This offseason, a narrative emerged surrounding the big contract extensions we saw signed that, after a couple of slow winters, players are afraid of free agency. That narrative is not without support. First, we have the presence of all of the extensions to star-level players, which indicate that players are at least willing to forego free agency and sign long-term deals. Mike Trout, after signing his extension, told Business Insider that, “People want to stay away from free agency.” That seems like a pretty clear indicator that players have trepidations about entering the market, presumably worried that the riches once there for them are no longer available. But while I wouldn’t want to be accused of doubting Mike Trout, not all extensions are created equal, and many of the extensions we saw signed this winter were for players for whom the free agency picture was still likely rosy.

When we talk about contract extensions as an indicator of a new reluctance to participate in free agency, it’s important to distinguish between players in different phases of their careers. Deals made by players like Aaron Nola, Blake Snell, Luis Severino, Alex Bregman, or Ronald Acuna, Jr., are quite different than those for players like Trout or Chris Sale or even Nolan Arenado. Players in Acuna and Bregman’s cohort were all three or more years from free agency. If we can make assumptions about their state of mind, they seem less likely to worry about what happens when they get to free agency, though that is no doubt still a concern, and more concerned about getting there in the first place, worrying about succumbing to injury or ineffectiveness before they’re able to sign a big deal.

The chilliness of today’s market, and concerns over service time manipulation delaying free agency further, may have exacerbated those concerns, but MLB owners have been capitalizing on those fears for more than a decade. The extension that buys out arbitration and free agency years is not a new phenomena. These players present a related but importantly different case from the Trouts and Sales, who, prior to their extensions, faced free agency much sooner, while the current collective bargaining agreement is still in effect. Indeed, 10 of the big contracts agreed to this winter were for players within one or two years of free agency, making them less likely to worry about reaching free agency and more concerned about the state of the market when they get there. That is the population I’m interested in exploring today.

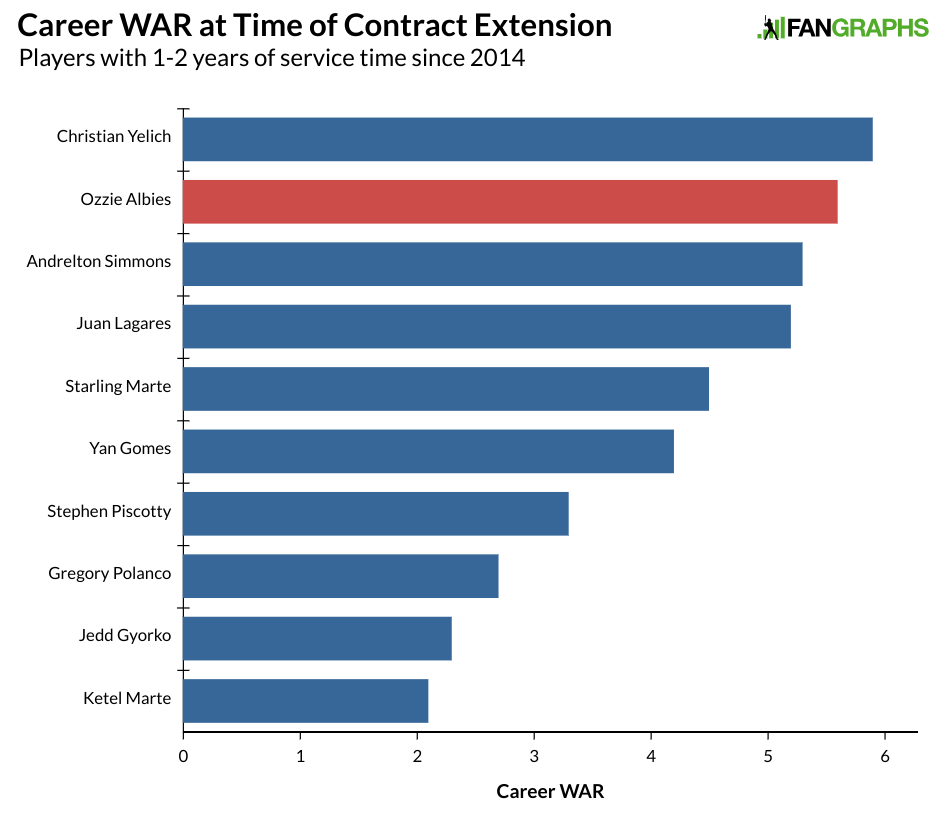

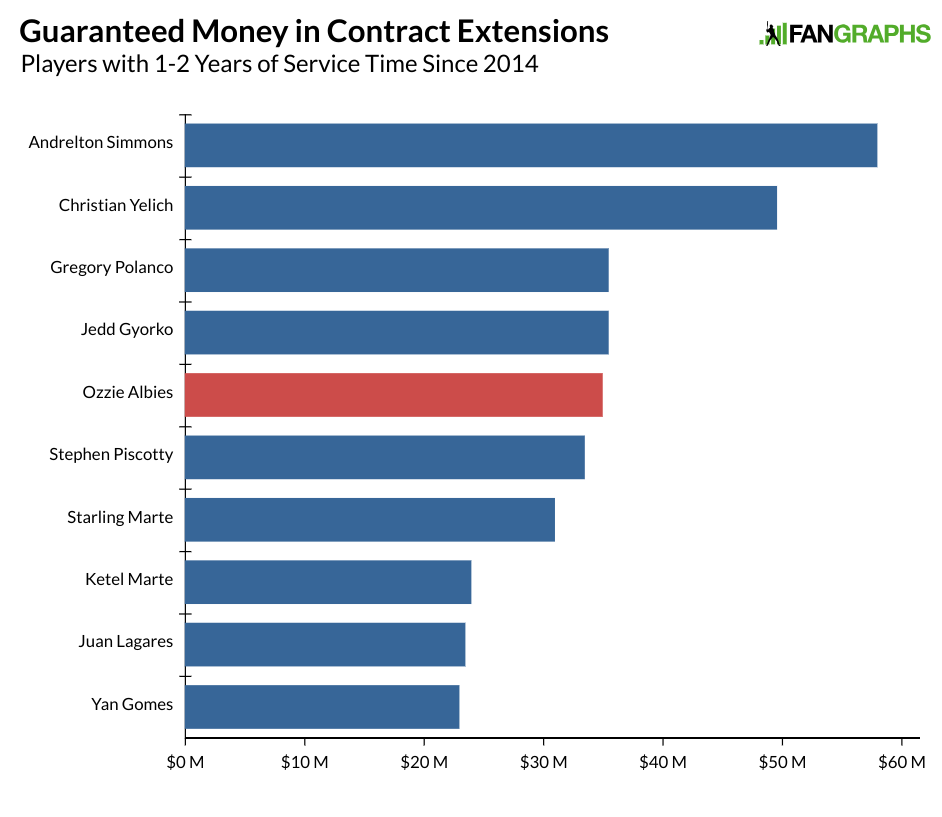

Seven recent contract extensions went to players who would have been free agents at the end of this season, with another three deals going to players who would have been free agents after the 2020 campaign. We generally see contract extensions as team-friendly deals motivated by owners wishing to provide a guarantee now in exchange for cheaper free agent years later. That reasoning is less clear when players are so close to hitting the market. If free agency was working poorly for those players who signed contract extensions one season early, then the players should be taking a discount now on what would be expected of them had they waited. To help uncover potential motivations from both the players and the owners, we need to attempt to determine the size of the discount the players took. To make such an attempt, I enlisted the readers of FanGraphs.

I asked our readers two questions. First, I asked them to gauge the contract the players would have received if they were free agents right now. Second, I asked them what those players’ expected contracts would have been had they reached free agency. There are some problems with attempting to crowdsource this way, the main one being that we already know what type of extension the players actually signed. That can have an anchoring effect. Another issue is that we know considerably less about potential market factors and player performance now compared to when free agent contracts are typically crowdsourced. Despite these issues, inviting readers, who do a pretty good job estimating contracts in the offseason, should shed some light on potential fear on the part of players.

First, here are the results of the crowd when it comes to the 10 players who signed extensions, as well as a bonus player who might.

Contract Extension Crowdsourcing Results

|

Today-Years |

Today-Total |

AAV |

After 2019/2020 Years |

After 2019/2020 Value |

AAV |

| Mike Trout |

12.8 |

$492.9 M |

$38.5 M |

11.3 |

$441.2 M |

$39.0 M |

| Nolan Arenado |

9.1 |

$276.2 M |

$30.4 M |

8.2 |

$249.6 M |

$30.4 M |

| Anthony Rendon |

7.4 |

$199.4 M |

$26.9 M |

6.7 |

$181.6 M |

$27.1 M |

| Jacob deGrom |

6.2 |

$191 M |

$30.8 M |

5.1 |

$158 M |

$31.0 M |

| Chris Sale |

6.3 |

$189.8 M |

$30.1 M |

5.3 |

$157 M |

$29.6 M |

| Xander Bogaerts |

7.5 |

$176.1 M |

$23.5 M |

7 |

$163.5 M |

$23.4 M |

| Paul Goldschmidt |

5.5 |

$148.8 M |

$27.1 M |

4.7 |

$126 M |

$26.8 M |

| Justin Verlander |

3.1 |

$89 M |

$28.7 M |

2.4 |

$68.9 M |

$28.7 M |

| Aaron Hicks |

4.9 |

$84 M |

$17.1 M |

4.4 |

$73.4 M |

$16.7 M |

| Kyle Hendricks |

4.2 |

$72.9 M |

$17.4 M |

3.5 |

$57.8 M |

$16.5 M |

| Miles Mikolas |

4 |

$69.6 M |

$17.4 M |

3.7 |

$61.9 M |

$16.7 M |

Orange=Would be Free Agent after 2020. All others after 2019.

For the most part, these figures look pretty reasonable. It’s interesting to compare similar players like Chris Sale and Jacob deGrom, as well as Kyle Hendricks and Miles Mikolas. The crowd favored Hendricks slightly at present, but when factoring in the distance from free agency, we see a slight reversal. That makes sense. We don’t see the same scenario with Sale and deGrom, and it seems possible that Sale’s early struggles might have entered into the crowd’s thinking as he saw the biggest percentage drop off of the players just one year to free agency outside of Verlander, whose proximity to retirement limits the number of years he would receive. It also seems like Anthony Rendon might be a tad underrated, or at least the crowd expects him to receive much less than Arenado, despite similar profiles.

Likely more interesting is how the players’ actual deals compared to the crowdsourced estimates. First, the players just one year from free agency.

Contract Extension Crowdsourcing Results

|

After 2019 Crowd |

Actual After 2019 Contract |

Opt-Out |

Discount |

Discount with Opt-Out |

| Nolan Arenado |

$249.6 M |

$244 M |

Yes |

2.2% |

-3.8% |

| Chris Sale |

$157 M |

$145 M |

Yes |

7.6% |

-1.9% |

| Xander Bogaerts |

$163.5 M |

$120 M |

Yes |

26.6% |

17.4% |

| Paul Goldschmidt |

$126 M |

$130 M |

No |

-3.2% |

-3.2% |

| Justin Verlander |

$68.9 M |

$66 M |

No |

4.2% |

4.2% |

| Aaron Hicks |

$73.4 M |

$70 M |

No |

4.6% |

4.6% |

| Miles Mikolas |

$61.9 M |

$68 M |

No |

-9.9% |

-9.9% |

| TOTAL |

$900.3 M |

$843 M |

|

6.4% |

1.4% |

Opt-out generically estimated at $15 M.

While anchoring to the already-known extension is certainly a factor, the seven potential free agents above basically signed for their expected free agent totals. We could argue a little about how much opt-outs are worth, but it certainly seems as though teams have received little to no discount for signing free agents. As to the crowd’s accuracy, we clearly can’t reproduce the exact same sample used in the offseason, but generally speaking, the crowd has come pretty close to forecasting the big contracts over the past five seasons, undershooting the totals by less than 10% overall.

Now, here are the three extensions signed by player who would have been eligible for free agency after the 2020 season.

Contract Extension Crowdsourcing Results

|

After 2020 Crowd |

Actual After 2020 Contract |

Opt-Out |

Discount |

Discount with Opt-Out |

| Mike Trout |

$441.2 |

$360 |

No |

18.4% |

18.4% |

| Jacob deGrom |

$158 |

$97.5 |

Yes |

38.3% |

28.8% |

| Kyle Hendricks |

$57.8 |

$43.5 |

No |

24.7% |

24.7% |

| TOTAL |

$219 |

$167 |

|

23.7% |

16.9% |

Opt-out generically estimated at $15 M.

Players two years from free agency had to take a significant discount to get their deals done. That makes sense because there is more risk for the team making the guarantee and more risk for the player to wait two years. In the case of deGrom and Hendricks, that is even more true because their 2020 contracts weren’t guaranteed as they would have been in their final year of arbitration. We see potential bargains in the last group, but the group of pending free agents above is lacking in that regard. Maybe Arenado, Sale, and Bogaerts could’ve gotten more in free agency, but all three have opt-outs that will prevent any real steals by their teams. Goldschmidt and Verlander are older, while Hicks and Mikolas don’t have long track records.

I know I’ve brought up the potential of anchoring distorting these contracts a few times, but keep in mind that the narrative that players have trepidations about free agency and are therefore taking contracts at a discount due to that fear is also prevalent. We could be seeing a general lowering of expectations for free agent contracts, but we just saw two $300 million contracts handed out plus another $140 million to Patrick Corbin. Most of the players above are closer to Machado, Harper, and Corbin compared to others who have struggled to get their desired deals.

When we see players avoiding free agency, concluding that players are afraid of the open market strikes a cord because it ties in well with recent slow free agent periods and owners generally having the upper hand over players financially. It’s not clear that these particular examples, especially the pending free agents, are a symptom of a potential larger problem. What seems to be the case is that teams have an enormous amount of money to spend and they are offering what are pretty close to free agent prices to players at the top of the market. For the players’ side, free agency is designed to get veterans large amounts of money. These contract extensions are very much a favorable outcome in service of that goal. Players get their free agent money without putting themselves at risk for another season. Could they have gotten more by hitting free agency next winter? That’s certainly possible, but the most likely scenario for most of these players is playing out the season and getting a contract very similar to the one that was already offered by their current team.

This study doesn’t address the players who have yet to see a big contract and sign away multiple free agent seasons because it takes 6-7 years just to get to free agency. It also doesn’t address the many players in the league’s middle-class who get to free agency only to fail to find desirable contracts after having their salaries capped for more than half a decade. There are certainly issues with free agency, minimum salaries, the arbitration system, the split of revenue between owners and players, and the CBA as a whole. Those concerns will no doubt drive the next CBA negotiation. But when looking at the holes in free agency, this study would seem to suggest that the big-money extensions for pending free agents is not the void you’re looking for.