Dodgers Sign Alex Wood, Human Lottery Ticket

On July 5, in his last start before the All-Star game, Alex Wood was dealing. The Diamondbacks couldn’t touch him with a thirty-nine-and-a-half foot pole. Over seven dominant innings, he struck out 10 batters, walking only two in a scoreless outing. Wood didn’t start the All-Star game, but he could have; his 2.04 FIP, 30.9% strikeout rate, 1.67 ERA, and 10-0 record had something for every stripe of fan. As he walked off the mound, the crowd at Chavez Ravine roared.

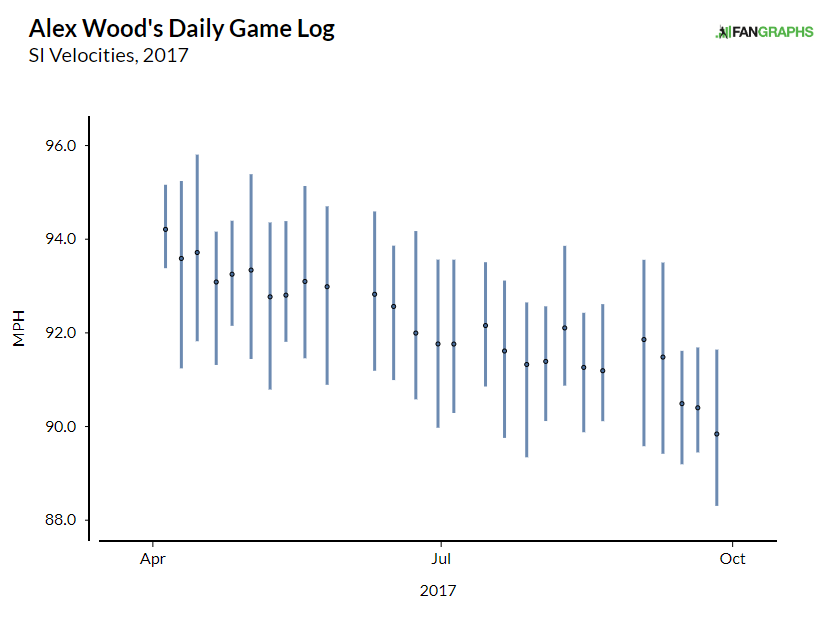

Wait — Chavez Ravine? Oh. Yeah. I left something out. That was July 5, 2017. It’s been a minute since Alex Wood was at his world-devouring best. In the second half of that season, he was ordinary, potentially sub-ordinary. His strikeout rate fell 12 points, his FIP more than doubled, and the Dodgers started managing his workload. The culprit? It can often be hard to pin one down, but in this case, well:

Not what you like to see. The Dodgers skipped his spot in the rotation once, hoping he’d recover, but never put him on the IL. He averaged 90.4 mph on his fastball in the playoffs, and while he was mostly effective, the early-season magic never came back.

It’s been a long time since that dominant first half. Wood’s path has been tortuous, and at times torturous. 2018 was another effective season, less electric but still solid. Wood’s two best attributes, his groundball rate and control, kept his value high, even as his strikeout rate never quite rebounded to his 2017 peak. In an attempt to bottle that lightning just one more time, the Dodgers moved Wood to the bullpen for September and the playoffs, and while his velocity ticked up, so did his home run and walk rates.

And just like that, he was gone. The Dodgers shipped him off to Cincinnati along with Yasiel Puig in a bid to drop their payroll below the luxury tax. In Ohio, Wood had a nightmare season; a lingering back injury limited him to seven bumpy starts. He allowed 11 homers in 35.2 innings, which is, for those of you keeping count at home, bad.

Of course, we’re not here to rehash the last three years of Wood’s career. On Sunday, the Dodgers signed Wood to an incentive-laden contract that will pay him between $4 million and $10 million in 2020. For the Dodgers, it’s another bite at the positive regression apple; Wood joins Jimmy Nelson and Blake Treinen as intermittently spectacular pitchers LA hopes to rehabilitate. For Wood, it’s a chance to return to the team for which he’s been most effective, and a short contract that will let him dip back into the market next year if things work out.

Of course, “if things work out” is doing a lot of work in that last paragraph, from both Wood’s and the Dodgers’ perspective. Walk up to a Dodgers fan and tell them they signed a pitcher with a sub-2.00 ERA, and they’d be ecstatic. Add, “in the first half of 2017, oh and also, it’s Alex Wood,” and they’d be understandably annoyed with you.

Dreaming on Wood is easy, because we know he’s done it before. That led me to a question: what can the Dodgers do to bring back the Alex Wood who turned the NL West into a joke show in the first half of 2017?

First, there’s the velocity. That’s a tough one to bring back, but it’s not impossible. Wood is sneakily young; he’ll pitch all of next year at 30, and pitchers break rather than aging in general, so it’s reasonable to expect some rebound in velocity if he’s healthy in 2020.

And if Wood regains that velocity, there’s good reason to believe he’ll regain the swing and miss element of his game that so thoroughly deserted him in 2018. In the first half of 2017, Wood ran a 13.6% swinging strike rate. That’s not elite, but adding that element to his core strengths of limiting walks and keeping the ball on the ground snowballed.

That swinging strike rate wasn’t sorcery. It was driven by batters swinging through his sinker. Batters whiffed on 22.6% of their swings at the pitch over the first half of 2017. That might not sound like much, but among starters who threw at least 500 sinkers in 2019, that would be the fourth-best mark in baseball. And those whiffs were driven strongly by velocity.

Consider this: since the beginning of 2015, batters have swung at 309 of his sinkers thrown 92 mph or harder. They’ve whiffed on 19.4% of them, which compares favorably to Noah Syndergaard’s whiff rate on his two-seamer in 2019. They’ve swung at 374 sinkers thrown between 91 and 92 mph, whiffing on 15.8%. Below 91 mph (1219 sinkers), they’ve come up empty only 13.6% of the time. That’s a statistically significant difference, and it makes sense: throw harder, miss bats.

You can find other reasons Wood was so effective if you’re willing to grasp at straws. For example: in that first half of 2017, Wood mixed his pitches with panache. When he threw a batter a changeup to start, his next pitch to that batter was roughly half fastballs, one quarter curves, and one quarter changeups. It was roughly the same when he threw a fastball — 40% fastballs, 30% changeups, 30% curves. On his curveball, you guessed it: 50% fastballs, 30% changeups, and 20% curves.

The point is, he was hard to pin down. Batters couldn’t do much better than guess at what was coming. In 2018 and 2019, that sheer unpredictability has gone away. When Wood throws a changeup, he most often follows it with another changeup (40%). He almost never followed a fastball with another fastball (16%), and was at his most unpredictable after a curve. It’s not that Wood was following an exact pattern; he just became easier to read.

This is, of course, rank speculation. It could easily be something else. It could easily be that Wood didn’t deserve the strikeout rate he posted in the first half of 2017. He might have lost mastery of his pitches in a way that he can’t fix. From the outside looking in, we simply can’t know what might go right and wrong in 2020.

But luckily, we don’t have to know the future to consider LA’s calculus in making this deal. The Dodgers are in a unique position, so far atop their division that they almost don’t care about regular season wins and also so stacked with talent that an average pitcher won’t move the needle.

Steamer projects Wood to be just fine next year; a 4.09 ERA and 4.26 FIP, or 1.6 WAR over 128 innings. That seems like a great deal for the Dodgers, but when you take into consideration that it’s in a split role between starting and relieving, it becomes slightly less interesting. Add in the fact that the Dodgers are absolutely stacked when it comes to starting pitchers, and it’s even less interesting.

The Dodgers go nine deep in reasonably interesting starters:

| Pitcher | Proj ERA | Proj IP |

|---|---|---|

| Clayton Kershaw | 3.55 | 204 |

| Walker Buehler | 3.48 | 197 |

| Julio Urías | 4.03 | 141 |

| Kenta Maeda | 4.06 | 122 |

| Alex Wood | 4.09 | 122 |

| Dustin May | 4.08 | 94 |

| Ross Stripling | 3.72 | 38 |

| Jimmy Nelson | 4.24 | 28 |

| Tony Gonsolin | 4.73 | 18 |

And so Wood doesn’t hold a lot of interest as an average player. Take out his average innings, and Dustin May or Ross Stripling or even Tony Gonsolin could fill in without much loss. No, the Dodgers are after upside.

Consider this theoretical distribution of Wood’s outcomes, with a mean ERA of 4.09:

| Odds | State | True Talent ERA |

|---|---|---|

| 15% | Great | 3 |

| 65% | Okay | 4.09 |

| 20% | Bad | 4.9 |

Don’t take these numbers as gospel, because I literally just made them up. But this is the bet the Dodgers are making with Wood. They don’t care if he falls in the okay or bad buckets; he’s not doing much for their team if he does. But if his true talent is on the high end of the scale, it’s wildly valuable for a team looking for impact starters for the playoffs.

Think of the math this way. If Wood is okay, let’s say he makes $6 million — the incentives aren’t yet known, but we’re working in ballpark figures here. If he’s bad, he makes $4 million. If he’s great, he makes all $10 million. In expectation, they’re paying him $6.2 million. In return for their money, they get nothing useful 85% of the time.

That’s not a perfect assumption, because Wood has value as an average pitcher. Even the deepest team gets something out of league average innings, because it saves wear and tear on other arms. But let’s call that nothing, because I want to show something else here.

If the 15% scenario pans out, the Dodgers get a dominant starter, one with a true-talent ERA more than a run lower than the person they’d run out in his stead. And that’s really valuable! If you assume Wood averages 5.5 innings per start, upgrading from average to great saves the team 0.67 runs per Alex Wood start. Take the Dodgers’ actual run scoring and prevention numbers from last year and modify them by Good Wood’s effect (replacing, let’s say, Julio Urías in the playoff rotation), and the Pythagorean expectation increases the Dodgers’ winning percentage in that game by 7 percentage points.

That’s a meaningful swing; get two Wood starts in a seven game series, and it starts to add up. If the Dodgers were exactly 50% to win a series before adding two starts worth of peak Alex Wood, they’d be 54.3% to win the series with him in the fold. That’s roughly the equivalent of adding an impact bat, someone who increases the team’s scoring by 0.2 runs per game. Using extreme back-of-the-envelope math, that’s a 5 WAR position player, give or take.

So the Dodgers aren’t signing Alex Wood and seeing what happens; not exactly, at least. They’re buying a lottery ticket; a lot of the time, Wood will be of little value to them. Rarely, however, they’ll win big; Wood will recapture his 2017 form, and the team will have a great starting pitcher for the playoffs. A dominant playoff starter should cost more than $6.2 million, and mostly shouldn’t be available. But if you’re willing to take zeroes a lot of the time, you can make moves like this, spending money for a chance at something wondrous.

There are other benefits there as well. As a lefty, Wood has a fallback of being a useful bullpen arm. If he’s a 3.50 true talent ERA pitcher, that’s still valuable. And honestly, my percentages are arbitrary. They could be way off. The point is that the Dodgers are the perfect team to assume a variable return like this. Alex Wood might be terrible in 2020. But for the Dodgers, that’s fine. He might be great, too!

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

On Craig’s article last week about the linearity of the value of war, I tried to talk about this concept a bit. It might be most blatantly on display in how the Dodgers are interacting with Wood, or Jimmy Nelson, but for most signings of players who project at 1 or less WAR (especially pitchers), this is what’s going on: the team isn’t interested in the median outcome, they are looking at the distributions of outlier outcomes and paying based on their expectations of the likelihood of hitting one of those outcomes. If they get a bad outcome, or even an average one, the player likely doesn’t get that much playing time.

If Alex Wood is his median projection, he won’t even get those 122 innings to find out. The Dodgers, as usual, have 10 starting pitchers, and the back 7 or so of them are mostly interchangable. Of those 7 guys, it will be the 3 or so who perform the best who get the innings. The ones who perform the worst may not even stick on the roster. The ones in the middle will fill out the bullpen.

This is where we would really benefit if ZIPS or Steamer shared a feature with BP’s PECOTA: published percentile outcomes, so you can see what the 10th and the 25th and the 75th and the 90th look like for each player. Those outcomes are highly relevant here.

The Dodgers may be somewhat unique in that they are making these kinds of transactions with people who project to be league average starting pitchers, but every team is making those kinds of probability transactions on the back of their roster, and we’re poorly equipped to analyze them without knowing what the shape of people’s outlier outcomes look like.

I do think that is something that is lost frequently in analysis. The analysis is often saying something about how X player is redundant on the roster, or they are blocking a prospect, etc, but I think the teams instead are looking at what could actually happen. To me a good example is Puig. When he inevitably signs somewhere and we look at his 1.8 WAR projection I’m sure said team will have a player with a very similar projection who Puig will start over. But that player isn’t as likely to have his ceiling. That is why teams trade for guys like Mazara. It is for the ceiling.

Well, except the difference is that with Wood you’re banking on a guy returning a previously established level if they can stay healthy, which was pretty high…as opposed to a guy who you’re hoping for a breakout. In the first scenario, if the guy isn’t healthy, they don’t play him and they can play someone else. In the second scenario, you have to give a guy a lot of playing time and expose yourself directly to the downside risk.

The injury factor does mean these are a bit easier to see in the case of pitchers, but this kind of calculus happens at the player level a lot, too. Dudes like Asdrubal Cabrera won’t get 500 PAs if they’re bad, either.

With position players it’s often ‘will he maintain his established level or experience a rapid age decline as is common in guys who are 34’. The established level is better than the projection, because there’s a 30% attrition rate built into said projection.

There’s also the part where the Dodgers know Wood pretty well, and so you gotta think you’re more likely to get the best out of him (because you did before and you have some internal info that guides you) or the worst (because he’s sadly broken), but probably not the middle?

The same kind of calculus is going on with Nelson and Treinen; the more interesting calculus is that Wood thinks that going to a team w/ very competitive playing time is better for him to recoup his value than signing an equivalent incentive-laden deal with a team in more desperate need of his help: this suggests he (and Nelson) think the Dodgers are more likely to be able to fix them than, say, the Angels or (insert other team that needs league-average pitching really bad)