Craig Kimbrel Is Dominant Once Again

At 4-6, with losses in two straight series, the Cubs are off to a sluggish start, but one player who has impressed thus far has been closer Craig Kimbrel. After struggling for the better part of his first two seasons in the Windy City, he has not only demonstrated dominant form in the early going, he’s actually built upon a rebound that began in the middle of last season, one that suggests his recovery is no passing matter.

Kimbrel, who last pitched on April 8, when he recorded a five-out save against the Pirates — his first outing of more than three outs since Game 3 of the 2018 World Series — has retired all 14 batters he’s faced this season, nine via strikeouts, including the first five batters he faced in the new year. What’s more, he’s retired 24 in a row dating back to last September 12, and 35 out of 38 going back to the start of last September, 22 (57.8%) via strikeouts. In that span, he hasn’t walked a single hitter or given up an extra-base hit, meaning that he’s held batters to an .079/.079/.079 line, an 83.0 mph average exit velocity, just one hard-hit ball (95.0 mph or greater), and not a single barrel. That’ll do.

In other words, Craig Kimbrel is back.

Once the game’s most dominant closer, Kimbrel made seven All-Star teams while pitching to a 1.91 ERA and 1.96 FIP with a 41.6% strikeout rate from 2010-18, making seven All-Star teams along the way. He wasn’t as dominant in his time with the Padres (2015) or Red Sox (2016-18) as he’d been with the Braves, but he did help Boston win a World Series in the last of those seasons.

Though he saved 42 games in 2018, his highest total since being traded by the Braves, Kimbrel set career highs in home run rate (1.01 per nine) and FIP (3.13) that season, and then was scored upon in his first four postseason appearances — apparently because he was tipping his pitches — before righting the ship.

Kimbrel became free agent after the 2018 season, and the Red Sox made him a qualifying offer. While a reunion seemed like a no-brainer given Boston’s lack of apparent alternatives, he was rumored to be seeking a six-year deal north of $100 million. The Red Sox, grinding up against significant penalties via the Competitive Balance Tax system, decided instead to go into cost-cutting mode, while Kimbrel couldn’t find a long-term deal to his liking. Ultimately, he waited until June 7, once the 2019 amateur draft had occurred and the draft-pick compensation attached to his rejection of the qualifying offer no longer applied, to ink a three-year, $43 million contract with the Cubs.

The returns on that investment have been less than stellar. The late-arriving Kimbrel made 23 appearances totaling 20.2 innings in 2019, the first on June 27, and while he notched 13 saves, he was lit for a 6.53 ERA and 8.00 FIP; bouts of inflammation in his right knee and his right elbow, both of which sent him to the Injured List, may have been factors. In the pandemic shortened 2020 season, he appeared to pick up where he left off, but not in a good way; in his season debut, he walked four out of six batters he faced, threw a wild pitch, and hit a batter. He allowed runs in each of his first four outings, and spent the entire season with an unsightly ERA, finishing with a 5.29 mark, a 3.97 FIP, and just two saves in 15.1 innings. His Statcast numbers, including a 91.1 mph average exit velocity, 18.5% barrel rate, and 51.9% hard-hit rate, were about as bad as they’d been the year before.

Lost amid those unsightly seasonal numbers was that Kimbrel was scored upon in just one of his final 14 appearance and gave up hits in just three of those outings; over that span, batters hit .098/.245/.098 while striking out 53.1% of the time. He’s carried that run into the new season, with four perfect outings and a 64.3% strikeout rate. In last Thursday’s game against the Pirates, he entered with the bases loaded and one out in the eighth, struck out both Dustin Fowler and Wilmer Difo — not exactly Ruth and Gehrig, admittedly — on four pitches apiece, and then pitched a 1-2-3 ninth for the five-out save.

So what happened? Underlying Kimbrel’s decline were some mechanical problems, and having a normal spring training to work them out, something he didn’t get in either of the past two seasons, was key. Via The Athletic’s Sahadev Sharma in mid-March, when he was again struggling:

Last season, the Cubs identified that Kimbrel was getting too rotational and was flying open early. This led to multiple issues, all connected in various ways: his arm slot dropped, he was pulling his fastball, his velocity was dipping and he had no control of his breaking ball. That the issues appear to be the same can give the Cubs a slight bit of comfort since they’ve gone through what appears to be a similar process before. They know the work that’s needed to get him back to where he was at the end of last season as he looks to sync up his body once again and get his mechanics right.

Kimbrel has been particularly focused upon maintaining his arm slot and release point, and has benefited from the Cubs’ high-tech pitching infrastructure. From a February piece by Sharma:

“What’s nice with the technology nowadays is that not everything is all feel,” Kimbrel said. “A lot of times in the past it was about trying to find the feel, and once we find the feel, everything else will come. But now we have the technology that’ll tell us that that pitch did what we wanted it to do. Even if it might not have felt well, that’s where you need to be. Because our bodies can trick us over time. Our arm can drop a little bit and it might feel great. But a hitter can see it better or you’re not spinning it as well.”

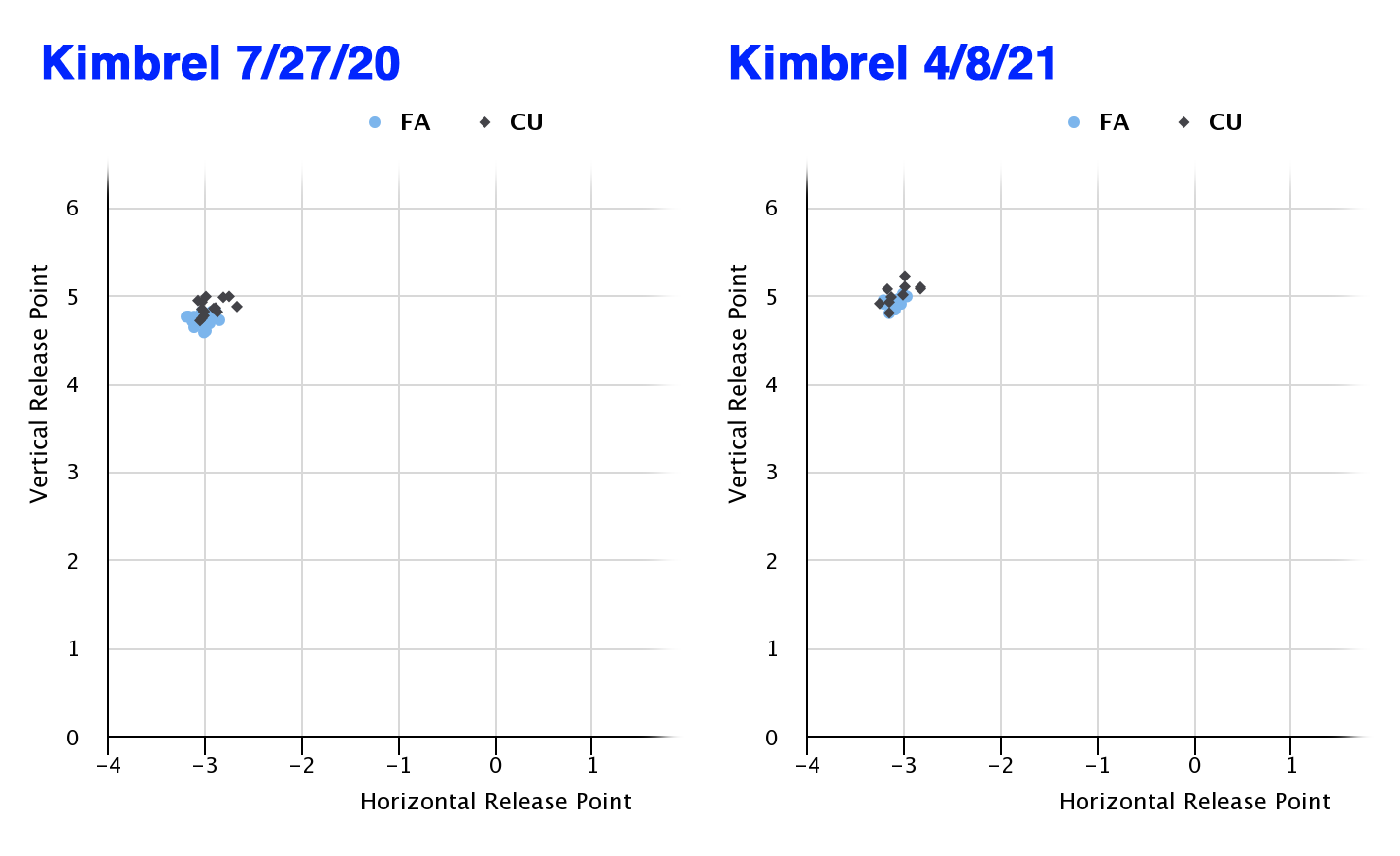

We can visualize the issues that were causing Kimbrel problems in a few different ways. Here’s a comparison between his release points from that debacle of a 2020 debut and last Thursday’s five-out save:

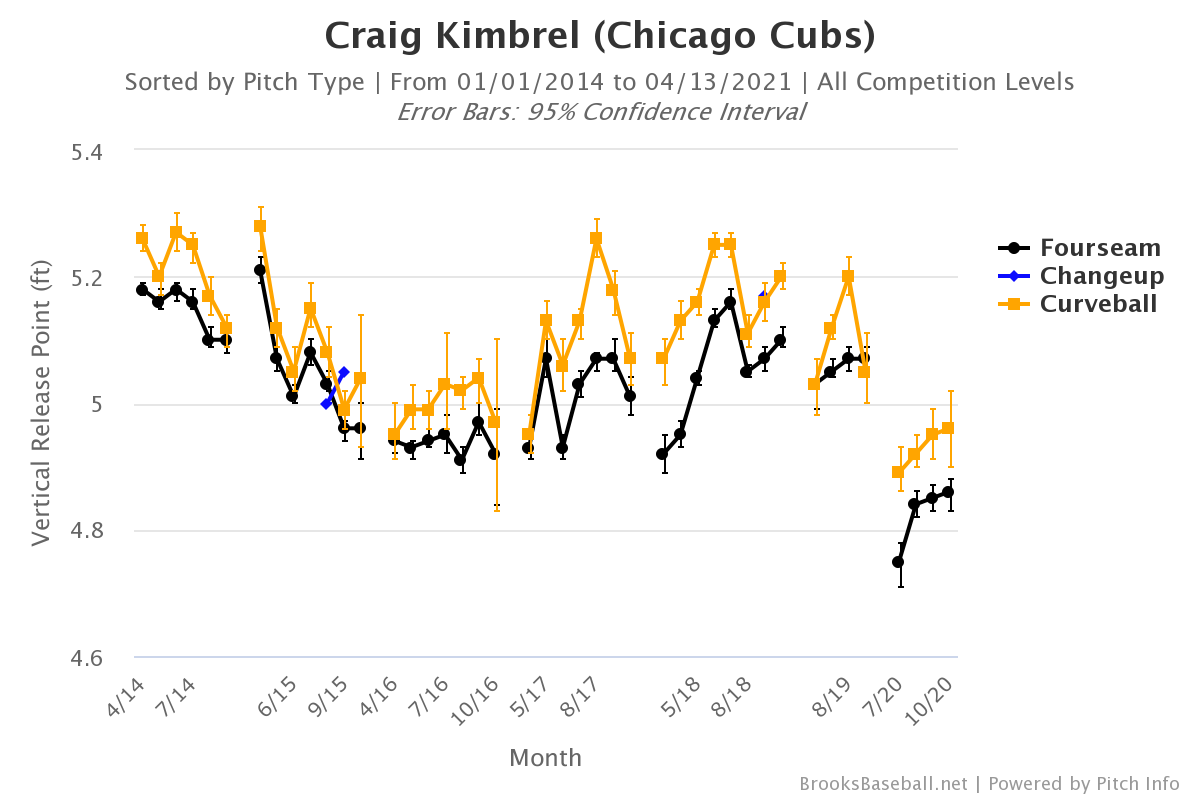

It’s not a huge difference, maybe a quarter-inch lower in the earlier game, but obviously, the results were night and day. Here’s a Brooks Baseball month-by-month comparison of Kimbrel’s vertical release points going back to part of his prime:

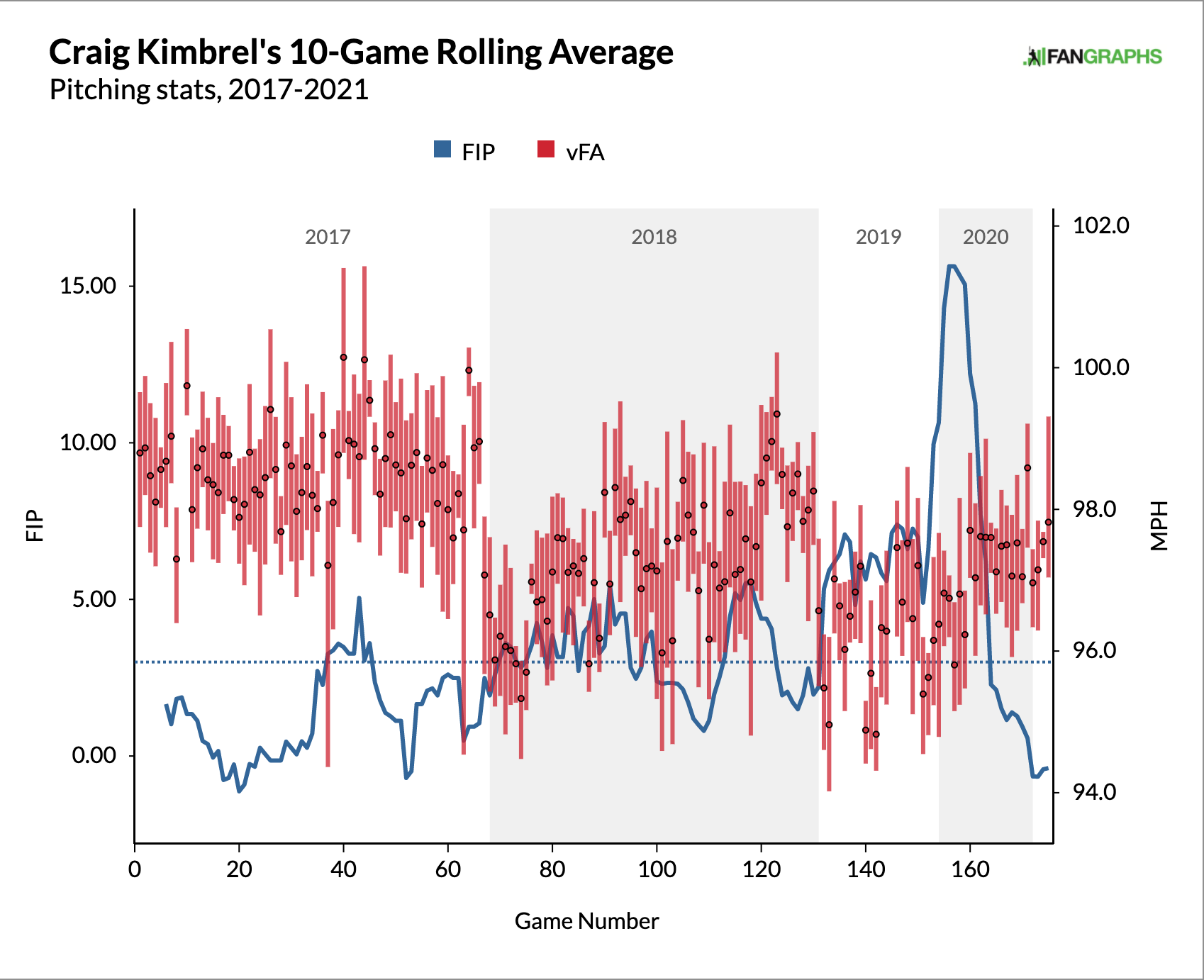

As you can see, his arm slot has fallen over the years, but he adjusted it after the rough early going last year; unfortunately, the 2021 data has not made it onto the visuals yet. And here’s a look at Kimbrel’s rolling average fastball velocity along with his rolling FIP:

All of those are based upon Pitch Info’s data, which can vary slightly from Statcast; per the former, Kimbrel averaged 98.5 mph with his four-seamer in 2017, but dipped to 97.2 mph in ’18, then 96.3 in ’19; he was back up to 97.1 mph last year and 97.4 thus far this year. Looking at the splits by Statcast a bit differently, he averaged 96.2 mph from the start of his Cubs carer through those first four outings in 2020, after which he didn’t pitch for a week, and is up to 97.0 mph since returning to action on August 14, 2020.

Via MLB.com’s Jordan Bastian, these Statcast heatmaps illustrate the better job Kimbrel is doing when it comes to keeping both his fastball and his curve out of the middle of the strike zone:

https://twitter.com/MLBastian/status/1380559588672540680

https://twitter.com/MLBastian/status/1380558743289626624

In addition to better location, Kimbrel’s latter-day fastball has a bit more horizontal movement on it, and the difference has been stark as far as xwOBA from those pitches is concerned: .538 in 58 at-bats ending with the fastball through early 2020, .117 in 29 at-bats starting with that August 14 outing. While there’s been very little change from the earlier stretch to the later in terms of his curveball (.251 xwOBA in 34 at-bats ending with the curve before, .235 in 26 at-bats after), his pattern of usage has changed. As MLB.com’s Mike Petriello noted, he’s been using the curve — his only other pitch besides the fastball — as his first pitch on half the batters he’s faced — he’s been in the 42-45% range in three of the past four seasons but never higher — and is pitching from behind in the count less often than at any time since he was a rookie in 2010.

So, Kimbrel appears to be right again, aware of what he needs to do to maintain his form and hold down the closer’s job, and potentially back on the path to Cooperstown. Last Thursday’s save was the 350th of his career, good for 12th on the all-time list; Troy Percival (358 saves), Jeff Reardon (367, briefly the all-time high), Jonathan Papelbon (368) and Joe Nathan (377) are all within reach with a normal workload this year, and Dennis Eckersley (390) isn’t too far off; passing the last of those would mean climbing into seventh place on the all-time list.

Meanwhile, Kimbrel has climbed from 22nd to 20th in the WAR-WPA-WPA/LI hybrid stat I’ve been using to measure reliever Hall-worthiness in place of JAWS in recent years, having leapfrogged the lowest-ranked of the eight enshrined relievers:

| Rk | Pitcher | WAR | WPA | WPA/LI | Avg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mariano Rivera+ | 56.3 | 56.6 | 33.6 | 48.8 |

| 2 | Dennis Eckersley+ | 62.1 | 30.8 | 25.8 | 39.6 |

| 3 | Hoyt Wilhelm+ | 46.8 | 30.5 | 26.5 | 34.6 |

| 4 | Rich Gossage+ | 41.1 | 32.5 | 14.8 | 29.5 |

| 5 | Trevor Hoffman+ | 28.0 | 34.2 | 19.3 | 27.2 |

| 6 | Billy Wagner | 27.7 | 29.1 | 17.9 | 24.9 |

| 7 | Firpo Marberry | 30.3 | 26.3 | 17.3 | 24.6 |

| 8 | Joe Nathan | 26.7 | 30.6 | 15.8 | 24.4 |

| 9 | Tom Gordon | 35.0 | 21.3 | 14.5 | 23.6 |

| 10 | Jonathan Papelbon | 23.3 | 28.3 | 13.4 | 21.7 |

| 11 | Ellis Kinder | 28.9 | 23.6 | 11.7 | 21.4 |

| 12 | Francisco Rodriguez | 24.1 | 24.4 | 14.7 | 21.1 |

| 13 | Lee Smith+ | 28.9 | 21.3 | 12.7 | 21.0 |

| 14 | Stu Miller | 27.0 | 20.2 | 12.9 | 20.0 |

| 15 | Tom Henke | 22.9 | 21.3 | 13.9 | 19.4 |

| 16 | Dan Quisenberry | 24.6 | 20.7 | 12.5 | 19.2 |

| 17 | Rollie Fingers+ | 25.6 | 16.2 | 15.1 | 19.0 |

| 18 | Tug McGraw | 21.8 | 21.5 | 13.1 | 18.8 |

| 19 | Bobby Shantz | 34.7 | 10.4 | 10.3 | 18.5 |

| 20 | Craig Kimbrel | 19.8 | 23.2 | 12.1 | 18.4 |

| 21 | John Hiller | 30.4 | 14.6 | 9.4 | 18.1 |

| 22 | Bruce Sutter+ | 24.0 | 18.2 | 11.9 | 18.0 |

| 23 | Kent Tekulve | 25.5 | 14.2 | 13.9 | 17.9 |

| Hall avg w/Eck | 39.1 | 30.0 | 20.0 | 29.7 | |

| Hall avg w/o Eck | 35.8 | 29.9 | 19.1 | 28.3 |

I said that Kimbrel has climbed, but in actuality, he’s reclaimed lost ground; through 2018, he scored 18.9 in this metric, but back-to-back seasons with sub-zero WARs and WPAs knocked him down a few pegs. Obviously, he’s still a ways off from cracking the top 10, where things start to get interesting; Wagner, the highest-ranked reliever outside the Hall by this metric, and sixth in saves (422), is gaining significant traction, with 46.4% of the vote in the 2021 election, while Nathan, who’s eighth both here and in saves, will be on the upcoming ballot.

More immediately, the question is how long Kimbrel will remain a Cub if he continues to pitch well. Despite finishing first in the NL Central last year with a 34-26 record, the team began dismantling its roster by trading Yu Darvish, letting Jon Lester, Jose Quintana, and Tyler Chatwood (among others) depart in free agency, and non-tendering Kyle Schwarber. Kris Bryant, Javier Báez, Anthony Rizzo, and Zach Davies, the last of whom was part of the Darvish return, will be free agents this winter. The Cubs could look very different at this time next season.

Kimbrel will be a free agent after this season, too, barring the Cubs picking up his $16 million option, which has a $1 million buyout ($2 million if he finishes at least 53 games this year). While the NL Central may be a race to 85 wins or so, the Cubs may well be sellers at the trade deadline, and Kimbrel, who had some amount of no-trade protection in the first two years of his deal, no longer has any.

All of that remains to be seen, as does whether Kimbrel maintains his utterly stifling performance. But now that he’s found himself as a Cub, and figured out what caused his decline, he’s a force to be reckoned with once again.

Brooklyn-based Jay Jaffe is a senior writer for FanGraphs, the author of The Cooperstown Casebook (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017) and the creator of the JAWS (Jaffe WAR Score) metric for Hall of Fame analysis. He founded the Futility Infielder website (2001), was a columnist for Baseball Prospectus (2005-2012) and a contributing writer for Sports Illustrated (2012-2018). He has been a recurring guest on MLB Network and a member of the BBWAA since 2011, and a Hall of Fame voter since 2021. Follow him on BlueSky @jayjaffe.bsky.social.

I doubt either catch Rivera in the ranking of closer greatness (he was so good for so long) but I think Kimbrel and Chapman will be right there with Wagner vying for the distinction of second greatest closer of all time.