Dinelson Lamet Throws Two Sliders Now

We treat the statistics around torn UCL’s and Tommy John surgery with abstract sadness. It’s awful that so many elbows blow out, but for the most part, it’s just a number. Sure, when a star is injured, we notice — Jordan Hicks, say, or Shohei Ohtani. Those are marquee names, and the disappointment over not getting to see them pitch is merited. But that doesn’t mean that other players who need surgery aren’t just as sad of a story.

Consider Dinelson Lamet. When he made it to the majors in 2017, he was a rare bright spot for the Padres. Three years after signing with them as an international free agent, he’d torn through the minors, striking out 27% of the batters he faced at a mix of levels he was too old (rookie ball at 22) and too young (Triple-A at 24) for. Without much reason to keep him in the minors, the Padres called him up.

Lamet wasn’t a star. He didn’t feature on Twitter highlights, wasn’t gunning for any records. His wasn’t a story to set the major leagues ablaze, the heralded Padre savior arriving to lead the team to the playoffs. That doesn’t mean he wasn’t effective, though; it doesn’t mean that he wasn’t a great story.

Even as he tore through the minors, Lamet looked like a reliever before he got to the majors, with only two pitches he had confidence in. After throwing just two starts in Triple-A before 2017, he was an average pitcher over 114 innings with the big league club. The two-pitch arsenal played — his slider was good enough to offset the lack of a third pitch. A ZiPS darling from day one, he was living his major league fantasy — the Padres slotted him in as their number two starter for 2018.

And just like that, he was gone. He felt pain in his elbow while making his final start of the spring, and a few MRIs later, he went under the knife. If you weren’t a Padres fan or a fantasy baseball owner, though, you might never have known. Lamet was a long shot to make it from the start, and even though he’d defied the odds for a season, the abyss is never far away for a major league pitcher.

Lamet has always lived on the margins as a starter. Two-pitch pitchers have a tough time starting, and Lamet was no exception in his 2017 debut. The problem is two-fold — opposite-handed batters are tough to beat without a pitch that breaks away from them, and facing the same batter multiple times without a new look to show is dangerous. Lamet had particular trouble the third time through the order, but he suffered nearly as much against lefties:

| Split | TBF | K% | BB% | wOBA | FIP | xFIP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vs. L | 253 | 24.1% | 13.8% | .364 | 5.23 | 5.04 |

| vs. R | 232 | 33.6% | 8.2% | .239 | 3.50 | 3.39 |

| 1st Time Thru | 189 | 34.9% | 10.1% | .261 | 3.68 | 3.64 |

| 2nd Time Thru | 189 | 28.0% | 12.2% | .287 | 3.92 | 4.02 |

| 3rd Time Thru | 105 | 19.1% | 11.4% | .410 | 6.77 | 5.78 |

For the most part, there’s only one solution: throw another pitch. More looks are always better, and if you can add a changeup, you can use it extensively against opposite-handed batters, as it will break away from them. That’s not the only method, though, merely the easiest. Clayton Kershaw, to name one famous example, never developed a changeup — his curve and slider are simply good enough that it doesn’t matter. That’s not a perfect example, as Kershaw still uses three pitches, but it’s a sign that you can beat same-handed batters without a changeup.

Without Kershaw’s freakish talent, Lamet has blended his approach with that of another Dodger. Rich Hill is the quintessential two-pitch pitcher: he has his signature curveball and a fastball with tremendous rise. He’s thrown those two pitches more than 90% of the time in his career, and more than half of the remaining 10% of pitches look like mis-classified curveballs. Despite that limitation, he has a negative platoon split over nearly 4000 career batters faced. In fact, his strikeout rate is higher against right-handers than lefties. How does he do it? He throws several pitches that all get classified as curveballs, and the pitches have different roles.

When Lamet was injured in his final Cactus League start, he was working on a curveball to pair with his slider. It started out as a slow, bendy pitch, but as he told Dennis Lin through an interpreter, “I can throw the curveball a little harder, and that makes it blend into the slider. If I do speed up that curveball, then it ends up changing shape in terms of high to low and side to side.”

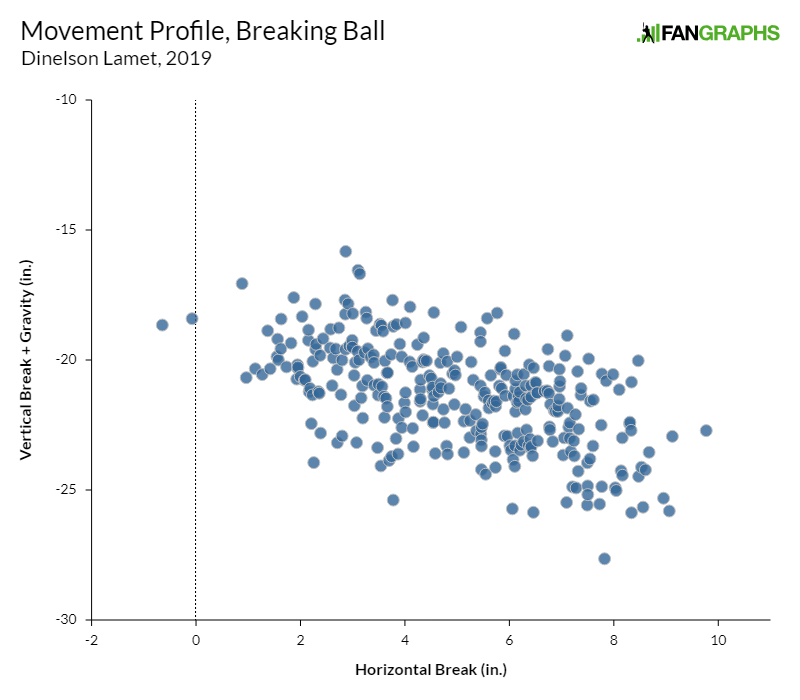

That, it appears, is just what Lamet has done this year. His slider used to be a consistent pitch, a sideways-breaking pitch that he threw with a similar break basically every time. This year, though, he’s messing around with it, altering its break significantly. Using Alan Nathan’s research, I was able to produce horizontal and vertical breaks for every individual pitch thrown this season. Take a look at every breaking ball Lamet has thrown, graphed by horizontal break and vertical break inclusive of gravity:

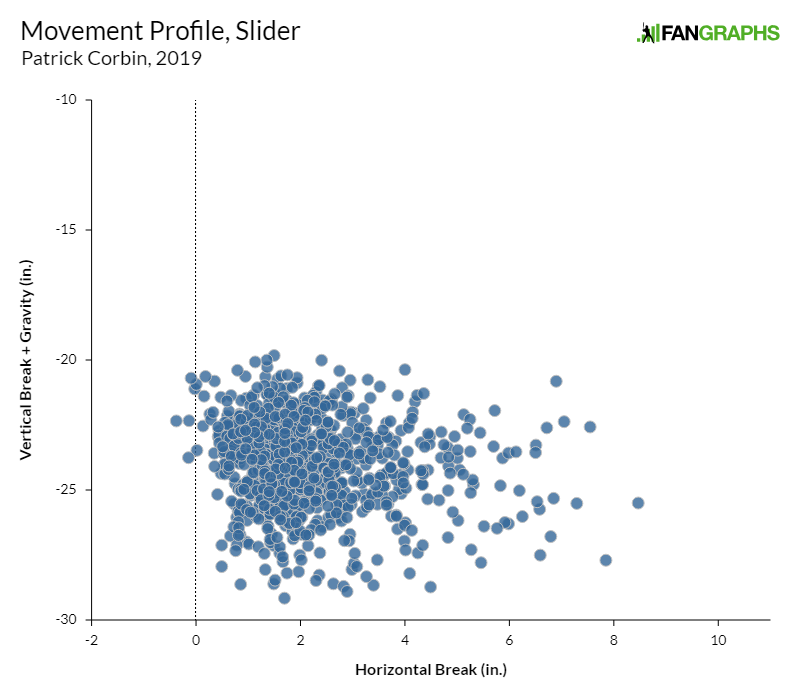

That might not look shocking to you at first glance, but that’s mostly not how pitches work. If a pitcher repeats his mechanics, you tend to see a cluster of pitches with similar break. Take a look at slider master Patrick Corbin’s sliders this year:

Unfortunately, we can’t compare 2019 Lamet to 2017 Lamet, because in 2017 Statcast was in its first year of replacing PITCHf/x, leading to calibration issues that were at times severe. Still, it’s plain to see that Lamet is changing up his sliders significantly. Think of it this way: 50% of Corbin’s sliders break between 1.3 and 2.7 inches to his glove side. That 1.4-inch range is Corbin executing the same pitch over and over again.

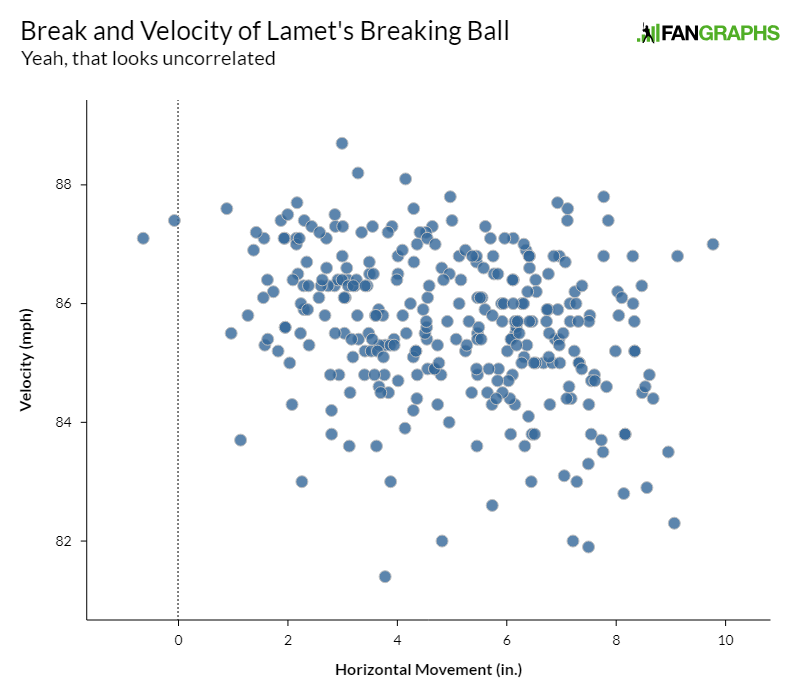

In contrast, 50% of Lamet’s pitches move between 3.4 and 6.5 inches to the glove side, a range more than twice as wide. It’s hard to find the center of Lamet’s distribution, because he’s throwing essentially two different pitches — a heavy-breaking, downward-tilted slider, and one that breaks much less and actually rises relative to gravity, more of a cutter. Every pitch is somewhere between those two extremes. Lest you think that’s all an artifact of throwing the ball harder or softer, take a look at the speed of each pitch compared to the horizontal movement:

What this means is that in practice, he’s turned one good slider into one big slider with break and a tight, cutter-ish one. They happen to go roughly the same speed and have roughly the same spin, but he’s already thrown 10 pairs of back-to-back breaking balls whose horizontal movement differs by more than 4.5 inches. Corbin, by contrast, has thrown just six, despite throwing three times as many breaking balls.

What about the results? Lamet has looked better in every split this year:

| Split | TBF | K% | BB% | wOBA | FIP | xFIP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vs. L | 85 | 27.1% | 7.1% | .328 | 3.43 | 3.74 |

| vs. R | 91 | 35.2% | 12.1% | .282 | 4.17 | 3.81 |

| 1st Time Thru | 72 | 31.9% | 15.3% | .343 | 4.26 | 4.26 |

| 2nd Time Thru | 71 | 33.8% | 7.0% | .245 | 2.83 | 3.27 |

| 3rd Time Thru | 33 | 24.2% | 3.0% | .349 | 5.31 | 4.00 |

None of these are terribly large samples, of course; 85 plate appearances isn’t enough to believe that a 3% strikeout rate increase and 6.7% walk rate decrease will stick. The third time through the order is even skinnier, and the team would be well suited to avoid using Lamet a third time through too often, even with his improvement.

This got me wondering: is this a good plan? It certainly seems intentional — Lamet specifically mentioned that he was going to try to throw the curve like the slider. It hasn’t really hurt his control — my favorite split to look at breaking ball control is zone rate when behind in the count, and Lamet has hardly slipped, from 49% pre-surgery to 46% now. That’s not enough to mean anything, and even if it were, the rust of missing a year is a more likely culprit.

If anything, the pitch has gotten better at missing bats. Lamet is running a spicy 52.7% whiff-per-swing rate, top 10 in all of baseball among breaking pitches. A lot of this is because he’s missing less when ahead — he left breaking balls over the heart of the plate more than 20% of the time when ahead in the count in 2017, and he’s gotten that down to 15.5% in 2019. The pitch has allowed harder contact this year, but we’re still squarely in small sample territory there.

For the most part, the one-slider-as-two-pitches gambit has worked. Pitch tracking systems can’t categorize it, but there’s no denying its effectiveness so far — if he’d pitched enough innings to qualify, he’d be behind only Justin Verlander and Max Scherzer in run value per pitch. It doesn’t hurt, of course, that his fastball has averaged an eye-popping 95.8 mph, good for a starter even in today’s velocity-obsessed game. He’s even mixing in a heretofore-missing changeup from time to time — Eric Longenhagen captured all three pitches in slow motion during Lamet’s rehab start:

All this has added up to a successful return season — Lamet has a 3.95 ERA to go with a 3.83 FIP and 3.78 xFIP, and he’s striking out 31.3% of the batters he faces as compared to only 9.7% walks. Each of those five numbers is an improvement on his already-acceptable 2017. The strikeout rate, in particular, is spectacular — it would be seventh in baseball if he had enough innings to qualify.

All of this data and speculation is a long way of saying that Dinelson Lamet is back. He didn’t have to be — something like 20% of players who tear their UCL never pitch in the majors again. He’s good, too, which was certainly no guarantee — pitchers flame out all the time. Will it last? Will his multi-look slider stay one step ahead of the competition? It’s too soon to tell, but the fact that it’s even a question is wonderful.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Interesting to note the classification of his repertoire between FanGraphs and Savant.

Depending on which FG source you look at, he’s throwing a slider 40.7% or 45.1% of the time, with the addition of 4.5% curveballs on the former.

Switch to Savant and they have him at 32.6% curveballs and 12.5% sliders on the season.

Still adds up to about the same amount, but it’s interesting to see the classifications of pitches by different systems. If anything, this just reinforces that he’s made a conscious choice to throw the pitch differently.

And Brooks has him as all sliders! It’s a great example of how hard breaking balls are to categorize. Nick Anderson is similar; he throws a breaking ball that is too hard to be a curve but too vertical to be a slider, and so systems disagree.

As someone who can never remember what pitch names actually correspond to (i.e. which pitches break glove-side vs arm-side, which pitches have more horizontal break vs vertical break, etc), it would be cool if there was a glossary piece or maybe even a full-blown article that associates each pitch type (fastball/sinker/cutter/change-up/slider/splitter) with its average movement, velocity, and spin characteristics in any given season (or across multiple seasons of pitch-tracking data). As Ben points out, to some extent the classifications are arbitrary (and are also based on less quantifiable things like grips), but it would be cool to have a reference guide.