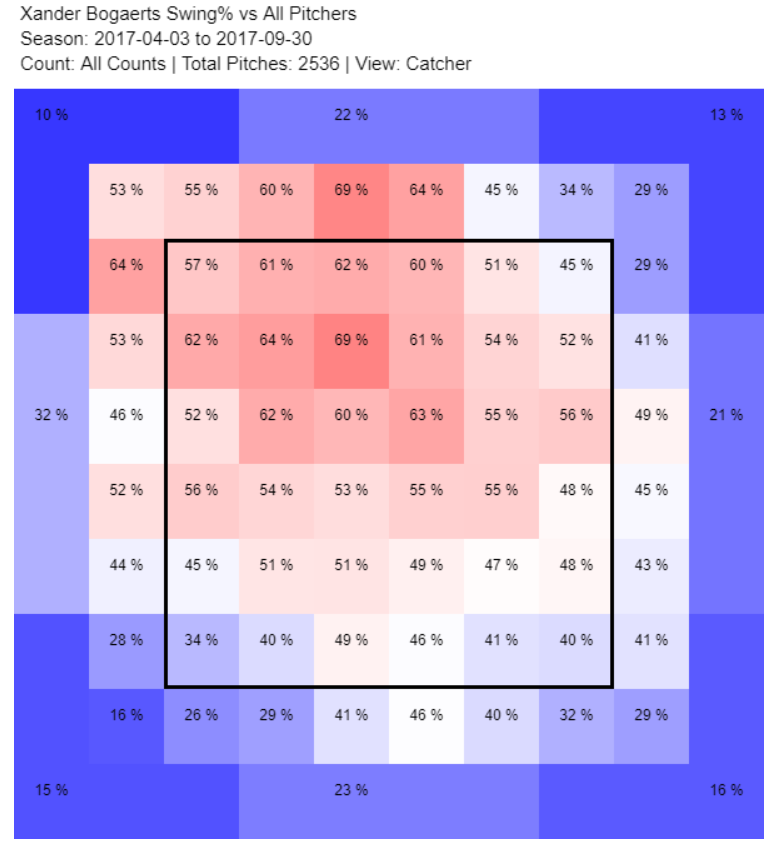

Yeah, there are some weird sample-size issues with pitches extremely far out of the strike zone, but for the most part, there’s a consistent story. Bogaerts has always generated power from the inner third (and, of course, middle) of the strike zone. Take a look at where he swung in 2017, the last year of his power outage:

This doesn’t really look like the distribution of swing rates you’d like from someone who has no power on pitches away. Bogaerts has always run high contact rates, which means those swings at pitches away resulted in low-value balls in play. Middling natural power and a lot of swings outside your power zone produces below-average contact quality, and that was largely what happened to Bogaerts in 2017.

Now that you’ve seen the old Xander Bogaerts, take a look at what he’s done since then. Here are his swing rates by zone since the beginning of 2018, when his power went from 0 to 100 real quick:

There are 24 zones in the inner two-thirds of the strike zone in these graphics. Bogaerts’ swing rate went up in 21 of those zones. That’s choosing pitches to maximize your power. If you think that this is just an artifact of swinging more often, think again. There are 48 other zones on this heatmap. Bogaerts’ swing rate went up in just 22 of them, less than half. In other words, he’s getting the best of both worlds: selective aggression where he can put a charge into baseballs, and discretion where he can’t.

There’s just one mystery left to solve. If Bogaerts’ plate discipline has improved so much, if he’s figured out how to swing more at strikes without swinging more at balls, shouldn’t we see it in his strikeout and walk numbers? Well, yes and no. Swinging at more strikes isn’t necessarily going to decrease strikeouts, because as I mentioned above, he’s always made a ton of contact. Bogaerts has been above average in contact and zone contact every year starting in 2015 (the first year he struck out less than the major league average). Swinging at more and different strikes might result in Bogaerts putting different balls into play, but pitchers weren’t throwing pitches in the zone past him for a strikeout very often anyway.

What about the second part of the equation, more walks? Well, swinging at better pitches without swinging at more bad pitches doesn’t necessarily produce more walks. The easiest way to walk more often is for pitchers to throw you fewer strikes, and Bogaerts is starting to get a power hitter’s treatment from pitchers. From 2013 to 2017, he saw pitches in the strike zone 46% of the time, significantly higher than league average, as pitchers dared him to beat them. Now that he’s unlocked his natural power, that number has declined to 42.4% over the last two years, pretty much average. He’s walking 10.2% of the time since 2018, up from 7.2% before then, and that number will likely continue to climb if pitchers start to avoid him more.

Xander Bogaerts’ subtle breakout is a lesson in the nuanced ways baseball players can change and improve. You don’t need to get stronger, change your swing to put the ball in the air, or start swinging from your heels to boost your power. You don’t need to be a totally different player. Sometimes, doing something as basic as trying to focus more on the part of the strike zone where you’re good at hitting is all you need to do. Sometimes the batted balls you’re looking for were always there, just covered by the noise of the batted balls you didn’t want. Not every change for the better remakes a player. Some just shuffle the existing parts and land on a better configuration.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

I also wrote about this and found “On breaking balls, he is swinging at a career low 33.6% of pitches. While on off-speed pitches, he is swinging at 36.6% of pitches seen. With pitches in the zone, Xander is swinging at similar rate to 2017, meaning the difference must be in pitches that he is chasing outside the zone. For pitches outside the zone, Bogaerts is chasing a career low 20.2% of breaking balls and 18.3% of off-speed pitches compared to the 23.8% and the 26.3% in 2018”

“Bogaerts has been crushing off-speed pitching in 2019 with a .765 SLG and a .442 wOBA. He has been laying off changeups down in the zone and hitting them for homers when they are left up. In 13 batted ball events, Bogaerts has hit 3 for home runs, 5 for fly ball out, 3 ground ball outs, and a pop-up. His launch angle on off-speed pitches in a career high 21 degrees while his GB% is a career low 23.1%.. His gain in barrels is nearly all from off-speed pitches increasing from less than 5% to 23.1%. ”

Also, Boegarts can’t hit curveballs.