At Long Last, Jorge Soler

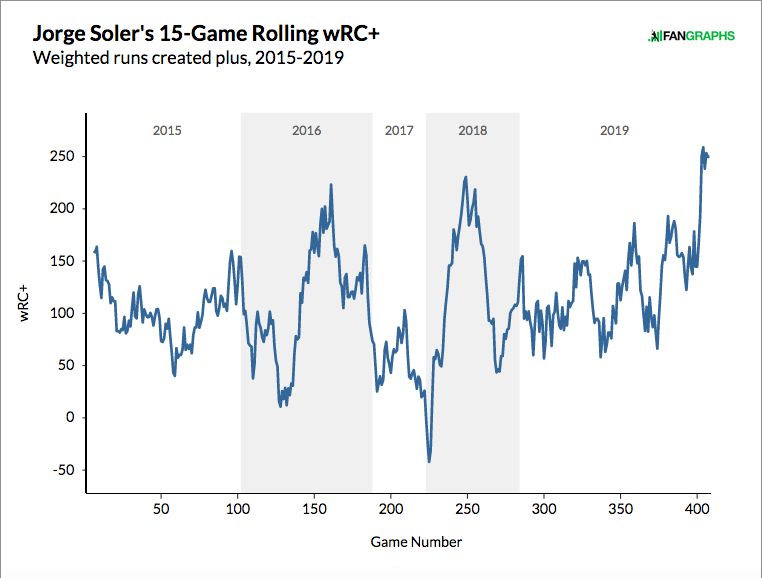

Five years ago, as the Chicago Cubs were playing out the final stretch of their last losing season before their rebuilt roster took flight, they called up two of their top prospects — Javier Báez and Jorge Soler — to get their first look at big league pitching. While Báez struggled, finishing with just a 58 wRC+ and -0.8 WAR, Soler flourished. He burst on the scene with three homers and seven hits in his first three games, and finished his 24-game test run with a .292/.330/.573 line, a 148 wRC+, and 0.7 WAR. Both players figured to be key to Chicago turning the corner, but in the years that followed, the two trended in very different directions.

Báez turned into a defensive wizard and overcame his plate discipline issues with a lethal power stroke, eventually earning a second-place MVP finish in 2018. Soler, however, has failed to live up to the promise he showed in his first season. Thanks to a series of injuries, he was limited to 187 games in the majors between 2015 and 2016, after which the Cubs traded him to the Kansas City Royals. He spent most of 2017 at Triple-A, and posted just a 32 wRC+ in the 35 games he spent in the big leagues. Last year, he began to break out again, but had his season derailed by a broken foot in June. He entered this season having never played more than 109 games in a year, compiling just 1.7 WAR since that debut.

The past few years have been frustrating enough to snuff out the flame of excitement that surrounded Soler’s arrival in the majors, but this season, he’s finally establishing himself as the slugger he was expected to be. After Sunday’s games, he is slashing .259/.351/.549, with a 131 wRC+ and 2.4 WAR. His 35 homers are tied with Ronald Acuña Jr. for fifth-most in baseball, and have him on pace to demolish Mike Moustakas’s franchise record of 38 dingers in a season. They are also nearly triple his previous career-high of 12 homers, set with the Cubs in 2016.

It’s a season Soler has been waiting for his whole career. It was back in 2012 that the Cubs signed the then-20-year-old Cuban defector to a nine-year, $30-million contract. That was the same year that high-profile Cuban signees Yasiel Puig and Yoenis Céspedes made their stateside pro debuts, and Soler drew some comps to both. He was 6-foot-2 and somewhere between 205 and 225 pounds, and had a quick right-handed swing that produced towering home runs. With sharp pitch recognition skills that allowed him to draw walks and a steady clip, his ceiling seemed to be as high as anyone’s in the Cubs’ burgeoning farm system.

He was impressive in a 34-game debut in the low minors in 2012, but almost immediately, injuries began to hinder what could have been a fast rise through the Cubs organization. He was limited to 55 games in 2013 because of a stress fracture in his tibia, and he missed more time with a hamstring strain in 2014. The latter of those injuries didn’t stop Soler from soaring through three levels of the minors en route to a big league promotion later in the year, but the pattern of health problems was only beginning.

In 2015, Soler missed a month with an ankle injury, then about three more weeks later in the year due to an oblique injury. He missed two months of 2016 after injuring his hamstring again, and then missed a month of 2017 with another oblique issue. With the aforementioned broken foot costing him three and a half months of 2018, Soler wrapped up his fifth year of playing in the majors having appeared in just 307 big league games.

That has made 2019 a special season for Soler in ways not limited to his performance. His 125 games played this season are not only the most he’s ever played in a season, but also tied for the most games played by anybody in the majors this year. For the first time in his career — and please, for goodness sakes, knock on wood if it’s available to you — Soler has been healthy and available for every game the Royals have played. That’s a conclusive success for the slugger, and the consistency in playing time he’s finally achieving seems to be having very positive effects. If a player isn’t used to playing this many games in a season, it seems reasonable to expect he might exhibit fatigue as the year goes on, and see his play suffer as a result. For Soler, the opposite is taking place.

Soler has gone through the peaks and valleys most players tend to experience over the course of a season, but overall, his production has trended upward the longer he’s played. That improvement has reached a crescendo in August, as Soler has turned in the hottest stretch of his career:

| Category | Value | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| BA | .378 | 11th |

| OBP | .533 | 2nd |

| SLG | .911 | 2nd |

| BB% | 21% | 3rd |

| wRC+ | 259 | 2nd |

| WAR | 1.30 | 6th |

Is that a small sample fluke? It could be. Soler is built for home runs, and the modern game is too. Someone like Soler clustering seven homers in a 15-game span shouldn’t be all that surprising in 2019. But to me, this isn’t just a story of a power hitter finally staying healthy enough to post a big home run total in the most dinger-happy season in history. This is a story of someone getting 500 plate appearances for the first time in his career, and because of that, locking in more and more each game:

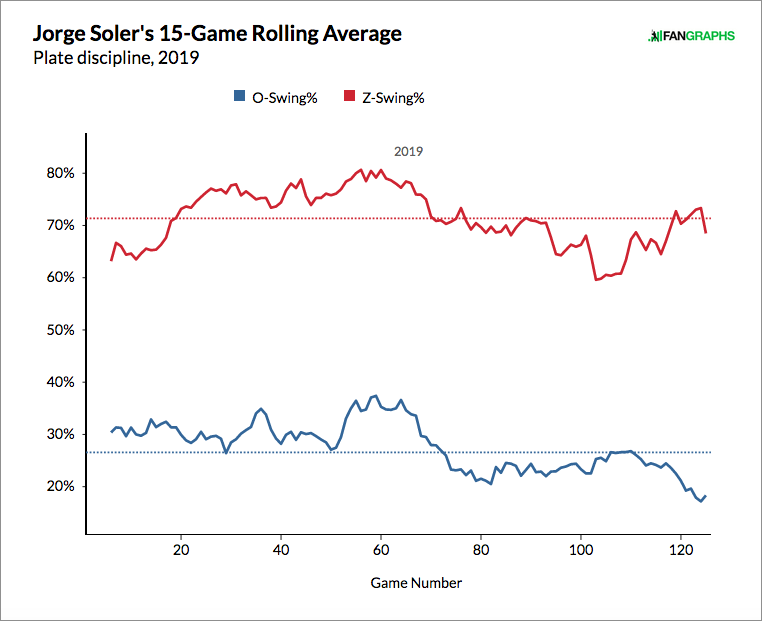

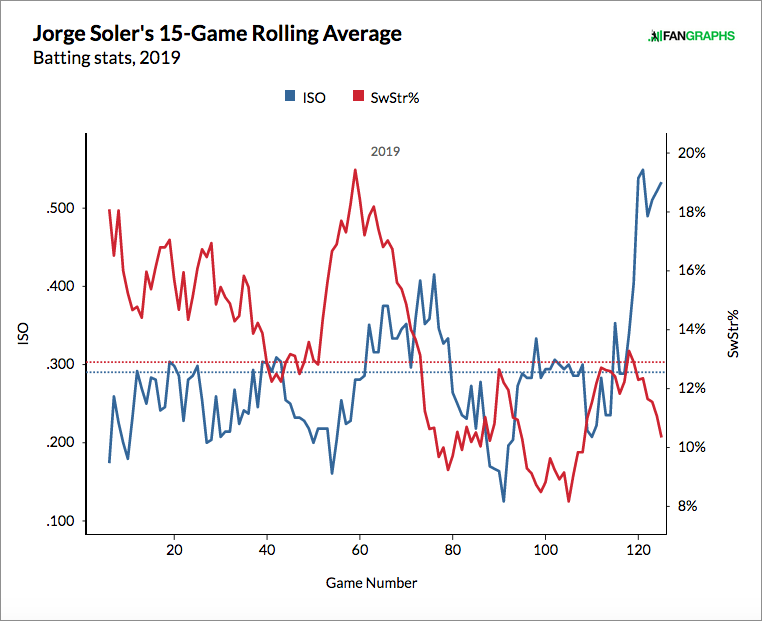

There’s a compelling story here. While fighting through ailments in limited spurts of big league action, Soler has traditionally swung at about a league average percentage of pitches both inside and outside the strike zone, and has whiffed at a rate that is well above average. Near the end of May, he became a very aggressive swinger, and his performance suffered for it. But as the year has gone on, and he’s seen more pitching, he’s developed an increasingly sharp sense of when he should be swinging, and what he shouldn’t be. As he’s gone on his recent tear, he’s continued to swing at about the same number of pitches in the strike zone as he always has. But his chase rate has plummeted, and aside from one spike, has fallen rather precipitously as the season has gone on. His swinging strike rate has also tapered off noticeably, while his ISO has gradually risen until reaching a previously unseen height.

Baseball is game of repetition. In order to hit advanced pitching, a player typically needs to see a lot of it, and for an extended period of time. For the entirety of his career prior to this season, Soler hasn’t gotten that opportunity. He’s missed considerable time with injuries, and with all of those injuries, it’s probably fair to assume he wasn’t at 100 percent for many of the games he actually did play. It takes time to build up the vision and reflexes necessary for a hitter to attack the right pitches with conviction, and pass on pitches he knows he can’t punish.

That’s what Soler is doing now, and it’s resulted in him looking like the hitter he was forecast to be years ago. Statcast has him in the 94th percentile in xwOBA, the 95th percentile in average exit velocity, and 97th percentile in xSLG. He’s become something close to elite. Soon, he’ll have his name in Royals record books. And if he stays healthy, he might just be getting started.

Tony is a contributor for FanGraphs. He began writing for Red Reporter in 2016, and has also covered prep sports for the Times West Virginian and college sports for Ohio University's The Post. He can be found on Twitter at @_TonyWolfe_.

Is he really that terrible with the glove?

::also wonders why the WAR isn’t higher, looks him up, has eyes bulge out of head like looney tunes character when viewing def stats::

Looks like a disagreement between numbers between sites though, so…?

Makes me think about something Jaffe said recently about UZR not accounting for shifts…

Generally, DRS tends to spew out more extreme results than UZR.

That in itself is not inherently good or bad but it does lead me to regressing DRS more heavily when trying to evaluate a player’s true defensive talent.

By the eye test, he seems to take some interesting routes to fly balls.