Yankees and Giants Exchange Intriguing Players

It feels like only yesterday that the Yankees snatched Mike Tauchman from the Rockies for a pittance and unleashed him on the AL East. In 2019, Tauchman was electric; his .277/.361/.504 slash line buoyed the Yankees in a season where they desperately needed it. Injuries (and 100 PA in the minors) kept him from playing a full year, but even in only 296 plate appearances, he managed 2.6 WAR, sixth among Yankees batters.

That performance didn’t carry over into 2020. Despite the team’s intermittent injury problems, the Yankees used him as a fourth outfielder and defensive replacement. He didn’t hit a single home run, a concise summary of what went wrong: his power disappeared overnight. By the start of this year, he was barely playing and out of minor league options, which makes last night’s development unsurprising: the Yankees traded him to San Francisco in exchange for Wandy Peralta and a player to be named later, as Jack Curry first reported.

Tauchman had lost his spot in the Yankees’ outfield, and it’s not hard to see why. Aaron Judge and Aaron Hicks are playing everyday, which left one outfield spot for three outfielders: Tauchman, Clint Frazier, and Brett Gardner. Tauchman and Gardner fulfill similar roles, and the team was giving Gardner the majority of the playing time while carrying no backup shortstop. Frazier is the only outfielder with options, but he’s playing far more than Tauchman, which meant Tauchman was the odd man out — the team needed to trade him to avoid exposing him to waivers.

The Giants are the kings of reclamation projects, so they ripped the Yankees off, right? I’m honestly not sure. If you want to read more than you thought possible about Tauchman, Alex Chamberlain is a great source, and his definitive Tauchman hype post will give you the rough idea: he developed power out of nowhere in 2017, which turned a contact-happy profile into an offense-happy profile.

I’ll level with you: I’m not sure what went wrong with Tauchman’s power. It’s been “two years,” but the power outage is only 127 plate appearances due to his sparse playing time. The first place I generally look for a power outage is pitch selection, because swinging at bad pitches is an easy way to lose power overnight, but it simply doesn’t seem to be a problem. In his 2019 breakout, he swung at 76.6% of pitches over the heart of the plate. Since then, he’s swung at 79.9% of them, a slight improvement.

His shadow zone swing rate is slightly up (45.4% to 46.9%), as is his chase rate, and both of these feed an increase in swinging strikes. But that hasn’t shown up in his walks and strikeouts, and given that he’s still swinging at pitches over the heart of the plate, the power disappearance remains unexplained.

Here’s one way to frame the problem: In 123 swings at pitches over the heart of the plate in the last two years, Tauchman has cost himself 8.4 runs relative to average. That’s incomprehensibly bad; the league as a whole gains value when it swings at pitches over the heart of the plate, as you might expect. The only player with 100 swings to do worse is Jo Adell, and he did it by striking out 42% of the time with a 20% swinging strike rate.

Is it a swing change issue? It doesn’t appear so. Here he is attacking a center-cut fastball in 2019:

It fell for a triple, but never mind that. Here he is in 2020 attacking a similar pitch:

I went through these Zapruder-style, but I simply don’t see much difference. The timing toe tap is unchanged. He stays compact the same way in both swings, and even finishes the same way. There simply isn’t much to separate the two.

I’m settling on a combination of things. First, I don’t think he’s physically the same as he was in his 2019 season. His sprint speed has declined by 1.6 feet per second, taking him from above average to slow. His home-to-first time has gone up, too — Statcast doesn’t have a mark for him yet in 2021, but it was already slower by more than a tenth of a second last year, and he’s likely declined further this year. By itself, that isn’t indicative of anything, but injury-related decline could both sap him of power and slow him down, so it’s at least a theory.

Second, I’m going to cheat and question how real that power was in the first place. Sure, he cranked 13 bombs in 296 plate appearances, good for a .227 ISO. All of the under-the-hood numbers should have been warnings, though. His 6.3% barrel rate was below league average (7.3%), and it’s one of the best predictors of power. His hardest-hit ball checked in at 109.8 mph; 201 players hit a ball harder than him. His average exit velocity on balls hit in the air (this isn’t actually a predictive stat, I’m just using it for color) was 246th in baseball, sandwiched between Orlando Arcia and Joey Votto (squarely in the singles-only phase of his career at that point).

If his 2019 season had featured, to pull numbers out of a hat, six fewer homers, three more doubles, and three more fly outs, we’d still look at it as a success. He’d still be a 110 wRC+ hitter who the Yankees manufactured out of whole cloth. And he’d still have become worse in the years since; I’m willing to buy the injury story for that.

Tauchman joins a San Francisco outfield in need of a lefty outfield bat. Mike Yastrzemski is ailing, and while he’ll theoretically avoid Injured List time, oblique strains often linger or recur. Their only other lefty option is Alex Dickerson, unless you count switch-hitting Skye Bolt (I don’t). Even Dickerson is off to a poor start; Tauchman will have a chance to seize the big half of a platoon role if he recaptures some of his form.

In exchange for Tauchman, the Yankees got bullpen reinforcements in the form of Wandy Peralta (and also a player to be named later). I searched high and low for a reason to tell you that Peralta is something other than a live lefty bullpen arm with options, and — Peralta is a live lefty bullpen arm with options.

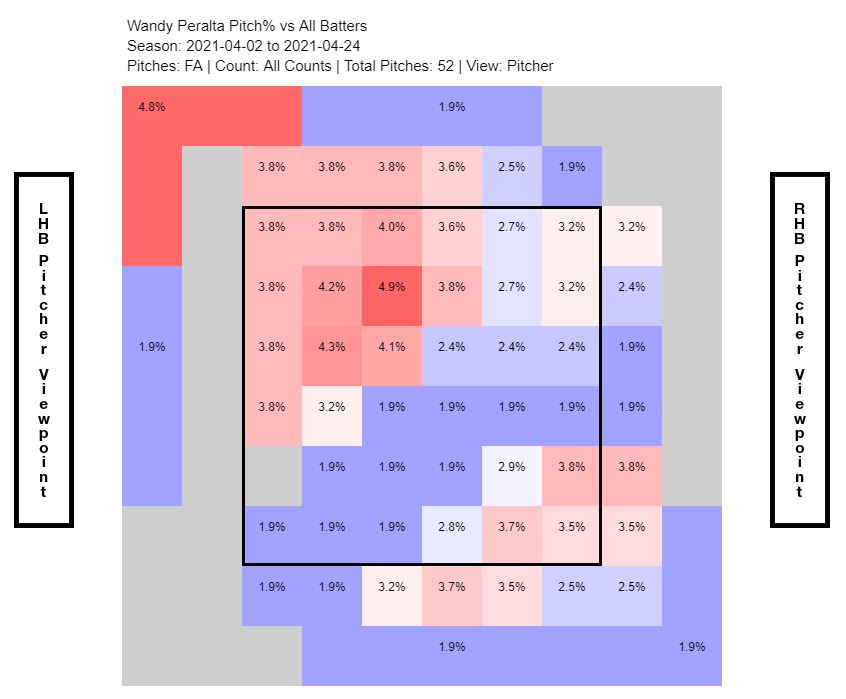

That’s a useful thing! He attacks hitters with his fastball, and while it sits in an uncomfortable location on Kevin Goldstein’s fastball line, he gets enough ride on the pitch to miss the fat part of opposing bats and generate the occasional whiff. He’s commanding it well this year, to boot:

He also throws a slider — yes, another fastball/slider reliever, how original — that is, well, it’s a slider. It’s a weird one, in that it features almost no horizontal break, but it does what sliders do; he throws it down and away to lefties, and it misses bats. The lack of horizontal movement limits its effectiveness, though; he’s actually had more overall success against righties with it despite using it far less frequently. It lacks the bite that makes sliders truly sing in favorable platoon situations.

He also has a wonderful changeup that he throws half the time against righties. It’s a big-breaking pitch that he generally buries low and away, and it’s been his best pitch by linear weights over the course of his career, though his fastball looks much-improved to me this year; it’s harder and features more movement than in any previous year.

I suspect that the Yankees are making a probabilistic bet here, uncertain but hopeful it will work out. Peralta has some interesting pitches, and de-emphasizing the slider or reshaping it slightly might unlock a new level of performance. Throwing your best pitch more often doesn’t always mean breaking balls; he could up his fastball usage and see what happens. I wouldn’t even mind seeing him throw more changeups to lefties as a back-foot put-away pitch, the way pitchers with big-breaking sliders attack opposite-handed batters.

If it doesn’t work out — he has options! The Yankees have proven adept at figuring out adjustments that help their relievers excel, and if Peralta isn’t ready for prime time in his current form, a few months of tinkering in Triple-A might do the trick. That’s not to say he’s going to be their next closer, but a useful bullpen arm? Absolutely!

Both of these teams have front offices renowned for finding value in unexpected places. Neither are dummies; this isn’t a case of one team getting ripped off, selling their quarter for a dime and two shiny pennies. It’s a scuffed quarter in exchange for a differently scuffed quarter. Tauchman has the higher upside if he works out — good position players are more valuable than good relievers. Peralta is more likely to work out — he’s currently missing bats at the major league level and looks better this year. That suits both sides just fine, and I suspect that’s why the trade was made.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Sockman’s swing was always a little suspect to me – to be clear, I loved his pop, and I think his contact-first approach is something that the Yankees desperately need. He’s basically a Gardner-lite; if Gardner wasn’t on the team you’d see Tauch get his playing time.

He found a lot of success in 2019 I think because nobody really had a “book” on him yet, simply as a result of lack of playing time.

That being said, was never a fan of how much he opens his hips when swinging the ball. It’s ripe for abuse by pitchers to go offspeed and totally catch him off-balance.

I think he’s a solid option and I think this is the best possible thing for him, Frazier is scuffling but looks like we’re committed to him as our LF of the future, so it was only a matter of time before Tauchman was shown the door. Wish nothing but the best for him.