A Dubious Distinction for Yuli Gurriel

The worst thing you can do when you put a ball in play is hit a popup. That’s the worst thing usually, at least: right now, the worst thing you can do is be playing baseball at all, because you plus the opposing team makes 10 people, you jerk. But most times, it’s hitting a popup.

You’ve seen the reasoning for this before, but I’ll quickly lay it out again. When you hit a popup, you don’t reach base. Per Baseball Savant, balls hit with a launch angle of 50 degrees or higher produced a wOBA of .016 in 2019. Given that an out is worth 0 and league-average wOBA is .324, that’s pretty close to being an automatic out. Want it in a triple slash line? If you hit the ball at a 50 degree angle or higher, you bat .015/.015/.022. That’s ugly.

There’s good news, however. Want to avoid popping up and slamming your bat to the ground in disgust? There’s a simple solution: avoid swinging at high pitches. I’m no physicist, but the relationship between high pitches and popups seems straightforward. Your bat is likely to contact the ball from below, there’s some angle-of-incidence angle-of-reflection magic, and bam, Eric Hosmer is camping under the ball. Either that or you get some Alex Bregman magic:

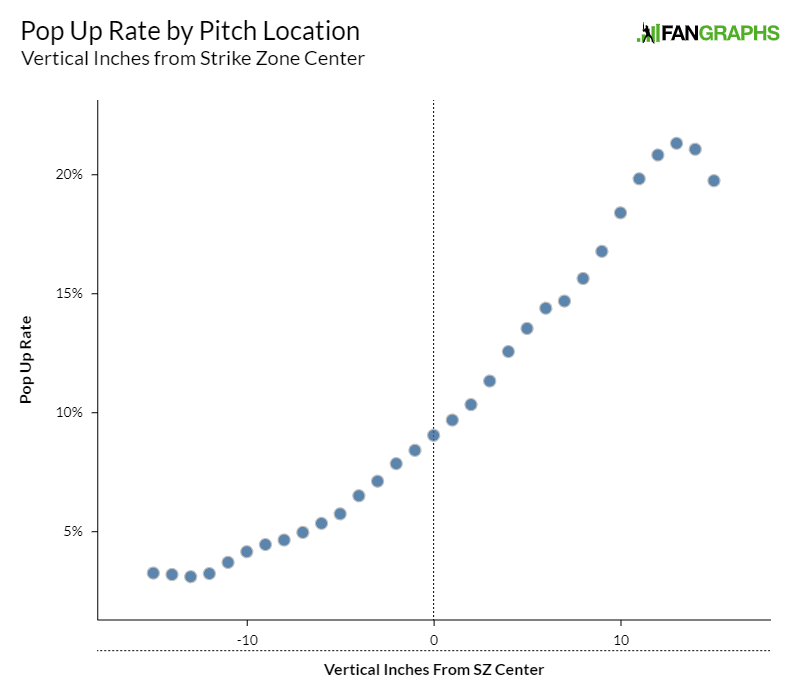

To back this intuition up with data, I downloaded every batted ball tracked by Statcast in 2019. I took each pitch location and grouped them by height. More specifically, I grouped them by height relative to the center of the strike zone; a pitch three feet off the ground can produce pretty different results depending on whether it’s thrown to José Altuve or Aaron Judge.

From there, I asked a simple question for each result: was this pitch hit with a launch angle higher than 50 degrees? If so, I called it a popup. Then I did a little smoothing; I created a range two inches tall for each batted ball with the midpoint at its tracked location. This smoothed and bulked up the data. From there, I just graphed the popup rate for every height relative to strike zone midpoint:

It looks like our intuition was right. Higher pitches, more popups. This is popups only, ignoring all other batted ball types, so this isn’t a value statement about where to swing. It’s simply a statement of fact: swinging at pitches up in the zone is the way popups are made.

At least, that’s mostly how they’re made. None of those points on the above graph are zeroes; in baseball, almost anything can happen if you give it enough time. Sometimes you’re Yuli Gurriel, and you do this:

Or sometimes you’re Yuli Gurriel, and you do this:

Or sometimes you’re… well, you get the idea:

In fact, Gurriel is one of the two worst players in baseball when it comes to popping up on pitches below the middle of the strike zone. Max Kepler is first after he popped up 12.5% of the balls he put in play that were midline or lower, but that’s at least somewhat understandable. Kepler is one of the fly-happiest batters in baseball (his 0.78 GB/FB ratio is the 15th-lowest). He was also quite prone to hitting popups this year; his 15.5% IFFB% placed him fifth among qualifying batters.

Gurriel, meanwhile, isn’t that kind of hitter. Kepler’s trying to hit everything out of the park, and he often succeeds. Gurriel hit more fly balls this year than he had in his career to date, but he’s far less extreme. Kepler is a dead pull, hit-it-high-and-wave-goodbye batter. Gurriel uses all fields and has a nearly-50-point BABIP edge on Kepler for his career. Even in this gruesome low-ball year, his IFFB% was two points lower than Kepler’s. What’s going on?

Would you hate me if I said it was random? That’s an unsatisfying answer to pretty much any question, and it certainly would be to this one. A contact hitter with a career .300 BABIP who can’t stop popping up low pitches? It’s a story that seems too good to be true, and yeah — it’s too good to be true.

For his career, Gurriel has popped up on 8.1% of pitches midline or lower he’s put in play. That’s in the top 10% of all of baseball over that timeframe, but it’s not the outlier you’d expect from his 2019 when he clocked in at 11.3%. So that’s it. Gurriel just got unlucky once, and his popup rate should tick back down, and BABIP rate back up, in 2020.

Well, yeah, not so much. There’s something I’ve left out, like a jerk. Batted balls aren’t separated into popups and everything else. Or, well, they are — but “everything else” isn’t a uniform mass. In his career until 2019, he’d put 614 balls in this midline-and-below region into play and gotten 16 home runs for his troubles. He’d produced a .311 wOBA on those balls in play; quite poor despite the lack of popups.

In 2019, he put 282 such balls into play — and got 11 home runs out of the bargain, nearly double his previous rate. He managed a .343 wOBA on them, a significant improvement (though the league improved as well, from .307 to .315), on similar pitches. And the change in approach was evident; in his previous career, Gurriel’s average launch angle on these low balls was 6.4 degrees. In 2019, it spiked to 11.5 degrees.

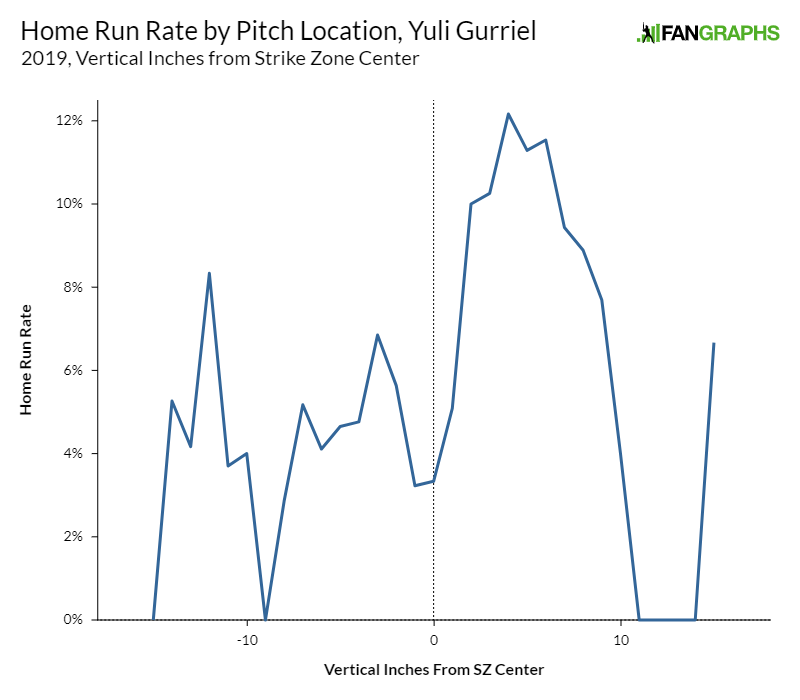

Let’s look at that popup density distribution again, only this time with home runs instead of popups:

The y axis has different numbers, but the shape looks pretty familiar. Most hitters have more home runs in the higher regions of the plate. The only difference is the gentle slope down starting around six inches above the midline, and that’s understandable; it’s hard to hit those pitches at an optimal angle.

Here are two last graphs. The first is Gurriel’s home run rate by pitch height from 2016 to 2018:

This isn’t a crazy graph. People don’t really hit home runs in this region; even in 2019, they turned 5% of batted balls below the dead center of the strike zone into home runs. Gurriel was at about 3% before 2019 with a less lively ball. Then after more launch angle, a rabbit ball, and more homers, he grew that number to roughly 4.5% in 2019:

He paid for the popups, in other words, with a few extra home runs. The data is jagged, as you’d expect with such a small sample size, but the axes are the same, and you can see the across-the-board increase. So in the end, maybe my distinction between Gurriel and Kepler doesn’t make sense. Kepler certainly looks the part of a power hitter more.

But Gurriel cranked 31 homers in 2019, and he did so with a career-high ISO, wOBA, barrel rate, HR/FB%, and fly ball rate. He did that by hitting more home runs on low pitches. You can accept a few popups if you’re going to do this:

In the end, the story of Yuli Gurriel the sudden popup hitter isn’t as weird as it first sounds. It’s really the launch angle revolution all over again. A batter who was performing worse than he wanted to when putting the ball in play made a decision to put it in the air. It bit him some, sure: he hit five more infield fly balls in 2019 than he had in any previous full season. It particularly bit him low in the zone when it came to popups. But the rewards more than covered the cost. Or at the very least, they broke even: his xwOBA on those low balls in 2019 was basically unchanged, with more homers and free outs balancing out.

Yuli Gurriel has a dubious distinction; he hits popups on pitches he shouldn’t be able to get under. But that distinction is just a skill in disguise. He’s learned to turn some of those low pitches into slow jogs around the diamond. In a game of tradeoffs, he’s made a seemingly effective one. All that remains to be seen is pitchers’ reactions to the new Gurriel in 2020.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

How about the take-charge leadership and Gold Glove worthy defense on that first clip?