Yadiel Hernandez, Sleeping Giant

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before. Why is it so easy to fill in the pool that the Washington Nationals own? That’s right — it has no depth. The Nats have relied on a stars-and-scrubs approach for years, hoping that their stellar headliners can offset some of the clunkers at the bottom of the roster. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t, but the central motivation behind their roster has been strikingly consistent in recent years.

In 2021, some of the stars aren’t shining as brightly as the team hoped. Juan Soto has missed three weeks with injury and is off to a slow, power-sapped start. Stephen Strasburg made only two starts before landing on the Injured List. Patrick Corbin has been disastrous. Offseason acquisitions Josh Bell and Kyle Schwarber, who were supposed to stabilize the lineup, are off to slow starts, Bell in particular. It’s not a great year for the boom/bust roster-building philosophy.

In a great stroke of irony, however, the Nats have found a solid bat that could lengthen their lineup and give Soto and Trea Turner some help. There are just two problems: they have nowhere to play him, and he still has some tinkering to do. Yadiel Hernandez looks like the kind of hitter that good teams need, an above-average bat summoned from the minors. Due to the team’s roster construction, he’s been banished to the bench. Should a spot open up, however, he might be the exact thing the team has been missing.

Some quick backstory before I delve into why Hernandez has piqued my interest. He defected from Cuba at age 28 in 2015, then signed with the Nationals the following year for a $200,000 bonus. He hit and hit and hit in the minors, ascending the ranks against younger competition, until he put up a .323/.406/.604 line in Triple-A Fresno in 2019. He made his major league debut — at 32! — last year, then made the team as its fourth outfielder this year.

On its own, that would be a cool story — a late-career veteran making good. But that’s not all. Hernandez rakes. He’s been grounder-happy in his brief big league showing so far, but I think there’s sneaky potential there, and here’s the thing: he’s already producing an above-average line. Any more improvement, and the team might have to start finding him a spot in the lineup, lineup juggling notwithstanding.

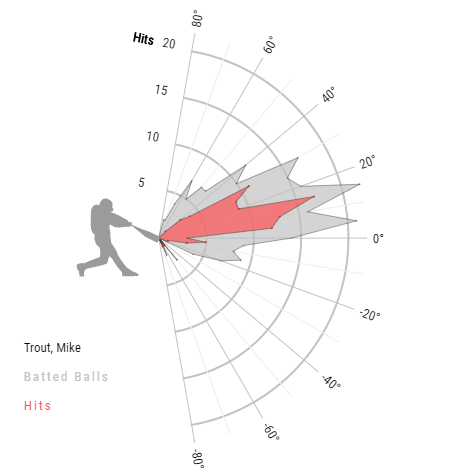

If you want to see what an ideal launch angle profile looks like, take a gander at Mike Trout over the past two years of play:

It’s glorious; the great majority of his batted balls are exactly where you want them as a hitter. It’s hardly surprising — best player in baseball and all that — but it’s good to see a visual representation of Trout’s penchant for crushing baseballs.

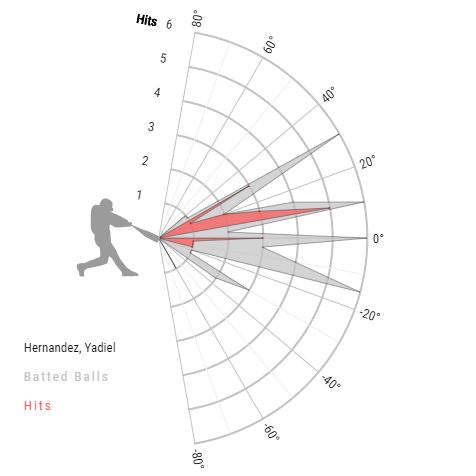

Hernandez doesn’t have nearly as pretty of a graph:

Those spiky bits partially reflect a lack of data, but they also reflect a ton of balls hit directly into the ground. Zero degrees, negative 15 degrees, negative 25 degrees; those aren’t going on his highlight reel anytime soon. Why are we looking at him again?

Those grounders are a problem, no doubt. But they’re obscuring something interesting about Hernandez. There’s one more spike in the launch angle chart, at 10 degrees. That’s a low line drive, the kind that routinely turns into singles and doubles, and Hernandez gets to them with such regularity that I’m willing to believe he can turn that skill into an above-average batting line consistently.

Most hitters are like lesser versions of Trout. They make their hardest contact in the air, and they make their hardest air contact to the pull side. That’s just how swings work: hitting instructors train getting the bat through the zone because bat speed increases the further into the swing you go. Later in your swing means both a higher chance of pulling the ball and higher exit velocities on average; physics explains why pulling the ball is so valuable.

Yadiel Hernandez hardly ever pulls the ball when he hits it in the air, which sounds like a bad thing. He’s hit 25 balls in the air in his brief major league career, and pulled only four of them. That sounds like the opposite of what you’d like to do.

There’s just one complicating factor: Hernandez has been tattooing the ball when he hits it the other way. With the caveat that these are hilariously small samples, here’s a leaderboard of average exit velocity on opposite-field balls in the air since Hernandez’s debut in 2020:

| Player | EV (mph) |

|---|---|

| Yadiel Hernandez | 96.1 |

| Adolis García | 95.3 |

| Jorge Alfaro | 94.8 |

| Buster Posey | 94.6 |

| Fernando Tatis Jr. | 94.4 |

| Juan Soto | 94.2 |

| Giancarlo Stanton | 94.1 |

| Christian Yelich | 94.0 |

| Justin Williams | 93.9 |

| Jake Cave | 93.8 |

Even outside the top 10, this list is studded with sluggers. That makes sense — if you hit the ball phenomenally hard, even your less-powerful opposite-field hits are still smoked. Hernandez — well, he’s 5-foot-9 and hasn’t hit a ball harder than 106.2 mph thus far in the major leagues. He’s on this list because he makes tremendous contact, not because he’s so big and strong that he’s bound to crush it once in a while.

Average exit velocity isn’t a great descriptive metric, because production isn’t a linear function of exit velocity. In simpler terms, if you hit one ball 70 mph and one ball 110 mph, you’ll do better than if you hit two balls 90 mph each, despite the same average exit velocity. By itself, this leaderboard doesn’t prove anything.

No matter how you slice it, though, Hernandez’s opposite-field power is legitimate. He’s first in baseball in the percentage of opposite-field balls in the air hit at 95 mph or harder, the cutoff that Statcast uses to determine whether a ball is hit hard. He’s eighth when it comes to the percentage he hits 100 mph or harder, true big-bopper territory, despite his modest maximum exit velocity. The top five of that list — Stanton, Eloy Jiménez, Tatis, Yelich, and Soto — makes it pretty clear that this statistic is capturing something meaningful about power.

With such wondrous pop to the weak side of the field, Hernandez must jump off the page to the pull side, right? Well, no — he basically never pulls the ball in the air. He’s been productive when he gets to the pull side, no doubt. 75% of his pulled air balls have been over 100 mph, a gargantuan number. That 75% is three out of four, however, and four batted balls does not a robust sample make.

Watch Hernandez swing, and you can see why. Here he is with two strikes, punching one:

Sure, you might say. That’s a good, solid two-strike swing. With no stride and a short stroke, he can defend the plate better, but he’ll naturally hit more balls to the opposite field. Here he is in a hitter’s count:

Huh. Slightly more leg kick, but the swing looks mostly the same. That’s just how Hernandez swings — a slashing swing that generates power to the opposite field. I’m not a hitting coach, and I certainly can’t say what Hernandez is trying to do up there, but it looks to me like he’s letting the ball travel deep into the zone, which naturally results in opposite-field contact.

To some extent, Hernandez’s swing is an innate trait at this point in his career. The high groundball rates, the smashed opposite-field line drives; they’re all part and parcel of his particular swing path. They’ve been working, too; though he’s consistently hit a ton of grounders, he’s compiled decent power numbers in the minors because the line drives and fly balls he does hit are scorched.

That would make him a fine role player, and that might be where it ends, but players sometimes change their stripes, changing grounders for fly balls or pulling the ball more often. The pure bat-to-ball skills he’s demonstrated — he’s 5-foot-9 and hitting balls right on the screws at a gargantuan rate — mean that if he starts to pull and lift the ball more, the results could be exhilarating.

Most of the time, players with this general profile don’t turn into sluggers, but that doesn’t mean all the time. The Nationals, in particular, have experience with it; Daniel Murphy dropped 10 percentage points of groundball rate, upped his pull rate, and took flight in D.C. Hernandez isn’t Murphy, but the precedent exists: bat-to-ball standouts can develop power seemingly out of nowhere. Murphy’s former teammate Justin Turner fits the bill as well, though he’s been a lift-and-pull guy so long it’s hard to remember his slap-hitting days.

Is Yadiel Hernandez another Murphy or Turner? Probably not! He’s 33 and still a rookie, which doesn’t give him much time to tinker with his approach at the expense of performance. What he’s doing now is good enough for a fourth outfielder, and that’s his job — why change? But if he starts setting the world on fire, don’t be surprised. He has the tools to blister the ball to all fields — it’s just a matter of whether he’ll find a way to get to that power consistently.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

i see nats fans are back in cocky asshole mode after a whole “miserable” ten days or so of “crap on all the good things they have because they have no concept of actual baseball despair” mode

but they are heroes and that even more self-consciously over the top schtick is just sooooooooo funny and clever

That was so bitter I could almost taste it through my screen, and I give zero craps about the Nationals as a team.

I see Nats fans who have returned to a fake regime after 10 miserable days or roughly all the good they have because they don’t have the right concept of hopeless baseball fashion

But they are heroes and they are even more self-conscious next to someone so funny and smart

Were there even any comments when you posted this? What on earth are you even talking about? What happened 10 days ago? I understand exactly none of your post