A Time to Slug, and a Time to Bunt

In August, the Phillies hit 59 home runs, which is the highest total for a month in franchise history and tied for the third-highest total in any single month by any team in history. It was a remarkable performance, but perhaps not a particularly surprising one given how this roster was constructed; by design, Rob Thomson’s charges are large, strong, and (of late) increasingly shirtless. They were born to mash.

Last week, I had the good fortune to be present at Citizens Bank Park as five of those 59 home runs took flight in a single evening, off the bats of five different Phillies. This was one of those close, muggy summer nights that define the mid-Atlantic summer; with a pleasant, gentle breeze blowing out to left field, the ball was roaring out of the park. It wasn’t just the Phillies; the Angels dingered three times themselves. Two of those came off the bat of Luis Rengifo, hardly a man whose public stomps and chants are included in the Home Run Derby every year.

But as the Phillies laid 12 runs on their opponents, the play that stuck in my mind was the opposite of a home run. In the sixth inning, the Phillies batted around and scored six runs to turn a 4–2 deficit into an 8–4 lead; one of those came on a squeeze bunt by Johan Rojas. It was a lovely push bunt by a speedy right-handed hitter, the baseball equivalent of spreading room temperature compound butter on a slice of crusty bread. “Man, we should see that more often,” I thought to myself.

I cut my teeth writing about college baseball back when the sacrifice bunt was an automatic action whenever there was a runner on first and/or second base with less than two outs. I thought then, and still believe now, that in most cases an overreliance on the sac bunt was a self-defeating action brought on by managers (or coaches, at the college level) who wanted to feel like they had control over an inherently chaotic game.

Back then, I got a bit of a reputation for being an anti-bunt crank, which isn’t completely accurate. I hated the stubborn insistence that the smart thing to do was almost always to trade an out for a base (if said bunt was properly executed correctly, which was far from a given). My little scarcity-obsessed animal brain could not get on board with spending one of a team’s most precious resources (its 27 outs) for such a meager reward, particularly when all available empirical evidence revealed the regular sacrifice bunt to be even more foolish than most people thought.

But I have always loved the surprise bunt attempt for a hit, the bunt against the shift, the suicide squeeze. Sometimes the bunt is genuinely the right play, and bunt attempts for a hit reward daring and speed, two attributes that are too infrequently rewarded in this game.

Bunts are like dill. Sometimes dill is the right herb for a given situation. Sometimes, tasting dill in an unexpected food — potato chips, most notably — can be positively invigorating. But you don’t want to use too much dill or in every dish you cook. There’s a time and a place.

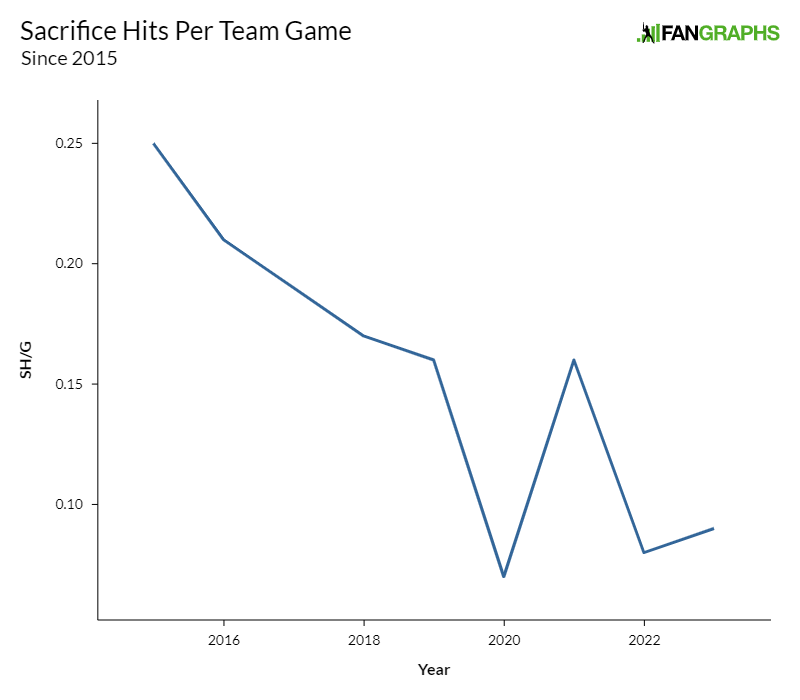

Sure enough, teams have been using the sacrifice bunt less and less since 2015:

Some teams have essentially eschewed the sac bunt forever. The Braves have laid down only three in the past two seasons put together, which makes sense, because as good as Atlanta’s lineup is, advancing a runner one base at a time is practically stopping to smell the roses.

The fact that the sacrifice bunt has fallen so far out of favor so quickly is first and foremost evidence that sabermetric best practices are now fully integrated into most managers’ tactical thinking. The Dill Doctrine, in other words, is in effect. But it’s also important to remember that taking the bat out of pitchers’ hands has knocked several hundred sacrifice bunts out off the league each season. In the three seasons in which MLB has employed a universal DH (2020, ’22, and ’23), the only pitcher bunt on record is a Shohei Ohtani bunt single last year.

| Season | P Bunt % | P SAC% |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 27.2% | 40.5% |

| 2016 | 29.4% | 43.8% |

| 2017 | 32.7% | 50.8% |

| 2018 | 31.4% | 49.7% |

| 2019 | 35.5% | 55.6% |

| 2020 | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 2021 | 37.4% | 54.9% |

| 2022 | 0.1% | 0.0% |

| 2023 | 0.0% | 0.0% |

Even then, you can see the decline of the sacrifice bunt in these numbers. One of the few scenarios in which the automatic bunt was actually called for involved a pitcher hitting with men on. As the 2010s wore on, those situations made up a progressively larger share of sacrifice bunts and bunt attempts in general. In 2015, pitchers accounted for a little more than a quarter of total bunt attempts put in play and 40.5% of sacrifice bunts. By 2021, more than a third of total bunt attempts in play, and well over half of sacrifice hits, came off the bats of pitchers.

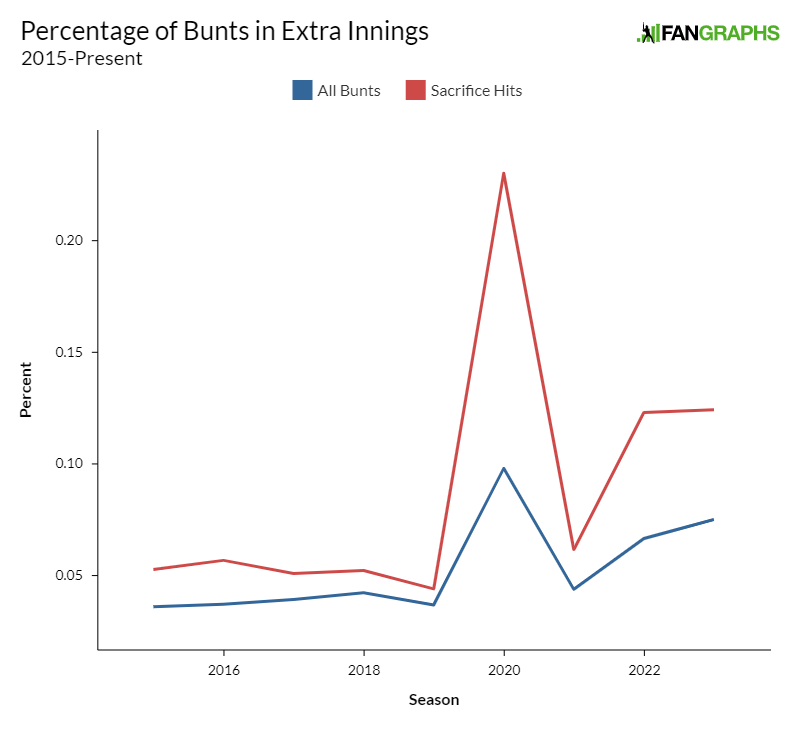

The other pandemic-related rule change was the addition of the bonus runner on second to start extra innings. If ever there were a situation that made a sacrifice bunt reasonable under the Dill Doctrine, it’s runner on second, no outs, one run likely wins you the game. And sure enough, a greater percentage of bunt attempts take place in extra innings now than they did before the universal DH and the bonus runner.

Before we go any further, I want to make a few points about the statistics around bunting. In order to get the full picture, I’ve had to cobble together data from our splits leaderboards, plus searches on Baseball Reference’s Event Finder, as well as Baseball Savant. The splits leaderboards don’t include strikeouts on bunt attempts, and why would they, as a strikeout isn’t a batted ball? And sacrifice hit leaderboards don’t take into account sac bunts, like the one Rojas laid down against the Angels, that end with the batter reaching and the runners advancing but get scored as a fielder’s choice and not a single.

When determining the value of a bunt, the number to look at is batting average. Obviously no bunt goes down as a walk, and sacrifices don’t count as an at-bat. Occasionally, a bunt will go for a double, but not frequently enough to be statistically interesting. There have been eight bunt doubles since 2015, and while they’re of limited empirical value, they’re all good for a laugh.

The sticking point here is that sacrifice bunts don’t get counted against a hitter’s OBP either, because for God knows what reason, a sacrifice bunt is considered to be a manager’s prerogative and not a useful data point for player evaluation. This is the official MLB party line, and whoever made this decision deserves to wake up every morning to find their underpants full of mosquitoes.

So in order to figure out how much better the league is at bunting now than a few years ago, I’m going to throw a few numbers at you. The first is batting average, strictly on batted balls measured as bunts. The second is bunt success rate, which is bunt hits plus sacrifice hits divided by plate appearances (balls in play and strikeouts) that end on a bunt attempt. The third is bunt OBP, or bunt hits and no-out fielder’s choice plays (like the Rojas bunt) divided by total bunts and strikeouts on bunt attempts. And finally, because I’m feeling a little licentious after the OBP thing, is a version of bunt OBP that punishes hitters with an extra out if they hit into a double play.

| Season | AVG | Success Rate | Bunt OBP | Special Bunt OBP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | .403 | 64.2% | .208 | .205 |

| 2016 | .399 | 62.8% | .212 | .209 |

| 2017 | .398 | 63.4% | .213 | .210 |

| 2018 | .397 | 60.7% | .224 | .222 |

| 2019 | .417 | 62.7% | .221 | .218 |

| 2020 | .482 | 63.2% | .353 | .353 |

| 2021 | .382 | 61.3% | .197 | .195 |

| 2022 | .523 | 66.8% | .357 | .356 |

| 2023 | .509 | 67.0% | .333 | .332 |

(By all means, get up and stretch your legs if you’ve just read “bunt” so many times in the span of a few paragraphs that it’s making you giggle.)

Back before the universal DH got implemented, fans of the idea would go on and on about how terrible pitchers are at the plate. And it’s true: pitchers have gotten worse at hitting, relative to the league, over time. Turns out they stank at bunting, too, because with pitchers out of the equation, a bunt — even saddling the batted ball type with the millstone that is the sacrifice — turns out to be a decent context-neutral play.

| Season | SO | GDP | P AVG | Pos. Player AVG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 175 | 34 | .090 | .459 |

| 2016 | 164 | 39 | .087 | .464 |

| 2017 | 141 | 29 | .074 | .463 |

| 2018 | 148 | 24 | .071 | .468 |

| 2019 | 148 | 27 | .121 | .485 |

| 2020 | 8 | 0 | .087 | .482 |

| 2021 | 174 | 19 | n/a | .461 |

| 2022 | 35 | 3 | 1.000 | .522 |

| 2023 | 18 | 4 | n/a | .509 |

Not only have aggregate results improved, but the worst-case scenarios on bunt attempts have also all but disappeared. There have only been seven bunt double plays in a little more than two normal-length seasons’ worth of universal DH, and strikeouts on bunt attempts have dropped into the low double digits. Position players are faring better on bunts than they did a few years ago, but not by a ton.

I’ve always been amused by the ways in which arguments or trends in sabermetrics get repeated nearly verbatim in other sports with less mature empirical traditions. Here, I think we’re seeing the reverse. A few years ago, the stat nerds in basketball established that the two best shots you could take, in terms of bang for your buck, were dunks and three-pointers. So analytically focused clubs, like the Houston Rockets under Daryl Morey and James Harden, were optimized for that approach. (“Whatever happened to those guys?” asks the absolutely miserable Sixers fan in 2023. “Did they end up winning a ring?”) Mid-range and long two-point jump shots were ridiculed as obsolete, the way we talked about the bunt 10 or 20 years ago.

What the basketball big brains came to realize, though, is that while the two-point jump shot is an inefficient use of a possession in the aggregate, it can be quite profitable under the right conditions — specifically, if the person shooting it is reliable from that range, and if the defense is leaving that shot open in order to protect the rim and the arc. That’s where baseball teams seem to have ended up on the bunt. In the right hands, and in the right situation, it can be the best shot on the court.

All stats current as of Sunday, Sept. 3.

Michael is a writer at FanGraphs. Previously, he was a staff writer at The Ringer and D1Baseball, and his work has appeared at Grantland, Baseball Prospectus, The Atlantic, ESPN.com, and various ill-remembered Phillies blogs. Follow him on Twitter, if you must, @MichaelBaumann.

For whatever reason, this made think about the idea of Giancarlo Stanton bunting, which is rather hilarious, because I’m pretty sure he’d still have an 80+ EV on a bunt somehow.

If Spencer Torkelson can get a ~100 EV on an HBP…..