Cooperstown Notebook: Born in the Fifties

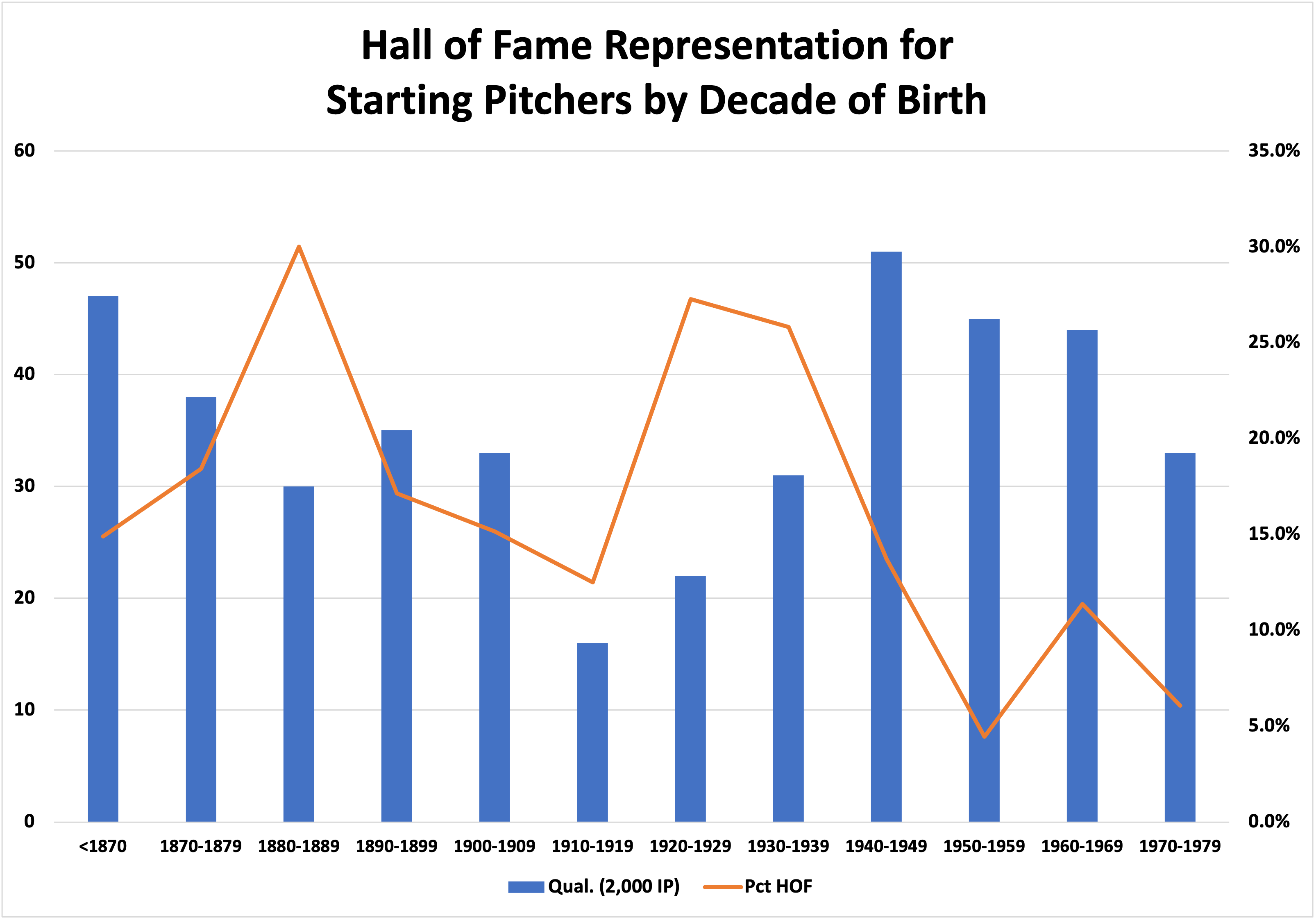

It’s small potatoes in the context of what’s going on (or not) in the baseball industry and the rest of the world, but so far as the Hall of Fame goes, the problem in a nutshell is this: Half of the starting pitchers who are in the Hall and were born in the 1950s are named Jack Morris. While there’s no need to relitigate the polarizing battle that forestalled his eventual election — been there, done that — the real issue, to these eyes, is that the gruff ex-Tigers workhorse is the only starter in the Hall born after 1951 and before ’63. When stacked up against other enshrined starters, his credentials are modest at best, and so his presence in the plaque room feels like an indictment of the quality of his peers.

The reality is that Morris won battles of attrition, first against the forces that reshaped the role of the starting pitcher following the introduction of the designated hitter in 1973, and then against the voting bodies that were slow to recognize the strength of those forces. He was a throwback, and in the arguments over his merits he became a symbol for a bygone era. Backed by strong offenses, he piled up innings while having less success preventing runs than his the best of his peers, but more success avoiding injuries or replacement by pinch-hitters and relievers. Plus, he won a few big games in October.

For all of that, I did not have Morris or any specific pitcher in mind when I began exploring ways to modernize JAWS to better account for the changes in starting pitcher workloads that have occurred over the past century and a half. After nearly two decades of using my Hall of Fame fitness metric, I know the contours of the position-by-position rankings reasonably well, and so I had a pretty good idea in advance which ones would be helped by whatever adjustments I settled on — that while knowing that those changes wouldn’t be so radical as to upset the entire system. That said, I suspected that shining a brighter light on some of those players would particularly resonate with fans of a certain age, particularly as I worked my way through history and reached the frame of reference of players I’m old enough to have watched. I don’t cross paths with a lot of fans of Jim McCormick or Wes Ferrell these days, but Luis Tiant is another matter.

My examination of that group — including Tiant, who was born in 1940 — was just a prelude to the next sets of pitchers, who as a group are drastically underrepresented in Cooperstown and who most need their careers viewed with a fresh perspective if we’re to change that. I’m not talking about opening the floodgates or summoning the ghosts of Frankie Frisch and Bill Terry, but when Morris and Bert Blyleven (b. 1951) are the only pitchers born in the 1950s who are enshrined, it seems worthwhile to iron out some inequities.

Hence S-JAWS, the experimental version of my metric and an attempt to reduce the skewing caused by the impact of 19th-century and dead-ball era pitchers who piled up totals in excess of 400, 500, or 600 innings at their peaks. S-JAWS prorates peak WAR credit for any heavy-workload season to a maximum of 250 innings, and it’s now the default at the starters’ Baseball Reference page, though the original recipe version is still there.

Where I raced through nearly a century’s worth of pitchers in my previous installment — McCormick was born in 1856, Rick Reuschel in 1949 — here I’m going to focus on just this 10-year period in question. And where my previous tables only presented the top-ranked outsiders for the various periods under discussion, this list is bookended by the aforementioned odd couple:

| Name | Born | WAR | WAR7 | WAR7Adj | JAWS | S-JAWS | Yrs | W-L | ERA | ERA+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bert Blyleven+ | 1951 | 94.5 | 50.3 | 44.8 | 72.4 | 69.6 | 1970-1992 | 287-250 | 3.31 | 118 |

| Dave Stieb | 1957 | 56.4 | 44.5 | 41.9 | 50.4 | 49.1 | 1979-1998 | 176-137 | 3.44 | 122 |

| Orel Hershiser | 1958 | 56.0 | 40.1 | 39.0 | 48.1 | 47.5 | 1983-2000 | 204-150 | 3.48 | 112 |

| Frank Tanana | 1953 | 57.1 | 38.1 | 36.6 | 47.6 | 46.9 | 1973-1993 | 240-236 | 3.66 | 106 |

| Ron Guidry | 1950 | 47.8 | 38.0 | 37.0 | 42.9 | 42.4 | 1975-1988 | 170-91 | 3.29 | 119 |

| Dennis Martinez | 1954 | 48.7 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 41.0 | 41.0 | 1976-1998 | 245-193 | 3.70 | 106 |

| Jack Morris+ | 1955 | 43.5 | 32.5 | 31.2 | 38.0 | 37.4 | 1977-1994 | 254-186 | 3.90 | 105 |

As noted previously, one aspect of this historical anomaly is that four of the Hall’s eight enshrined relievers (Dennis Eckersley, Rich Gossage, Lee Smith, and Bruce Sutter) were born in the 1950s as well, which may have peeled away a bit of the talent, though from that group only Eckersley had any sustained major league success as a starter. Setting that aside, the five pitchers between Blyleven and Morris in the table above all had substantial careers, spending at least parts of 14 seasons in the majors and throwing over 2,300 innings. It would be inaccurate to say that all of them were on potential Hall of Fame path but were waylaid. Martinez was the Bartolo Colon of his day, a pitcher who found his way out of a detour (in his case, alcoholism), improved with age, and became beloved in the process, but even with an exceptionally productive run from ages 33 to 42 (129 wins, 128 ERA+, 41.2 WAR), the first half of his career didn’t position him for a run at a bronze plaque. As for the other four, their fates weren’t as absurd as those of the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant Softball Team ringers, but each had to surmount injuries and other obstacles, and some were more successful than others. Their Hall of Fame chances, however, vanished into the Springfield Mystery Spot.

In another break from the previous installment, I’m going to work from the bottom of this list to the top, which isn’t to say that I’m arguing on behalf of all of these pitchers.

Ron Guidry

Guidry was mismanaged early in his career. He battled control problems in the minors and spent 1974–76 (his ages 23–25 seasons) working as a reliever in the upper minors. For some reason, manager Billy Martin, who took over in late 1975, didn’t take to him, and neither did owner George Steinbrenner. At one point during the 1976 season, Guidry languished in the bullpen for 47 days without getting called upon, and he didn’t get a real shot at a rotation spot until late April of the following year. Once he did, he quickly broke out and helped the Yankees to back-to-back World Series wins in that year and the next, turning in an incredible Cy Young-winning season in 1978 (25–3, 1.74 ERA, and I don’t even have to look those numbers up).

Guidry helped the Yankees to another pennant in 1981, made a total of four All-Star teams, had additional second-, third-, and fifth-place finishes in the Cy Young voting, took home four Gold Gloves, and topped 20 wins two more times. Alas, bone spurs in his elbow and a tear in his rotator cuff limited him to fewer than 200 innings after age 35, and the Yankees’ dysfunction didn’t help. He retired after spending part of 1989 at Triple-A Columbus, finishing with just 2,332 innings, too few to build up counting stats that would catch the eyes of many Hall of Fame voters. As summarized by his 107 score on the Hall of Fame Monitor, he had enough impressive accomplishments to persist on BBWAA ballots for nine years despite maxing out at just 8.8%.

I don’t see Guidry as a viable candidate in light of S-JAWS, but I’ll point out that at the 110th spot of the rankings, he’s well ahead of Morris (163rd) and 10 other non-Negro Leagues Hall of Famers, most of whom had short careers as well.

Frank Tanana

Once upon a time, Tanana appeared to be on a fast track to Cooperstown. Chosen 13th in the 1971 draft out of a Detroit high school, he debuted with the Angels just two months after his 20th birthday in September 1973 as a southpaw who could pump his fastball into triple digits to pair with righty teammate Nolan Ryan, albeit with much better control. Through 1978, his age-24 season, Tanana made three All-Star appearances, won strikeout and ERA titles (1975, with 269, and ’77, with 2.54, respectively), had two top-four Cy Young finishes, and notched 84 wins. Among post-integration pitchers, only cautionary tale Dwight Gooden (100), Blyleven (95), and two-time Cy Young winner Denny McLain (90) had more wins, and only Blyleven (37.2) surpassed Tanana’s 31.2 WAR by that age.

Alas, Tanana was used heavily during that stretch, averaging 259 innings and 16 complete games over the 1974–78 span. He had six starts of 10 innings or more in that span, five with double-digit strikeout totals, a 17-strikeout, nine-hit complete game, and a 15-strikeout, eight-hit complete game; just thinking of what those pitch counts might have been makes my stomach hurt. He’s second in complete games (83) and third in innings (1,321) among those 24-and-under hurlers, behind Blyeleven in both stats, plus Larry Dierker (1,409.1) in the latter. By that point — still a primitive time for sports medicine — he had already battled elbow inflammation and started losing velocity. Forced to reinvent himself as a junkballer, Tanana developed an outstanding slow curve but missed two months with a rotator cuff injury in 1979. Nonetheless, he managed to stick around the majors until 1993, spending time with the Red Sox, Tigers (an eight-year stretch that included their 1987 AL East winners), Mets, and Yankees. His 2,773 strikeouts ranked 14th at the time he retired; it’s still a respectable 25th overall and fifth among lefties, 103 ahead of Clayton Kershaw.

Tanana’s run prevention wasn’t good enough to build up a store of accolades that would make him a viable Hall candidate. He never made an All-Star team after 1978, let alone merited a Cy Young vote, but at 82nd on the S-JAWS list, he’s ahead of 17 enshrined starters, including ones as diverse as Sandy Koufax, Whitey Ford, and the recently-elected Jim Kaat as well as the sub-Morris guys.

Orel Hershiser

I covered his candidacy at greater length for the 2019 Today’s Game ballot, where he landed in the “fewer than five votes” camp while Smith and Harold Baines were elected. As I noted at the time, Hershiser’s career was more than just one big year, but what a year 1988 was. He won 23 games, completed 15, and tossed eight shutouts — numbers that led the NL, the last of those capped by his setting a still-standing record with 59 consecutive scoreless innings, surpassing that of Don Drysdale. His heroics in the postseason helped him capture the 1988 NLCS and World Series MVP awards as his banged-up Dodgers squad upset the heavily favored Mets and A’s. Not only was he the unanimous winner of the NL Cy Young Award, but he also netted Sports Illustrated’s Sportsman of the Year and the Associated Press’ Male Athlete of the Year awards as well.

“The Bulldog” — so nicknamed by Tommy Lasorda as a rookie to inspire him to pitch more aggressively — never equaled those heights again, but he showed incredible tenacity in an 18-year major-league career bifurcated by a 1990 shoulder injury. He ranked as the NL’s most valuable pitcher for a six-year stretch (’84–89) before his injury, including a second-place finish in ’87 (6.4 WAR) and back-to-back firsts in ’88 (7.2) and ’89 (7.0). The latter season was obscured by dreadful offensive support, as he dropped to 15–15 despite a 2.31 ERA; his 149 ERA+ was identical to the previous year and led the NL as well.

After leading the NL in innings for three straight seasons — his 788.1 were more than anybody besides Roger Clemens (799) and Dave Stewart (794.2) — Hershiser was diagnosed with damage to both his rotator cuff and labrum in April 1990. He underwent a groundbreaking surgery by Dr. Frank Jobe, best known for his innovation in saving Tommy John’s career. Jobe reconstructed Hershiser’s anterior capsule and tightened the ligaments in his right shoulder. It took 13 months for Hershiser to return to the majors and two years for the scar tissue to harden. Though he was never again as dominant, he spent the remainder of his career demonstrating his (bull)doggedness, serving as an above-average starter for Cleveland as it won two AL pennants and providing some postseason heroics along the way. For his career, he went 8–3 with a 2.59 ERA in 132 postseason innings.

Hershiser is 76th in S-JAWS, six spots ahead of Tanana, with John, current BBWAA candidates Mark Buehrle and Andy Pettitte, Hall of Famer Joe McGinnity, and 19th-century hurler Tommy Bond separating the two. More on that ranking below.

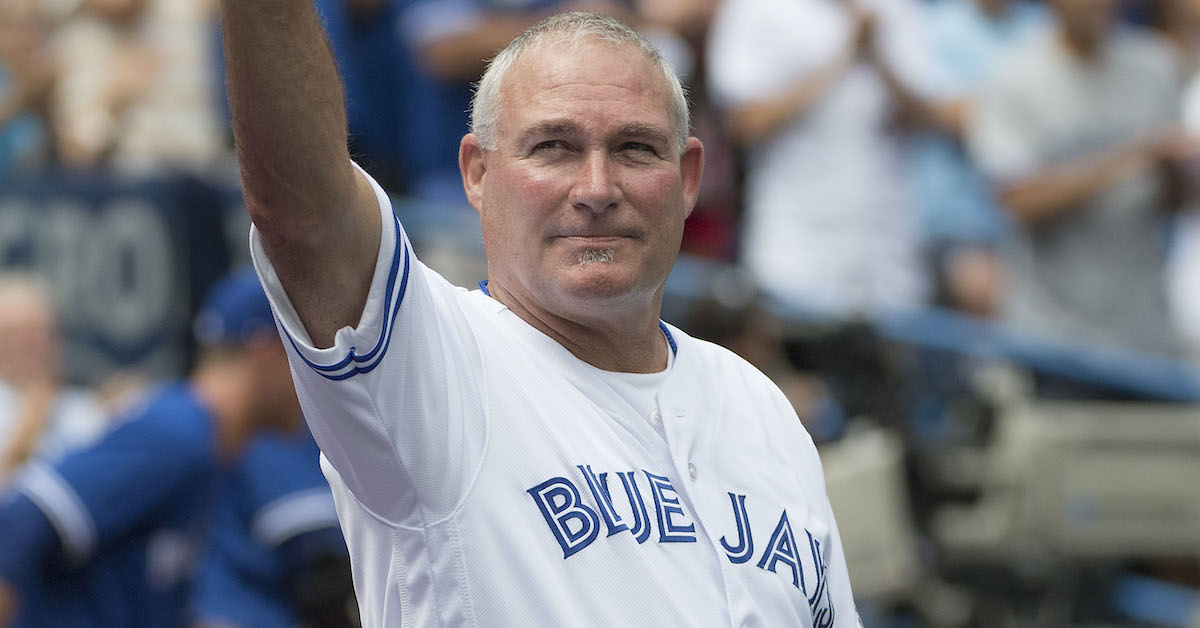

Dave Stieb

Improbably enough, I have never written more than a couple paragraphs at a time about Stieb, whose lone year on the BBWAA ballot was 2004, the year I introduced the system that became JAWS. Back then I only had the space to quickly dispatch the 10 candidates — including Blyleven, Morris, John, Martinez, and childhood favorite Fernando Valenzuela — in one sitting, so even then I wrote short on Stieb. This seems like the right venue to tell his story with a bit more length than I’ve permitted myself for the others within this series.

One of the big selling points for the candidacy of Morris was that his 162 wins and 2,443.2 innings led all starting pitchers during the 1980s. The most valuable pitcher for that stretch, in retrospect, was Stieb. Some of that has to do with the years used as cutoffs, as a few mid-decade arrivals were better on a prorated basis, but head-to-head with Morris, the comparison isn’t even close:

| Rk | Player | Yrs | Age | To | IP | W-L | ERA | ERA+ | WAR | WAR/250 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dave Stieb | 1980-89 | 22-31 | 1989 | 2328.2 | 140-109 | 3.32 | 126 | 48.1 | 5.2 |

| 2 | Bert Blyleven+ | 1980-89 | 29-38 | 1989 | 2078.1 | 123-103 | 3.64 | 113 | 38.1 | 4.6 |

| 3 | Roger Clemens | 1984-89 | 21-26 | 1989 | 1284.2 | 95-45 | 3.06 | 139 | 35.5 | 6.9 |

| 4 | Bob Welch | 1980-89 | 23-32 | 1989 | 2082.1 | 137-93 | 3.21 | 113 | 35.2 | 4.2 |

| 5 | Fernando Valenzuela | 1980-89 | 19-28 | 1989 | 2144.2 | 128-103 | 3.19 | 111 | 33.1 | 3.9 |

| 6 | Orel Hershiser | 1983-89 | 24-30 | 1989 | 1457.0 | 98-64 | 2.69 | 132 | 32.9 | 5.6 |

| 7 | Bret Saberhagen | 1984-89 | 20-25 | 1989 | 1329.0 | 92-61 | 3.23 | 128 | 32.0 | 6.0 |

| 8 | John Tudor | 1980-89 | 26-35 | 1989 | 1622.2 | 104-66 | 3.13 | 124 | 31.1 | 4.8 |

| 9 | Dwight Gooden | 1984-89 | 19-24 | 1989 | 1291.0 | 100-39 | 2.64 | 132 | 30.6 | 5.9 |

| 10 | Nolan Ryan | 1980-89 | 33-42 | 1989 | 2094.0 | 122-104 | 3.14 | 111 | 30.4 | 3.6 |

| 11T | Jack Morris+ | 1980-89 | 25-34 | 1989 | 2443.2 | 162-119 | 3.66 | 109 | 30.3 | 3.1 |

| Charlie Hough | 1980-89 | 32-41 | 1989 | 2121.2 | 128-114 | 3.67 | 112 | 30.3 | 3.6 |

The barest outline of his origin story is interesting enough. Stieb was a fifth-round draft pick in 1978 out of Southern Illinois University who reached the majors just over a year later, that despite having spent the bulk of his first professional season as an outfielder. The details really bring it to life. He earned Sporting News All-American honors as an outfielder during his junior season (1978) at SIU, hitting .394 with 12 home runs and 48 RBIs. Though he had never pitched competitively before, he doubled as an emergency reliever, pitching a total of 17 innings.

As fate would have it, legendary Blue Jays director of player development Bobby Mattick lucked into seeing one of Stieb’s rare pitching appearances while scouting him. As told by Sports Illustrated’s Ron Fimrite in 1983:

They had come to the Eastern Illinois University campus specifically to scout this Southern Illinois outfielder. And they’d been disappointed. Another Toronto scout, Don Welke, had said the boy could run, throw and hit with some power. But Mattick and [scout Al] LaMacchia had their doubts. “I didn’t like his swing,” says Mattick. They were prepared to write the prospect off when—what’s going on here?—he came in to pitch.

It wasn’t the first time Dave Stieb had taken the mound for the Salukis. He’d been pressed into duty earlier in the college season as an emergency pitcher by Southern Illinois Coach Richard (Itchy) Jones. But, says Jones, “the scouts couldn’t know when he was going to pitch because we never did.” Mattick recalls having heard something about Stieb’s pitching, but he and LaMacchia were there to look at him strictly as an outfielder. Disappointed by what they had seen, they nevertheless decided to stay around long enough to see him throw. It was, Mattick concludes in retrospect, one of the smartest things he has ever done, no small claim for a man who signed the likes of Frank Robinson and Vada Pinson. “Stieb knocked our eyeballs out,” says Mattick. “He was absolutely overpowering. We hadn’t liked him as a hitter, but he sure as hell opened our eyes when he started pitching. We decided to draft him.”

In LaMacchia’s version of the story, as told in the Tampa Tribune in 1997, Stieb retired all seven batters he faced while throwing a 96-97 mph fastball and an 89 mph slider, the latter of which had been taught to him by pitching coach (and future Yankees executive) Mark Newman. To throw the scouts around him off the scent, LaMacchia vocally dismissed the hard-thrower to the six other scouts around him, saying, “These guys are all alike. They won’t be able to lift their arms the next day. Come back later and they’ll get rocked.” The decoy worked, and the Blue Jays were able to draft him, signing him for a $28,000 bonus.

Stieb hit just .192/.257/.253 with one homer in 110 plate appearances at A-level Dunedin in 1979 but had some success in four pitching appearances. Only when the Blue Jays — a 1977 expansion team that quickly produced some good outfielders but took longer to develop quality pitchers — told him that the fastest past to the majors was via the mound did he fully commit. Once he did, he rode a rocket, totaling just 128 minor league innings at Dunedin and Triple-A Syracuse before debuting on June 29, 1979.

Stieb quickly emerged as a very good pitcher on some pretty bad teams, making the first two of his seven All-Star appearances in 1980 and ’81 as the Blue Jays posted a .388 winning percentage in those years. While his fastball speeds — 92–95 or 96 mph, by his recollection — were above average, his biggest strength was a six-pitch arsenal (including a four-seamer, sinker and two curves thrown from different arm angles at different speeds), all of which he could throw for strikes. He wasn’t afraid to throw his fastball high and tight, leading the league in hit batsmen five times. His slider was his best pitch, good for inducing a lot of weak contact; his .260 BABIP was the second-lowest among all pitchers with at least 2,500 innings for the 1979–98 span. While his strikeout and walk rates were more or less average (102 K%+ and 100 BB%+ for his career), he was very good at suppressing home runs (78 HR/9+) despite being a flyball-oriented pitcher.

Stieb only led the AL in one triple crown category — his 2.48 ERA in 1986 — but ranked among the top five in ERA five times. Thanks in part to some big innings totals (an average of 275 from ’82 to ’85), he led the league in WAR three straight seasons and was in the top three for five straight (’81–85). In the last of those years, he helped the Blue Jays to their first playoff berth, and they came within one win of a trip to the World Series, though he was cuffed for six runs by the Royals in Game 7 of the 1985 ALCS, his third start of the series and his second in a row on three days of rest. But for as good as Stieb was during that ’81–85 run, he never finished higher than fourth in the Cy Young voting, and twice finished seventh, because he topped out at 17 wins due to meager run support and didn’t have the black ink in his favor.

His demeanor may not have helped. As John Lott described him in 1998:

“Stieb was a magnificent pitcher, a tragic hero, a lone wolf whose intensity could be as intimidating as his slider, a surly sort who alienated many a writer and some teammates as well … He hated to give in to a batter or a writer. For reasons that seemed irrational, he was sometimes as fierce off the field as on the mound, still fighting when the real fight was over.”

Bone chips in his elbow and tendinitis in his shoulder slowed Stieb down after that mid-1980s run, and his September struggles played a role in the team coughing up a playoff spot to the Tigers in 1987. He was back on his game from ’88 to ’90, earning All-Star honors in the bookend seasons and helping the Blue Jays to a division title in the middle one but having some absurdly hard luck when it came to his no-hit bids. In back-to-back starts on September 24 and 30, 1988, he came within one strike of a no-hitter, only to yield hits. On August 4, 1989, he came within one out of a perfect game, only to have it broken up; he gave up a run in that one, but had five one-hit shutouts in the 1988–89 seasons. Finally, on September 2, 1990, he pitched the first (and to date only) no-hitter in Blue Jays history, beating Cleveland.

Unfortunately, shoulder and back problems, including a herniated disc, prevented Stieb from ever making more than 14 starts in a season after 1990, his age-32 season. He was too injured to be a factor in the Blue Jays’ World Series-winning season in 1992 and reached free agency for the first time that fall. After a four-start stint with the White Sox in 1993 (his age-35 season) and a brief spell with the Royals’ Triple-A Omaha affiliate later that season, he walked away from the game. Four years later, he attempted a brief comeback with the Blue Jays in 1998, one that evolved out of his coming to Dunedin as a spring instructor. That he made it back at age 40 was a triumph; even if the numbers were nothing special, the experience gave him closure, allowing him to exit the game on his own terms.

Stieb was the best pitcher in the game for about half a decade, but his counting stats never gave him much chance with Hall of Fame voters; he drew just 1.4% on the 2004 ballot. Had he not gotten such poor run support (94.6% of the park-adjusted league average, based on a study I did at Baseball Prospectus with Colin Wyers, with Morris at a gaudy 107.1%), he probably would have lucked into 20 wins and a Cy Young award at some point during his peak and might have gotten to 200 wins and at least lingered on the ballot.

The advanced stats make a stronger case. Even with a career that fell short of 3,000 innings, Stieb ranks third in WAR among pitchers born during the 1950s, well behind Blyleven (94.5) but just 0.7 behind Tanana, who threw nearly 1,300 more innings, and 12.9 WAR ahead of Morris, who thew over 900 more innings. He has the highest ERA+ of any pitcher in that cohort, with Blyleven and Guidry the only others with at least 2,000 innings and an ERA+ higher than 112.

Though Stieb doesn’t make a huge jump in the move from JAWS (where he’s 73rd) to S-JAWS (63rd), he particularly pops as a member of this group. Hershiser’s offense (4.7 WAR) helps him draw to more or less even with Stieb in overall value, but the former’s adjusted peak and S-JAWS don’t make quite as strong a case. Though the two are 1.6 points apart in the latter, Hershiser is 13 spots lower in the rankings (76th), right in the midst of a huge pileup that I think constitutes an identifiable borderline.

Of the 15 non-Negro Leagues pitchers with 53–57 S-JAWS, 10 are enshrined. Four of the others I highlighted in the previous installment (Reuschel, McCormick, Ferrell, and Tiant), and the fifth — spoiler alert — is Kevin Brown, whose case awaits in my next installment. Of the 15 pitchers with 49–53 S-JAWS besides Clark Griffith, who was elected to the Hall as an executive, nine are enshrined. Stieb, Urban Shocker, and Tony Mullane are three of the outsiders we’ve already met; CC Sabathia awaits his turn on the writers’ ballot; and then there are two pitchers born in the 1960s, Kevin Appier and Chuck Finley.

From 46.8 to 49 S-JAWS — a very narrow but crowded band — just five out of 20 pitchers are enshrined: 300-game winners Mickey Welch and Early Wynn, dead-ball era stars (and all-time nicknames) Three-Finger Brown and Iron Man McGinnity, and Red Faber, a Charles Comiskey favorite who spent his entire career with the White Sox but missed the 1919 debacle due to illness. That leaves 12 others besides his now-banned teammate Eddie Cicotte and the still (technically) active Cole Hamels. Buehrle, Pettitte, and Tim Hudson were all on this year’s BBWAA ballot (Hudson fell off); John and Bob Caruthers were featured in the last installment, as I breezed past Bond, Charlie Buffinton, and George Uhle, older pitchers whom I found less compelling. That leaves Hershiser, two 1960s guys, and — another spoiler alert — Johan Santana, who was born in 1979.

I think it’s safe to say that last group is the fringe, where electing all of those pitchers isn’t practical or desirable but where some stand out more than others due to more subjectively weighted considerations, including awards, postseason work, and historical importance. Part of that last category comes down to a player’s standing within their era, and as I’ve evaluated the data over the course of this series, it’s become more apparent that some consideration — more than I had previously granted it, for certain — should be given to their standing within their cohort, which isn’t an exact overlap. In light of what feels like an acceleration of the forces that continue to reshape the role of the starting pitcher, both of those factors carry ramifications on how we’ll look at future candidates, and should reshape our view on the ones that have in the recent past. It’s not too late to honor them.

Thus, while I don’t think S-JAWS suggests either Stieb or Hershiser are exceptionally strong candidates, they stand as the best pitchers from an very underrepresented era of pitchers, scoring pretty well by this methodology and with other favorable credentials as well. I’ve always regarded both with great respect and affection while stopping short of outright advocacy for their election, but in light of this research, I’m much more comfortable getting behind their candidacies than before. It’s not just that they’re slightly better than Morris — they’re miles better, with careers that fit well within the range of many Hall of Fame starters whose places in Cooperstown don’t keep us lying awake at night.

But while they were born less than 14 months apart, their electoral paths won’t cross. Stieb, whose biggest impact on the game came before 1987, belongs to the Modern Baseball group, which will next be considered for 2024 induction, and just as Hallheads like myself kept a vigil for Lou Whitaker and Dwight Evans to join that ballot, so too for him. Hershiser, whose biggest impact came after 1987 — immediately after — belongs to the Today’s Game group, which will be considered later this year for induction next summer. This is not to suggest that either must jump to head of the line among their respective groups of candidates, but their cases deserve continued airing, and ultimately, they deserve election.

Brooklyn-based Jay Jaffe is a senior writer for FanGraphs, the author of The Cooperstown Casebook (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017) and the creator of the JAWS (Jaffe WAR Score) metric for Hall of Fame analysis. He founded the Futility Infielder website (2001), was a columnist for Baseball Prospectus (2005-2012) and a contributing writer for Sports Illustrated (2012-2018). He has been a recurring guest on MLB Network and a member of the BBWAA since 2011, and a Hall of Fame voter since 2021. Follow him on BlueSky @jayjaffe.bsky.social.

I was regularly playing a fantasy baseball like game (before it was a thing) and watching baseball all throughout the 80s. I think of Blyleven, Hershiser, Guidry, El Presidenti (Martinez), Saberhagen and Steib as the best of that decade. Tanana was hall of very good in my mind. As was Tudor! Gooden was the best pitcher but for too short a time. But those others all have strong cases to me. Hershiser’s streak alone was fame worthy! Guidry, Dennis Martinez, and Hershiser should have been shoo ins.

I guess Steib should get more credit from me based on his above numbers!

Saberhagen in 1989 was noteworthy. I was a fortune off him that year!

Another point in Hershiser’s favor: as the great Roger Angell once noted, he is the only player to have consecutive possessive pronouns in his surname.