An Incomplete Study of Pitchers in Blowout Games

On Tuesday, the Brewers beat the Cubs 11-1. It was the 71st game this season decided by 10 or more runs, and the 183rd decided by eight or more, and it got me thinking about failure. Baseball has an awful lot of failure. So much, in fact, that it feels sort of trite to mention it. It’s mostly failure of the small, survivable variety. We learn a lot from those sorts of tumbles. It makes our moms worry, but life’s lessons generally come after we’ve strung a bunch of snafus together. The how and why of a pitcher getting lit up, or a defensive alignment not working, enhances our understanding of the game, even if just to say, “Well, don’t do that again.”

But baseball also does big failure, extreme failure. Baseball does blowouts. Some of them come early, while others develop late. Sometimes they’re the result of a series of foul-ups; other times it’s one big inning. But in their extremity, we learn something about the everyday. So I took a look at blowouts, adopting pitchers as our guides through this land of suck, to see what we might discover. I present a not-brief, incomplete study.

The Reliever Whose Boss Only Cares About Him a Little

One of the crueler things about blowouts, and baseball more generally I suppose, is that no matter the score, someone has to pitch. The game doesn’t believe in mercy; the game believes in wearing one. We’re used to feeling the cruelty of a starter who has to stay in down seven runs to save the bullpen. It’s natural to feel sympathy for someone having a bad day. But cruelty isn’t the exclusive province of losers; there’s a smaller meanness reserved for victors, too.

The only real requirement for a pitcher on the right side of a blowout is that he not fail too much. Fail too much, and the manager has to get another guy up. Too much, and suddenly those soon-to-be losers for whom we were feeling so bad are back in it. Too much, and the fans who were previously comfortable start to feel nervous. But that’s the extent of our, and the manager’s, concern.

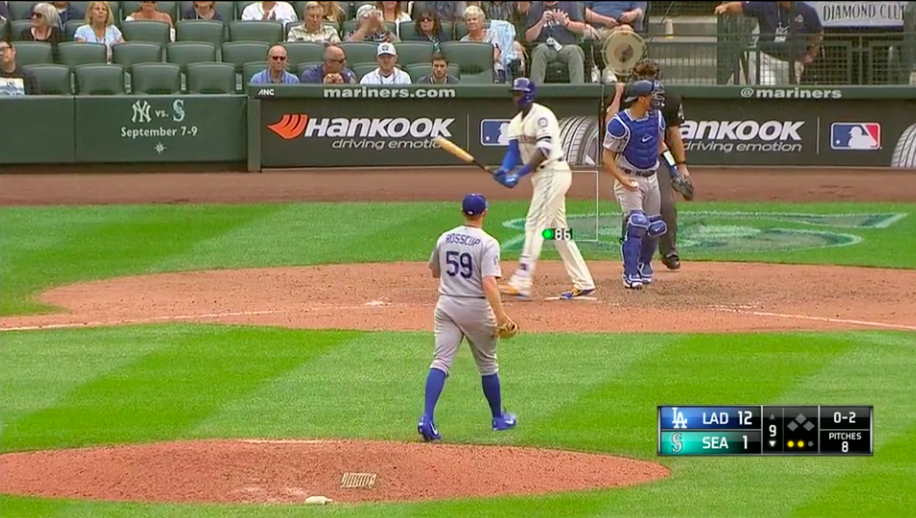

Beyond the worry of too much failure and possible injury, it didn’t really matter what Zac Rosscup did on August 19, when he was called on to pitch the ninth with the Dodgers up 12-1 against the Mariners. There’s something unkind in that indifference. This is a person’s day, after all, and aren’t we conditioned to ask about those, even when they belong to strangers? We might only ask as a matter of form. Perhaps we’re only being polite. But our insistence on manners suggests we think we ought to care, or at least look like we do, even if we can’t muster much more in response than a curt nod.

On this particular Sunday, the malaise even extended to something extraordinary. Rosscup, facing Kyle Seager, Ryon Healy, and Cameron Maybin, threw an immaculate inning amidst all that indifference. It was just the fourth such inning this year, and I think the only person who noticed at the time was Austin Barnes.

Here he is, looking at the dugout as if to say, “Guys! Did you see that!?”

But we get no indication they did. Neither booth mentioned it. The SportsNet LA broadcast showed us all of Barnes congratulating part of Rosscup on a job well done…

… but made us look at two whole butts before they did.

Butts aren’t what you show when you want to mark an occasion. Butts aren’t serious. These butts look like walrus faces if you squint. Sorry, butts.

Someone has to pitch, even when the game is effectively over and has been for a while. It’s a mundane, plodding sort of business, with very little glory to it, defined by the manager’s lack of care. And so I’m happy Austin Barnes seemed to notice what Zac Rosscup did.

Work is so much easier when you have a friend, especially when there are butts around.

The Reliever Who Really Mucks Things Up

It’s hard to watch other people fail and not feel at least a little bit bad for them. Of course, with baseball being what it is, we spend a lot of time bearing witness to the failings of strangers. We mostly do okay with it; we learn how to compartmentalize, lest we be overrun, doomed to feel ceaselessly. Sometimes, though, things get wonky. Sometimes, players’ tribulations go beyond the ho-hum of normal failure and make us squirm.

To wit: on July 21, Austin Bibens-Dirkx came in to relieve Bartolo Colon and promptly gave up a two-run shot to Yonder Alonso. That’s fine. That happens! But it didn’t end there. Of course it didn’t. I’m telling you a story about the stuff that makes us wriggle.

After Austin plunked Yan Gomes in the sixth, he gave a disappointed shake of his head, as if to say that this wasn’t how he wanted his night to go. He looked sad, but he didn’t know what sadness was yet. It was just a blast and a bonk. He was still failing normally.

But then came another two-run homer, this time to Tyler Naquin, and something shifted. We entered a new condition. When Alonso hit his second home run, I hid my eyes and felt a sudden urge to run the vacuum. This wasn’t normal failure. This was hands-on-your-knees failure, weigh-you-down-from-above failure. This was, in the space of four innings, the sort of failure that feels mean to mention. It’s the sort that makes us squirm.

The metaphor for which we reach most often in moments like this is a car crash, simultaneously awful and captivating, but I don’t think that gets it quite right. It’s tempting when a pitcher manages to give up 11 runs, as Bibens-Dirkx did, but there comes a point when the enormity of the screw-up loops all the way back around from an accident on the side of the road — with people involved who are probably hurt, and definitely upset, but removed from us — to something much more personal, intimate even, like making eye contact with a passerby just before they trip and fall on the sidewalk. You aren’t going to die, and neither are they, but you both might want to.

That’s the thing about watching other people fail: we feel uncomfortable because we can imagine how we would feel. Most of us haven’t been major-league pitchers, but we squirm because we’ve all stood bent, with our hands on our knees, over something. The feeling draws us in. We mostly do okay with it. But then something shifts.

The Reliever on the Winning Team Who’s Pissed

I think it is easy to forget, in moments when the win probability of a game has already tipped strongly to one side’s favor, that stakes remain for the individuals on the field. Sometimes it’s wanting to be asked to pitch again the next day; sometimes it’s a matter of pride.

When Shawn Kelley took the mound to pitch the ninth inning of the Nationals’ July 31 tilt against the Mets, the score was 25-1. The Nationals’ win expectancy was 100%. It had been 100% since the seventh. Much like Zac Rosscup, what Kelley did that inning didn’t matter; only it didn’t matter even more. Baseball has never seen a 24-run comeback; since 1908, there have only been 31 games in which a team scored 24 or more runs. Kelley was effectively a winner, and ballplayers love to win. Understood in those terms, Kelley’s sour disposition might strike us as odd.

After giving up a double to Michael Conforto, Kelley looked ready to say some swears.

After jawing a bit with the umpires, who appeared generally displeased with his pace, Kelley appeared quite peeved.

Hey, I’m pitchin’ here!

(Kelley isn’t from New York, but his body language has Dustin Hoffman’s accent from Midnight Cowboy.)

Finally, after Austin Jackson hit a two-run homer, Kelley famously threw his glove in frustration.

At the umpires, maybe, or maybe with his manager for asking him to pitch such a meaningless inning. Or perhaps with God, for adding one more small indignity to a mountain of prior slights, suffered over years and decades.

It was a reaction that seemed outsized to the moment (the Nationals’ subsequent decision to DFA Kelley, who is a useful bullpen piece, seemed similarly disproportionate), but that’s because we’ve understood it within the context of Kelley already being a winner. We thought of it not mattering, without recognizing that it mattered a great deal to him. It wounded his pride. There were stakes; they were just hard to see on the win-expectancy chart.

The Kübler-Ross Model of Pitching

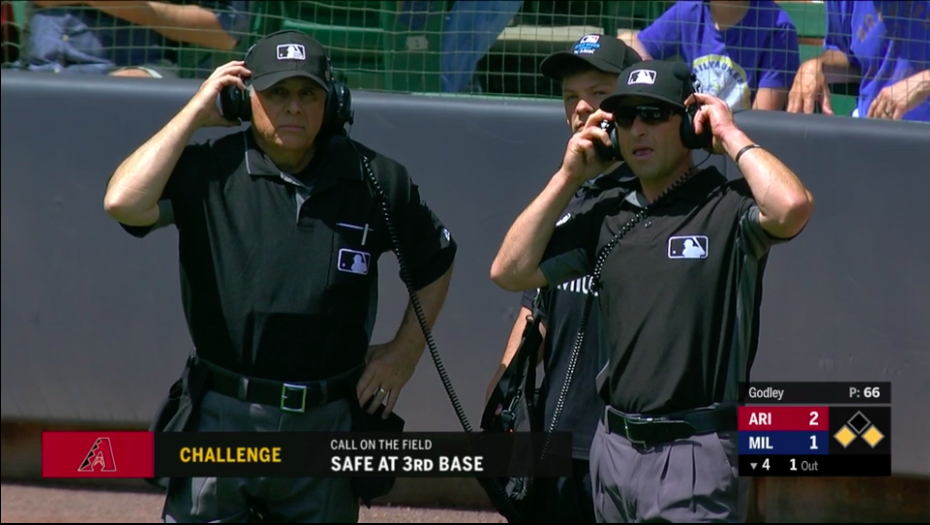

I would imagine the most frustrating type of blowout for a starter is the big inning precipitated by an error. On May 23, Zack Godley took the mound for the Diamondbacks against the Brewers. He was laboring, but he was getting through. Then in the fourth, opposing starter Brent Suter came up to attempt a sacrifice bunt, and this happened.

What followed Paul Goldschmidt’s error — apart from Suter jazz hands and seven runs — was several hundred dollars’ worth of grief counseling, condensed into less than inning.

Denial

Anger

Bargaining

Depression

Acceptance

Good Starter, Bad Bullpen

Baseball broadcasts tell stories, and they rely on characters to do their work. Normally, that’s fine; baseball games are full of characters. But broadcasts can founder when they are suddenly denied previously established protagonists. On May 25, Corey Kluber pitched well enough, holding the Astros scoreless over 6.1 innings. He exited with a 2-0 lead. But then the Indians bullpen blew it. They gave up four runs in the eighth inning and seven more in the ninth. It would have been natural, as his hard work came undone, for the camera to find Kluber in the dugout, but he was nowhere to be seen. He didn’t appear on the home broadcast after the seventh.

One possibility is that the booth wanted to spare Kluber. The more likely explanation, however, is that Kluber simply wasn’t in the dugout anymore. It is hard to be gracious when you’re disappointed, and one mark of maturity — if you know you might be snippy — is to find a quiet corner. I’m sure Corey had hit the showers. But his sudsy time left the broadcast without its leading man, and absent a presumably bereft pitcher, the camera sought out other players.

For instance, in the eighth, the camera settles on A.J. Hinch as he adjusts his undershirt — the sleeves of which he appears to have trimmed up himself — and surveys his handiwork, only to discover that, nope, bad news, still shorter-than-normal sleeves. He seems to feel a bit silly for the fix he’s gotten himself in. Aw, rats.

In the bottom of the ninth, pitching coach Carl Willis checks his watch. Tick tock, still on the clock, pal.

When the game concludes, we meet A Fitness Nut, who’ll take any moment to do some fitness.

But the part that really sticks with us is this kid.

Costumes like this are risky. They depend so much on having happy vibes around you. Maybe when this kid got to the ballpark, he felt tip-top. A little silly, sure — he is a human child dressed like a hot dog — but good. People probably said things like, “Look at that kid! That kid loves hot dogs! Way to go, kid!” Drunk twentysomethings went out of their way to high-five him, which probably made his mother uncomfortable but made him feel super cool.

But things changed in the eighth. What had looked promising for the home team became much less so. The twentysomethings grew quiet. The game now required something different from the crowd, something more grim, something that couldn’t as easily accommodate a child dressed as a hot dog. But what was this kid supposed to do? He’d already made his choice. He was a hot dog! He came dressed for a comedy, only to realize it’s a tragedy halfway through.

Ultimately, it’s a good kid lesson. Tough but good. It’s important to learn that, just because they have a certain food in a place, doesn’t mean you have to dress like that food. You wouldn’t go to a production of Tosca dressed as a glass of overpriced house red, right? Just imagine the looks you’d get when the heroine throws herself off a balcony.

…

There are other ways to get to a blowout. Sometimes a starter just doesn’t have it; sometimes he’s a late scratch and the call-up isn’t equal to the task. But no matter the specifics, they’re all rooted in failure. Extreme failure. Profound failure! There are lessons to be learned in that bit of darkness, but perhaps the most profound one is that, more often than not, players keep going. The Cubs lost big on Tuesday; they took their next two. The only way to do that was to not be destroyed after taking a tumble.

Meg is the editor-in-chief of FanGraphs and the co-host of Effectively Wild. Prior to joining FanGraphs, her work appeared at Baseball Prospectus, Lookout Landing, and Just A Bit Outside. You can follow her on Bluesky @megrowler.fangraphs.com.

I didn’t check to see who the author was before I started reading. But once I got to this paragraph, I knew:

“… but made us look at two whole butts before they did.Butts aren’t what you show when you want to mark an occasion.

Butts aren’t serious. These butts look like walrus faces if you squint. Sorry, butts.”

Don’t ever change, Meg.

Imagine the outrage if a male writer wrote something along these lines about a female athlete.

My god the carnage. Blood everywhere, cops wincing as they step gingerly through the room to avoid touching evidence. A man, lying on the floor, barely hanging onto life. “What happened here, sir?” they ask. He whispers through shallow breaths “It was … the butts.” He should have seen it coming, though. After all how could a man, with all the advantages we have been given throughout our lives, possibly be prepared to deal with a little mild criticism?

“Imagine the outrage if a male writer wrote something along these lines about a female athlete.”

He’d be immediately fired and forced to publicly apologize. The Double Standard strikes again.

If only there were SOMEWHERE on the Internet where you could get your daily quota of discussion about the posteriors of female athletes.

Oh well. What can you do?

The only thing more whiney than whining is whining about whining. Actually that’s not true… what’s even more whiney than that is whining about hypothetical whining, which is what you are doing. In other words, stfu

Jesus Christ dude, grow up. Yes it’s a double standard, but it if you don’t see why it’s a big difference (or the many other double standards that benefit men), I don’t know what to tell you. You not being able to publicly write about female athletes butts is not some great sexist outrage.

I request a MSPAINT.EXE sketch over the butts of how to get my head into walrus pareidolia.