Trevor Cahill, Marco Gonzales, and David Phelps on Crafting Their Curveballs

Pitchers learn and develop different pitches, and they do so at varying stages of their lives. It might be a curveball in high school, a cutter in college, or a changeup in A-ball. Sometimes the addition or refinement is a natural progression — graduating from Pitching 101 to advanced course work — and often it’s a matter of necessity. In order to get hitters out as the quality of competition improves, a pitcher needs to optimize his repertoire.

In this installment of the series, we’ll hear from three pitchers — Trevor Cahill, Marco Gonzales, and David Phelps— on how they learned and developed their curveballs.

———

Trevor Cahill, Los Angeles Angels

“I didn’t throw my [current] curveball until my second year in the big leagues. I used to throw the double-knuckle — I didn’t spin it; I would literally flick it — and that worked in the minor leagues. It was actually my strikeout pitch. But once I got up here, I couldn’t really throw it with the big-league ball. Not consistently.

“The seams in the minor leagues were bigger, and that made a difference. Plus, big league hitters are more patient. I used to throw that pitch in the dirt a lot, and get swings, but I had trouble throwing it for strikes. Big league hitters, if you can’t throw it for a strike, they see that spin and just spit on it.

“One day I was playing catch with Brett Anderson, working on his slider grip, which he spikes. I did that, and it was really good on flat ground, so that offseason I started working on it. Then my finger started coming up higher, so I was throwing a normal spiked curveball. In 2010, in spring training, I started using it against hitters. I’ve thrown it ever since.

“Now that they have all the numbers they give us… I started throwing it more when I went to San Diego. They were like, ‘Hey, you’ve got good spin on it, so you should be throwing it more.’ I’ve gotten it up to 3,000 [rpm], and I think I’m usually around 2,900. So in any big situation, I’m probably going to go with it.”

Marco Gonzales, Seattle Mariners

“My original curveball came from my pops. My pops was a professional left-handed pitcher as well, and he was the one who first put it into my hand. This is when I was around 12 or 13 years old. But growing up in Colorado… that’s a big changeup world. The curveball is a hard pitch to learn there, so for me the curveball didn’t really come to fruition until college.

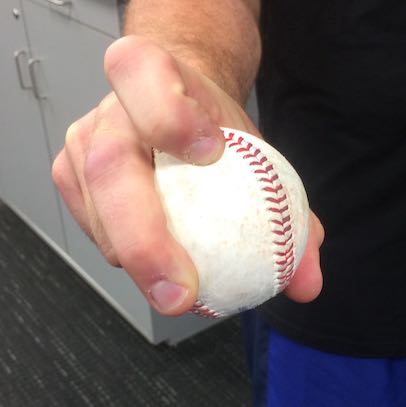

“I played college ball up in Washington, at Gonzaga, and that’s where I really started to have more drop on it, more spin, and I got a better feel for it. I also started to spike it; I started putting my index finger into the baseball — the tip of my finger — instead of putting it flat.

“I felt that having my index finger on the ball gave me less pressure, and less efficiency. When I put the tip of my index finger on the baseball, it actually sinks the ball deeper in my hand, and I’m able to get a stronger grip with my middle finger. When I started putting more focus on my middle finger is when it started getting better.

“My first year of pro ball, going into instructs… not a ton changed then. I just focused more on placement, and usage, in games. Truthfully, my best curveball is probably the one I have now. That’s come post-Tommy John surgery. My grip strength has gotten a lot better, and my arm is a lot stronger. I feel that’s helped tighten it up and make it a lot sharper pitch.

“I think a good curveball comes with increased grip strength and learning to maneuver the baseball a little bit. Grip strength is important. You’re out there throwing 90 to 100 pitches, and a lot of that is finger pressure, which is very taxing. In order to throw hard, and with a lot of spin, you need to have a good amount of finger strength and grip strength.

“In the gym, and in my spare time during the offseason, those are things I train. Squeezing. Doing a rice bowl — squeezing and clenching a bucket of rice — and just in general, carrying heavy things. I put a lot of focus on things that affect pitching.”

David Phelps, Chicago Cubs

“I was coming off a really good year, in 2016, and not having the success I wanted to have. I was throwing a majority of fastballs and cutters — two of my better pitches — and AJ Ellis sat me down and said, ‘Dude, you’re showing them everything hard; you can buy a lot of free strikes early in the count with your breaking ball, then get them out hard.’ Then he ran me through a couple guys, showing me their hot and cold zones and what they do in certain counts. He more or less said there are a lot of free strikes out there, and that I had the ability to just dump my curveball in there for strikes.

“As the idea of tunneling pitches has gotten more and more popular, we talked about how the four-seam up in the zone plays off the breaking ball when I throw it for a strike. That conversation was right around the end of April in 2017. Soon after that, I went on one of the better runs of my career. If you were to go back and look at a lot of the sequences I worked to lefties, a lot of it was 0-0 breaking balls for strikes.

“Going back [to first learning it], I didn’t start throwing a curveball until I was somewhere between 16 and 18. I didn’t pitch a ton when I was little. I’ve always had the ability to throw hard — obviously, most everyone in this game who is a pitcher had that same ability; it’s kind of why we’re here — but I didn’t really start throwing a curveball extensively until I got to college.

“I took pitching lessons when I was in high school, but coming out of high school I was more of a slider guy. Once I got to [Notre Dame] and started working with my pitching coaches — freshman year it was Terry Rooney, and Sherard Clinkscales after that — it became a good pitch for me to keep hitters off of my harder stuff a little bit.

“When I first came up, in 2012, I was throwing 90-92 and my curveball was predominantly my out-pitch. I was having guys chasing it, down. And it’s funny, because in the minor leagues, I wasn’t [curveball-heavy]; I was two-seam/slider/cutter. Then I got to the big leagues and Russell Martin had confidence in my curveball. The more and more he called it, the more confident I got. We had good results with it.

“Then I got away from throwing it. I’m not sure why. I don’t know if it was my mechanics getting off a little bit, trying to do too much with it, or what. I mean, I still threw it, but I kind of fell in love with my cutter too much. I was a young kid trying to survive at the big league level, so I was relying on the two pitches I had the best feel for, the fastball and the cutter.

“When I started throwing it again, in 2017, the biggest difference was that my stuff had ticked up. I started throwing harder. With more arm speed, and more hand speed, I was able to spin my curveball a little better. The break was pretty similar, but I went from throwing it 76-78 [mph] to up around 82-83. It became more of a power pitch.”

——

The 2018 installments of this series can be found here.

David Laurila grew up in Michigan's Upper Peninsula and now writes about baseball from his home in Cambridge, Mass. He authored the Prospectus Q&A series at Baseball Prospectus from December 2006-May 2011 before being claimed off waivers by FanGraphs. He can be followed on Twitter @DavidLaurilaQA.