Yusmeiro Petit and Chase Anderson Disagree

For the last 15 years, Yusmeiro Petit has cast a spell over opposing hitters. He’s never thrown hard — his highest average fastball velocity was 89.6 mph in 2017, more than a decade into his career. He’s never been an All-Star, never received award votes. He’s been sketchy at times — his rookie season for the Florida (!) Marlins produced a 9.57 ERA. He didn’t pitch in the majors in 2010 or 2011. Through it all, however, he’s kept going, showed up and provided competent innings. He’s almost 36, and it feels like he might pitch until he’s 80.

That consistency is merely an illusion, however. When Petit first made the majors, he was pretty bad against lefties. Most righties get a little bit worse against left-handed batters; they strike out roughly two percentage points fewer opponents and walk roughly two percentage points more. Petit, on the other hand, turned into a pumpkin:

| Split | TBF | K% | BB% | wOBA | FIP | xFIP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vs. L | 1210 | 17.4% | 8.6% | .342 | 5.02 | 4.67 |

| vs. R | 1412 | 25.2% | 4.0% | .293 | 3.46 | 3.62 |

That split is through the end of 2017. I’m now going to do something that I strongly urge you not to do in your investigations of platoon splits — chop them up into smaller pieces. Since the beginning of the 2018 season, Petit’s platoon splits look different:

| Split | TBF | K% | BB% | wOBA | FIP | xFIP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vs. L | 315 | 20.3% | 5.1% | .257 | 4.26 | 4.39 |

| vs. R | 417 | 22.5% | 3.6% | .260 | 3.42 | 4.34 |

It’s a small sample, but I’m inclined to believe it. From 2008 (the beginning of pitch tracking data) to 2017, Petit threw his changeup to lefties 22.1% of the time. Since the beginning of 2018, he’s more or less doubled it, to 41.3%. Changeups are a righty’s best friend against lefties, so the improvement makes sense.

That’s not the only change Petit has made. This one will be easier to show than tell. For example, here’s Petit throwing a pitch to pre-long-hair Anthony Rendon in a relief appearance from 2014:

Here he is throwing to noted father Adam LaRoche in the same game:

They look pretty similar, right? Petit stands all the way to the first-base side of the rubber and lets it fly. Now let’s look at two pitches from 2020. First, a pitch to George Springer:

I’ll be honest — I could have cut that video off about five seconds sooner. I wanted you to see the sweet Matt Chapman defense, but the key part is his position on the mound: unchanged from his pitch to Rendon in 2014. Here he is later in the same game against Josh Reddick:

Wait — freeze and enhance that one:

That’s right — Petit now moves to the complete other side of the pitching rubber to face lefties. The rubber is 24 inches wide, and he releases the ball, on average, 19.5 inches further to the third-base side when he faces left-handers.

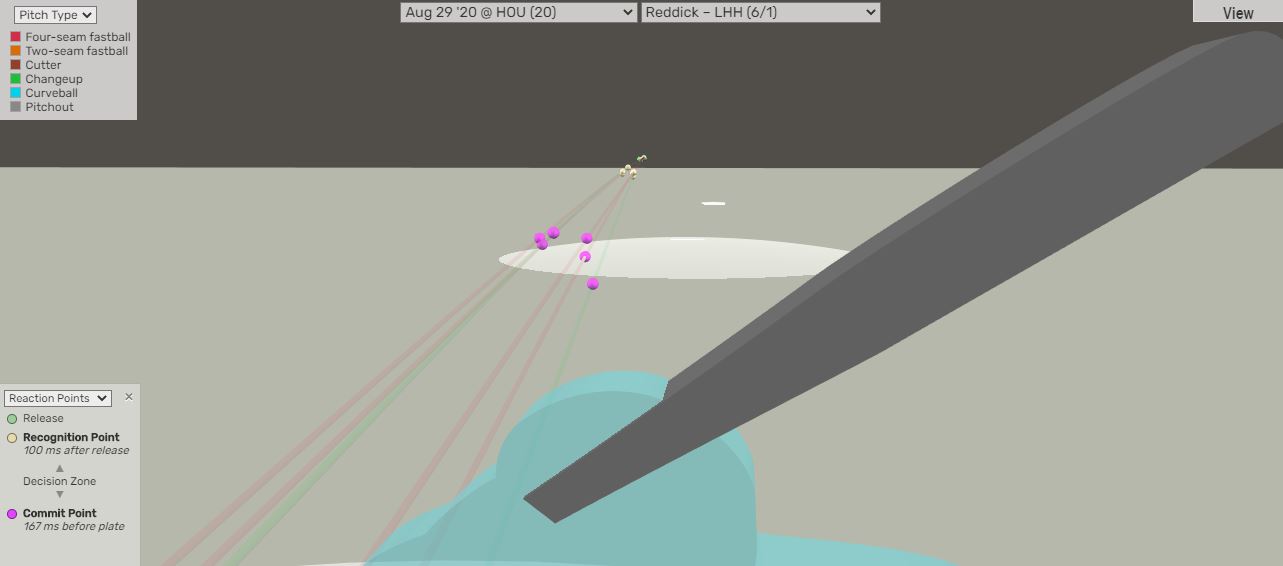

Why? He started trying it out in 2015 on a whim. That was a small change, however, six inches on average. In 2018, he kicked it up a notch to 17 inches on average. Statcast has a handy 3D pitch visualization tool. Here’s how the Reddick at-bat looks to a lefty:

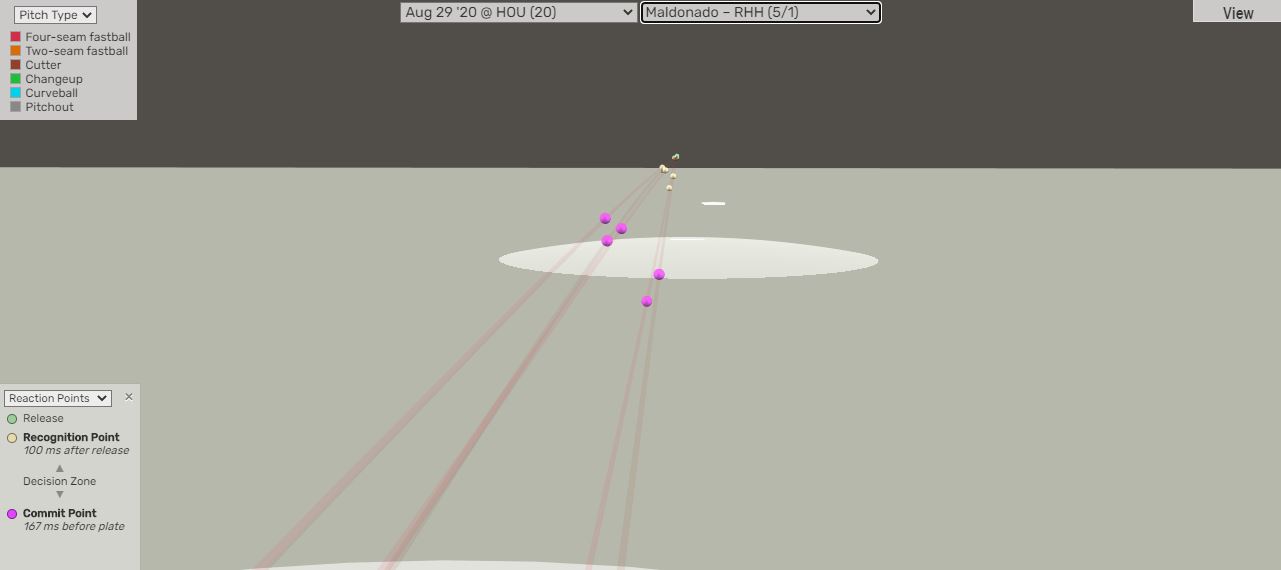

Thanks to the magic of the tool, we can then look at a righty’s at-bat from a lefty’s perspective. Here’s Martín Maldonado vs. Petit in the same game:

It’s a matter of arithmetic and perspective. Petit wants to attack lefties away. From his “normal” extreme first-base positioning, that means throwing the pitch more or less straight ahead — he releases the ball six inches to the third-base side of the center of the plate, the plate is 17 inches wide, he gets only a few inches of arm-side run, stupid geometry, so on and so forth.

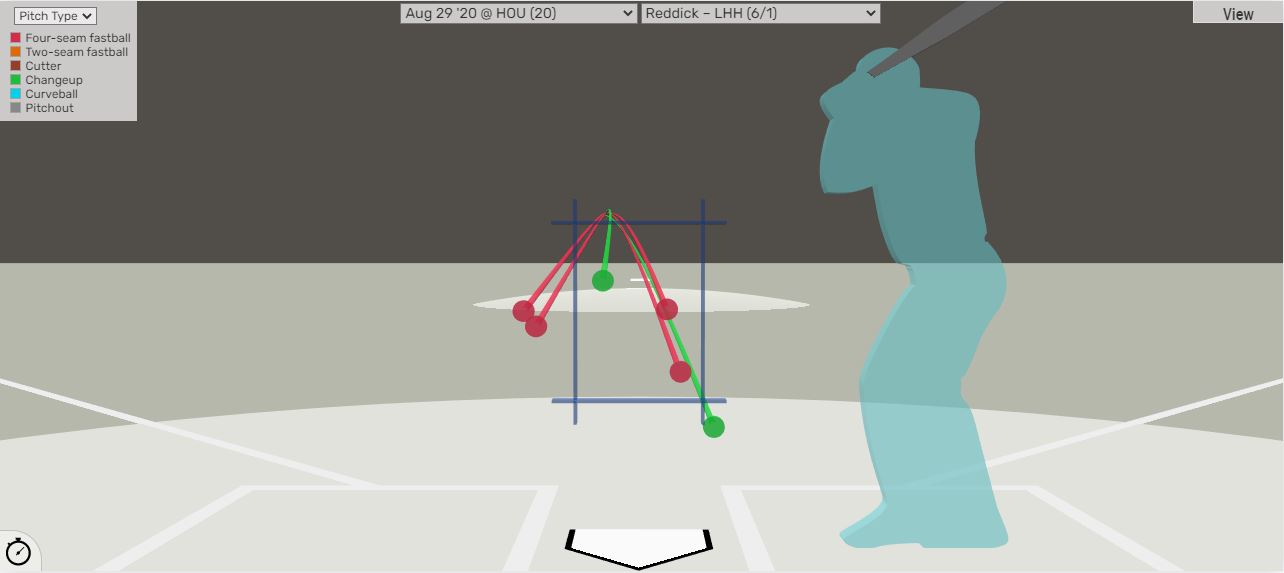

That really dulls how much the pitch appears to break. The two clusters headed Reddick’s way look quite distinct. The high and away one looks like it’s headed towards the middle but tails off the outside corner. The three other pitches look like they’re going to hit him, but two were in the strike zone, and not even particularly inside:

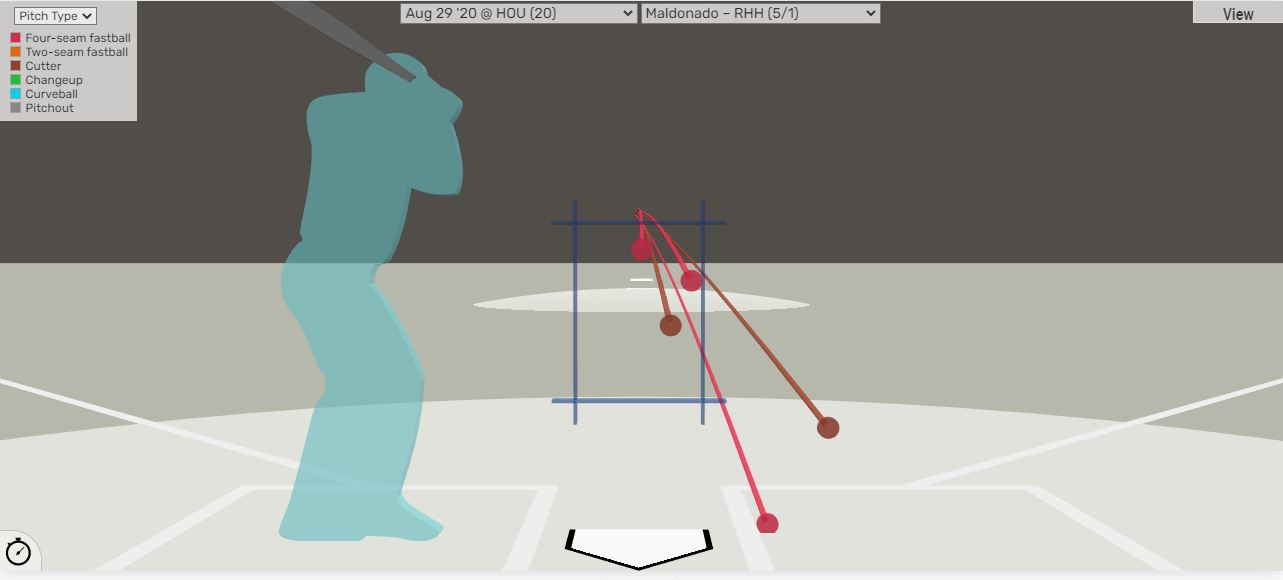

The Maldonado pitches are quite different. The cluster of three that look as though they’re headed toward the middle of the plate finish — well, in the middle of the plate. The two that look inside and low finish inside and low:

This isn’t a change that every pitcher would want to make, but it’s well-suited to Petit’s game. Every pitch he throws to a lefty has arm-side break, and the spots he’s trying to hit look more deceptive from this cross-fire angle. A slider wouldn’t make a lot of sense here; to get it anywhere near the plate, he’d have to throw it more or less straight ahead and let the break carry it, and that would be easier to pick up for a lefty. But Petit, like most righties, doesn’t throw glove-side break pitches to left-handed hitters. It’s simply bad business.

If this is a good way to attack opposite-handed batters, lots of pitchers would be doing it, right? Well, no. Here’s a list of pitchers with the greatest absolute differences in horizontal release point (think moving across the pitching rubber) between left-handed and right-handed batters:

| Pitcher | Release Differential (in) |

|---|---|

| Yusmeiro Petit | 19.4 |

| Matt Strahm | 18.2 |

| Chase Anderson | 11.8 |

| Justin Wilson | 10.3 |

| Tyler Duffey | 8.9 |

| Cy Sneed | 7.6 |

No one else moves by more than five inches. Petit and Chase Anderson are the only two righties who move ten inches or more (minimum 50 pitches thrown to each side of the plate in 2020). But it gets weirder. Here’s Anderson against a righty in J.D. Martinez:

And against a lefty, Alex Verdugo:

Wait — what the heck??

Whatever Petit is doing, Anderson is doing the exact opposite. And guess what? It works too! Anderson is excellent against them:

| Split | TBF | K% | BB% | wOBA | FIP | xFIP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vs. L | 1668 | 20.6% | 8.6% | .296 | 4.25 | 4.62 |

| vs. R | 1992 | 19.9% | 7.1% | .344 | 4.74 | 4.42 |

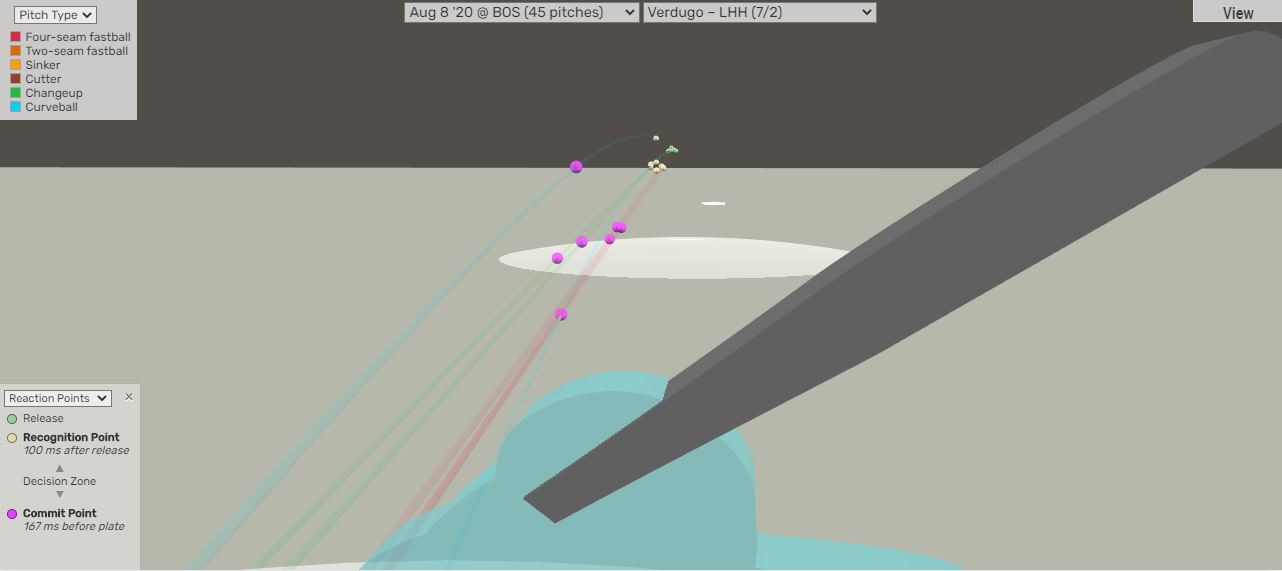

We can try the same pitch perspective trick for Anderson. Here’s the Verdugo at-bat:

The joke here, I suppose, is that Anderson’s changeup has a lot more horizontal movement than Petit’s. The two green lines look quite straight from this angle, but they end up off the plate away:

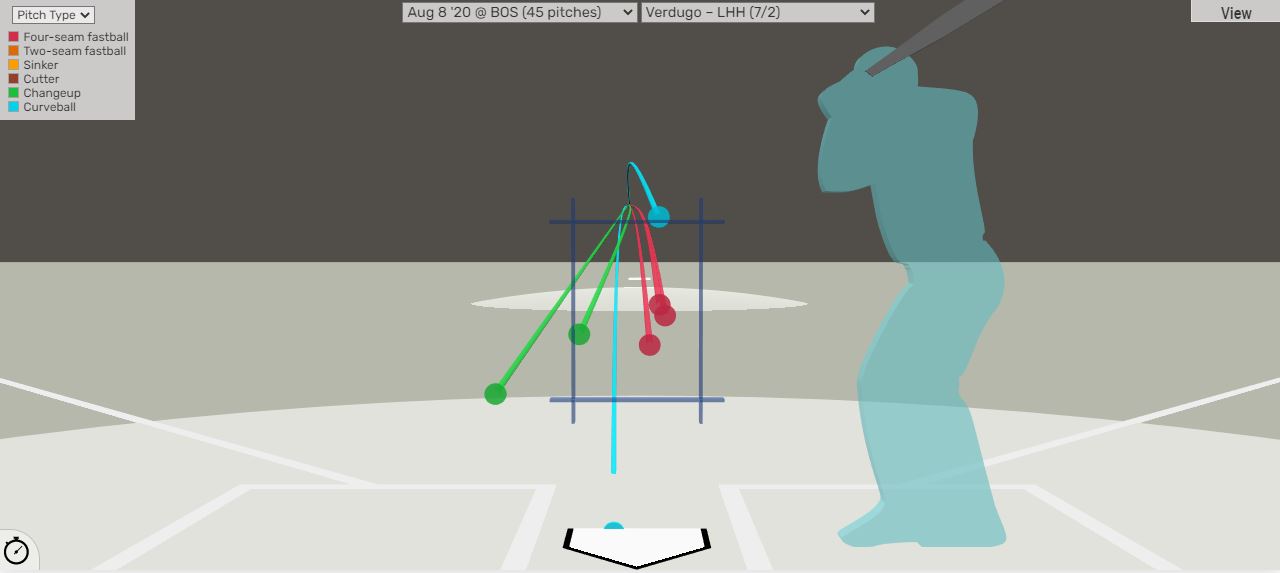

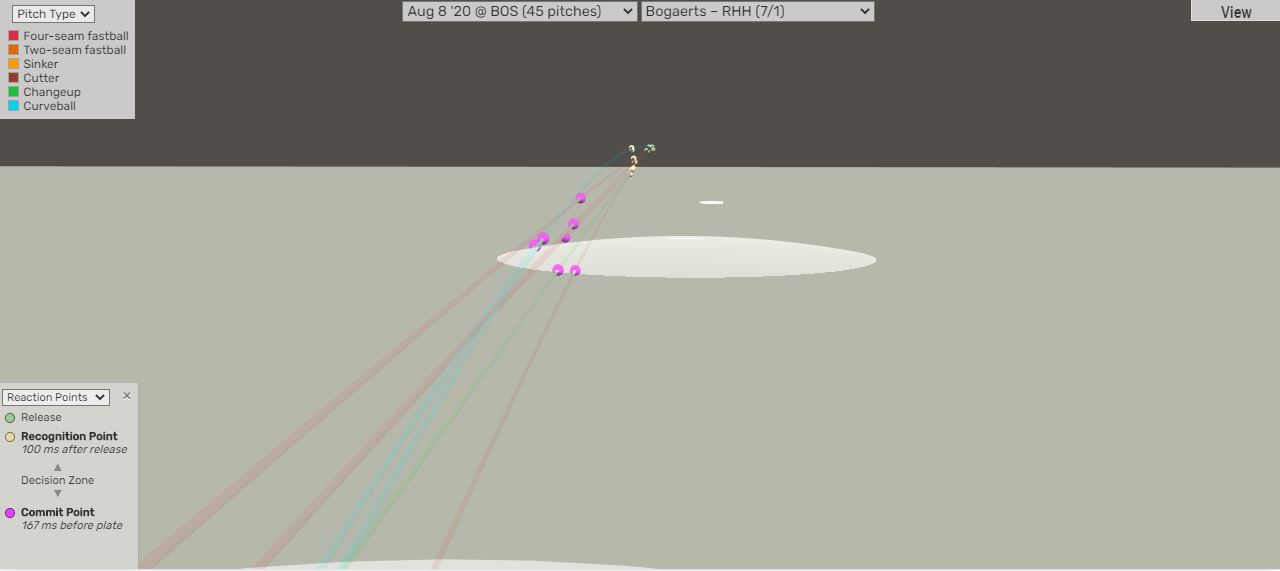

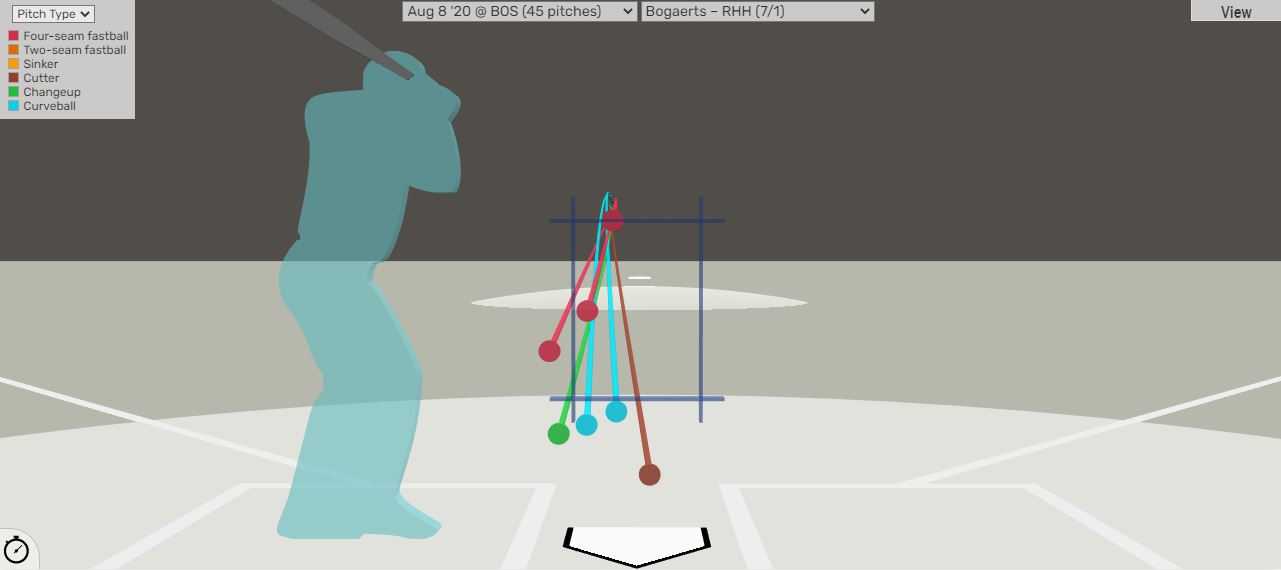

Compare that to what a lefty would see in this at-bat against Xander Bogaerts:

I don’t know. That looks, to me, a lot like the way Petit baffles lefties. The two curveballs, in blue outline, come from a different release point, but the fastballs look suitably confusing. They end up around the zone:

I honestly don’t understand what’s going on here. Anderson, like Petit, fell into using two different starting points. In 2015 and 2016, he didn’t move on the mound at all. He started to drift this way in 2017, and it’s only accelerated since then. His fastball misses more bats against lefties than it used to, while Petit started getting more chases on his changeup from his own travels.

One of them could be right. Both of them could be right. It’s a mystery I don’t feel I’ve cracked, and I’d love to hear what people think about it. But whatever it is, it’s a striking juxtaposition. Two right-handed pitchers in all of baseball (in 2020, at least) hop back and forth on the mound depending on batter handedness. They hop opposite ways. And they both crush lefties. Baseball is wild.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Of all the things to look for when watching baseball I can’t say I would’ve ever noticed this!

It is harder to notice without fans, that’s for sure…