Author Archive

Strategic Slip in Seventh Stunts ‘Stros

When the seventh inning began, the Astros’ chances of winning the World Series looked good. With a rolling Zack Greinke, Gerrit Cole available out of the bullpen, and closer Roberto Osuna fresh, the Astros had a clear path to getting the final nine outs and celebrating a title for the second time in three seasons. It didn’t work out that way. The Nationals rallied, the Astros were defeated, and A.J. Hinch’s decision making merits some scrutiny. Bad outcomes can cause us to believe the decisions that led to those outcomes were poor, when that isn’t always the case. Let’s take a look.

We’ll start with Greinke entering the seventh, take a quick detour, and then get back to him. After six innings, Greinke had made a total of 67 pitches; he got through the sixth on just eight pitches, including a strikeout of Trea Turner to end that frame. While Greinke’s velocity is not a big part of his game, his fastball velocity was still fine and he topped 90 mph on one of the pitches to Turner. Heading into the seventh, Astros manager A.J. Hinch had a few different options. He could continue on with Greinke, go to Cole, go to Osuna, or go to someone else, like Will Harris or Jose Urquidy.

There are two causes for concern with respect to Greinke, one sort of real, the other self-imposed by the Astros. The Greinke-related issue is that he was about to face the Nationals the third time through the order. He had retired Turner, but Adam Eaton, Anthony Rendon, and Juan Soto loomed. But at this point in the game, facing the order a third time should have been of minimal concern. The “penalty” pitchers often experience is due to two factors. One is the rising pitch count of the pitcher. With Greinke only at 67 pitches, that really wasn’t an issue. The other factor is that the third time through, pitchers often pitch against a portion of the lineup that is disproportionately comprised of the better hitters at the top of the order. While that was an issue for Greinke with Eaton, Rendon, and Soto, it would have been a problem for the Astros no matter who was on the mound. So then the question is, who is the better pitcher, a rolling Zack Greinke or one of the bullpen arms?

Will Harris as reliever and Zack Greinke as starter put up roughly equivalent numbers, with FIPs around three. Add to that that Harris had pitched the night before and Greinke seems like he was a sound choice. Urquidy pitched well in the fourth game of the series and also performed well in two relief outings earlier in the postseason. There’s an argument to be made that as a reliever, Urquidy might be a little better than Greinke as a starter, but it isn’t an especially compelling one. Roberto Osuna also put up similar numbers to Greinke’s in the regular season. The idea behind pulling starters is to replace them with relievers who are better. Greinke at 67 pitches is one of the 10 best starters in baseball, and as good or better than most of Houston’s relief options. It doesn’t make a ton of sense to pull him while he’s still on his game.

That leaves Gerrit Cole. It’s not clear why Cole was only going to be available for the ninth inning if Houston got the lead. He was warming earlier in the game. He was pitching on two days rest, so it’s possible he was only going to be available for an inning, and it seems reasonable to want to put him in at the start of an inning so he can be better prepared for it, but having him only available in the ninth to close out a World Series win is an odd choice and makes one wonder if the decision wasn’t entirely baseball-related. In any event, if Cole could have only gone one inning and needed to start it, then sticking with Greinke to start the seventh was completely reasonable.

Here’s where Greinke’s pitches went to the first three batters in that frame, from Baseball Savant.

Against Eaton, he pounded the outside corner away and induced a groundout. Against Rendon, Greinke threw the hardest pitch of his night at 91.8 mph for a ball, and then missed with a changeup that Rendon crushed. The walk to Soto put the winning run on base, but Greinke caught a bit of a bad break during the at-bat. After a 1-0 whiff on an outside curve, Soto took a change outside. Then, he took a change that should have made the count 2-2, but instead made it 3-1. With the count tilted in Soto’s favor, Greinke threw the same curve that got the whiff earlier, but Soto took the pitch and went to first.

With Howie Kendrick coming up, we are faced with a set of questions similar to those from the beginning of the inning. Greinke was now at 80 pitches and with a walk and a homer, the results said he was getting worse. His velocity against Rendon and the tough break against Soto — one of the best hitters in the game regardless of age, with his 155 wRC+ against righties behind only Christian Yelich, Mike Trout, Cody Bellinger, and George Springer (min. 350 PA v RH) this season — it’s not clear that Greinke didn’t do the right thing by not giving in. Cole seemingly needed a clean start to the inning to enter the game, and that logic might have also been true for Urquidy, who had only come in during the middle of an inning with the Astros once. (That relief outing came in the second inning of a September game against the Angels, and while barely worth mentioning, he gave up a single to the first batter.)

In his piece on the same subject, Michael Baumann discussed the reasons why relieving Greinke and bringing in Harris was defensible, though he did acknowledge Harris’ potential wear as a point against it. That Osuna came in later that inning is another point against it (Osuna is better than Harris), but it’s still not clear that pulling Greinke was the right move. With the lineup through Rendon and Soto, unless Greinke was tired, any issues related to the third time through the order were mostly moot. Howie Kendrick has been a good hitter, but he’s not on the level of Rendon or Soto. With Kendrick and then Asdrúbal Cabrera coming up, leaving Greinke in might have been the best play if Hinch was going to bring in a pitcher other than Gerrit Cole or the best reliever. And if Greinke was tiring, he wasn’t really showing it based on velocity and just pitching Soto carefully.

At that point, the decision should have been Osuna or Greinke; if Hinch thought Osuna wasn’t the best available reliever because he had a few slip-ups in the postseason, then the choice should have been sticking with Greinke. Playing by the numbers doesn’t always require pulling the starter. Relievers aren’t necessarily better than the guy currently on the mound, and even good relievers aren’t usually better than a fresh starter if he’s one of the 10 best in the game. Greinke might have had some so-so outings in the playoffs before last night, and his three strikeouts might not have suggested dominance, but 19 called strikes out of the 80 pitches he threw is an indicator that he was keeping Washington off balance. Was relieving Greinke defensible? Sure. Was it the right call? I’m less certain. It’s usually better to take a pitcher out too early than too late, but in the most important plate appearance of the season, Houston’s fifth-best pitcher threw the pitch that lost the Astros the lead and eventually the championship.

A Dumb Rule Almost Ruined the World Series

The Nationals won last night thanks to a great outing from Stephen Strasburg and a big home run from Anthony Rendon in the seventh inning. But just before Rendon’s homer, this play happened, per our Play Log:

Trea Turner grounded out to pitcher.

That description is a little lacking. How about this:

Turner was called out for interference. Dave Martinez got mad at the umpires. Trea Turner got mad that Joe Torre wasn’t doing anything. There was a delay, and at its end, Turner was still out. Rendon hit a homer that reminded everyone of Rasheed Wallace and the Nationals forced a Game 7, but the play and the rule deserve some scrutiny.

We should first address the rule we are talking about. Turner’s offense was not your standard interference call under Rule 6, as that type of interference requires intent like on this rather famous play:

Stephen Strasburg is a Postseason God

In 2012, Stephen Strasburg didn’t pitch for Washington in the postseason after being shut down due to injury concerns. He did make his playoff debut in 2014, and in one start gave up two runs in five innings while striking out just two with a walk and a hit-by-pitch. It wasn’t a great start to his postseason career, but since that outing, Strasburg has been incredible. He made two starts against the Cubs in the NLDS in 2017. He went seven innings in the first one, striking out 10 and walking just one while giving up two unearned runs in a loss. In an elimination game later that series, Strasburg again went seven innings, this time striking out 12 against two walk and no runs in a Nationals victory. That 2017 NLDS gave everyone a taste of what Strasburg could do in the playoffs, and this year, he’s putting together one of the greatest postseason runs of all time with a chance to keep the Nationals title hopes alive tonight.

Strasburg first appeared this postseason in a season-saving relief outing in the Wild Card game in which his three shutout innings kept Washington within range before the offense could make a comeback and advance to the NLDS. Against the Dodgers in the next round, he struck out 10 batters in six innings with no walks and just one run to keep the Nationals from going down 0-2 in the five-game series. Then, in his only blip of the postseason, Strasburg gave up three runs in the first two innings of the deciding game against the Dodgers, but he allowed no runs over the next four as the Nationals won in 10 innings. He shut down the Cardinals with 12 strikeouts and no walks in seven innings in the third contest of a four-game NLCS sweep. Finally, in the second game of the World Series, Strasburg outdueled Justin Verlander and threw 114 pitches in six difficult innings to hold the Astros to two runs. Read the rest of this entry »

Neither the Problem Nor the Solution in Pittsburgh, Pirates Fire Neal Huntington

Some change is coming to the Pittsburgh Pirates. Over the last month, the team has fired long-time manager Clint Hurdle and President Frank Coonelly, and today the news came out that GM Neal Huntington is out of a job as well. Owner Bob Nutting is still the one making the calls in Pittsburgh, but the team has hired a new President, with former Pittsburgh Penguins hockey executive Travis Williams taking over the business side of the operation in hopes of duplicating his success with the city’s hockey team. As for Huntington, his departure signals a major change in operations for the Pirates. But a change in operations doesn’t necessarily mean a change in direction, and some skepticism regarding the latter is warranted given the last few decades of Pirates baseball.

Every franchise experiences inflection points, where the team charts a new course in an attempt to move forward. The Boston Red Sox won the World Series in 2018; a year later, they fired Dave Dombrowski and brought in Chaim Bloom to help sustain his predecessor’s success while avoiding the failings that precipitated Dombrowski’s departure from Detroit. After sustained failure, the Cubs hired Theo Epstein and the Astros brought in Jeff Luhnow. Both were enlisted to tear down and then rebuild their respective franchises in the hopes of striking out on a new path and contending for the playoffs and championships. It’s not entirely clear that this is what’s happening in Pittsburgh. The club missed its opportunity to capitalize on its three-year playoff run from 2013 to ’15, and faces a future that doesn’t look too different from most of its past. Read the rest of this entry »

Astros Take Game 3 from Aníbal Sánchez and the Nationals 4-1

In a technical sense, Game 3 wasn’t a must-win for the Astros. In a practical sense, the odds of Houston winning four straight games against the Nationals are under 10%. The Astros needed the win, and they got it with a 4-1 victory. For those purists of the game who enjoy pitchers batting, Game 3 of the World Series highlighted one of the big differences in strategy between the American and National Leagues: pitchers as hitters.

Greinke’s Bunt

The first potentially important pitcher plate appearance occurred in the top of the second inning. Zack Greinke came to bat with one out and runners on first and third. Greinke’s season wRC+ of 123 doesn’t really represent his true hitting talent, but his career 60 wRC+ also understates his value in this situation. Greinke got down a successful bunt and advanced the runner to second, but the Astros’ win expectancy went down about five percentage points. If Greinke had done nothing, it would have only gone down a single percentage point more. While a double play would have dropped the win expectancy by about 10 percentage points, a sac fly would have moved the Astros up four percentage points, while a single would have moved them up six.

Greinke’s career wRC+ indicates he isn’t a particularly good hitter, but it’s mostly due to his inability to walk or hit for power. With a .225 lifetime average, he hits a decent number of singles, which is what the Astros needed in this situation. With a runner already on third, moving a single runner to second doesn’t help much when there are two outs. The expected situation is a Greinke out, which drops win expectancy by six. The bunt is only one percentage point so we’re really dealing with the chances of a double play versus the chances of a single. Given the large bump from a single compared to the expected out, versus the small drop from the bunt to a double play, the double play would have to have been much more likely than the single to make bunting the right choice. That isn’t in the case here, particularly with Aníbal Sánchez giving up a bunch of loud contact in the first few innings. George Springer followed the bunt with a groundball out to keep the game at a one-run deficit for the Nationals. Read the rest of this entry »

Juan Soto Does the Impossible

In Game 1 of the World Series, Juan Soto hit an opposite-field home run off a high 96-mph fastball from Gerrit Cole all the way to the tracks of Minute Maid Park. Those conditions together shouldn’t even be possible. Fortunately, unlike aurora borealis at noon in May in the middle of the country localized entirely in Principal Skinner’s kitchen, you can actually see it.

Here’s the pitch and the swing.

Here’s where the ball went:

Here’s where it landed:

There have been about 30,000 homers hit between the regular season and postseason over the last five years, and we don’t need to stretch things too much to say that there hasn’t been a homer like this one during that time, even without accounting for the fact that this happened on the game’s biggest stage. Read the rest of this entry »

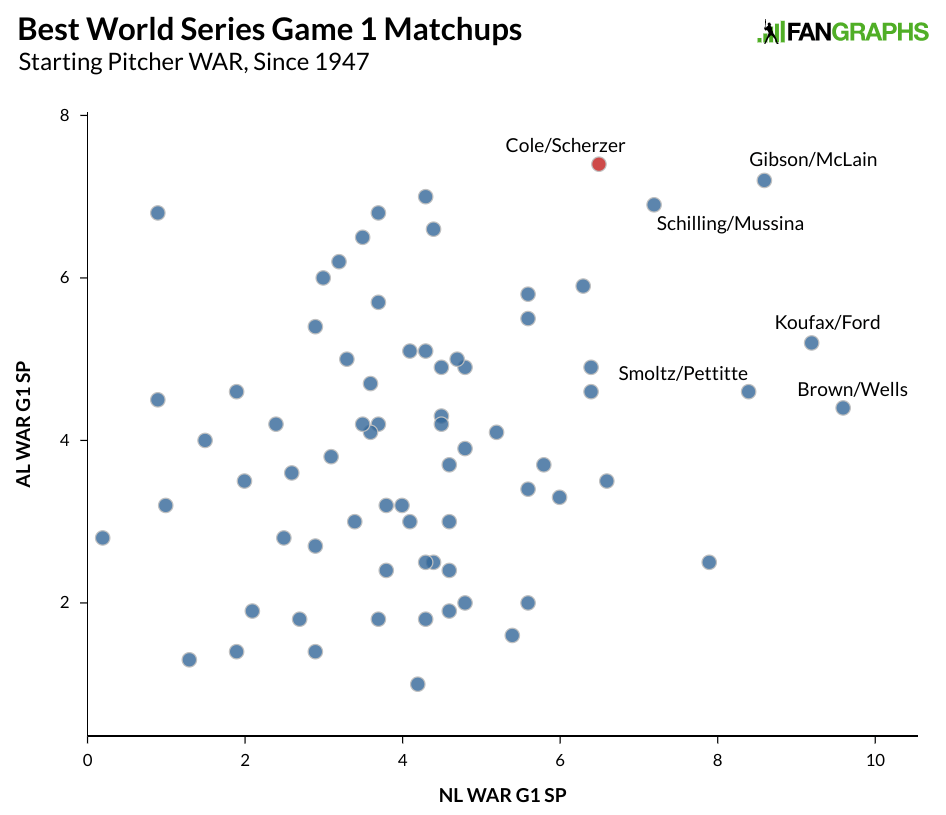

The Greatest World Series Game 1 Matchup Happens Tonight

A year ago, Chris Sale and Clayton Kershaw took the mound in the opening game of the World Series. As far as pitching matchups go, those names might have made for the greatest Game 1 of all time. Sale was coming off another great season, with a FIP and ERA both around two, having amassed roughly 14 WAR over the previous two seasons combined. Kershaw has been the most dominating pitcher of his era, winning three Cy Young Awards with another three top-three finishes plus an MVP. Of course, that version of Kershaw wasn’t pitching last season, dimming the true battle of aces wattage and putting it more in the middle tier of World Series opener pitching matchups. That’s not the case tonight, as Gerrit Cole and Max Scherzer make for what is arguably the greatest Game 1 pitching matchup in World Series history.

Max Scherzer has won two of the last three Cy Young awards and finished in second place last season. He was a favorite for the award in the first half as his 5.7 WAR essentially lapped the field, but injury trouble forced him to take some time off and he wasn’t as sharp on return. He still finished the season with a 35% strikeout rate, a 5% walk rate, a 2.92 ERA, 2.45 FIP, and 6.5 WAR, the last of which was second to only Jacob deGrom in the NL and fourth in baseball behind Gerrit Cole and Lance Lynn. Scherzer has begun to shrug off the late-season donwturn and in the last two rounds of the playoffs, he has pitched 15 innings, struck out 21, walked just five and given up just a single run. His velocity has trended up in the postseason and he’s pitching with eight days rest.

As for Gerrit Cole, he topped all pitchers with 7.4 WAR this season; since the start of 2018, only deGrom and Scherzer have more than Cole’s 13.4 WAR. He’s returned to ace status after a great 2015 season, with injuries slowing him down in 2016 and ’17. He deserves to win the Cy Young award as he heads to free agency, and he has had a brilliant postseason up to this point with 22.2 innings, 32 strikeouts, and just one run in three starts. We have arguably the best pitcher in baseball right now going up against the best pitcher in baseball over the last three (and maybe up to eight) years.

Looking only at single-season WAR, the duo is impressive for the first game of the World Series. Look at the scatter plot below, which shows all matchups for World Series openers since 1947:

Cole has the highest WAR for an American League starter in Game 1 of the World Series since at least 1947. Before that, Smoky Joe Wood put up 7.6 WAR for the Red Sox in 1912, while Lefty Grove had 8.3 WAR for the A’s in 1930, and Hal Newhouser’s 8.2 WAR paced the Tigers in 1945. Those are the only pitchers with better seasons in the American League to start Game 1 of the World Series. Scherzer’s 6.5 WAR ranks eighth among the 72 NL Game 1 starting pitchers since 1947. On average, or using geometric mean to avoid one really good starting pitcher skewing the matchup, tonight’s game is very close to the top, but not quite the best:

| Season | NL WSG1 SP | NL WAR G1 SP | AL WSG1 | AL WAR G1 SP | AVG WAR | GEO MEAN WAR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | Bob Gibson | 8.6 | Denny McLain | 7.2 | 7.9 | 7.9 | |

| 2001 | Curt Schilling | 7.2 | Mike Mussina | 6.9 | 7.1 | 7.0 | |

| 2019 | Max Scherzer | 6.5 | Gerrit Cole | 7.4 | 7.0 | 6.9 | |

| 1963 | Sandy Koufax | 9.2 | Whitey Ford | 5.2 | 7.2 | 6.9 | |

| 1998 | Kevin Brown | 9.6 | David Wells | 4.4 | 7.0 | 6.5 | |

| 1996 | John Smoltz | 8.4 | Andy Pettitte | 4.6 | 6.5 | 6.2 | |

| 2009 | Cliff Lee | 6.3 | CC Sabathia | 5.9 | 6.1 | 6.1 | |

| 1961 | Jim O’Toole | 5.6 | Whitey Ford | 5.8 | 5.7 | 5.7 | |

| 1962 | Billy O’Dell | 6.4 | Whitey Ford | 4.9 | 5.7 | 5.6 | |

| 1974 | Andy Messersmith | 5.6 | Ken Holtzman | 5.5 | 5.6 | 5.5 | |

| 2010 | Tim Lincecum | 4.3 | Cliff Lee | 7 | 5.7 | 5.5 | |

| 1985 | John Tudor | 6.4 | Danny Jackson | 4.6 | 5.5 | 5.4 | |

| 1969 | Tom Seaver | 4.4 | Mike Cuellar | 6.6 | 5.5 | 5.4 | |

| 1964 | Ray Sadecki | 3.7 | Whitey Ford | 6.8 | 5.3 | 5.0 | |

| 2011 | Chris Carpenter | 4.8 | C.J. Wilson | 4.9 | 4.9 | 4.8 | |

| 1973 | Jon Matlack | 4.7 | Ken Holtzman | 5 | 4.9 | 4.8 | |

| 2013 | Adam Wainwright | 6.6 | Jon Lester | 3.5 | 5.1 | 4.8 | |

| 2018 | Clayton Kershaw | 3.5 | Chris Sale | 6.5 | 5.0 | 4.8 | |

| 1990 | Jose Rijo | 4.5 | Dave Stewart | 4.9 | 4.7 | 4.7 | |

| 2016 | Jon Lester | 4.3 | Corey Kluber | 5.1 | 4.7 | 4.7 | |

| 1983 | John Denny | 5.8 | Scott McGregor | 3.7 | 4.8 | 4.6 | |

| 1948 | Johnny Sain | 5.2 | Bob Feller | 4.1 | 4.7 | 4.6 | |

| 2007 | Jeff Francis | 3.7 | Josh Beckett | 5.7 | 4.7 | 4.6 | |

| 1988 | Tim Belcher | 4.1 | Dave Stewart | 5.1 | 4.6 | 4.6 | |

| 1970 | Gary Nolan | 3.2 | Jim Palmer | 6.2 | 4.7 | 4.5 |

The Year of the Pitcher back in 1968 wasn’t just some clever name. It really was a year of incredible pitching. Nobody doubts Gibson’s greatness. He averaged more than 5 WAR per season before 1968 and then put up another 18.6 WAR in the two seasons following that historic 1968 campaign. Denny McLain, on the other hand, had put up a total of two wins the previous two seasons, and after a seven-win 1969 season was replacement level as a gambling suspension and arm trouble caused his lackluster rest-of-career.

As for the second-highest matchup, Schilling hadn’t been as good in his last few years with the Phillies but his time with the Diamondbacks coincided with a resurgence. Mussina’s 2001 season was the high point in a nine-year run that saw the Hall of Famer average 5.6 WAR per season. Just below Scherzer and Cole are Koufax and Ford, two Hall of Famers in the middle of their great careers. To provide some balance to the numbers above and find great seasons with some notion of staying power, I weighted the World Series season at 50% and the previous two seasons at 25% each:

| Year | NL WSG1 SP | 3-YR AVG WAR | AL WSG1 | 3-YR AVG WAR | GEO MEAN 1-YR WAR | Weighted 3-YR GEO MEAN AVG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | Max Scherzer | 6.8 | Gerrit Cole | 5.6 | 6.9 | 6.4 | |

| 1963 | Sandy Koufax | 7.1 | Whitey Ford | 5.3 | 6.9 | 6.3 | |

| 2010 | Tim Lincecum | 6.3 | Cliff Lee | 6.8 | 5.5 | 6.3 | |

| 2001 | Curt Schilling | 5 | Mike Mussina | 6.4 | 7.0 | 6.0 | |

| 1998 | Kevin Brown | 7.6 | David Wells | 4.1 | 6.5 | 5.8 | |

| 2009 | Cliff Lee | 4.4 | CC Sabathia | 6.5 | 6.1 | 5.5 | |

| 1948 | Johnny Sain | 5.1 | Bob Feller | 6.2 | 4.6 | 5.4 | |

| 1968 | Bob Gibson | 6.3 | Denny McLain | 3.1 | 7.9 | 5.3 | |

| 2018 | Clayton Kershaw | 4.6 | Chris Sale | 6.4 | 4.8 | 5.3 | |

| 2016 | Jon Lester | 4.8 | Corey Kluber | 5.9 | 4.7 | 5.2 |

Tonight’s game narrowly edges the Koufax-Ford matchup from 1963 as well as the Cliff Lee-Tim Lincecum battle, as the latter was coming off back-to-back Cy Youngs in 2008 and 2009 before a solid 2010 season. If in-season WAR is the sole determining factor in the matchup, then the Gibson-McLain battle is still number one with Schilling and Mussina in 2001 second, and tonight’s game coming in third. If you want to consider what happened in-season most, but provide a little more weight to fairly recent performances, there hasn’t been a better Game 1 matchup in at least 70 years.

Greatest World Series Rotations of All Time

Between Max Scherzer, Stephen Strasburg, and Patrick Corbin on the Nationals and Justin Verlander, Gerrit Cole, and Zack Greinke on the Astros, six of the top 13 pitchers by WAR will be starting in the first three games of the World Series.

| Name | IP | ERA | FIP | WAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gerrit Cole | 212.1 | 2.50 | 2.64 | 7.4 |

| Jacob deGrom | 204 | 2.43 | 2.67 | 7.0 |

| Lance Lynn | 208.1 | 3.67 | 3.13 | 6.8 |

| Max Scherzer | 172.1 | 2.92 | 2.45 | 6.5 |

| Justin Verlander | 223 | 2.58 | 3.27 | 6.4 |

| Charlie Morton | 194.2 | 3.05 | 2.81 | 6.1 |

| Stephen Strasburg | 209 | 3.32 | 3.25 | 5.7 |

| Shane Bieber | 214.1 | 3.28 | 3.32 | 5.6 |

| Zack Greinke | 208.2 | 2.93 | 3.22 | 5.4 |

| Lucas Giolito | 176.2 | 3.41 | 3.43 | 5.1 |

| Walker Buehler | 182.1 | 3.26 | 3.01 | 5.0 |

| Hyun-Jin Ryu | 182.2 | 2.32 | 3.10 | 4.8 |

| Patrick Corbin | 202 | 3.25 | 3.49 | 4.8 |

| Jack Flaherty | 196.1 | 2.75 | 3.46 | 4.7 |

| Zack Wheeler | 195.1 | 3.96 | 3.48 | 4.7 |

Blue = Nationals

That’s a staggering amount of good pitching packed into just one series. Even if both teams use a fourth starter, 75%-87% of all starters in the World Series will come from the list above. That has to be the best collection of present pitching talent in a World Series, right? Let’s test it out. Read the rest of this entry »