Alex Bregman’s Triumphant Non-Adjustment

Maybe this isn’t charitable, but I picture Alex Bregman as being a lot like me. See, when I play a game – whether a sport or a board game – I’m always thinking about the most efficient way to win, what game actions are the most valuable, and how I can do those things more often. The best games don’t have clear best options at all times, but there’s almost always some strategy you can lean on to get ahead, and I greatly enjoy figuring that strategy out.

Bregman treats baseball like I treat Taverns of Tiefenthal, my favorite board game. He knows what the most valuable things to do in baseball are, and he does them more frequently than everyone else. If you look at his Statcast page, you’ll come away unimpressed. Hard hit rate? He’s in the 42nd percentile across the majors, below average. Think that hard hit rate is misleading? He’s average when it comes to maximum exit velocity (53rd percentile), barrel rate (50th), and even average exit velocity (59th). He’s well below average in sprint speed. It doesn’t sound like he should be an outstanding hitter, at least by the measurables.

Early in Bregman’s career, that would have been a laughable claim. He totaled 16.2 WAR on the back of a 162 wRC+ between 2018 and ’19, staking a claim as one of the best hitters in the game. But in the next two years, both injury-shortened, he fell back to earth. His .261/.353/.431 line was good for a 115 wRC+, a far cry from his earlier form. Was he a creation of the juiced ball? Sign stealing? Did pitchers figure him out?

This season would suggest otherwise. After a slow start – midway through June, he sported a 104 wRC+ – he’s gone on an absolute tear. His seasonal line now stands at .261/.365/.466, good for a 139 wRC+, and he’s quickly climbing every offensive leaderboard imaginable. He’s already compiled 4.1 WAR on the season, nearly double last year’s output and 18th among all hitters. He hasn’t done it by getting stronger or anything like that. He’s simply doubled down on what he was always best at: making the most of his own talents.

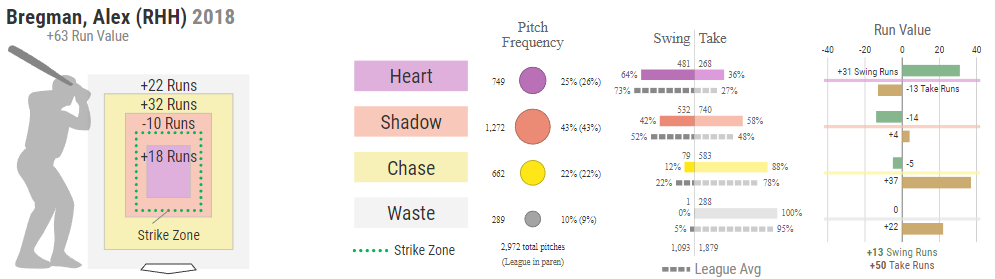

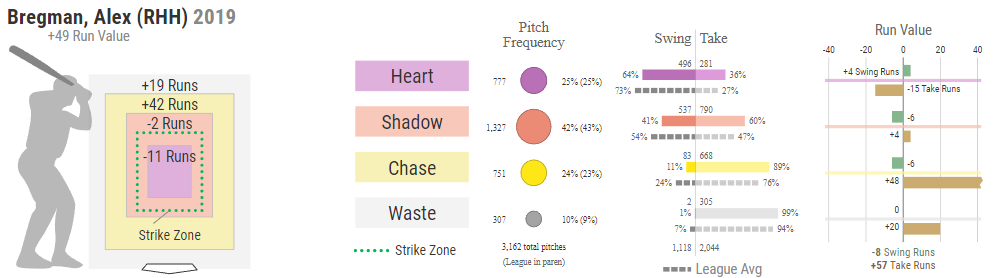

Bregman has always been a phenomenally disciplined hitter. Via Baseball Savant’s swing/take charts, we can show that graphically. Here he is in his superlative 2018 season:

That’s great work, and the reason it’s great work is obvious. That year, he simply didn’t swing at bad pitches. He chased bad pitches at roughly half the league average, and laid off plenty of pitches in the shadow zone as well. Sure, he took too many pitches thrown over the heart of the plate, but he did enough with the ones he swung at to make up for that. That’s a tradeoff that made even more sense considering Bregman’s modest raw power; he wasn’t giving up on Yordan Alvarez-level production on those balls anyway.

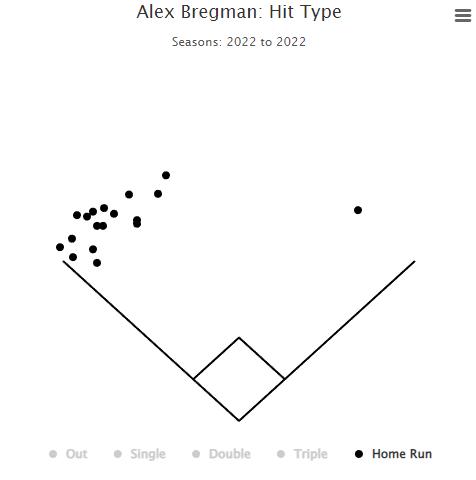

When he did swing at those juicy pitches, he was mostly trying to do one thing: pull them over the left field wall. That worked quite well for two reasons. First, everyone was a slugger in 2018 and ’19, the peak years of the home run explosion. Second, Houston’s ballpark is uniquely suited to Bregman’s gambit; the short left field porch means that plenty of balls that would have been lazy outs anywhere else left the yard.

Bregman has the purest form of pull power, aided by the stadium. In his career, he’s homered on 18.4% of the balls he has put in the air to the pull side. That includes all line drives, fly balls, and popups, not merely balls hit at ideal home run angles. When he goes to the opposite field or to center, that number falls to 2.7%. Don’t just say it’s a wall thing, either: he has hit 30.2% of his pulled air balls 100 mph or harder, double the rate at which he exceeds 100 mph when going up the middle or the other way.

That’s how Bregman operates when he’s at his best. In 2020 and ’21, he kept doing the same, but with reduced efficiency. He controlled the strike zone as well as ever, but wasn’t getting the power production that keyed his strong seasons. His approach depends heavily on hitting a steady diet of pull-side balls at homer-friendly angles. Those average batted ball metrics I mentioned above are already better than his raw power; his power plays up when he pulls the ball, in other words.

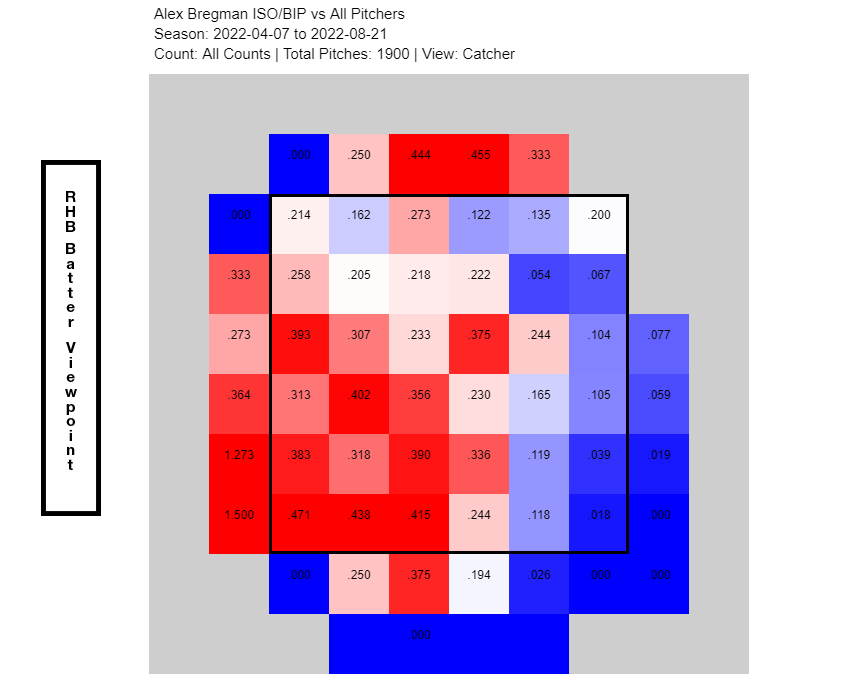

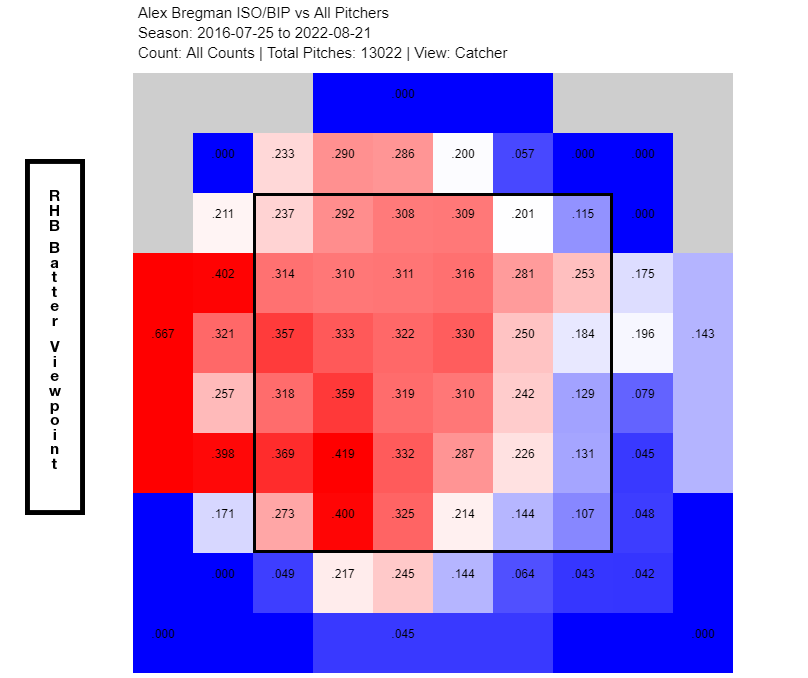

As you might expect from someone who gets all their power from pulling the ball, Bregman is at his best when he can turn on the ball. Here’s his isolated power on balls in play this year:

And while the extremes of that graph are partially due to sample size, it’s the same deal for his career as a whole. Inside and low, he’s ready to go. Away? He’ll try another day:

When he’s going right, a ton of those swings result in pulled, lofted balls that he hits 95 mph or harder. You won’t be surprised to learn that in his best years, Bregman produced a ton of those particular batted balls. What might surprise you, though, is that he’s nearly back to that clip this year, and that he’d already started to rebound there last season.

In fact, Bregman’s return to the top has mirrored his earlier ascent. How is he managing his amazing line? He’s just doing the same things he’s always done. Pull everything? Take a look at his home runs this year:

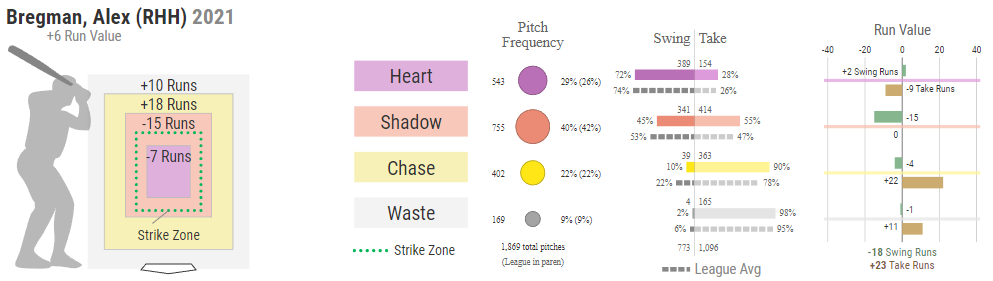

Swing decisions? He’s actually better than he was in 2018 and ’19 there, at least in terms of swinging at pitches over the heart of the plate while avoiding waste elsewhere:

One difference you might notice: Bregman isn’t actually adding much value by swinging at those pitches over the heart of the plate. Only three swing runs added despite swinging at so many cookies? He did far better than that in 2018, as we saw up above. But here’s a secret: that 2018 season was never very likely to repeat itself. He massively outperformed anything he’s done since in terms of production on contact. Even in his excellent 2019 season, his results when he swung at good pitches were only fair:

Compare 2022 to ’19, and Bregman’s process looks better. Sure, fewer balls are leaving the yard; as a dead pull, all fly-ball hitter without Judge-ian power, that was always going to be the case given the changing composition of the baseball. But if you’re looking at process, Bregman is doing a good job maxing out, like he’s always done.

In fact, here’s something interesting. He was already doing this last year:

What are we missing? Bregman was bad by his standards in 2021. He took the same process into 2022, and now he’s succeeding again? Sure sounds like I’m being too results-oriented in my evaluations.

Consider this, though: Bregman is healthy for the first time since 2019. In 2020, he dealt with persistent hamstring issues. Last year was even worse; he missed 58 games with a quadriceps injury, then played through a nagging hand issue that required surgery after the end of the season.

Lower-body issues are bad enough for your swing; throw in a hand injury, and perhaps it’s no surprise that Bregman’s contact quality suffered. He set a career high in groundball rate and a career low in line drive rate, the exact opposite of what he wants to do at the plate. When he did manage to lift and pull, he did just fine – he simply couldn’t do what he wanted to often enough.

One more thing is worth mentioning. When Bregman was at his best, he flat out destroyed breaking balls in the strike zone. He slugged above .700 when he put them in play in 2018 and ’19, and that didn’t leave pitchers with many options. Throw something bendy out of the zone, and he’d spit on it – he has one of the best eyes in the game. Throw him one of those pitches in the strike zone, and he’d probably watch it fly by – but if he didn’t, he was liable to deposit it in the seats.

That all fell apart over the last two years, and it was all part of the same problem; where he’d previously been excellent at elevating those pitches, he started pounding them into the ground. This is a really silly and specialized statistic, but I don’t think that makes it less meaningful. Take a look at his groundball rate on breaking balls in the strike zone, as well as his wOBA and slugging percentage on them:

| Year | GB% | wOBA | SLG |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 40.7% | .396 | .632 |

| 2018 | 30.1% | .456 | .710 |

| 2019 | 26.2% | .443 | .827 |

| 2020 | 30.4% | .293 | .435 |

| 2021 | 41.3% | .346 | .540 |

| 2022 | 31.4% | .496 | .800 |

That old bind is back again. Pitchers can’t throw him one of those pitches and expect to get away with it. That limits their options; there’s a reason he’s only striking out 12.4% of the time this year while walking 12.9% of the time. The in-zone breaking ball is one of modern pitching’s greatest weapons. Heck, the increased use of breaking balls in general is one of the great advances of recent pitching analysis. When it doesn’t work against a hitter, pitchers are left without options.

So what is Bregman doing of late that’s working so well? The same thing he’s always been doing: lifting and pulling everything he can get his hands on, taking everything he can’t, and generally maxing out his performance beyond what anyone could reasonably expect. This time, he’s just doing it while healthy.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Pulled flyballs are also less affected by the increased drag on the baseball compared to oppo flyballs, making Bregman more immune to the deadened ball.

Both more immune and less immune, fascinating!

I’m not saying you are wrong, but arguments about specific players playing better/worse with juiced/deadened balls are more ad hoc than people realize.

Just two months ago, people on this site were talking about how Bregman was a beneficiary of juiced balls.

Chop the sample into small enough pieces and you can tell a reasonable sounding story about why a hitter is doing better/worse because how the ball changed.

But the reality is much more complicated.

Normal variance of athletic performance is already so high that a sample size of one player is unlikely to tell you much about the bigger picture except about that athlete.

This wasn’t necessarily a post hoc justification for his performance, but something I noticed while exploring changes to the ball over the offseason, see my post here, in fact, Bregman is mentioned in the conclusion of that post.

Believe me, I dislike the post hoc rationalization of player performance based on random variation as much as you do! I wrote another post about how pitcher release point changes don’t really correlate to performance changes because they get used as justification all the time.