Last Chance Saloon: Four Backend Starters Secure Employment

For pitchers, it’s really not optimal to show up late to spring training. Roll up to Arizona or Florida sometime in early March, and then you’re behind all your friends, still ramping up when it’s supposed to be go time. Maybe you find your form sometime in May. Maybe your season never gets off the ground. Such a fate is to be avoided, if at all possible.

And so with pitchers and catchers reporting Tuesday, Monday was, in effect, the final day to sign to ensure a regular build-up. Appropriately, there was a predictable run on the straggling starting pitchers of the free agent market. Nick Martinez went to the Rays; Erick Fedde returned to the White Sox; Chris Paddack found a life raft with the Marlins. Also, even though José Urquidy signed with the Pirates last Thursday, we’re bringing him to the party, too. Let’s talk about each of these signings in that order.

Nick Martinez Signs With Rays (One Year, $13 Million)

Martinez is the biggest name of the bunch, and he accordingly received the largest deal — $13 million for a year’s work — as reported by MLB.com’s Mark Feinsand. Of the remaining pitchers available, his 2.1 ZiPS projected WAR was third best.

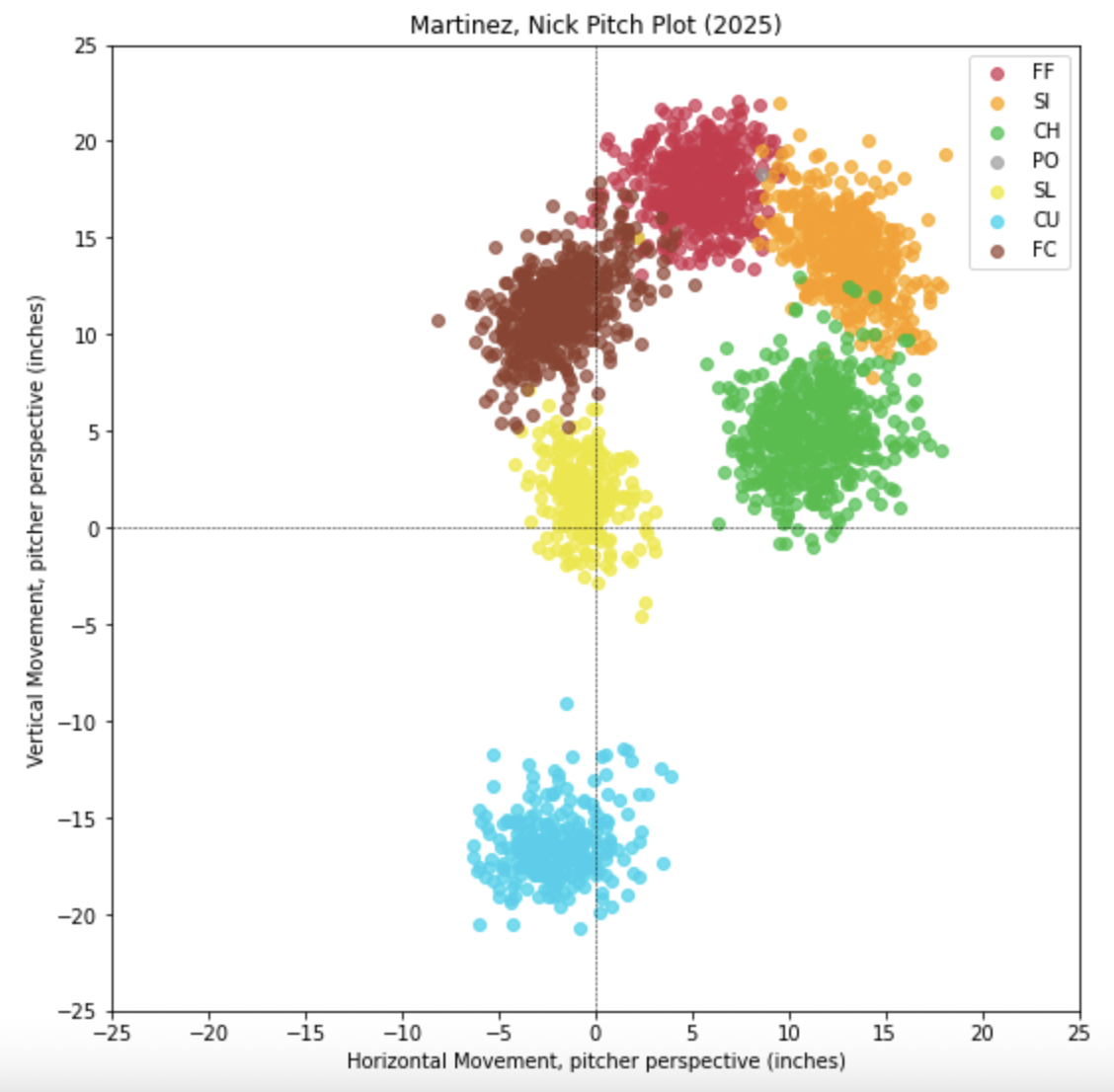

It’s unclear if he’ll assume his typical swingman role in Tampa Bay. The RosterResource crew sees him slotting into the back of the rotation, a place he thrived in the second half of 2024 with the Reds. Despite averaging just 92.6 mph on his four-seam fastball that season, Martinez leveraged a wide mix and impeccable command to deliver a 3.21 FIP over 142 1/3 innings, good for 3.4 WAR. On the strength of that campaign, he received (and accepted) the qualifying offer, bequeathing him a hefty $21.05 million for 2025.

Last offseason, I speculated that Martinez was a good candidate to repeat his surprising success due in large part to his ability to blend his pitches together. These arsenal effects, I thought, would lead to sustainable soft-contact generation, allowing for continued success in spite of a so-so strikeout rate.

In some sense, I was half-right: New arsenal metrics from Baseball Prospectus, introduced months after the publication of that article, reinforced my thesis. Martinez’s 2025 Pitch Type Probability (a measure of unpredictability) ranked in the 94th percentile among pitchers with at least 1000 pitches thrown; his Movement Spread and Velocity Spread also clocked in well above average. True to form, he limited damage on contact, holding hitters to a 34.5% hard-hit rate (90th percentile) and a .275 BABIP.

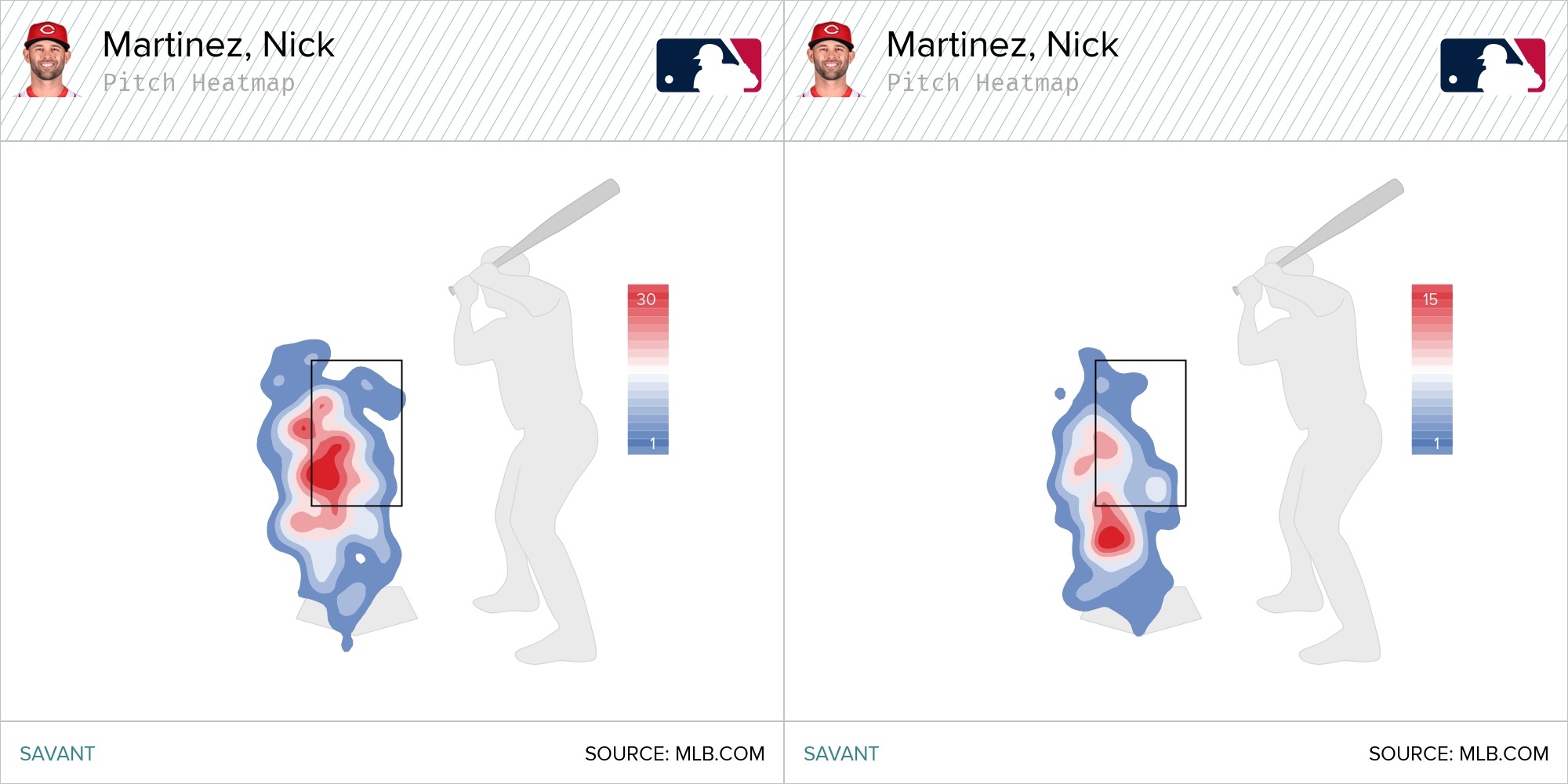

And yet Martinez’s 2025 season was a bust; his ERA jumped from 3.10 to 4.45, with the poor peripherals to back it up. After running a 3.2% walk rate in 2024, some control regression was expected. But his bat-missing went from acceptable to dire, his strikeout rate dropping nearly four percentage points. The main culprit was the changeup, which generated a huge amount of chase in 2024 and fell all the way back to Earth in 2025. The shape did not change significantly, but his command of the pitch slipped considerably. Check out how much more plate his changeup caught against left-handed hitters this season (left) versus last (right):

The changeup unlocks the entire Martinez experience, and its performance will determine whether the Rays will be getting a durable but unexciting innings-eater or a guy you might trust to start Game 3 of a Divisional Series. Either way, he improves the Tampa Bay staff for 2026, giving the team insurance against the wild whims of Joe Boyle. And in the case of a Boyle breakout, Martinez can easily shift back into his familiar swingman role.

Erick Fedde Signs With White Sox (Contract TBA)

It was mad ugly for Fedde in 2025. He started the year in St. Louis, pitching a little over 100 innings of exactly replacement-level ball; at the trade deadline, the Braves picked him up for a handful of gumballs, hoping he’d hoover up some innings in a lost season. Three weeks later, they straight up released him; the Brewers brought him in for a few mopup opportunities before hitting him with a DFA on the final day of the regular season.

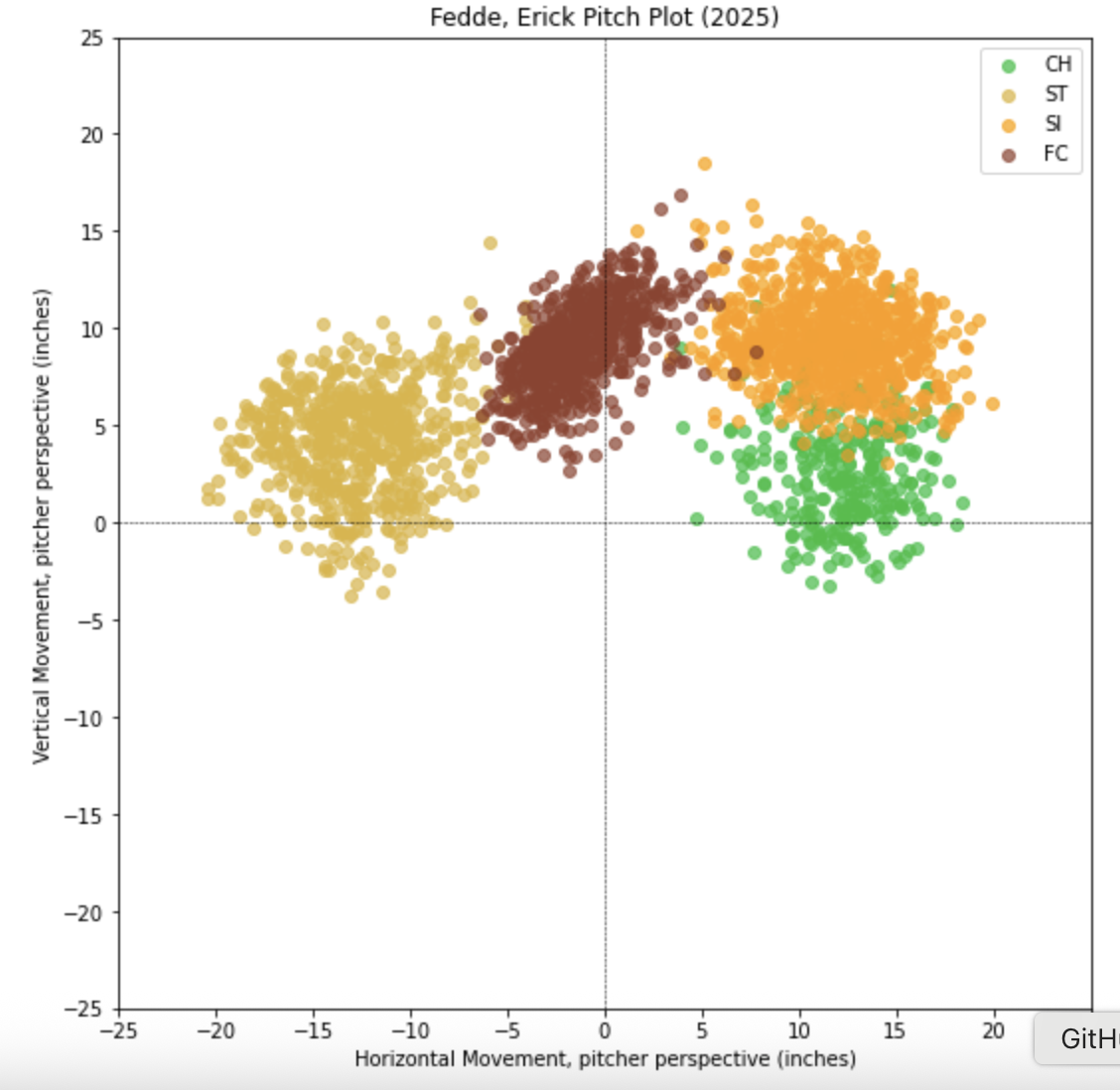

That’s not what you want. Fedde’s east-west attack fell apart in 2025; excluding Rockies hurlers, his 13.3% strikeout rate was worst in baseball (minimum 100 innings pitched.) Perhaps fatally, his walk rate ballooned as he opted to pitch around hitters instead of challenging them in the zone.

But what better place to resurrect his career? Those handful of months on the South Side in 2024 were the best he’s pitched since his triumphant return from the KBO. In 21 pre-trade deadline starts that year, Fedde bullied righties with his sinker-sweeper combo, and jammed enough lefties with his cutter to viably work his way through lineups. A 3.11 ERA earned him a deadline promotion to a contender, and he proceeded to pitch roughly as well as a Cardinal, though the team ultimately missed the playoffs.

Fedde was still pretty good against righties in 2025, but lefties smoked him to the tune of a .389 wOBA. His cutter lost a crucial couple inches of glove-side bite, and so the pitch tended to finish middle-up instead of on the inner edge. A perfectly straight 90-mph cutter is fodder for tanks; with no four-seam option on the table, Fedde was faced with the difficult choice of getting aggressive with subpar stuff or aiming at too-fine targets.

If getting back with pitching coach Brian Bannister can help Fedde gain back those two inches of break on the cutter, the White Sox can expect him to deliver on his presumably modest deal.

Chris Paddack Signs With Marlins (One year, $4 million)

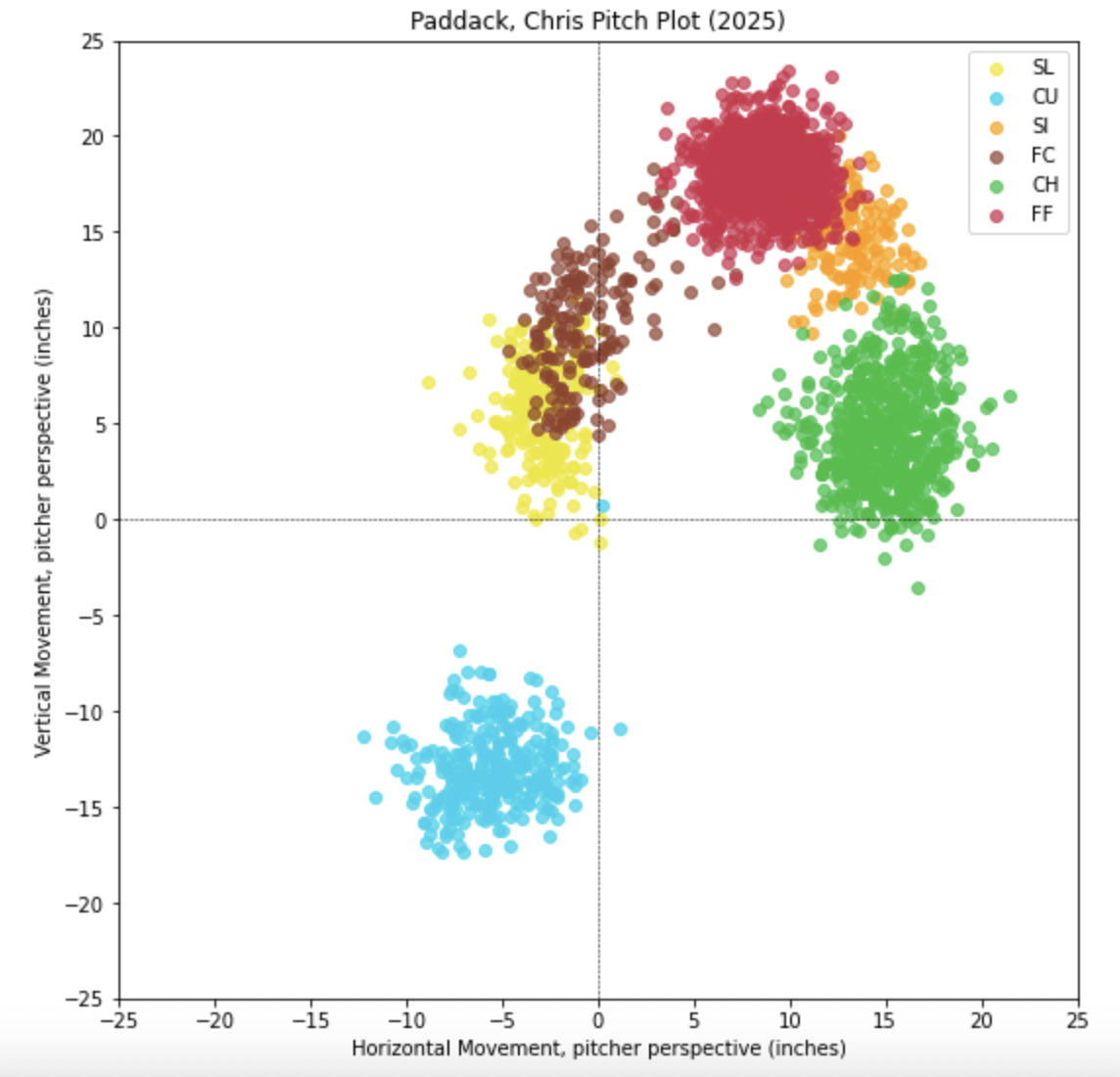

Paddack’s plan of attack is pretty straightforward, venturing not much further than a carry fastball and a butterfly changeup. When you throw a carry fastball nearly half the time at mediocre velocity, you’re going to give up a lot of home runs. So it’s been for Paddack his entire career, and never more so than in 2025, when he gave up a career-high 31 chucks across his 158 2/3 innings of work.

With Martinez and Fedde at least, you can squint at them and see an unlikely path to a 3-WAR season. Paddack, however, presents no such upside. He is what he is: a guy with reliably excellent command and not enough stuff to miss bats or stay off barrels. This blurb is already pretty negative, but still, I must admit that I am surprised that he received a guaranteed big league deal. (And for $4 million, no less.)

I’m not even really sure I understand this signing for the Marlins. RosterResource projects this signing to kick Janson Junk into a long relief role. Junk is, to my eye, a better version of Paddack, featuring similarly excellent command and a carry fastball from a high arm angle. But Junk can throw a pretty good breaking ball; Paddack’s extreme pronation bias prevents him from spinning the ball with any effectiveness. Unless the Marlins are planning to imminently ship out Sandy Alcantara, I don’t see what Paddack brings to their club at present. Perhaps he could work as an unconventional relief arm, throwing only fastballs and changeups.

José Urquidy Signs With Pirates (One Year, $1.5 million)

Remember him? Urquidy’s last full season of work was all the way back in 2022, when he racked up 164 1/3 innings for a World Series-winning Astros club. In the three years hence, he’s battled shoulder problems and then, finally, a torn elbow ligament, causing him to miss the entire 2024 season and nearly all of 2025.

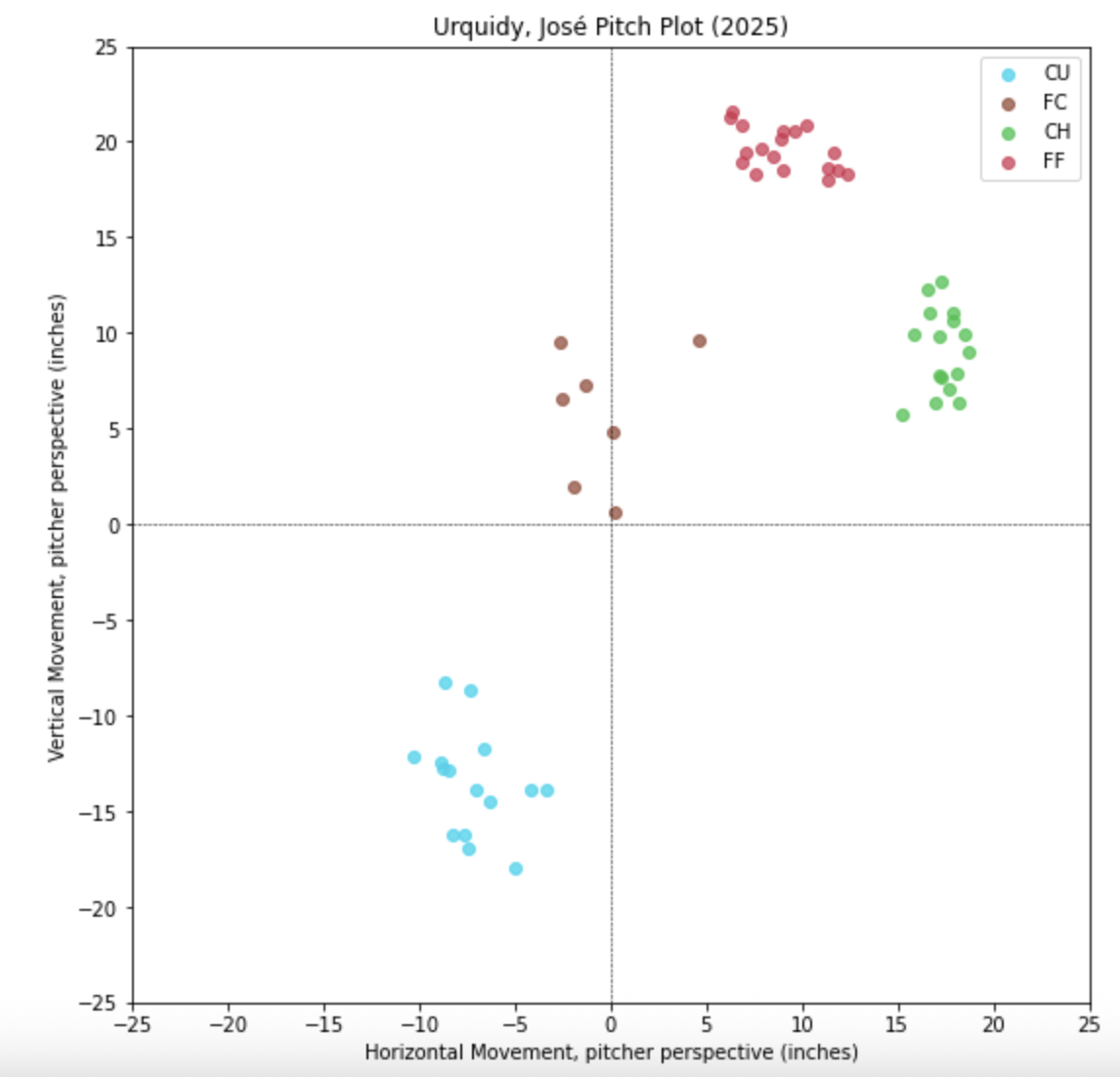

Crucially for the purposes of providing analysis in this blurb, Urquidy did briefly resurface in Detroit for 2 1/3 innings of work in September, allowing us to compare his stuff to where it was before the injury. Surprisingly, it was mostly the same. Both before and after, Urquidy possessed a four-seam fastball with crazy carry (nearly 20 inches of induced vertical break), a changeup with respectable vertical separation, and a slow two-plane curveball, and his fastball velocity was nearly identical, 93.1 mph in 2023 and 93.0 mph in 2025. But there was one pivotal difference: Urquidy’s sweeper, which was completely incongruous with the rest of his arsenal and racked up a bunch of whiffs in 2023, did not resurface in his brief big league stint last year.

Like Paddack, the arsenal characteristics (93-mph carry fastball) will ensure a bushel of tanks. Can Urquidy limit damage around the homers enough to hold the fort down until the return of Jared Jones? I think it might come down to the state of that sweeper. Otherwise, I’m not sure he has an out pitch against same-handed hitters. As far as backend bets go, there are worse ideas than giving $1.5 million to a guy who reliably beat his FIP for years prior to the injury. The Pirates aren’t asking for much, and Urquidy seems reasonably likely to meet those low expectations.