Checking in on Justus Sheffield

On the surface, Justus Sheffield’s developmental journey looks pretty smooth. He was a first-round pick back in 2014. He’s been a consensus top 50 or so prospect since the Obama administration — never much higher than that, but only rarely lower (Eric and Kiley had him ranked 60th overall and first in the Mariners system preseason; he’s since dropped to 109th and seventh respectively). His velocity has not materially changed. He’s suffered a few bumps and bruises, but nothing ever sidelined him long. Twenty-three years old now, he’s cracked a big league rotation right on schedule for a high school draftee of his caliber.

Statistically, he’s been consistent as well. With the exception of a very poor early season spell this year, he’s maintained an ERA under 3.40 at every minor league stop. His strikeout numbers have almost always hovered just above a batter per inning, his walk totals around 3.5/9. He typically generates more grounders than flies. Every year, a new level; every year, the same successes.

Yet Sheffield’s path has actually meandered a bit. As a high schooler, the lefty was seen as an athlete who would have no trouble throwing strikes and a guy who could develop three plus pitches. Two years into his career, he effectively pocketed one of them, shelving his curve in favor of a hard slider. He also grew quite a bit soon after the draft. Between the added weight, a new pitch mix, and a difficult delivery to repeat, his control suffered and whispers about a bullpen role grew louder even as he continued missing bats. His velocity, while stable in the aggregate, has periodically fluctuated on either side of the low-90s. We’ve learned that Sheffield’s fastball has a very low spin rate (more on that later).

He also got traded twice. On the one hand, Sheffield has had the opportunity to hone his craft under the tutelage of two of the sport’s finest pitching development staffs. On the other, those same clubs ultimately decided to work with different pitchers. As he’s matured, and as his fastball looks less like a bat-misser and his changeup remains a work in progress, he’s increasingly relied on his slider. The soothing consistency in his production belies a conflict between the quality of that slider and the reality that he must throw something else eventually. How that conflict resolves itself will shape his ultimate role.

The bullpen has long been the logical end point here. As a starter, Sheffield sits in the low-90s, touching 95 or a tick better at his strongest. In relief, he’d throw even harder. Pair increased velocity with a slider that earns a whiff nearly a quarter of the time he throws it, and you’ve got a late-inning reliever. Lefties, even ones with serviceable changeups, usually peak as eight-inning guys out of the pen. But on paper, Sheffield’s cocktail is good enough to close.

And yet, Sheffield keeps having just enough success in the rotation to make you think it’s possible he’ll turn the trick in the big leagues too. For everything that makes evaluators question his ability to start — the deep counts, the inability to miss bats with his fastball, a cambio that he doesn’t seem to completely trust yet — there are still reasons to believe he’s a budding mid-rotation arm.

That all starts with the slider. With mid-80s velocity and tight, very late downward action, it’s comfortably a plus pitch and it may be better than that when all is said and done. Lefties haven’t and won’t do much with it; with Sheffield’s relatively low slot, it’s a nightmare to pick up. But throughout his short big league career, righties have actually had much more trouble putting the bat on the ball against it than lefties have. Critically, it’s a pitch that he can use in several different ways. He’s adept at starting the pitch out in the middle of the plate and letting it run down and in toward a righty’s back foot.

He can also tighten the ball up a little bit and coax a whiff on sliders on the outer edge of the plate too.

Sheffield needs to be careful with that: he doesn’t have pinpoint control, and when his slider has flattened out, he’s been punished. Adam Engel, of all people, drove a hanging slider into the upper tank in his last start. Earlier in the year, Gary Sánchez nearly hit one out of T-Mobile Park on the same kind of mistake. Sliders have a heavy platoon split for a reason, and to survive as a starter, Sheffield’ll either need to command his slider better or find an additional weapon for righties. The change could fill that role: at its best, it’s at least average, and he’s missed a few bats with it thus far. Too often though, it flattens out.

The second point in his favor is one that may look like a weakness at first glance: his fastball. Sheffield’s heater has pretty good velocity — on the 20-80, it’s above average — but it has one of the very lowest spin rates in baseball. That may not do it justice: Per Statcast, at just 1852 RPM’s, his fastball’s spin rate is in the league’s first percentile. That extremely low spin rate means that it drops much more than your average fastball on its way to the plate, and consequently it’s not a pitch he’s all that likely to miss bats with. And indeed he has not: major league hitters have swung and missed at fewer than 5% of his fastballs.

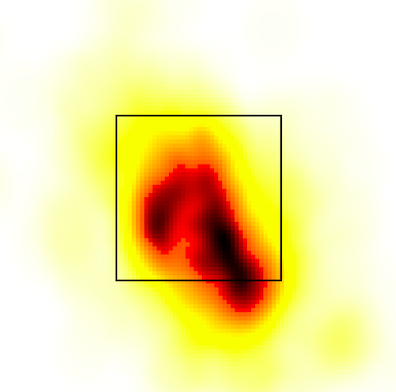

Sheffield doesn’t lean on the No. 1 as so many pitchers from previous generations did, though. He’s thrown it less than 50% of the time as a big leaguer, with a lower rate as a starter in 2019 than in his bullpen cameo in New York late last summer. While not an unusually low usage rate in today’s game, it does seem that he’s aware his bread and butter for a whiff is the slider. Instead, he uses the fastball to try to get grounders, and he’s been pretty successful at that. He’s consistently generated more grounders than flies as a minor leaguer, and more than half of the contact he’s allowed in the majors thus far has come on the ground. As you’d imagine, he generally keeps the pitch down:

In a nutshell, that’s the formula: Generate grounders with the fastball, use the slider to get whiffs. Mix in a change every so often, and you have a pitcher racking up plenty of each of the three true outcomes. Will it be enough to hold in the rotation over the long haul?

Even at this relatively late stage of Sheffield’s development, his career implies that any rigid analysis of his future prospects would be a guessing game. We’ve seen him drop one of his best weapons, learn a new favorite pitch, discover just how little spin he gets on his heater, and periodically lose and regain his arm strength. Just in 2019, we watched as Triple-A hitters torched him for nearly 2 HR/9 and saw the same guy fan more than a batter per inning in the big leagues a few months later. We haven’t always known how Sheffield would look in two days, much less two years.

Still, the safe thing to say is the familiar one. Sheffield doesn’t have ace upside, but he could be a mid-rotation arm so long as he keeps his slider out of the middle of the plate. His reliance on the breaking ball and spotty command suggests that he won’t be efficient, but there’s a chance he can grunt out five or six clean innings often enough to stick as a solid No. 3. If the meatball remains a problem, a bright future in the bullpen awaits.

As Sheffield has made himself into a very different pitcher than he once was, the “if/then” analysis that caps any report on his progress has barely budged. It’s funny how that can happen to certain guys. Five years into his career, the consensus is still as certain as ever that he’s one of two things, but we’re not a whole lot closer to determining which one.

With a spin rate that low does he throw a sinker?

He grips it like a four-seamer but it has sinking action.

This raises a question I’ve wondered sometimes about guys with this kind of low spin/low rise 4-seamer: wouldn’t they be better off just dropping the 4-seamer and developing a sinker instead? I know sinkers are on life support in terms of being an effective pitch, but on the other hand, 4-seamers like Sheffield’s are almost universally awful. Right now he’s basically just throwing a flat, straight sinker, wouldn’t he be better off altering the grip and trying to get more sink and some run on it? Obviously it’s not that easy to just pick up a new pitch, but it seems like something that should’ve been explored at some point for guys like him.

Maybe he’ll make it work by McCullersing and using the 4-seamer as his secondary pitch behind the breaking balls, but it still seems like any sort of sinker (even with the pitch falling on tough times league wide) would be a preferable fastball to a definitely poor 4-seamer.

Telling a guy with command issues that he should change his grip to something he’s never thrown for better hypothetical movement (from his arm angle I don’t think a 2 seam grip would actually get much arm side run)

Manaea is basically the same exact pitcher and he throws a 4seam, and from that arm angle, you probably get more movement on a 4 seam grip than a 2 seam